Credit cards and payment cards are arguably the most valuable network in the world, with at least $1 trillion of publicly traded market cap. On September 18, 1958—61 years ago today—it all began in the little town of Fresno, California.

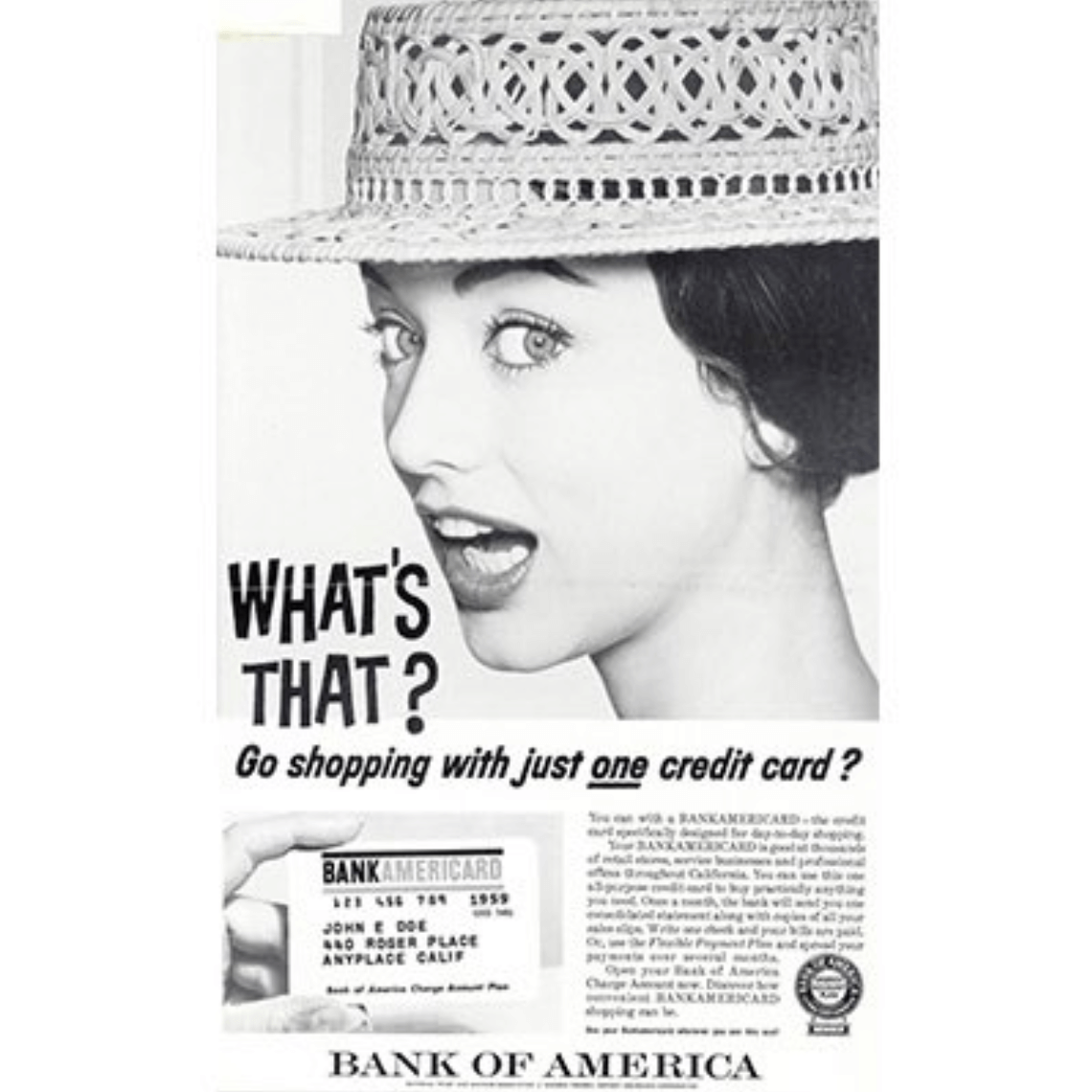

At the time, there were “charge cards,” like Diner’s Club, but there was no “credit” being extended. For consumers, lines of credit were either specific to a merchant (like Sears), or a burdensome process. If you wanted to get a loan, you had to go to the bank in person.

Back then, Bank of America was still a California-only operation. Fresno’s population was about 250,000 people and 45 percent of all Fresno families were Bank of America customers. The concept for the credit card emerged out of the bank’s corporate think tank, called the “Customer Services Research Department,” run by a 41-year-old named Joe Williams. Williams thought a multi-merchant credit card could provide two benefits: convenience (don’t carry cash!) and lending (don’t apply for more and more loans, let your whole balance “revolve” if you want).

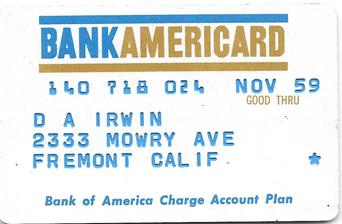

On September 18, the bank mailed 60,000 Fresno residents a BankAmericard. There was no application process. The card simply arrived in the mailbox, ready to use. Credit card fees for merchants were set at 6 percent and consumers received between $300 and $500 in instant credit. There was a certain brilliance behind the 60,000-person drop: On day 1, cardholders simply existed. This permitted Bank of America to sign up all merchants who didn’t already have proprietary credit card programs. BofA focused on fast-moving, small merchants like Florsheim Shoes, not giants like Sears. More than 300 Fresno merchants signed up.

Within three months, Bank of America had expanded its customer base to Modesto in the north and Bakersfield to the south. Within a year, it added San Francisco, Sacramento, and Los Angeles. Thirteen months after the initial Fresno drop, the bank had issued 2 million cards and onboarded 20,000 merchants.

Joe Williams, the card’s original mastermind, had assumed that collections would be a breeze, late payments would never cross 4 percent, and existing bank credit systems would work. Instead, his optimistic projections did not hold. Simply giving people credit cards created far more bad debt than Bank of America had ever seen (on a customer % basis). Delinquencies were over 20 percent. Merchants hated paying 6 percent fees. Criminals quickly figured out how to replicate the cards, and fraud grew out of control. Less than two years after the Fresno drop, Williams quit. The credit card almost died then and there.

But against all odds, Bank of America persevered with the BankAmericard. Within a few years, BankAmericard turned a profit. Eventually, BankAmericard became a non-profit consortium called Visa, uniting many banks with competing credit cards. Another consortium called MasterCharge (later MasterCard) did the same with a different set of banks. The credit card grew like a rocketship, transforming how people pay and borrow. The rest is history.

Read Joe Nocera’s Piece of the Action for more.