Office, messaging and verbs

This is a still from the classic film 1960 'The Apartment'. Jack Lemmon plays CC Baxter, a clerk in a large insurance company in New York, and so here you see his office - drones laid out at desks almost as far at the eye can see. Each desk has a telephone, rolodex, typewriter and a large electro-mechanical calculating machine.

In some of the other shots you can see the manufacturer - 'Friden'.

In effect, every person on that floor is a cell in a spreadsheet. The floor is a worksheet and the building is an Excel file, with thousands of cells each containing a single person. CC Baxter is on the 19th floor, section W, desk 861. The links between cells are made up of a typewriter, carbon copies ('CC') and an internal mail system, and it takes days to refresh whenever someone on the top floor presses F9. (Shirley MacLaine plays an elevator attendant, so this is actually a romance between a button and a spreadsheet cell.)

When people talk about productivity - about PowerPoint and Excel and how Google Docs and the cloud will or won't kill them, or messaging and the cloud, or how you need a PC for 'real work' - I'm reminded of CC Baxter and his Friden calculating machine. What killed those machines was not better, cheaper competitors but a completely different way to address the same underlying business need. Instead of hundreds of people recalculating insurance rates, the company bought a mainframe. The business need was being met, but the mechanism changed completely and the old tools disappeared.

The way forward for productivity is probably not to take software applications and document models that were conceived and built in a non-networked age and put them into the cloud, or to make carbon copies of them as web apps. This is no different to using your PC to do the same things you used your typewriter for. And of course that is exactly how a lot of people used their PCs - to start with. Just as today we make web app copies of software models conceived for the floppy disk, so the first PCs were often used to type up memos that were then printed out and sent though internal mail. It took time for email to replace internal mail and even longer for people to stop emailing Word files as attachments. Equally, we went from typing expense forms (with carbon copies) to entering them into a Word doc version of the form, to a dedicated Windows app that looked just like the form, to a web page that looked just like the form - and then, suddenly, someone worked out that maybe you should just take a photo of the receipt. It takes time, but sooner or later we stop replicating the old methods with the new tools and find new methods to fit the new tools.

Hence, channeling Marshall McLuhan, new tools start out being made to fit the existing workflows, but over time the workflows change to fit the tools.

Some times and only sometimes, it's possible to see the new model springing into existence, like Athena fully formed. This 1979 preview of VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet software, captures just that. The writer has to explain, slowly, what the concept we call a spreadsheet is (the term itself is never used), and what it might be good for, because for most people there was no paper analogue.

(Almost as good as this review, incidentally, is the fact that the same page has a discussion of competing videotext services.)

Yet, very early, it became clear that though spreadsheets are indeed 'magic paper', they're often, indeed perhaps mostly, used for things that aren't actually calculations. As Joel Sposky pointed out here, Excel is a great way to make tables. It's also both the world's most widely deployed IDE and the world's most widely deployed desk-top publishing program. In Japan people used it instead of Word to write letters (for the layout control). I spoke on Twitter a while ago to a consultant who told me that half his jobs were telling people using Excel to switch to a database and the other half were telling people using a database to switch to Excel. The tools fit the workflow, and then the workflow fits the tools.

I'd suggest that Microsoft Office is actually somewhat unusual in the field of productivity apps in how broad its use ended up being. Most normal people don't use Photoshop just to crop their holiday pictures or AutoCAD to sketch out where to put a new sofa, but Office encompasses both people who are using it for what it's designed and optimised for, and people using it because it's there, since it's so widely and cheaply distributed (perhaps 1bn copies are in use today in one way or another) and so broad and flexible. (One could debate this, of course - using Photoshop to generate web layouts is arguably as 'abusive' as using Excel as a database.) So there are people using Excel to build complex financial models and people using it to manage timetables, people using Word to create complex structured documents and people using it to write memos, and people using Powerpoint to communicate complex data to wide audiences and people using it for internal metrics reporting.

For decades, this has prompted the idea that if most people don't need most of the features, a competitor, with fewer features but cheaper or with different routes to market, can peel away more and more of the users, leaving behind only the very core power users. This never really happened, and it seems to me that this may be the wrong way to think about the issue.

The power users need those features because it is their job to make complex financial models, sophisticated presentations or structured documents and so on, and those features help them do that. But the reason that all the other users can sometimes do without all the features is not because their job is to make simpler, more basic documents - rather, their job is not actually to make presentations or models at all. They're in sales or marketing or logistics or dozens of other roles and they're using these tools because that's what they have, but that's not their job - it's just a tool. So these people should not be using a simpler cheaper alternative to Powerpoint or Excel (or indeed Photoshop), or one with a few different features. Rather, the way they change tools is if you give them fundamentally different ways to achieve the underlying task.

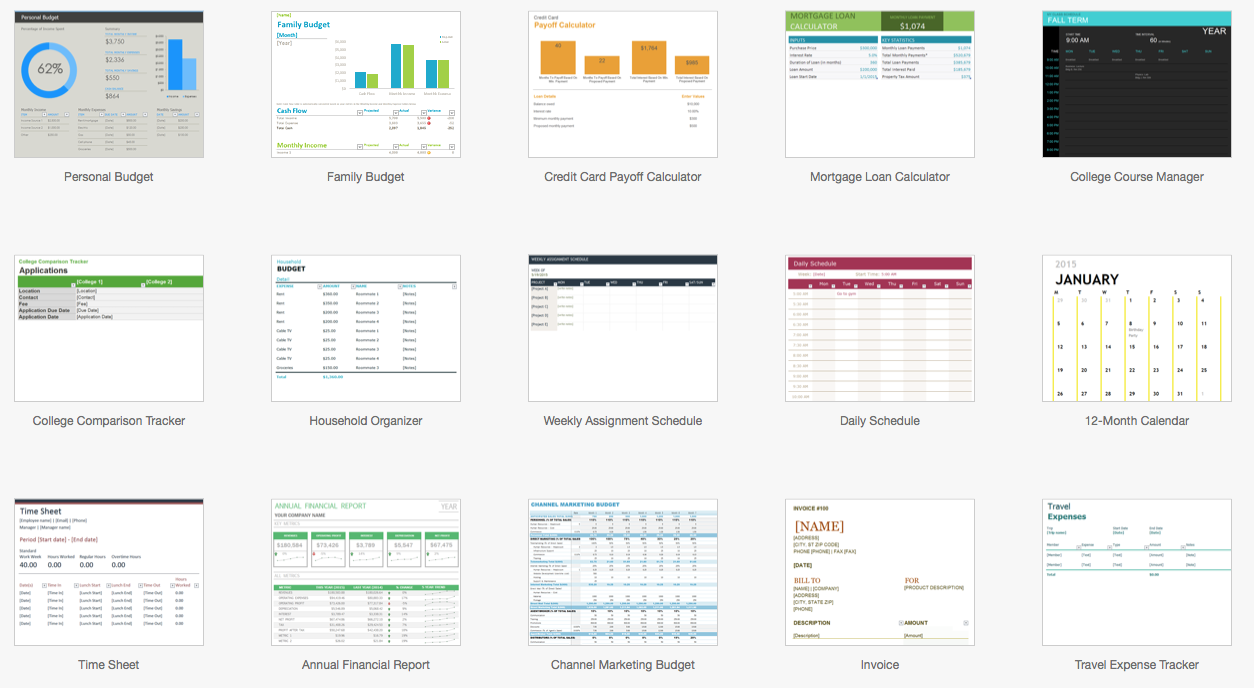

Hence today, in a thousand companies, a thousand execs will pull data from internal systems into Excel, make charts, put the charts into PowerPoint, write some bullets and email the PowerPoint to a dozen other people. What kills that task is not better or cheaper (or worse and free) spreadsheet or presentation software, but a completely different way to address the same underlying need - a different mechanism. That Powerpoint file could be replaced by a web app for making slides that lets two people work on it at once. But it should be replaced by a SaaS dashboard with realtime data, alerts for unexpected changes and a chat channel or Slack integration (Slack is an a16z investment). PowerPoint gets killed by things that aren't presentations at all. The business need is met, but the mechanism changes. You can see some of these use cases in the suggestions in the 'File/New' menu. Each of these is a smartphone app or a web service - the unbundling of productivity apps. And none of these have to be 'spreadsheets'.

What also changes, of course, are our assumptions about what hardware, precisely, you need. Do you need a large or small screen, do you need a keyboard, a mouse or just touch, and do you need a complex multi-window OS (Windows, Mac OS) or a simpler model based on full-screen use (Windows 8 et al, iOS, Android)? If you have to make an Excel file, paste charts into PowerPoint and write bullets or a memo then yes, keyboards, mice and windowing make things much easier. But if you have to flag a few key changes on a dashboard and tag them for review by three colleagues, you might not. The business task being achieved might be the same. Again - you need a keyboard to do x, but is x actually your job, or it it just the tool you use today to do your job?

Productivity breaks down into a set of verbs. In CC Baxter's office you see each of those verbs made into a physical object. Over time, those verbs get combined, broken apart, linked, created and removed as the tools change, the organization is changed by the tools and of course the underlying business itself changes. You don't actually send email or make a spreadsheet - you analyze, delegate, report, confer, decide, track and so on. Or, perhaps, 'what's going on, what are we doing and what should we be doing?' Each set of tools fixes that into a different pattern, but one should not look at that pattern and assume that that's the way things must be done - that that's what 'real work' looks like.

A thread through all of this is communication, which prompted the slide below (created in PowerPoint, of course). Communication changes from a typed memo hand-carried to your desk in a manila internal mail envelope, to a carefully-laid-out presentation laboriously crafted in PowerPoint (maybe emailed, maybe presented on screen, maybe printed), to threads in Slack, a chat app with third-party service and data integrations. The real, underlying task is to communicate around the problem "how are sales of widgets going, why, and what should we do about it?", and that might not have changed at all, though you might have gone from a week to a day to a minute to get the answer.

Distilling that further, there is information and the creation and analysis of it, and then there is communication - the connective tissue of the organisation. Right now, both of these generally mean the creation and the passing around or talking through of document files. But there's nothing eternal about that model.

Ironically, Lotus Notes, one of the earliest corporate messaging programs, was intended to be much more than email, calendaring and so on - there was a vision of a unified development environment, database and messaging system - 'groupware'. It didn't quite work out like that, and actually using Lotus Notes as I had to 15 years ago was rather like using an email client built with Microsoft Access - theoretically possible, and every clever, but not a good idea. OLE in the 1990s was another concept that didn't quite work; embedding pieces of one program's document inside another. But today, Facebook's platform on the desktop is pretty much Ray Ozzie's vision built all over again but for consumers instead of enterprise and for cat pictures instead of sales forecasts - a combination of messaging with embedded applications and many different data types and views for different tasks. Hence, one could propose one future model as 'Facebook for the enterprise', but with the platform, not the social, being the point of the analogy.

This is also what productivity concept videos, like this one from Microsoft, tend to look like. Somehow scifi interfaces never have multiple applications from different vendors with patchy cross-compatability. Rather, every different data type flows seamlessly between nodes and screens. Everything is structured data (no more typing numbers from a PDF into Excel) and everything is a message, or can be. This video is really showing Facebook, but for the enterprise and with lots of really thin sans-serifs.

The challenge here is the trade off between breadth and flexibility on one hand and focus and single-purpose efficiency on the other. It's easy to make everything flow together in a single UI if you have a narrow domain, but much harder if you're trying to encompass lots of different tasks and types of data. Sometimes the right 'unified UI' is a dedicated app and sometimes it's Windows, or a web browser, aggregating lots of different apps with different UIs. But mostly, it's the email app itself that's the universal connector, linking documents, data and ideas. That is, 'Send' is the universal verb that ties the others together.

There have been lots of experiments in this area besides Notes or Facebook - one could include Google's abortive Wave all the way back in 2010, Microsoft's Courier concept and now Microsoft's 'Gigjam' project. But a good place to see this now is to compare two productivity startups: Slack and Quip.

Slack is a person-to-person messaging platform that's more than messaging - through third-party integrations, it acts as a common aggregation layer for every other system in an enterprise. All the messages, updates and notifications from the dozens of other systems in a company can be inserted into the relevant team or project chat channels, and then be scanned through or searched later on. Slack is effectively a networked file manager, but instead of folders full of Photoshop, Word or Excel files you have links to Google Docs, SAP or Salesforce, all surrounded by the relevant context and team conversation. Then, if Slack is messaging that adds software, Quip is the other way around - productivity software (tables, analysis, text, tasks and so on) with messaging as an integral part of the data model, rather than siloed into a separate app ('email this document'). What both are trying to do is blur the boundaries between 'messaging' and 'applications' such that the data all sits within the communication space - rather like that Microsoft concept video above.

Much the same is happening in smartphone interfaces more generally, as I discussed here: the difference between messaging and apps is blurring. All of this recalls the old tech joke ('Zawinski's Law') that all software expands until it can read email, but now this works in both directions - messages become software, but software becomes messages.