China has been in the headlines lately for the ongoing acceleration of its capital outflows and concerns over the reliability of its reported economic data. As various businesses and investors hastily adjust their forecasts and expectations, to me, this period of uncertainty represents an opportunity for U.S. companies: To take the time to learn, reflect, and consider what their China strategy should be. (I share specific strategies for how to approach a China strategy in part two of this post.)

But first, doing business with — or in — China requires understanding nuances that go beyond the stats and typical headlines. Until now, most entrepreneurs and commenters have been so focused on the obvious market size opportunity that they often forget the less obvious reason to study China: That there is much to learn from, not just about, Chinese companies. This includes everything from redefining how we think of innovation and how internet companies can monetize beyond advertising revenue to lessons on how startups can scale in a hyper-urban environment.

Frankly, while China is behind the U.S. in areas like enterprise SaaS, augmented reality, VR, and healthcare, it can provide a glimpse of the future in other areas, such as mobile payments; transportation; O2O or “online to offline” commerce (coined by my a16z partner Alex Rampell and popular in China); ecommerce and travel.

Ultimately, however, learning from China involves rethinking our mindsets around it … beginning with how to be open to learning from China in the first place, to preparing for future competition from there as Chinese companies aim to realize their global ambitions.

Mindset #1: Rethinking the definition of “innovation”

A long-held and common belief about Chinese, Indian, African, and other non-Western internet companies is that they are just copycats of U.S. counterparts. Even the language we (and sometimes they, too) use propagates this misconception: e.g., Alibaba as the “eBay of China”; Flipkart as the “Amazon of India”; the “Groupon of Iran”, and so on.

Derivatively calling a company the “X brand (we’re familiar with) of Y country” tricks us into thinking that those companies are just clones of the original U.S. company. Yet the reality is there’s a ton of grit and creative thinking that led the entrepreneurs behind Alibaba and others to build their companies the way they did. Furthermore, examples of international companies leading — not just following — U.S. innovation now abound, from messaging app WeChat to drone manufacturer DJI in China alone.

There are also a number of enabling conditions that make Chinese companies do things in a way that U.S. companies aren’t forced to. For example, the speed at which things move in China is unprecedented, and the sheer number of people makes it an eat-or-be-eaten environment that urges forward momentum in all things and at any cost. Chinese companies are therefore used to lightning-fast execution, shorter product cycles, and letting a thousand experiments bloom (even if 999 of them fail and have to be ripped out!). I believe that U.S. companies should closely watch all these Chinese experiments play out — not just to inspire their own experiments, but as proxies to focus their own efforts directionally.

Now, some may argue that many of these innovations are really just “incremental” (as compared to 10x magnitude leaps or moonshots). But when compounded, seemingly incremental improvements can lead to bigger things in their own right. Especially when combined with a mobile-first ecosystem.

Take the example of Chinese online travel provider C-trip, which not only offers flight and hotel bookings but insurance and visas as well. Because over 70% of its online transactions are mobile, the company thinks deeply about the needs of mobile travelers. So in 2015, C-trip launched a “virtual tour manager” program, where it creates WeChat messaging groups for individual travelers heading to the same city around the same time. Each of these groups are administered by a human tour guide who helps book restaurants, looks up traffic patterns on travel routes, and sends alerts in case of emergencies (about earthquakes, attacks, etc.) — all in Mandarin Chinese.

This service is now live for over 100 countries. It’s an example of a Chinese tech company stretching its creativity to meet unarticulated user needs. But what if this small customer service innovation led to an entirely new kind of communication model, one that facilitates communication among complete strangers? And on a far more intimate platform — something normally reserved for friends, families, and close-ties groups — than on the likes of Sina Weibo or Twitter? If so, the resulting changes in social behaviors could be profound.

Another example of a seemingly incremental innovation that could have significant consequences comes from Didi, China’s leading ride-hailing service. The company, which provided 1.4 billion rides in 2015, installed touchscreen booths — really, gigantic tablets mounted on displays — all around Shanghai so that people (especially the elderly) could still hail a Didi car without having a smartphone.

It’s a convenient but relatively minor service. Yet if this kind of thing spread, it could reshape the way entire cities look, as public surfaces everywhere become the “shared phone screen” (i.e., instead of something held as a central command center only in an individual’s hands).

Beyond such product inspiration, there are incremental business model (not just tech) experiments that can change century-old practices — like reading and storytelling — in potentially far-reaching ways. Consider China’s largest online/ebook publishing company, Yuewen Group, which has over three million digital books in its catalogue. More notable than the scale here however is how the company monetizes: Chinese readers can pay per every 1000 words (sort of like by chapter), and have been able to do so for more than half a decade.

Not only does this micro-transaction model encourage more readers to sample more e-books while providing instant revenue to writers (who can begin selling a book right after the first chapter is completed), the collected data can help TV producers make series-optioning decisions at a more granular level. But the unintended consequence of all this is that authors with extremely popular books never want the story to end, changing the narrative significantly. Over time, it could even change the act of storytelling altogether; it’s not unlike what’s already happening in the U.S. with shows like Game of Thrones or with binge watching/streaming leading to an entirely new genre of entertainment.

More broadly speaking, Yuewen is also an example of how Chinese and Western users monetize differently across multiple tech categories. For instance, less than 20% of Tencent’s (the creator of WeChat) revenues come from advertising compared to over 95% for Facebook’s revenue. In fact, most large consumer mobile companies in China (and elsewhere around the world) do not rely on advertising as their primary source of revenue; they focus on transactions instead. Chinese internet companies have therefore experimented with numerous non-advertising business models including in-app or in-game fees, other microtransaction models, free-to-play, and more. For a U.S. company that was previously monetizing only via ads, studying its Chinese counterpart could reveal alternative ways of generating revenue so it’s less dependent on advertising as many U.S. internet companies are.

Mindset #2 Rethinking scale, and scaling

Despite conflicting views on the actual growth rate of the Chinese economy, no one would question the growth rate of China’s population! When we read headlines about tech companies in China, the true scale of the reported user stats often get lost in translation. Part of this is because most people — journalists and readers alike — have simply not been exposed to such population density. And as with other classic estimation experiments, people are just really bad at imagining (let alone visualizing) the true magnitude of things they haven’t experienced personally.

To put it bluntly, a company that has reached 1 million registered users in China hasn’t really “cracked” China; for instance, if Tencent had a product with just five million monthly active users in China, it might consider shutting the app down! Now, to be fair, reaching a million users is an achievement to be celebrated. And even relatively smaller numbers compared to the actual size of the Chinese market can yield huge business gains. But it’s important to keep the numbers in perspective…

China has a lot of people. Shanghai and Beijing alone have 20 million residents, each. Compare this to New York City’s population (8.4 million), Los Angeles’ (3.9 million), and San Francisco’s (less than 1 million). And while some ghost towns exist do in China, there are still 1.3 billion people in China; if you took China’s total population and subtracted out the entire population of the United States, you would still have a billion people left.

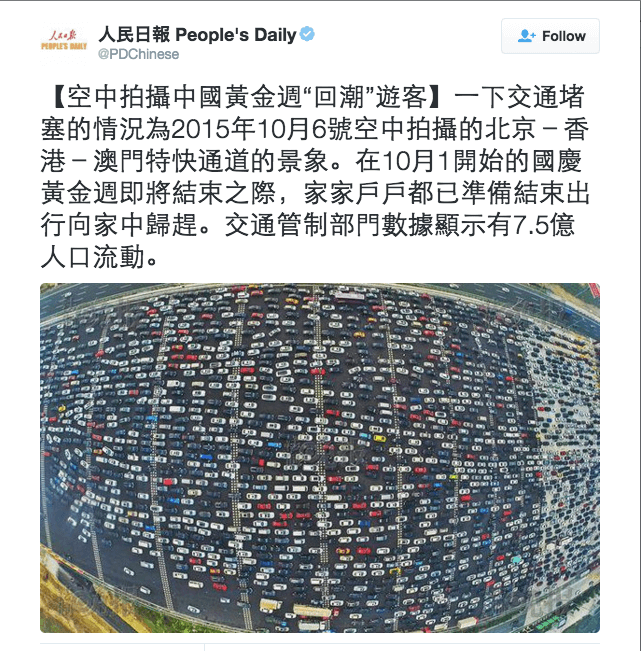

a 50-lane traffic jam in Beijing

Now tack on the news that China is committed to moving 100 million Chinese people from rural farming regions into more urban regions in the next five years. Beijing, Shanghai, and other major cities in China continue to face hyper-urbanization issues that will force them to go where no other modern city has gone before. Already, China’s biggest cities are overflowing to such a point that license plates are distributed via a lottery system to control the number of cars on the road. This has been the case in Beijing since 2011, and in Shanghai since 2013.

[Also check out these photos by Reuters’ Carlos Barria for before and after shots of Shanghai’s growth.]

Meanwhile, in mobile, China Mobile apparently has (as of the end of last year) nearly as many 4G mobile subscribers as the entire U.S. population. Not to mention nearly three times as many total customers as there are people in the U.S.

China is thus an ideal place for startups to find all sorts of insights on user behaviors at scale, whether one believes in the concepts of “blitzscaling” or not. Watching Chinese experiments play out also helps indicate what new problems (and solutions) will arise in urban centers around the world — especially on the transportation, logistics, and infrastructure front — as they, too, become more densely populated.

If being first to scale is indeed more important than being first to market, what better place to study scaling strategies than in China, a country with a population of 1.3 billion people?

Mindset #3 Rethinking the nature of competition

Last year, investors both in and out of China deployed $37 billion into Chinese startups (more than double 2014 and more than 8x of 2013). We can debate the record speed of new businesses being created, observe the problem of overfunding at the seed stage (and subsequent difficulty of meeting milestones later), or question private valuations of specific companies. But one thing is undisputable: Many startups in China are getting funded in some form or another.

Why does this matter? Simply put, if a startup is an experiment in a new way of doing things, then that means many experiments in China are happening overall. While it’s true that more global funding went into U.S. startups in 2015, the U.S. and Chinese startup ecosystems are different. Both ecosystems may have a winner-take-all dynamic, but that dynamic is far more intense in China. This results in far more trial-and-error — as well as rapid product cycles — as companies attempt to win market share from each other, quickly. Such rapid experimentation in turn leads to much faster change, willingness to accept and allow faster company deaths, and faster potential breakaway hits.

When you take this environment of experimentation, supported by so much funding, and combine it with a “Chinese” work ethic and talent base, it results in a “multiplier” effect of sorts. To break the components of that effect down further:

War games mindset. Company executives in China are trained, at the outset, to think in terms of war analogies, with the ultimate goal of outlasting the competition. This mindset leads to a sort of Hunger Games-like paranoia where “only the paranoid survive” (to borrow Andy Grove’s phrase), which in turn drives continual improvement, results in more experiments as described above, and gives Chinese companies more optionality than Western companies. Finally, since entrepreneurs are always under direct attack from competitors, they are groomed to fight defensively and offensively. Even PR is used as a weapon: For instance, funding announcements are made (and sometimes inflated) to discourage investors from backing competitors.

Work ethic. The average number of hours worked in China per worker in 2015 was 2,432 hours and 1,767 in the U.S. (Germany, meanwhile, comes in at 1,372 and France at 1,495). On average, the Chinese worker is likely working more than the U.S. worker; note however that this data includes factory workers and does not measure efficiency of work. Regardless, labor is obviously cheap in China. Furthermore, a standard workday in China is 9AM to 9PM, and a standard work-week is 6 days long, from Monday through Saturday. This schedule is not just for a special event or right before a product launch; it’s the norm in China. In the same way that people hypothesize that Europe is lagging behind the U.S. due to a different work ethic (among other policy reasons), the same could one day be argued of China and the United States.

Talent landscape. The talent landscape in China for engineers has changed so drastically in the last few years that some Chinese companies are actually coming to Silicon Valley to hire big data engineers because they are “cheaper” here. While so far limited to the big data space, this is a huge inversion of the traditional outsourcing model! Meanwhile, many Chinese tech companies appear bloated compared to their U.S. counterparts because they have many more employees including engineers. This is because companies in China can’t afford to wait to hire that elusive 10x engineer. Instead of risking falling behind, they’ll just hire the 10 engineers they can hire today (even if less skilled) to get the job done faster. This mentality applies to international expansion as well.

It’s a mistake to think this phenomenon is all about quality of talent: It’s really about the pace of competition. That’s the salient point here.

So why does any of this matter to anyone outside China? Because not only are a ton of companies — and experiments — in China getting funded, they’re run in an intense environment. The result of this intense Darwinian struggle for survival is that the species that survives is very fit. Those surviving companies will become formidable global players, which is why I think it’s worth learning from — and possibly partnering with — them now. Eventually, as Chinese companies enter the global arena, all U.S. startups will need to compete in such an intense environment or learn to stay ahead in other ways regardless of whether or not they enter China.

Mindset #4: Rethinking what “local” advantage means

When eBay entered China, Alibaba founder and chairman Jack Ma described it as “a shark in the ocean”. He said, “I am a crocodile in the Yangtze River. If we fight in the ocean, we lose, but if we fight in the river, we win.”

What Ma meant was that he understood the smaller Chinese merchants and consumers far better than eBay did; this included everything from where to find them to how to keep them engaged. Ma’s local competitor to eBay, Taobao, used TV ads and door-to-door sales reps instead of internet-based advertising. It made listings more customer- vs. product-centric. It optimized its marketplace model for Chinese notions of trust.

Unfortunately, when many entrepreneurs discuss “local” understanding or localization of their offerings, they tend to focus on things like the color palette, logo, design layout, language, even etiquette. All of which matters, but ignores fundamental insights about customers that take form in many other specific yet subtle ways.

For example: Chinese consumers really, really, really love deals and discounts. Even if a particular U.S. startup doesn’t offer discounts for its product, it should consider doing so in China (though obviously not at the expense of its unit economics!) — especially around the holidays. Similarly, even if it feels cheesy or passé to a U.S. audience, companies doing business in China should recognize how effective celebrity endorsements and physical billboard or elevator poster advertising are. And so on.

Another example of local advantage — but at a global scale — plays out in emerging economies. U.S. companies are more adept than Chinese ones at designing high-tech products for a demographic that closely resembles Western Europe. But Chinese companies can more quickly gain market share in emerging economies (like those in Africa, Eastern Europe, and Southeast Asia) since they are already experts in serving a user base that is mobile-first and Android-centric; limited in bandwidth or power; highly engaged and motivated by entertainment apps; hyper-urbanized; young in internet use; and so on.

In short, there will likely be not one but two stables of “unicorns”: one in the Western world, and one stabled in China and developing regions. Because even if many of these developing regions have far more in common ideologically with the U.S. than with China, Chinese companies could still win in those markets for the reasons I just outlined.

This suggests a paradox: U.S. companies’ greatest competition isn’t their local competitor but their counterpart abroad, wherever they are — the international #1, not just the local #2. And sometimes the competition isn’t obvious but lying latent in wait. An example of this is Cheetah Mobile, the creator of CM Security, Clean Master, Battery Doctor, and other smartphone apps. Across its suite of utility apps, Cheetah reportedly has 567 million MAUs — 74% of which are not in China. Cheetah took its product (which was already refined and robust from Chinese users heavily pounding away at it), localized it for the rest of the world with very little extra work, and quickly grabbed global market share. In fact, 4 of the top 5 free apps in the U.S. Google Play store tools category are apps that originated in China. This isn’t just happening in the “invisible” tools category; right now, 3 of the top 10 free apps in the photography category on the U.S. Google Play store are also made in China.

* * *

Many of the examples I share are anecdotal, because I’m arguing for two kinds of learning from China: passively watching (as described in the first two mindsets above), and/or actively learning to prepare for the competition (as described in the last two mindsets).

Whatever else one thinks of China, we need to accept that:

- Chinese companies are truly innovating, not just copying — if not in tech, then certainly in product, path to market, or monetization;

- Chinese companies are hyperscaling more intensely than U.S. counterparts because the TAM is much larger;

- Lots of Chinese companies are getting funded and competing in a super intense way (through a combination of long hours and “we’re at war” mentality) — so winners will emerge very strong; and

- Chinese companies can serve as both a source of inspiration in the short term and as a formidable source of competition in the future (and part of the art of partnering with them is realizing this; more on that later).

The government, of course, plays a role here for better or worse. For example, it is mandating that companies expand globally. Starting this year, the government will also create incentives for high-tech investors to take even larger risks on startups, which changes the risk:reward ratio. Either way, the outcomes don’t change much for us. It just means more global ambitions and experiments keep getting funded. (And even if they don’t survive to the next stage, those learnings will cycle through the Chinese startup ecosystem in some form, manifesting themselves in later companies as is the case in startup ecosystems all over the world.)

Now, none of this is intended to alarm or make us double up our workloads. There are unique attributes of Silicon Valley that enable it to continually innovate that other parts of the world haven’t really been able to replicate. This is simply a call for U.S. companies to critically evaluate how they match up against their competitors in China, to take that competition more seriously than ever, and really learn from them.

When considering their true competition, most U.S. companies intuitively list their domestic and local counterparts only. But does it only matter that one is faster than the second or third athlete in the race — or does it matter more that they know where the finish line is? In that sense, why should the #1 company in the U.S. only watch players #2 and #3 in their home market when it can also study (and possibly even partner with) its #1 counterpart in China or elsewhere? To me, “competition” isn’t just about who is taking market share away from you in that moment or place; it’s about who can help inspire your roadmap, who can really help drive you forward. That’s what innovation is after all: It’s about finding a better way of doing things.

This article first appeared in Forbes.