Besides invisible messages, bigger and predictive emoji, full-screen effects, and movie/TV GIFs, Apple recently announced that stickers, too, are finally coming to its most popular app, iMessage. It’s no surprise that messaging is the company’s most popular app — if smartphones are like extensions of our fingers, then messaging is like touching people and things.

What is surprising — especially when compared to the more mature messaging ecosystem in Asia — is that many people still tend to treat stickers (i.e., the ability to easily incorporate pre-set images into texts) as just-for-fun frivolity, when they’re an important visual digital language fully capable of communicating a nuanced range of thoughts. For example, a single sticker could convey very different messages: “I’m so hungry I could collapse” or “I miss you” or “I’m sound asleep snoring”. Complex feelings, actions, punch lines, and memes are all possible with stickers.

They are an acceptable response to “end” a real-time back and forth conversation (great for punchlines). They are a low-risk way of saying hi and initiating a chat with an acquaintance. And they reduce the social friction of saying something emotional in text form; this is especially helpful in a culture that is known to be less outwardly expressive even to one’s own family members and friends (where it is far less awkward to send a virtual-fistbump sticker than it is to tell someone directly that they’re a wonderful friend).

And sometimes stickers can convey what words cannot! This form of visual communication has become so popular in Asia — especially in China’s WeChat and Japan’s LINE [Line] — that it is not uncommon to see a deep thread of multiple messages without a single word. They’re not just for those crazy young kids. More notably, stickers are commonly used in professional, not just personal, chats as well. Not so frivolous after all. In fact, stickers are so core to the success of Line, that its CEO actually credited them as the “turning point” for that app. He shared that it took Line Messenger almost four months to find its first two million users … but after stickers were launched, it took only two days to find the next million. The company now makes over $270M a year just from selling stickers.

So why have stickers taken off in these apps? How did they get started, how do they keep users engaged? Here are some elements in the success and spread of stickers as a visual communication medium.

Stickers as trading cards

In WeChat, stickers are like Pokémon trading cards: you collect them, you keep them, you share them when needed.

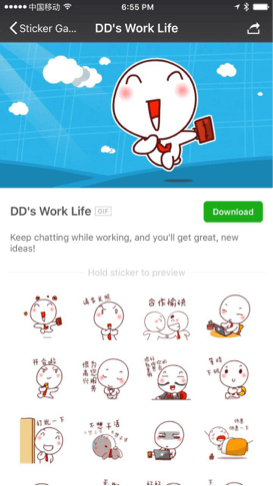

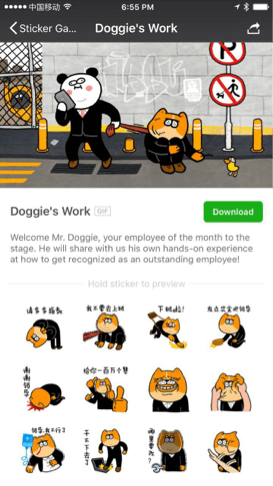

But this isn’t just about statically collecting and preserving a complete “set”, the way one might trade for and ultimately collect a set of Hall of Famer baseball cards. Stickers do exist in sets, as in the workplace sets launched by Tencent below to be used in office messaging conversations:

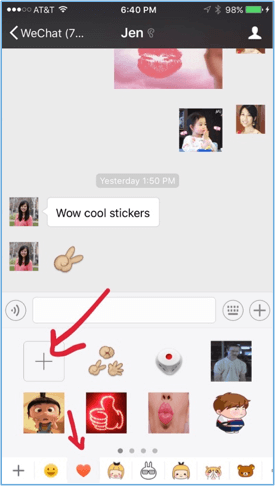

‘Wow cool stickers’

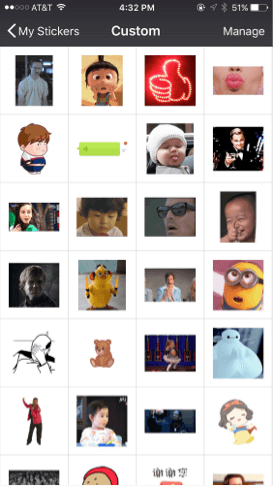

The “trading” element, however, is less about statically collecting and more about dynamically custom-curating one’s personal collection of stickers. These collections also signal one’s “sticker street cred” in Asian messaging apps — you can always tell a newbie or non-tech savvy user by their use of the stock stickers only.

So where then does the idea of trading come in? That element, I believe, has a lot to do with the way stickers were implemented at launch.

When WeChat first launched stickers, users had two ways of sourcing them: download approved sticker packs from the WeChat sticker gallery, or upload their own gifs and save them in a custom sticker folder. Unsurprisingly, most users did not go through the hassle of uploading their own stickers. But when just-enough users cumulatively did, WeChat soon had millions of crowdsourced, relevant gifs — already native for chat use given how they were created — circulating on the WeChat platform.

‘from the collection of Connie Chan’

What happened next is key: WeChat was careful not to make this a static upload/download activity from centralized sources — they injected a mechanic where if you received a custom sticker in a chat thread, you could easily save it to your own custom sticker folder, and wait for a great opportunity to use it (e.g., “trade it”) in another future conversation. Over time, collecting, having, and trading these stickers became a point of pride for savvy users, and saving and reusing them was natural.

The delight of collecting stickers becomes most apparent over holidays. In the early years of WeChat, when the winter holidays came around, users began sending each other custom animated gifs related to Christmas, New Year’s, or Chinese New Year. It’s the messaging-native equivalent of a free Christmas card. Soon, WeChat users would try to one-up each other — seeing who had the best sticker, the funniest sticker, the most beautiful sticker. It’s a mechanic that continually increases the use of stickers as a communication and signaling medium.

Stickers as marketplaces

The massive popularity of WeChat stickers and trading-card like behavior led WeChat to create a “sticker marketplace” for Chinese users in summer 2015. Line actually released a marketplace of its own earlier, in 2014 — the Line Creators Market, where designers worldwide could submit stickers to be sold on the app.

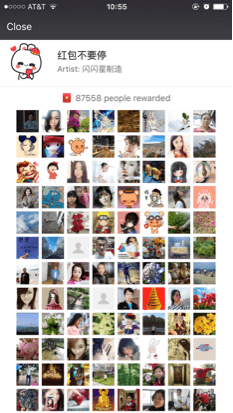

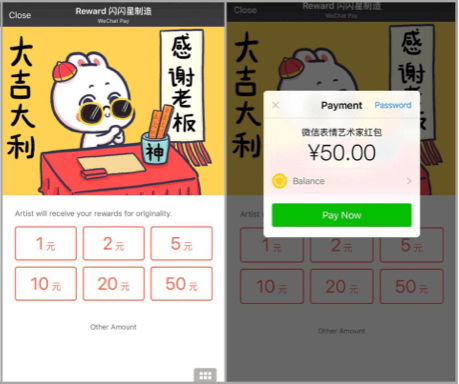

In WeChat, independent artists contribute their sticker creations and users can choose to reward these artists with cash donations, similar to “likes”, only with token amounts of money tied to them. While the dollar amount can be as small as $0.15, as with all things in China, the numbers add up given massive scale: This year, one artist received over $19K USD of donations for the Chinese New Year sticker set below:

Interestingly, instead of collecting a portion of the proceeds, WeChat allows artists to keep 100% of the proceeds. So what then does WeChat get out of it? More user engagement, and a high-quality variety of stickers that helps the platform go beyond just text and audio chat (and, frankly, their monetization model doesn’t center around stickers). For artists, the benefits are obvious: access and distribution, not to mention opportunities for iterative feedback from users.

Interestingly, instead of collecting a portion of the proceeds, WeChat allows artists to keep 100% of the proceeds. So what then does WeChat get out of it? More user engagement, and a high-quality variety of stickers that helps the platform go beyond just text and audio chat (and, frankly, their monetization model doesn’t center around stickers). For artists, the benefits are obvious: access and distribution, not to mention opportunities for iterative feedback from users.

This crowdsourced-curation marketplace model helps WeChat strike the balance of releasing their own “official stickers” while also allowing more expressive and fun messaging options for users. In the marketplace, users cast their votes for quality stickers with downloads. And as a platform, WeChat reviews new sticker submissions before they hit the marketplace. Algorithms are also in place that utilize usage data to promote the best stickers. Not only does this model open new revenue streams for quality content creators, it also helps discourage overuse of lower quality stickers (such as a 1MB+ huge animated gif or a highly inappropriate one), which could muddy the joy of discovery and ease of use.

Line, meanwhile, made stickers more central to its strategy, with over 390,000 creators from 156 countries submitting stickers for consideration in the first year of the marketplace alone. Responding to the high volume of submissions, Line soon after released Line Creators Management — a de facto digital talent-agency like service that helps sticker creators apply for trademarks, sign merchandising deals, and so on. This enables Line to take a portion of the sticker revenue but still ensure that their artists are incented to continue feeding the marketplace by helping them turn sticker creations into offline monetizable merchandise, such as stuffed animals or pencil cases. And that in turn creates an offline-to-online viral effect that reinforces the spread of the app through word-of-mouth through connection to the stickers in both digital and physical form.

Today, Line continues to introduce new types of stickers and new media sticker types, including audio stickers and soon pop-up stickers that will fill the entire chat screen. Imagine throwing a hammer to your friend to seemingly crack his or her entire phone screen (as you can already do with a sticker on Tencent’s other messaging service, QQ)!

Stickers as storytelling

Line stickers include not only crowdsourced content, but celebrity images/caricatures and other licensed IP. However, the stickers that have had the biggest engagement and impact on the app, are undoubtedly Line’s own character creations.

image: Line

Using stickers alone, Line launched an original cast of cartoon characters whose storylines and personalities are developed through subsequent sticker packs. Two of the most popular characters are a male bear named Brown and a female bunny named Cony. These characters became so popular, that they now have their own TV show, books, merchandise lines, and even third-party product endorsements: You can find their faces on cellphone cases, notebooks, pens, figurines, cupcake toppings, billboards for chewing gum, and more.

This phenomenon is not unlike the Sanrio Hello Kitty and friends phenomenon, with its popular characters and storytelling through merchandising alone. Only this phenomenon has been developed by and within a messaging app (vs. led by toy manufacturers). WeChat, too, is now taking a page out of the Line playbook and turning its most popular sticker pack into a limited edition McDonald’s toy in China. (It already had a popular sticker-character on its platform that was also a physical toy, as described here).

With fresh, distinct, and relatable stickers, Line clearly struck an emotional nerve that resonated and continues to resonates with users. So how did they do it? The key was thinking of stickers not just as object but medium, and character development is a key part of that.

Being headquartered in Japan, home of anime, may have given Line a home court advantage here. In any case, the company understood that the best stickers go beyond phrases (“I’m hungry”) to depicting full moments of reaction, as stills/ GIFs from a movie do. The best stickers therefore capture or exaggerate the feelings of the sender — after all, only then could stickers completely replace text.

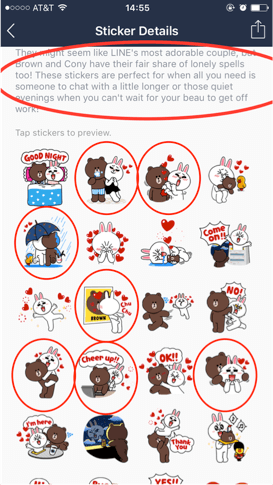

This mindset makes a huge difference in how the stickers are designed — they’re less predictable, more multifaceted expressions yet are still grounded in everyday, user-relevant actions. Watch this short animation clip of Line’s Brown and Cony characters going on a date; then look closely at the sticker pack below it that was released based on stills from the cartoon.

The point is not that the cartoon drives the sticker adoption (it doesn’t) — but rather that this mindset of stickers-as-storytelling drives the very designs of the stickers. By showing the characters in a relatable scene, or engaged in an everyday act, stickers provide more variables to help the receiver decipher the true intent of the sender. These “storytelling” types of stickers therefore embed entire moments, not isolated facial expressions or singular emotions like emoji, in a single image — making them more of a complete, even self-contained communication medium.

The point is not that the cartoon drives the sticker adoption (it doesn’t) — but rather that this mindset of stickers-as-storytelling drives the very designs of the stickers. By showing the characters in a relatable scene, or engaged in an everyday act, stickers provide more variables to help the receiver decipher the true intent of the sender. These “storytelling” types of stickers therefore embed entire moments, not isolated facial expressions or singular emotions like emoji, in a single image — making them more of a complete, even self-contained communication medium.

Monetizing stickers

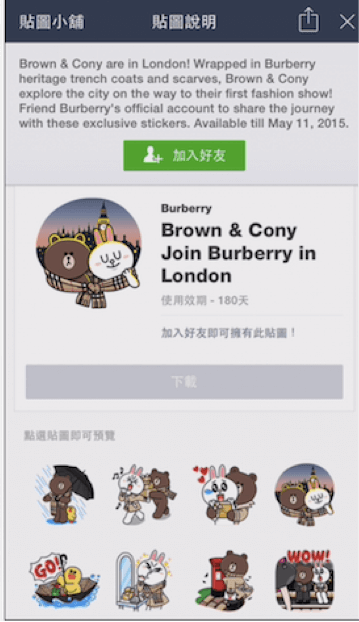

Of all the messaging apps out there, Line Messenger is the leader in monetizing stickers. One way they do this is through the character stories above, but with brands. For example, Burberry built Brown and Cony into a brand story/ advertising campaign around the characters’ adventures in London. The video features Anna Wintour, Cara Delevingne, Christopher Bailey, and Mario Testino, but the stickers based on this campaign focus primarily on Brown and Cony’s love for Burberry and London (at left).

Of all the messaging apps out there, Line Messenger is the leader in monetizing stickers. One way they do this is through the character stories above, but with brands. For example, Burberry built Brown and Cony into a brand story/ advertising campaign around the characters’ adventures in London. The video features Anna Wintour, Cara Delevingne, Christopher Bailey, and Mario Testino, but the stickers based on this campaign focus primarily on Brown and Cony’s love for Burberry and London (at left).

What fan of Burberry and/or Brown and Cony wouldn’t want to include these stickers in their custom set? If fashion brands are signaling, then stickers coupled with fashion is a 10x version of that!

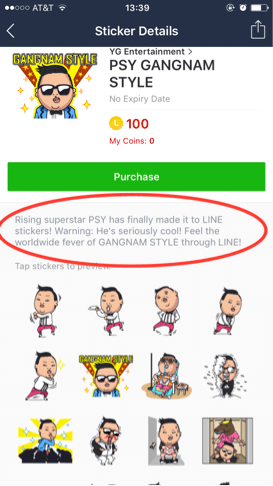

Besides lovable bears and bunnies and signature plaid, real-life celebrities make frequent appearances in the Line sticker store, too. They (and Line) earn money by taking a cut of sticker revenue. For instance, South Korean pop stars coming out of the very audiovisual “k-pop” genre have run sticker promotions where all users who purchase a special edition sticker pack get to listen to a newly released song. Most paid sticker packs cost around $1.99 USD, and because people pay, Line can then use stickers as financial carrots to entice even more influencers to join and participate in its platform, creating a network effect flywheel of sorts.

Besides lovable bears and bunnies and signature plaid, real-life celebrities make frequent appearances in the Line sticker store, too. They (and Line) earn money by taking a cut of sticker revenue. For instance, South Korean pop stars coming out of the very audiovisual “k-pop” genre have run sticker promotions where all users who purchase a special edition sticker pack get to listen to a newly released song. Most paid sticker packs cost around $1.99 USD, and because people pay, Line can then use stickers as financial carrots to entice even more influencers to join and participate in its platform, creating a network effect flywheel of sorts.

The celebrity appeal is not only confined to Asian pop-stars and brands popular in Asia however; Western brands and celebrities that have already built followings on Line include other fashion brands like Dior, beauty and CPG brands like Clinique and Coca Cola, shows like Family Guy, and musical bands and artists such as Linkin Park, Paul McCartney, and Taylor Swift.

photo: Jon Russell / Flickr

Finally, Line monetizes stickers through thorough online-to-offline merchandising beyond Brown and Cony; the company also decided to open an offline holiday pop-up shop in Times Square, NYC.

These Line pop-up shops are wildly popular and have been launched in several countries around the world.

Given this offline phenomenon, it’s not that far-fetched to imagine that the next Mickey Mouse — and perhaps even the next Disneyworld built around a family of characters — will come from a sticker set.

On selfies as stickers

Stickers are a communication medium, and for that matter, so are selfies. But I’d even argue that selfies are a form of stickers (which partly helps explain the success of apps like Snapchat). How? When you add all the layers of animations and other elements to selfies — filters, fun borders, gimmicky hats, glasses, puppy ears, and more — the end products are not just selfies, but stickers.

There are two kinds of stickers — stickers where the entire image is computer generated, and stickers where animated graphics are used to decorate a digital photo (this is not unlike the distinction between VR and AR, where the former is immersive and entirely computer created and the latter is a layer on top of reality).

This second kind of sticker, which Snapchat selfie lenses embody, was first invented and popularized in Asia through the “Purikura” sticker booth phenomenon started in Japan in 1995 (two decades before the first Snapchat selfie lens). In these photo booths, people would take photos of themselves and then race outside the photo booth, where they have several minutes to decorate their photos with as many digital flowers, letters, borders, glasses, text bubbles as they’d like. These booths were even smart enough to change the shape of your eyes or alter the hues of your skin tone if you wanted to. These booths are still popular today across East Asia.

And now, that phenomenon is spreading digitally through stickers and selfies-as-stickers in messaging apps. The beauty of selfies as stickers is that the emotional connection people have with their own likeness is a given — from before even the time of Narcissus — and that’s why acquisitions like Bitmoji matter beyond the obvious, surface use case. While bitmoji are not stickers (or selfies) per se, they blend the selfie with the storytelling and sharing element of stickers. Where another user probably wouldn’t share your selfie, they are more likely to post and share your selfie-as-sticker, or respond in kind — a phenomenon that more easily spreads virally in group chats, such as with families on WhatsApp or in other groups on messaging apps.

* * *

Sending a sticker of Brown giving Cony a hug from behind conveys a thank you or comforting positive feeling… or it carries a sense of flirting and romantic closeness. It could also just be a simple thank you message. The ability for the sender to hide behind the ambiguity is precisely why the sticker in this instance is more effective than words or even emoji. The sticker allows for implicit messages to enter our otherwise explicit conversations in a natural way, making the use of messaging apps not just fun but even more sticky (no pun intended!) for users.

With over 4.2B messages sent, 16.2B messages received, and over 389M stickers sent on Line’s platform per day, roughly 1 in 11 messages currently contain a sticker. More notably, many of those stickers are sent as a standalone message. Furthermore, usage isn’t limited to young teenagers, but has permeated the entire Line user base, delighting young and old alike.

Stickers aren’t just frivolous little punctuation marks to be inserted in text messages. They can be replacements for entire sentences, and help create a new medium for communicating and storytelling.

Editor: Sonal Chokshi @smc90