In 2011, Palantir did something funny. They took their solutions engineers and integration engineers—typically among the lower-status roles in any engineering org—and gave them a new title: forward-deployed engineer. They even called them “Deltas,” like Delta Force. It sounded ridiculous, and it worked brilliantly.

It seems like Palantir understood two things. First, they understood that these employees were undervalued: they were critical to customer success and business reputation, but traditionally treated as replaceable help. Second, they understood something about titles, which we’ll call title arbitrage: the fact that titles can be an effective way of meme-ing into existence the change you want to see in the world.

What is title arbitrage?

Title arbitrage means creating new roles to signify new powers that are emerging within the organization, and therefore, new capabilities of the organization itself.

Like it or not, a lot of professional life is judging people by their titles. The CEO is probably the most important person in the room, and the COO, CTO or CFO is probably the second-most (depending on the company). Titles are useful. They tell us something about the work product of the person: the Vice President of Manufacturing is, well, the guy in charge of manufacturing. Titles confer legitimacy.

Titles are also about legible organizational capacity. Companies are these weird things where many people get together to take actions in coordinated ways that add up to be much more than what any individual person could do. And in order for that coordination to be effective, you need a shared agreement over what roles speak to what organizational capacities.

But here’s the thing about organizational capacity: it changes. The world changes, and different skills and competencies become more useful or less useful. In 1770, cavalry officers needed to be able to ride horses; but by 1970, the “cavalry” meant helicopters. So the distribution of power, of leverage, shifts. And eventually titles, which are supposed to signify power, have to shift with them.

And the people who figure this out earlier than others, the ones who know where the wind is blowing, can reap enormous benefits.

By recasting the role, like Walmart did with “Greeter” or Disney with “Imagineer”, Palantir effectively bet: “deep software integrations with huge enterprises and governments will be really important in the future. This work needs to have its profile raised accordingly.” And they were right. The FDE role attracted high-agency, high-EQ engineers who might otherwise have seen client-facing work as unappreciated. The title gave the work prestige—and Palantir got a hiring moat.

Some examples

Once you start to look, you see title arbitrage everywhere.

There’s no better example than with the people who make every technical company run—coders. First, coders were relatively unimportant, and they were called “IT.” But IT conjures up cubicles, Dilbert, Office Space. But as software grew in business importance, the names of roles changed to become “programmers,” which is a bit cooler, but still had a sort of nerdy vibe. And then in the 2000s/2010s, once software truly started to eat the world, coders became “software engineers”! They’re big thinkers, not just code monkeys, but engineers building transformative technology like the people who build bridges and airplanes. The names of these roles continually changed as the status of the work they were doing rose in business importance.

In the world of data, the progression went from “clerk” to “data entry” to “data scientist” to, now, “machine learning engineer”—each shift tracking the rising strategic value of being the person who works with data. It used to be a low-status job; now it’s one of the most important roles in any serious org. The same with the lowly system administrator: Google coined the term “Site Reliability Engineer” to signal that keeping systems running was as intellectually demanding as building them in the first place.

The same thing happened with marketing. Dropbox, Facebook and others made “growth hacker” and then “Head of Growth” legitimate titles, signaling that marketing had become a part of the product org: engineering-adjacent and experiment-driven. “Social media manager” evolved into “Head of Community” or “Head of Ecosystem”—managing a Twitter account became owning the relationship with an entire ecosystem.

In design, “graphic designer” became “UX designer” became “product designer” became “design engineer”—each step capturing more ownership over the end product. In operations, “secretary” became “executive assistant” became “chief of staff” or “head of ops”—a deliberately ambiguous title, sitting somewhere between scheduling meetings and shaping strategy.

New titles can signal business model shifts

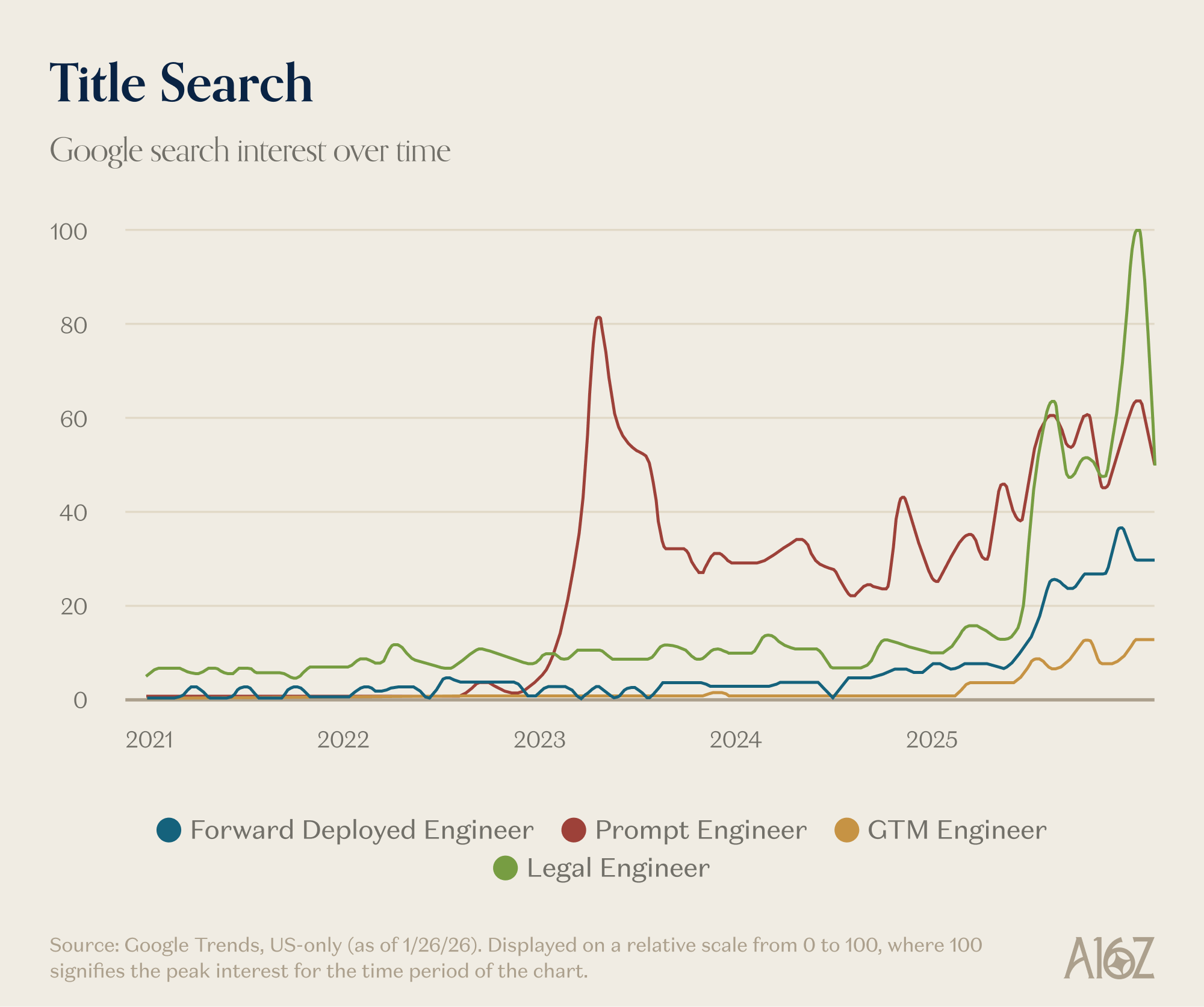

What Clay is doing now with “GTM engineer”, or what Harvey is doing with “legal engineer” goes genuinely beyond just marketing; it describes work that genuinely didn’t exist five years ago.

But here’s the question skeptics will ask: isn’t this just status inflation? What differentiates this genuine phenomenon compared to title inflation – where titles run a Red Queen’s Race of escalating fake prestige, simply to keep in place within a labor market where inflation is commonplace? Or more opaque resumé padding, where insiders confer elaborate titles on each other to appear opaquely impressive to outsiders? (Like “Lead Editor” in a law journal, which can counterintuitively mean the most junior contributor?)

The difference is whether there’s a real, underlying shift in the work. “Prompt engineer,” which Scale AI pioneered, already feels dated, because the work it described—writing prompts—turned out to be a feature of every job rather than a job unto itself. The title ran ahead of reality. But “GTM engineer” or “legal engineer” describe genuinely new combinations of skills that companies actually need.

The test is this: does the new title describe work that would have been unrecognizable five years ago? If yes, you might be onto something. If you’re just renaming “marketing coordinator” to “growth strategist,” but keeping all the responsibilities the same, then you’re not doing title arbitrage: you’re doing title inflation, and the best people will be able to tell the difference.

And we’re now seeing the emergence of titles in other industries caught in AI transformation. Watch for more of these in the coming years: “prompt engineer” evolving into “AI applications engineer” or “model behavior specialist.” “Compliance officer” becoming “AI governance lead.” “Analyst” in consulting and finance becoming “intelligence engineer” for those building AI-augmented research workflows.

These are from Google Trends, so take it with a grain of salt, but what really stands out here is the recent surge for “Legal Engineer.” Harvey’s really been pulling the SEO lever, it seems!

The main utility of this for the company is also that it signals to other companies, “you should care what this person says.” A name is a pointer. It points to something you should care about. A new name gives people permission to care about this new thing.

Early adopting lawyers, afraid of AI, can now self-identify as legal engineers. Lawyers know a lot about contract redlines and mitigating risk, but not much about workflow automation or context graphs. But legal engineers know both. The new title gives early-adopting legal professionals permission to learn to use AI from a place of empowerment, instead of fear.

People transform companies, more than products do

This points to something important about how AI actually transforms organizations. When you look at a regular company and ask “how is AI going to change this business,” the stock answer is “all of these interfaces are going to get smarter,” or “x tools are going to change.” But that’s also the wrong answer. The much better answer is this: specific people, often young people, are going to use AI to have dramatically more leverage to solve problems inside the org, and you are going to be shocked by how effective they are. The imperative for every CEO or org leader is this: identify them, listen to them, and promote them.

There’s a classic pattern in large companies whenever they adopt groundbreaking new software, like when Airbus adopts Palantir. All the smart young people come out of the woodwork and use the new software to improve things. New technology shifts the balance of power in the organization, and it’s always the ambitious young people who realize this first. This is where new titles can be a genuine indicator of people creating new jobs for themselves out of newfound leverage.

And a newly named job title has incredibly strong PMF for these kinds of people. It bestows social legitimacy on what they’re doing. “Oh, great, Alex, you love this tool—why don’t you be our legal engineer”?

And if your company is an early mover on this, you hold the power—and if you’re the first mover, you own it: you define the entire job.

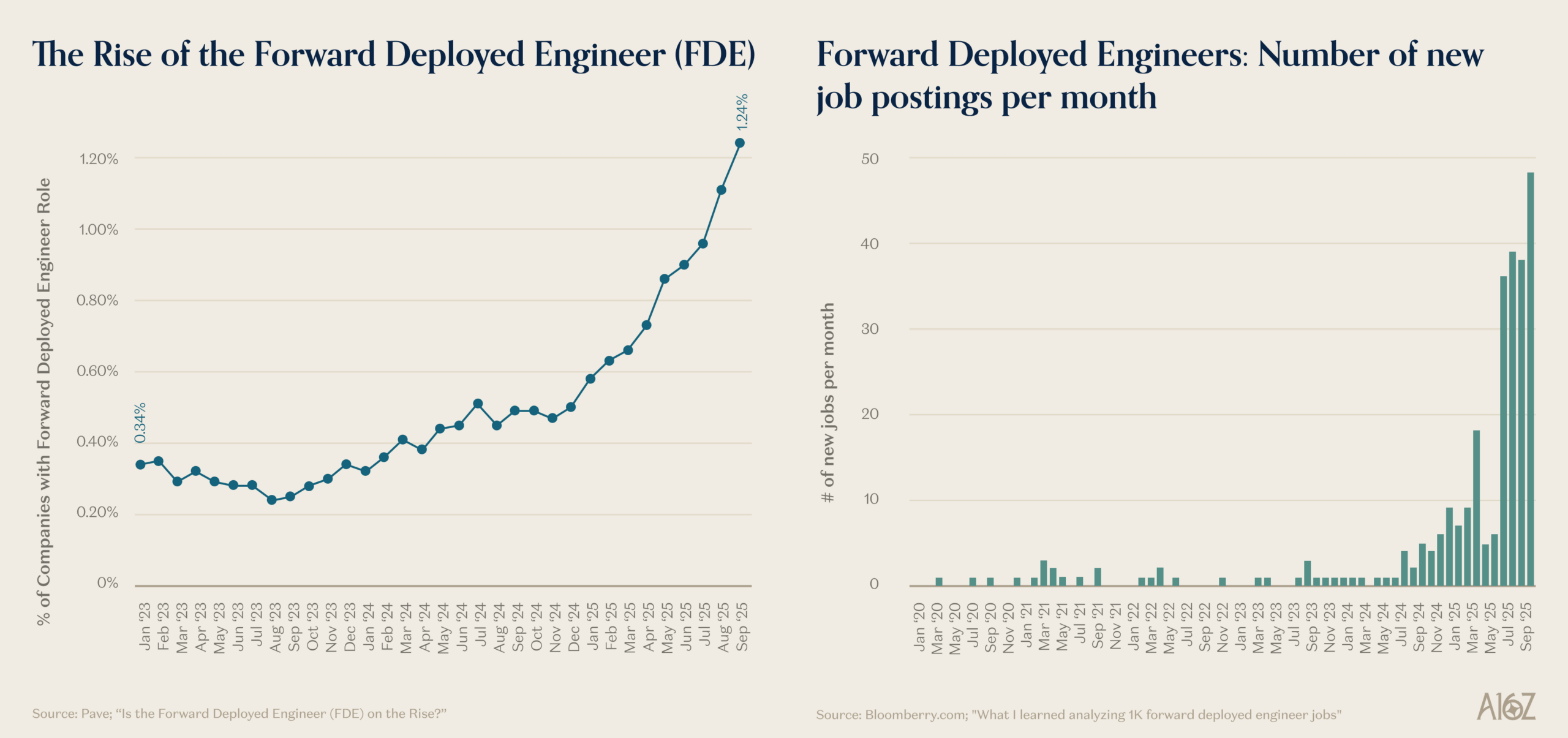

Today, there are hundreds of companies hiring FDEs. But Palantir owns FDE. Any time you think of the FDE term, you think of Palantir. Because they moved first to own this term, they have incredible mindshare when it comes to hiring. When a talented engineer considers client-facing technical work, Palantir is the default comparison—not because they’re necessarily the best place to do the job, but because they named the job.

So if AI is transforming your industry, work out what the jobs of the future will be. Coin a new title. Plant a flag. Winning attention is one of the hardest challenges for businesses today. If your market associates a winning concept with your company, you are much closer to winning yourself.