This was originally posted on the a16z Growth Newsletter on Substack. To receive analysis like this in your inbox early—plus additional media recommendations and insights from the Growth team—be sure to subscribe.

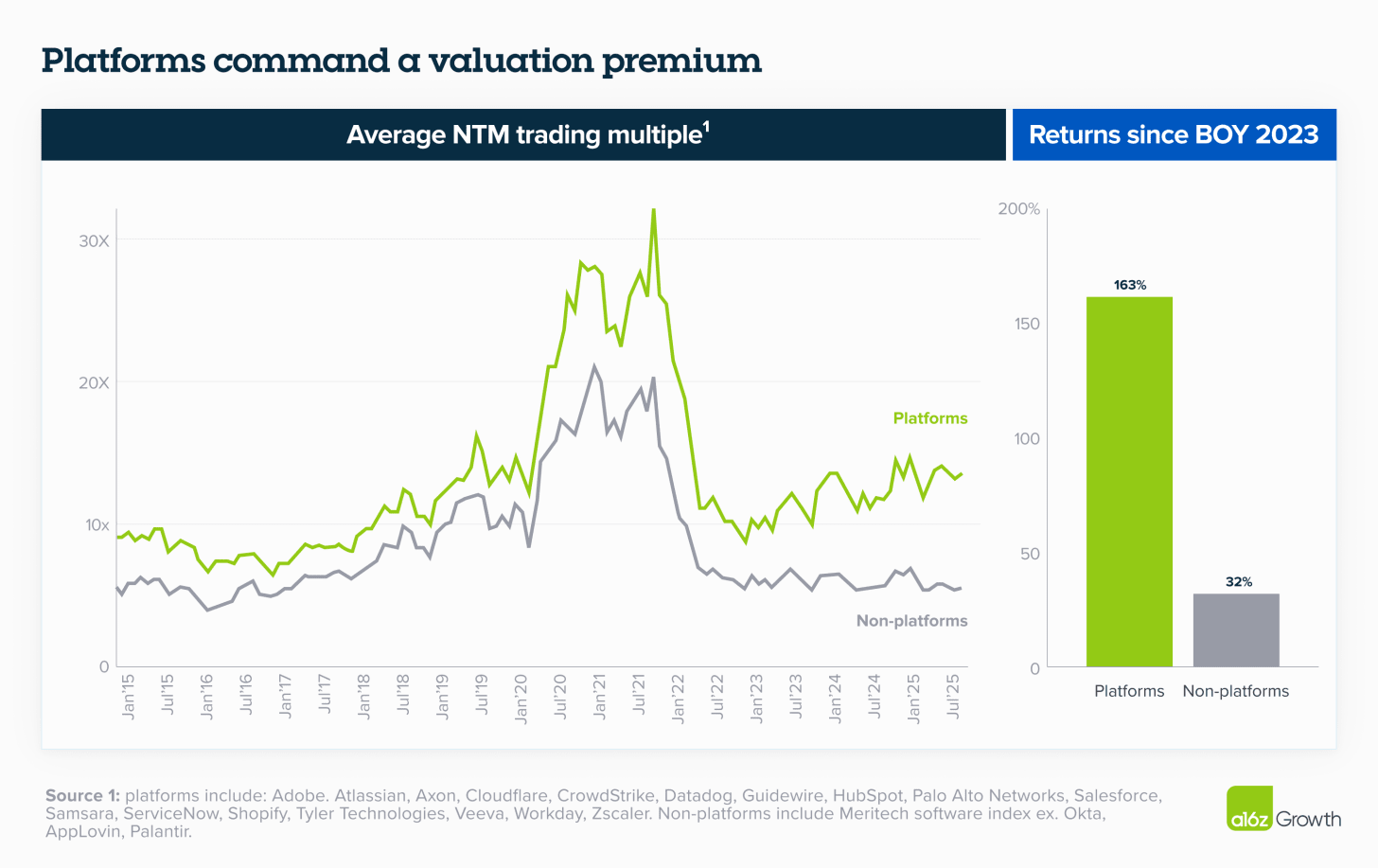

Plenty of people talk about building platform companies, and for good reason. Platform businesses can trade at hefty premiums and are responsible for the lion’s share of software market cap appreciation over the last five years.

But we can all agree that the word “platform” has become one of the most over-used terms in enterprise software. Of course, it’s tempting for companies to talk about their platform opportunity, regardless of what the product does or how it’s built. And great product people will say that the defining feature of a platform is that it’s extensible—meaning that their users can write their own code natively within their product. But from an investor’s perspective, they’re missing another piece of the puzzle.

A true enterprise platform is a market-leading company with a single suite of products that gets stronger as it accumulates new data and ships new products. Every module sold, every workflow instrumented, and every integration built feeds back into deeper customer insights and stickier relationships. That strong customer relationship earns the company the right to expand their wallet share and cross-sell their other products. These are the companies that have customers saying: “my shopping list this year is Company X’s roadmap.”

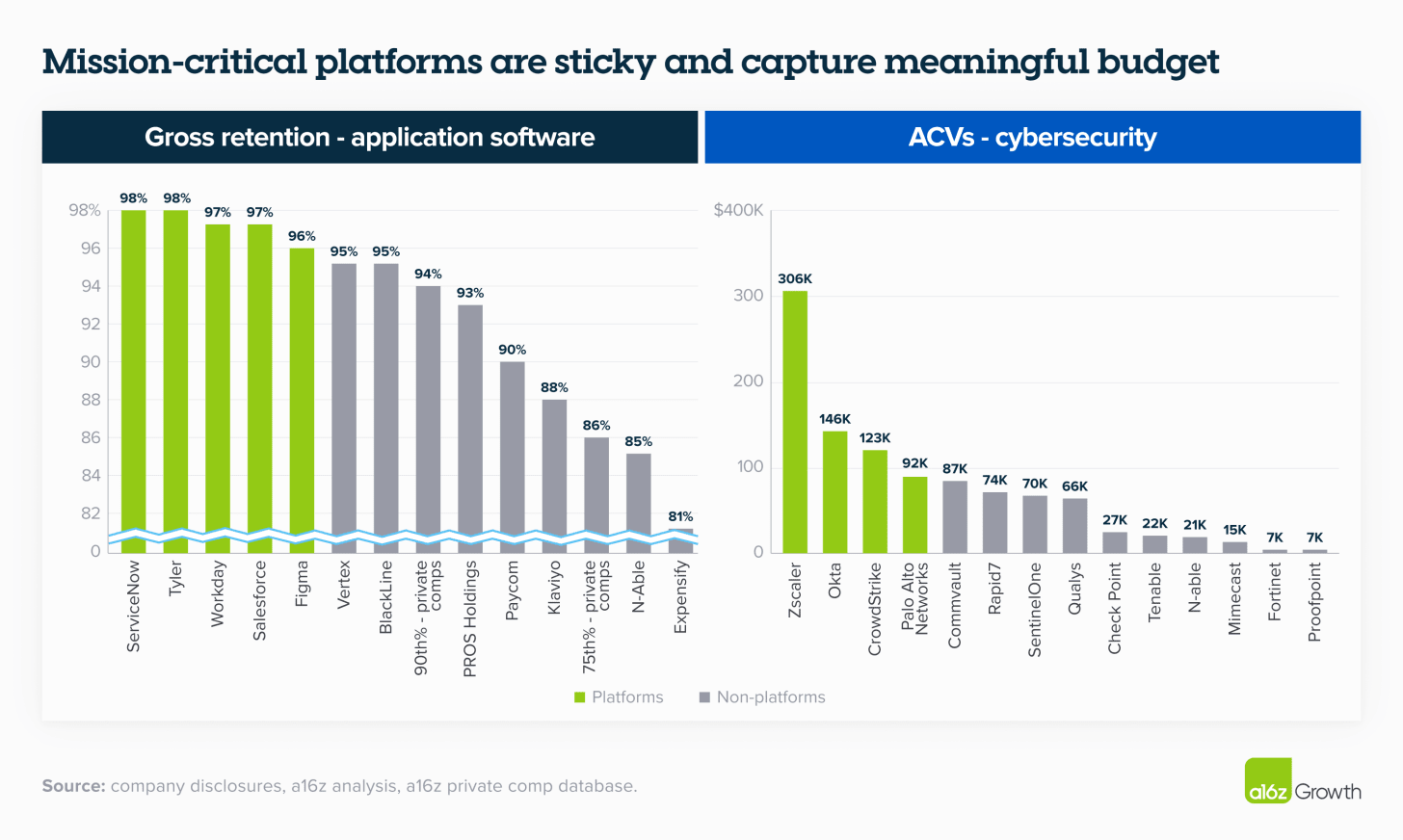

We’re fortunate to have seen many true enterprise platforms grow through the private and public markets since we started the Growth fund in 2019. While each platform looks a little bit different, we’ve found that platform companies at steady state tend to converge on the following key characteristics:

- Mission critical to customers, resulting in meaningful allocation of customer budget and strong gross dollar retention

- Market leadership in core market, as evidenced by high relative market share, pricing power, and sales efficiency

- Increasing returns to scale, fueled by network effects within the customer base and multi-module adoption

- Expanding TAM, driven by product expansion and distribution advantages

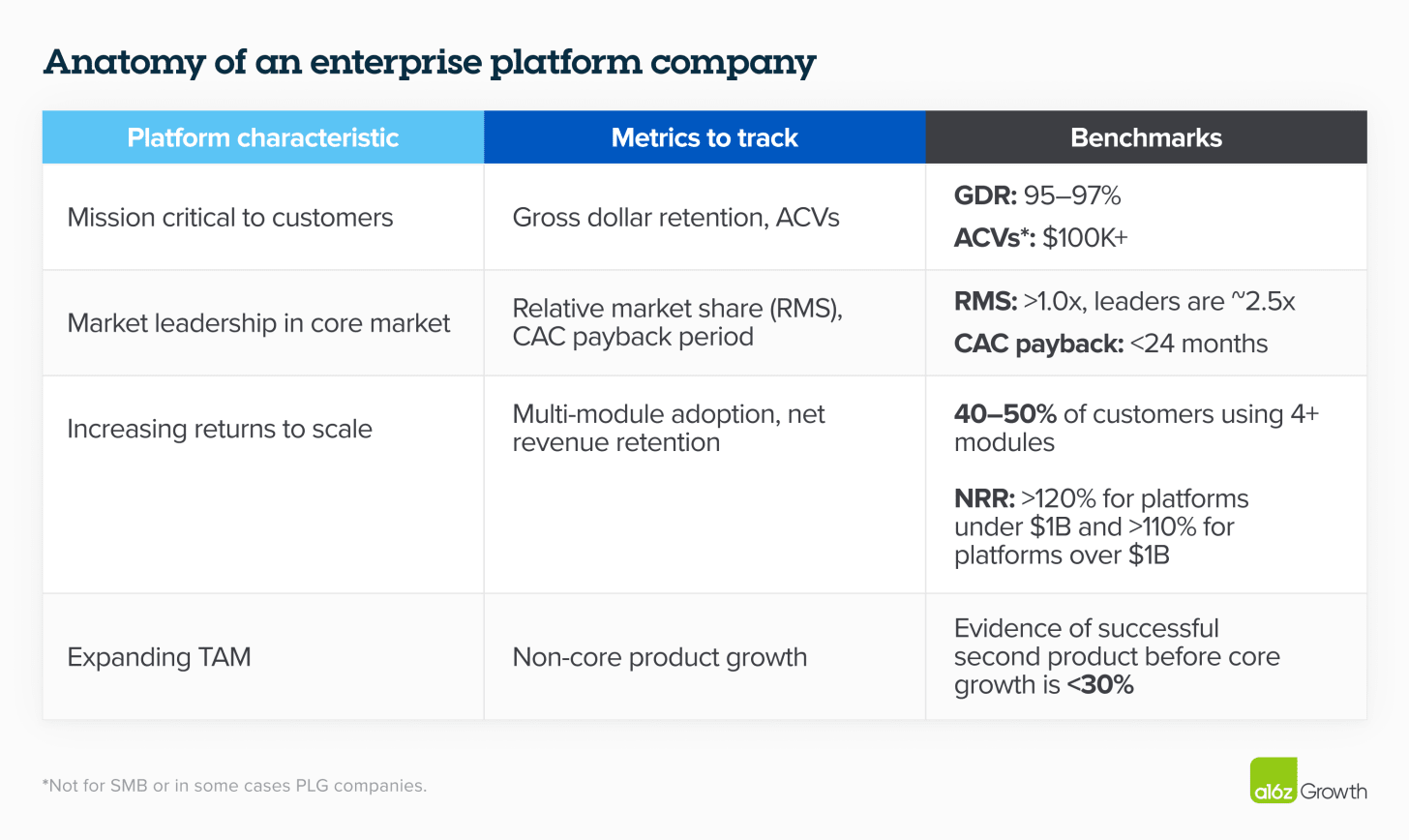

Mission critical to customers

Platform companies solve mission-critical problems for their customers, which drives deep, long-term partnerships and meaningful budget allocation. When customers devote significant time and money to integrating your solution into their core workflows, they’re signaling commitment that goes far beyond a simple software purchase. You become integral to your customer’s success.

Platforms need markets with sufficient size and budget to unlock their compounding advantages, so they typically target critical functions across horizontal markets (e.g., sales, HR, cybersecurity) or aim to capture a significant wallet share within large vertical software stacks (e.g., public safety, healthcare).

In cybersecurity, for example, customers’ largest line items are typically EDR, firewall, and SASE. Each of these spend categories has become the core product of major cybersecurity platforms, including CrowdStrike, Palo Alto Networks, and Zscaler.

Or consider Figma, which took a platform approach to collaborative design. The company eventually supplanted an entire suite of tools previously used for designing, iterating on, and storing creative assets. Today, Figma offers a suite of products that act as corollaries for everything from Adobe Illustrator, Google Drive, and Dropbox, to prototyping tools like Framer and version control solutions like Abstract.

IYKYK: mission-critical status shows up in two key metrics: gross dollar retention (GDR) and average contract values (ACVs).

- Gross dollar retention captures the amount of revenue you keep from your existing customer base, calculated as beginning ARR net of churn and downgrades, divided by beginning ARR. By dint of being market leaders, platforms often store important data and integrate with other systems, which means customers rarely churn unless they go out of business. For most platforms, this number is above 95% and often above 97%.

- Platform companies are typically the largest line item for a customer in a specific category. While this differs for customer segments, we’ve found most platforms have ACVs of at least $100K in their mid-market and enterprise business. This mission criticality also gives platform companies strong pricing power. Platforms are usually purchased in spite of their high relative pricing, not for being the cheapest alternative.

Of course, these benchmarks shift based on your end market. Platform companies like Shopify and HubSpot would reasonably see lower GDR and ACVs given that they focus on SMBs, but the underlying principle holds.

Market leadership in core market

The most important advantage of being a platform company is winning trust. In order to convince customers to buy multiple products from you over multiple years, your customers need to trust that you’re building the absolute best product available today and will continue to out-innovate the competition. Nobody wants to invest millions of dollars and years of time into a solution only to have to reverse course years later when something better hits the market.

Market leadership also creates a virtuous cycle with the broader ecosystem. Integrators, consultants, and third-party developers all build their businesses around the winner, which makes your platform even stickier for customers. You’re also able to tap into many of the classic benefits within enterprise sales: reference customers within key verticals, scoring at the top right of a Gartner Magic Quadrant, or annual customer conferences.

Market leadership also gives platforms a huge distribution advantage. When customers have a new tech need, they’d usually rather buy from their trusted platform partners than look for a new vendor. Market leaders have a strong base of reference customers and enterprise brand recognition (often in research reports from analysts like Gartner and Forrester), which helps platforms to more efficiently attract, land, and expand new customers.

Salesforce is a classic example. They have over 9,000 pre-built and customizable applications in their AppExchange, independent Salesforce certified consultants generate revenue north of $20B1 per year, and their Dreamforce event in San Francisco consistently draws over 40K attendees.

MongoDB is another. The platform evolved from a developer-friendly NoSQL store into a general purpose, enterprise-focused data platform with the introduction of its fully managed multi-cloud database, Atlas. Now, when customers have net-new needs (e.g., search, recommendations via vector similarity), they typically opt to turn on another Atlas capability instead of onboarding a new, more niche service. MongoDB has also consistently innovated and stayed ahead of the curve, earning its spot as a leader in Gartner and Forrester reports.

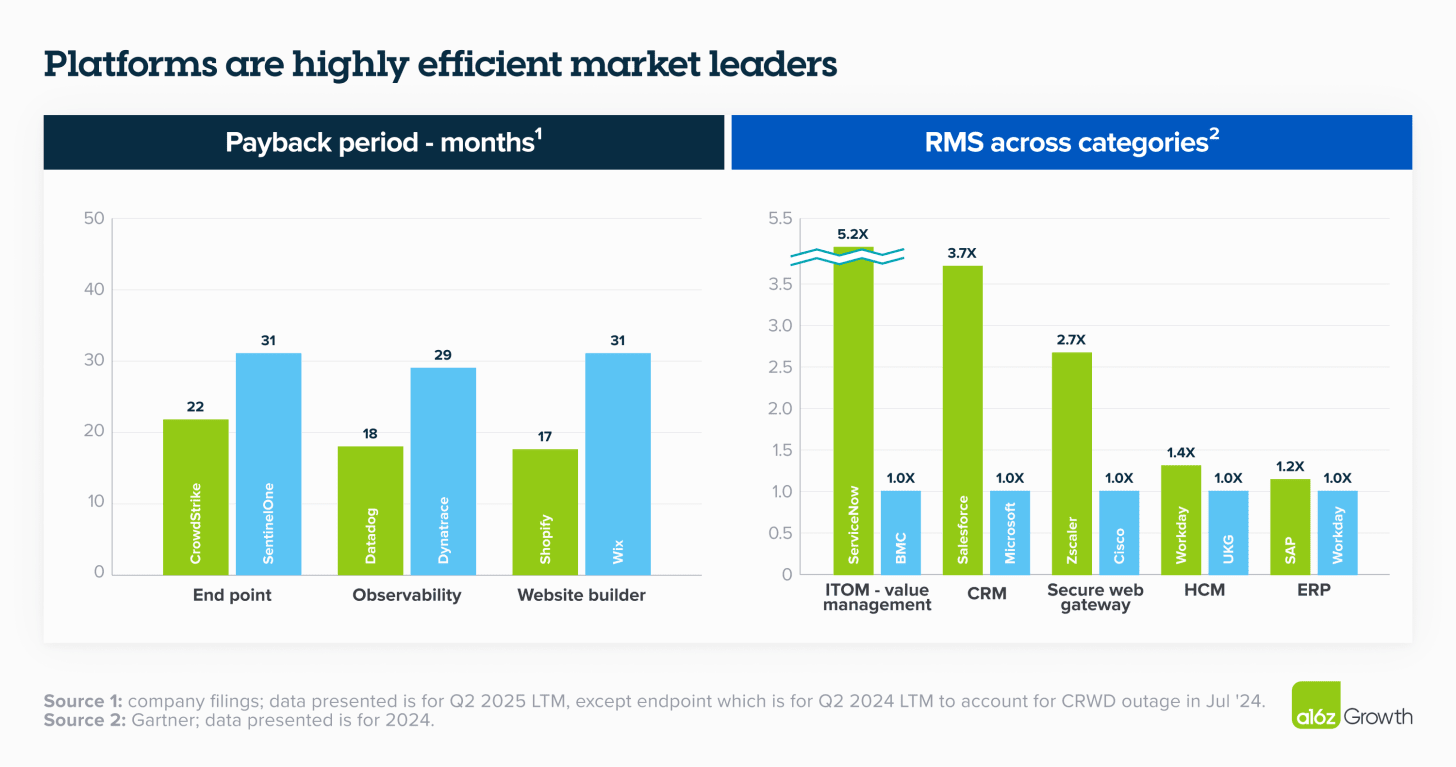

IYKYK: market leadership shows up in your relative market share (RMS) and CAC payback periods.

- When a majority of customers are confident about investing in a given platform, this shows up in the platform’s RMS, which is a company’s revenue divided by the revenue of their largest competitor. If this metric is >1.0x you are the market leader, and the higher this metric the better competitive position you have. The most dominant companies have market share >2.5x+ in horizontal markets at maturity.

- Market leadership makes distribution much more efficient, which shows up in shorter CAC paybacks than competitors, or the time it takes to recoup S&M expenses with new gross profit dollars. The best enterprise platforms typically have sub-24 or even sub-18 month paybacks.

Increasing returns to scale

Because SaaS platforms can continuously improve their offerings by incorporating real-time feedback and usage, scale translates directly into a better product. As the customer base grows, new insights accelerate development, which enhances the product for both existing and future users.

These increasing returns to scale unlock network effects: value created for one customer often benefits the entire base. In cybersecurity, a unified threat graph means that an attack on one company strengthens defenses for all. In HCM, broader participation improves compensation and benefits benchmarks, which allows customers to make more data-driven HR decisions.

These compounding benefits make it easy for platforms to identify and extend into logically adjacent capabilities, or “modules,” that reinforce the whole. Unlike the “suites” of the on-prem era that bundled related but standalone products like Excel and PowerPoint, modules are features sold to the same buyer that build on the core product and share data, workflows, and context. This is also why extensibility is so important: if you don’t build that way from the beginning, your customers won’t be able to adopt your follow-on point solution products, no matter how attractive they might be in a growing product suite. Enterprise customers have to strike out every reason to say “no” before they can start thinking about reasons to say “yes.”

Salesforce illustrates this well: Sales Cloud, Service Cloud, and Marketing Cloud all serve the CRO/CMO, but because they share the same customer record, a support ticket in Service Cloud can automatically surface the customer’s purchase history from Sales Cloud.

Atlassian is another good example. A Jira ticket can be linked to a code commit in Bitbucket and documented in Confluence, multiplying the usefulness of each tool. Each module compounds the company’s value, deepens customer reliance, and strengthens its competitive moat.

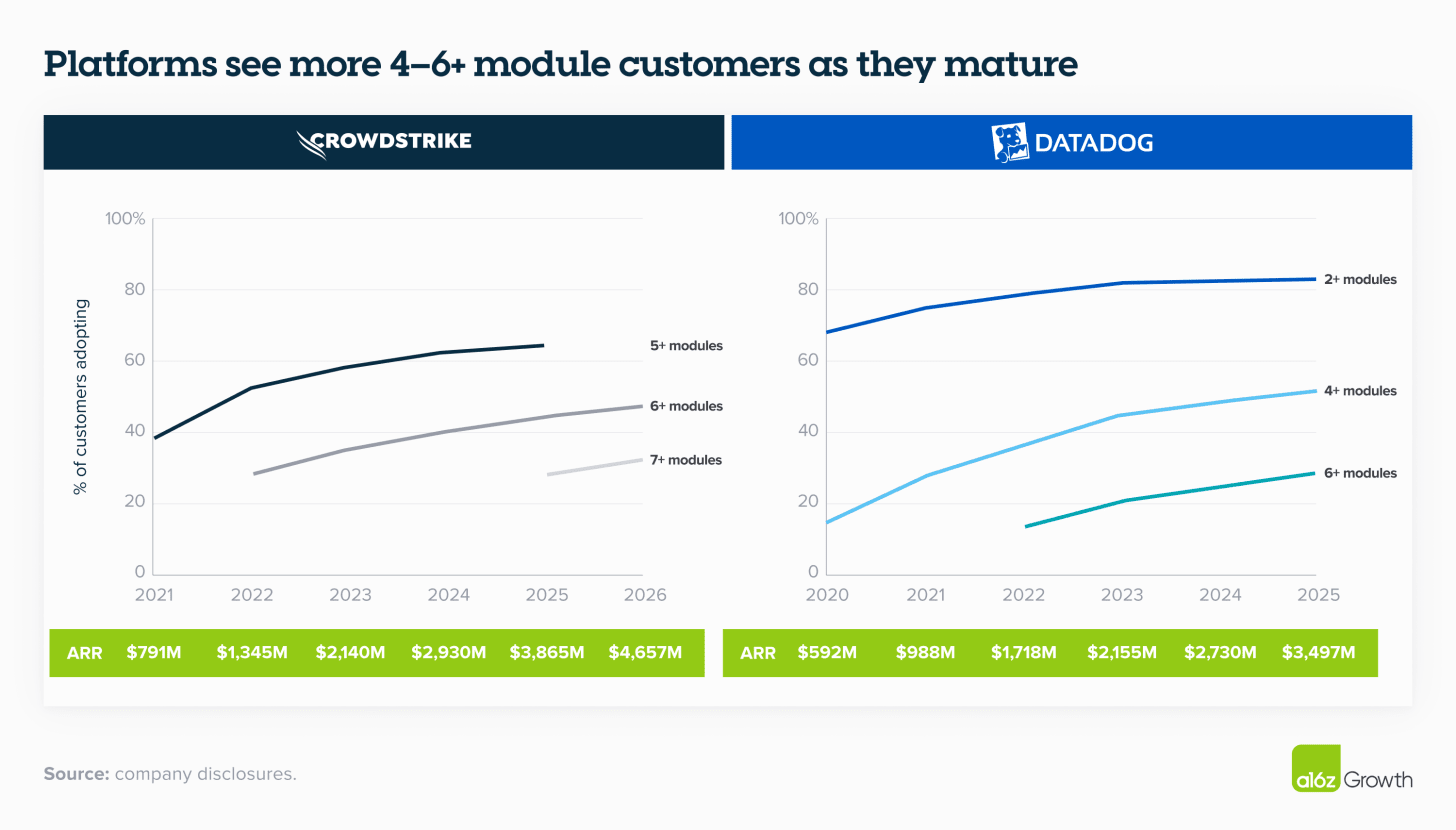

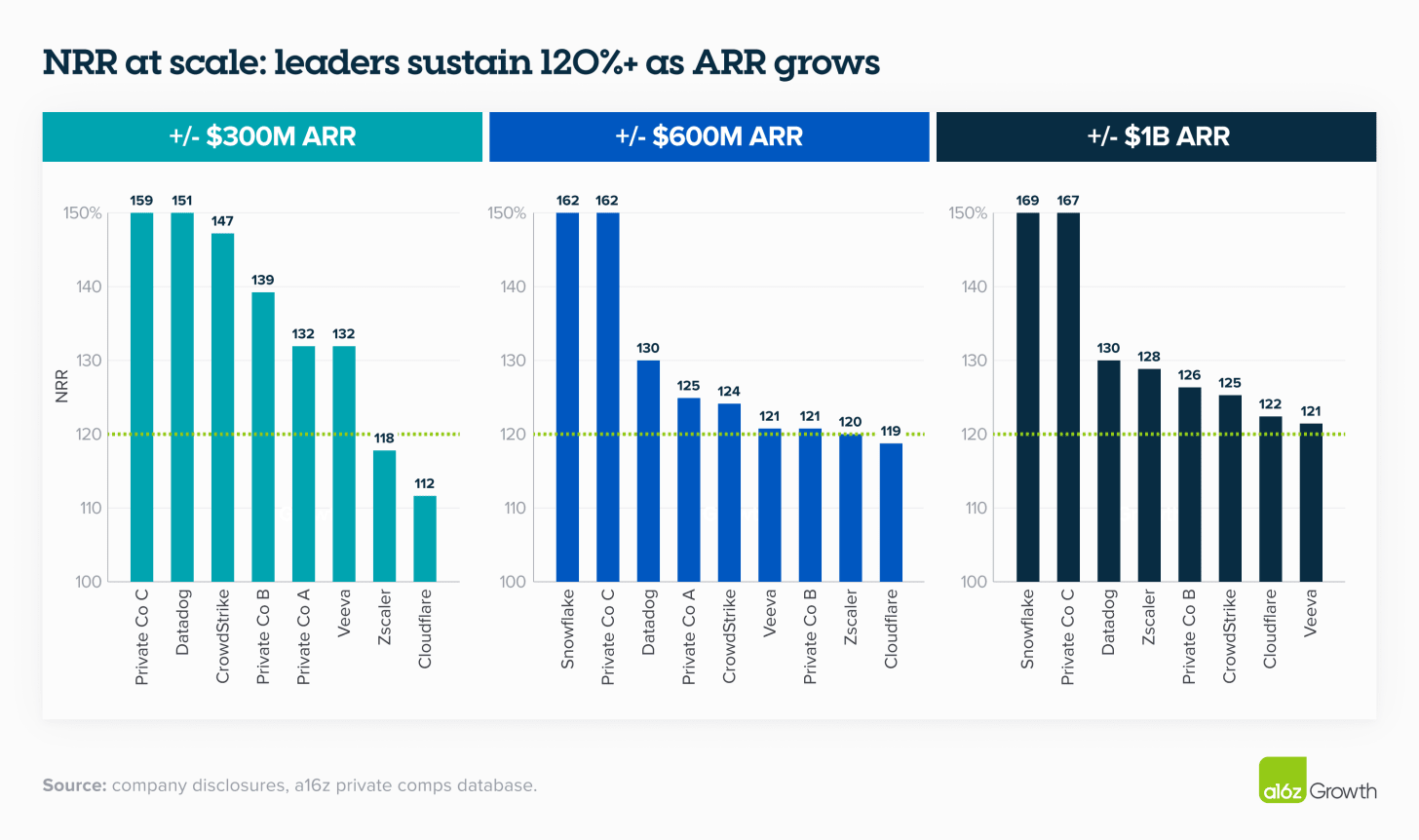

IYKYK: increasing returns to scale show up in multi-module adoption and net revenue retention (NRR).

- Software companies are increasingly reporting how many customers adopt multiple product modules, typically tracking adoption of 4–6 modules. The ideal adoption rate across modules depends on scale, but we think 40–50% of customers using 4+ modules is a strong indicator of success when you’re around $1B of ARR.

- As customers purchase more modules or buy new products, true platforms maintain strong NRR. Best-in-class net retention depends on company scale, but we find this metric is often >120% for platforms under $1B and >110% for platforms over $1B of ARR.

Expanding TAM

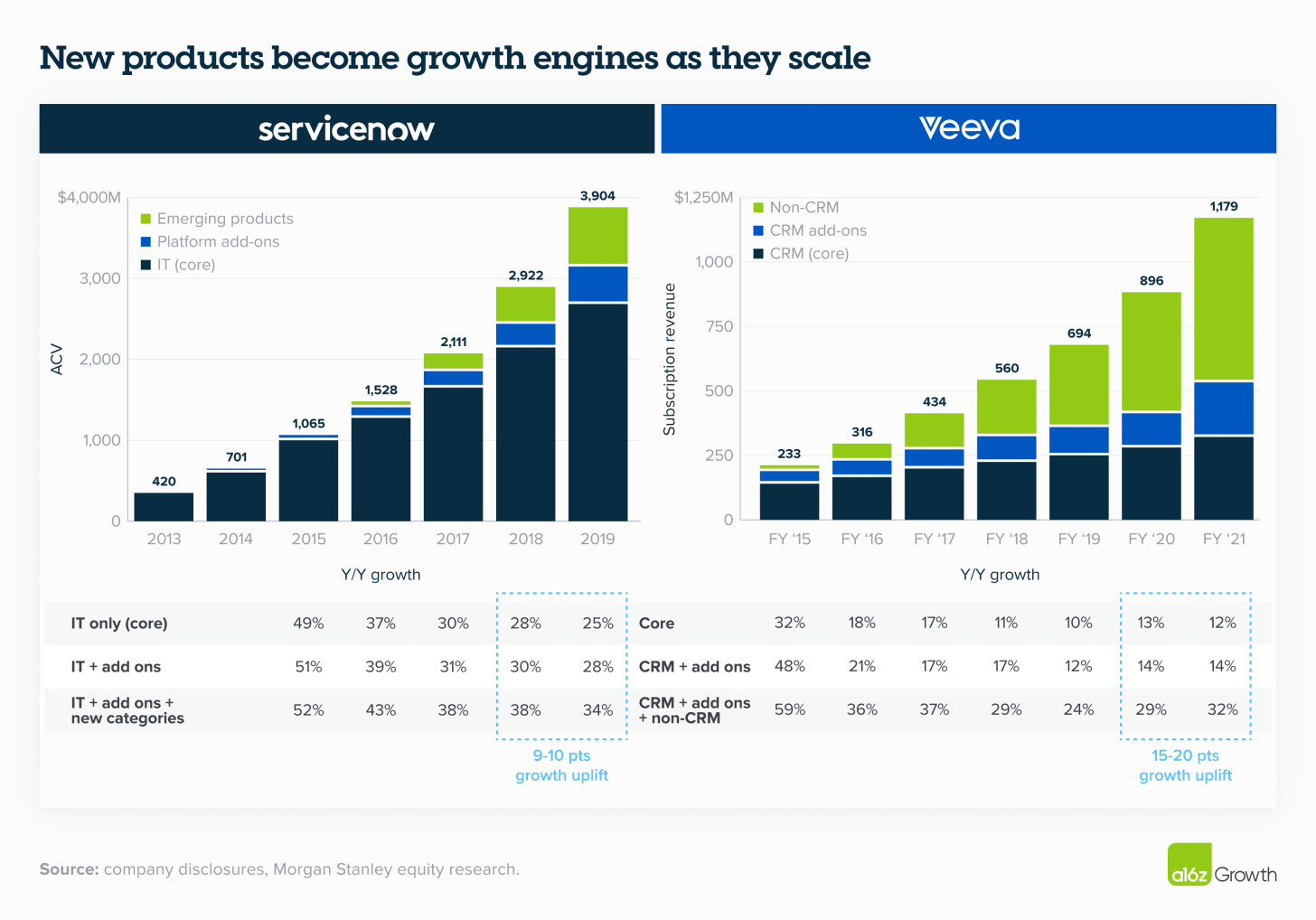

While new modules can make existing products more valuable to customers, most platforms have a limit to how large a company they can support, regardless of how many modules they build. We’ve found that once companies reach closer to $2B ARR, it’s difficult to sustain 30%+ growth rates in their core product. At this point, they typically have to launch a new product category—typically selling into a different but related buyer—in order to sustain their high growth rate and unlock a larger TAM.

Platforms’ distribution advantage and customer love give them a major leg up in whatever market they choose for their second act. Most customers are ecstatic when platform companies move across categories, since platforms are already a trusted system of record within their organizations.

Databricks, for example, began as a platform for big data analytics and machine learning that sold primarily to data scientists and engineers. Since then, however, it leveraged its strong reputation in unified analytics to expand into adjacent product categories like data warehousing. With the launch of Databricks SQL, the company successfully targeted new, but related, buyers within enterprises and broadened its reach beyond traditional data engineering and AI—and built a massive business.

Or look at ServiceNow. The company began as an IT service management (ITSM) platform, selling primarily to CIOs and IT leaders. Over time, ServiceNow hit a limit in ITSM growth, so it leveraged its distribution strength and reputation for workflow automation to expand into adjacent product categories like HR Service Delivery, Customer Service Management, and Security Operations. Each new product targeted new but related buyers within the company, like the CHRO, COO, CISO.

IYKYK: TAM expansion shows up in non-core product growth.

- As they scale, a significant portion of platform companies’ revenue comes from additional products. While this varies from company to company, we generally see clear evidence of second product success before the core product is growing <30%.

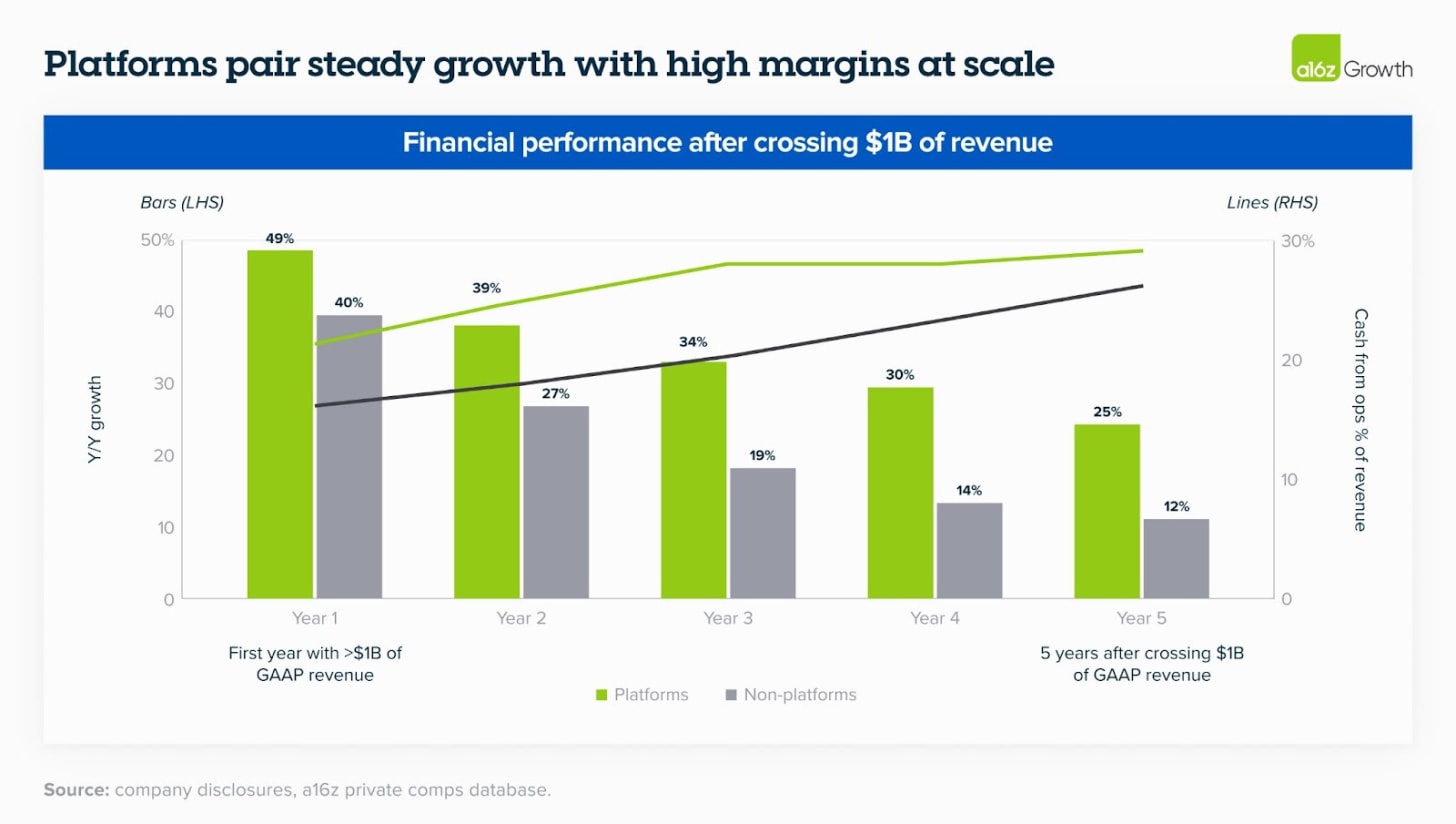

Compounding growth and durable margins at scale

Because platform companies have all of the attributes we’ve described above, they can invest at very high rates of return across product development and sales and marketing. This, in turn, helps enterprise platforms grow faster, and for longer, and with better margins than anyone would anticipate. Companies can call themselves platforms all they want, but ultimately, the proof is in the P&L.

How platform companies might evolve in the AI era

The great platforms of the past 20 years were built on top of a commoditized cloud infrastructure, which directed most of the value to the application layer. Though we’re very early, we’re seeing signs that a similar dynamic will play out in AI, and we think platform advantages might compound even further. Here’s what we see so far.

Owning the workflow beats owning the model. We’ve seen a ton of value in understanding the specific workflows for a given AI app use case, and that’s only becoming more important as agents complete more tasks end-to-end. In the same way a new hire needs to learn context and processes at a company, AI needs to translate raw business intelligence into real business outcomes. As products shift from assistants to agents, platforms will package: (1) orchestration and guardrails, (2) a memory layer for company context, (3) integrations/tools to take action, and (4) evaluation loops to prove the task is done.

AI expands the reachable workflows in a single platform by lowering the marginal effort to automate new workflows and tapping into unstructured data. Historically, platforms hit natural boundaries defined by structured data and deterministic workflows. You could automate invoice processing if the data lived in defined fields, but not contract review buried in PDFs. AI slips these constraints. AI companies can now reach into unstructured data like emails, documents, and video calls and make it actionable within their core workflows, which means they can feasibly capture more wallet share from customers.

AI software development tools shorten development cycles. The implications here go beyond just shipping features faster. When AI coding assistants can generate boilerplate, write tests, and handle integrations in minutes instead of weeks, platforms can experiment with adjacent modules at near-zero marginal cost. This fundamentally changes the build vs. buy calculus for platform expansion—something we’ll touch on in later posts.

Moreover, when your engineering team can prototype a new workflow automation in days and iterate based on real customer usage, you can capture value that would have traditionally leaked to point solutions. New products and new modules could also start arriving earlier in company life, which could lead to quickly compounding advantages for leading platforms as they scale.

Increasing returns to scale could intensify. The more customer data companies have, the more those companies can fine-tune a model for a specific use case or improve task performance and completion across customers. Context compounds across use cases inside an account, too. As Cursor learns how your engineering org reviews code, names services, and ships, for instance, it makes Cursor perform better for everyone in that company and cheaper to expand across teams.

So: while the anatomy we’ve outlined—mission criticality, market leadership, increasing returns to scale, TAM expansion, and compounding growth at scale—can help us understand today’s winners, it also outlines where and how enterprise AI platforms might overperform in the future.

For founders, then, the goalposts for greatness don’t change. The question is: who will get there first?