AS COMPANIES LIKE Oculus, Valve, and Google address virtual reality’s technological hurdles, the interesting problems in VR no longer hinge on the question, “Can we do this?” Instead, for those working in the field, the question to ask—the one that will truly drive adoption—is “What can we do with this?”

It’s an exciting opportunity for those willing to step up and create brand new experiences. But just as the transition from still photography to film opened the door to a universe of new creative possibilities, the transition to VR requires a nearly complete re-imagining of the content creation process.

The Language of Virtual

Those of us who’ve spent the last few years trying out every piece of VR content that’s popped up across Oculus’s beta platform, Samsung Gear VR, and Google Cardboard can attest to the fact that what has worked in film and games in the past doesn’t translate directly to standout experiences in virtual reality.

Virtual reality is a new visual medium that will require ways of expressing information and narrative. Just as film required cuts, panning, and zooming, VR requires new ways of presenting a series of events in a way that is A) engaging and B) not nausea-inducing.

For now, the sheer immersion of VR gives creators some leeway. We’re in the phase equivalent to early film, when simply showing a train approaching the viewer was mind-blowing. Even with limited fields of view and (in the grand scheme of things) low resolutions available on today’s hardware, you’ll be hard-pressed to find anyone whose jaw doesn’t drop the first time they try a modern VR experience.

The current paradigm for non-game content is to drop users in the middle of a scene and give them few minutes of content to look at in every direction. This allows scenes to be short (which helps with the nausea some users face) and increases the odds that you’ll want to try an experience more than once (doubly important while there’s limited content available to early adopters).

In cinema, cuts, pans, and zooms let a director say “that is what matters in this scene.” We still don’t know what will enable this in virtual reality. Will it be faint visual cues highlighting characters or details in the scene transpiring around the user? Or is a more heavy-handed approach required, perhaps selectively limiting a user’s ability to look around?

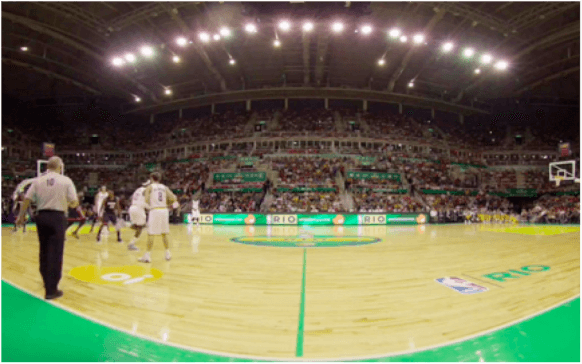

The NBA experience for Gear VR gives users a court-side seat, but keeps attention focused on the game by limiting their ability to turn completely around. NEXTVR

Answering these questions goes hand-in-hand with creating the first killer apps in virtual reality. As Beau Cronin pointed out in a recent Medium post, “it’s not just the raw technical capabilities that determine whether a given use for VR is ready for prime time; it’s also the collective knowledge of the product development community about how to use these tools to the greatest possible effect.”

Technical Constraints

While Moore’s Law is on developers’ side, it’s still important to consider the technical limitations of devices that will be providing VR experiences for the next few years.

Rendering a scene in virtual reality requires far more hardware resources than the exact same scene on a traditional screen: you’ve got to render the view that will be seen by each eye, and to reduce motion sickness you need to present at least 75 frames per second to the user—in console video games, 30 frames per second is considered passable.

It’s going to be a few years before mobile VR experiences can match the visual richness of the Infinity Blade series. EPIC GAMES

One prominent thesis among virtual reality’s proponents is that mobile solutions (i.e., a smartphone slotted into a headset) will be where VR goes mainstream. Mobile GPUs are improving rapidly, but improvements to visual quality aren’t straightforward. Competition continues to drive mobile screen resolutions higher, which removes visible pixels when strapped to one’s face in a headset, at the cost of graphics horsepower that could’ve been spent on pushing models, textures, and shaders—the factors typically used to determine graphical quality. While a game developer’s natural inclination may be to go after photorealistic graphics, in almost very circumstance it makes more sense to sacrifice detail for higher frame rates, which improves comfort throughout.

Thankfully, constraints can lead to creative solutions. As we’ve seen on previous generations of game consoles, there are plenty of techniques that can create beautiful visuals with limited resources, from cell shading to level-of-detail rendering.

The Legend of Zelda: Wind Waker‘s use of cell-shading techniques saved memory and made for a unique visual aesthetic. NINTENDO

It’s also probably a safe bet to assume that at least one major player in virtual reality headsets will introduce eye-tracking technology, which allows for simple input (wink to select, focus on a menu to open its options, etc.) as well as even more efficient rendering based on where a user is likely to look at any given time.

While resource constraints are certainly less of an issue on the gaming PCs that will power early consumer headsets, VR developers should still be aware of ways they can improve performance. Despite public enthusiasm, requiring a $600 graphics card just to render a scene properly will certainly hinder bringing high-end VR to a broader market.

Mobile VR also—for the time being, at least—lacks positional tracking, which uses a camera or sensor to detect a user’s location in space. (It’s what lets you lean forward in order to examine objects close-up, or look around corners.) That absence is an important limitation to consider when planning which platforms to address. If you develop a game for the Oculus Rift’s consumer headset and then decide to support mobile as well, the project must either diverge into two separate projects with shared assets or cut out positional tracking in order to support the lowest common denominator.

Pitfalls of the Easy Route

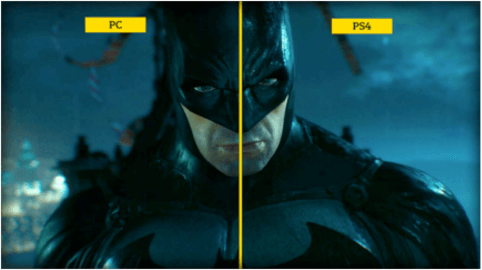

On the desktop and console side, porting traditional video games to the upcoming VR headsets seems like a cheap way to take advantage of early adopters hungry for real content. Publishers and developers should take heed, though: ports done by external teams tend to be poorly optimized, which in VR means users are going to quit because they are literally sickened by your product.

PC gamers (and VR early adopters) invest $1,000+ in their hardware. When publishers don’t make a commensurate investment in supporting the platform, it can feel like a massive slight. ROCKSTEADY/WARNER BROS. ENTERTAINMENT

Optimizing for VR means much more than getting frame rates to an acceptable threshold. Controls are also very important to re-consider. In first-person shooters on consoles and PC, player characters typically have a zero-degree turning radius—they turn on a dime as soon as you move the mouse or analog stick. In VR, a player’s perspective must be controlled by the actual movement of their body. And while a standard gamepad might be easier to develop for, people instinctually try to move their hands around in virtual experiences. It might take more effort, but users who get to interact with their environment using the upcoming motion controllers from Oculus and HTC will appreciate it.

There’s also the fundamental issue of expressing moment-to-moment narrative. Traditional first-person video games tend to tell their stories by cutting to cinematic clips or temporarily taking control over the player character’s perspective away from the player. In addition to the typically jarring transition this causes, it also breaks the illusion that the player is a person within the game scene.

Large and small players in the VR scene are aware of these hurdles; what isn’t clear is who will deal with them. Small indie teams, enthusiastic hobbyists, and CGI production houses are building the first wave of content for VR devices on the market, but they’re only tackling a subset of the challenges yet to be solved.

While a team of five developers working in their spare time might figure out how to draw someone’s attention to an important detail in a scene, there are some tasks that, for now, require significantly more resources to adequately address. Something as basic as communicating with in-game characters requires not only changing how we think of those interactions from how they’re done in video games today, but also a team of animators and voice actors and artists to make models that appear realistic (but not too realistic, or you risk falling into the Uncanny Valley).

The introduction of commercial headsets to the market is going to draw even more investment from major film and game studios to the platform over the next few years. As happened during film’s early transition from avant-garde creators to the studio system, innovation will occur continuously, from many sources and in many ways—until the creative process looks all but unrecognizable. We simply cannot guess at the future of VR based on what we have today.