When we think about professionals buying software – from individual developers up through huge enterprises – it’s often not enough for the product to be good and useful. You have to convince your prospective users of your credibility and of your vision of the future: your technical approach, the tradeoffs you embrace, the stack you’re betting on, must be something they want to commit to. To do this, you need to convey legitimacy: that you’ve earned the right to be taken seriously.

Product legitimacy and “kingmaking” have a storied history in Silicon Valley. We sat down with Steven Sinofsky, who has seen it all, to get the story:

- The 60s and 70s: how Special Interest Groups and User Groups were the test for being taken seriously.

- The 80s and 90s: the rise of magazines as kingmakers, and why you’d spend months trying to get PC Magazine Editor’s Choice or a good review from Walt Mossberg.

- The legitimacy of early influential users, who’d try your product on the job if no one would stop them, the same way with early PCs as with early ChatGPT.

- Venture Capital: the “Legitimacy bridge loan” that helps you get phone calls returned.

Here’s Steven (edited from our conversation for length and clarity):

Special Interest Groups: the Github of the 60s and 70s

Let’s begin in the mainframe era of the 1960s and 70s. Computers themselves were these flakey things that very few people used – and when you did, you’d use whatever computer your company had. And nobody sold software – software was free, but you had to acquire it somehow. So what started were these things called SIGs, Special Interest Groups, which were formed around a particular programming language or batch operating system.

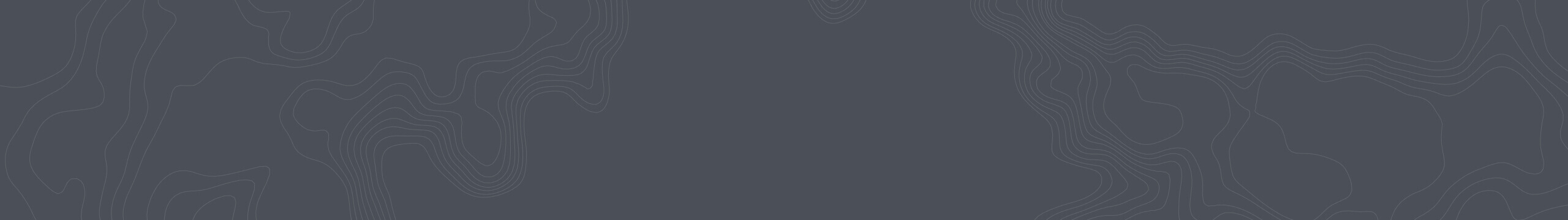

These SIGs would meet in person – there were many in the Valley, or in Boston. I grew up in Orlando, and there were a lot of SIGs there because of the aerospace industry. I would go when I was in high school, and there would be all these grownups there with jobs like launching rockets. It was cool.

The first defacto industry-wide legitimacy signal in those days were the RFCs for the early internet. Every time someone wanted to propose a new standard, they’d write it up in this properly formatted document called an RFC, a Request For Comment. And only certain people, within the right SIGs, had the legitimacy to endorse for a proposal to be taken seriously. If you needed something in networking, that’s Bob Metcalf, for example.

Eventually these SIGs became a bit more rebellious – more like clubs. They evolved into what we called User Groups, who would send out newsletters, and people would get together in-person because that was how you got software. If you wanted, say, a file management utility for the Osborne, you went to the Osborne user group and the main organizer / “head librarian” would help you copy over that software onto your blank floppies, and then you knew you had the legitimate version of that piece of software.

These user groups became the locus of very important discussion. It was on the Home Brew Group newsletter where Bill Gates published his famous Open Letter to Hobbyists, where he essentially told them, “Hey you guys are stealing all of the software. You should pay for it, otherwise there won’t be software companies.”

Bill Gates understood how important these user groups were, and how important they were as a source of legitimacy. Even though he was running Microsoft, a lot of people didn’t know who he was yet, or perhaps they had heard of him but didn’t know what he thought. So Bill would write these long articles in their newsletters on, “This is what an operating system is”, or Paul Allen would write about the mouse, or the graphical user interface. And that’s how computer people really got to know us and what we were about, and those were the people that mattered.

Microsoft became legitimate, over time, because we showed up. These were deeply technical audiences; most of the exchange would be Q and A. And then we’d head back to Microsoft and say, “Okay everybody, here is the customer feedback.” And that was that.

The other neat thing was that the exchange was bidirectional. It wasn’t only us talking about Windows: the meetings would be full of people who’d written Windows applications, and they wanted Microsoft to know about it and talk about it. That’s how they gained legitimacy with us, which was equally important in the grand scheme of things.

It remained this way for longer than you might expect. For example, in 1993, I had done the Windows graphical interfaces for C++, which was new; no one was using it yet. So I just got inundated with questions, and my ability to answer them was what gave Windows any credibility with these people. This was the ground game of legitimacy acquisition.

Publishers become Kingmakers

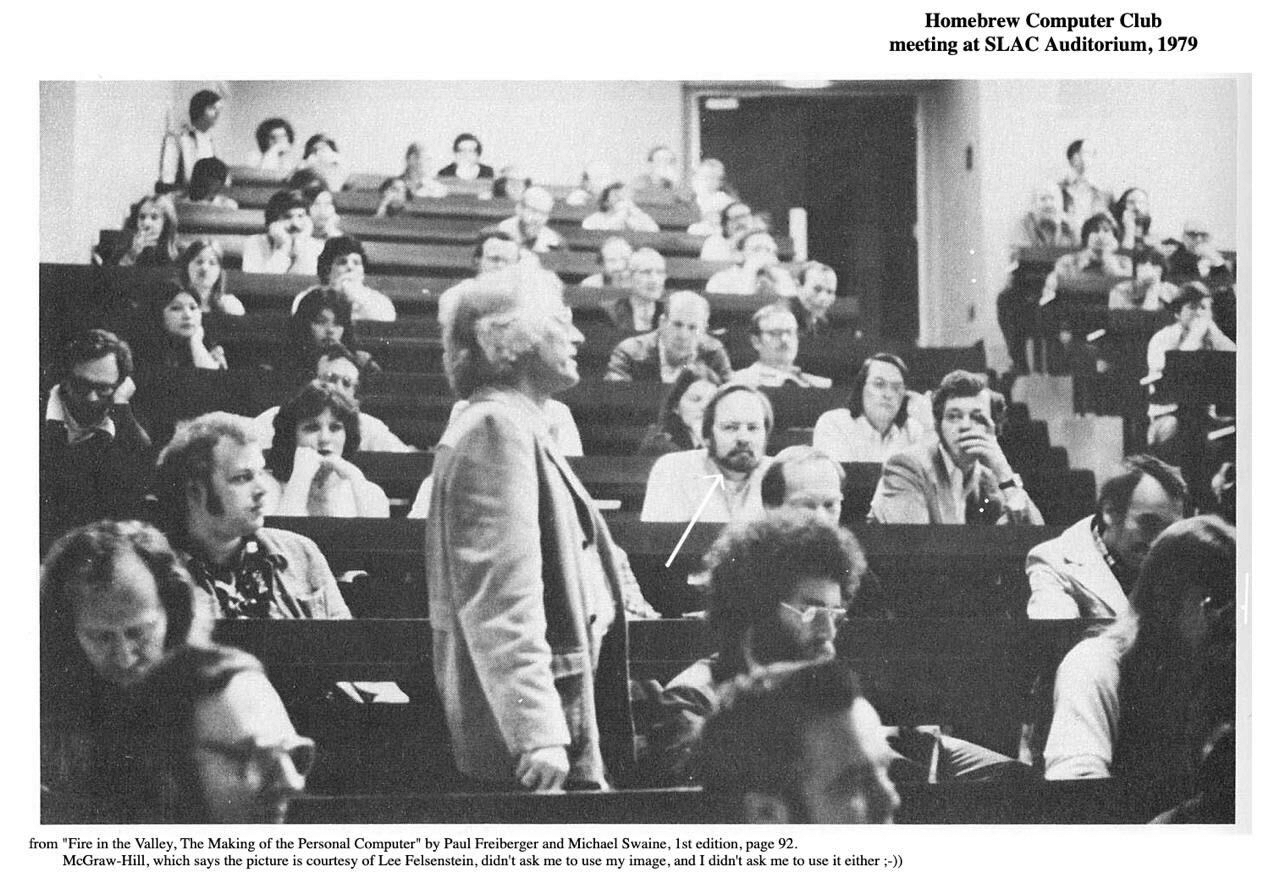

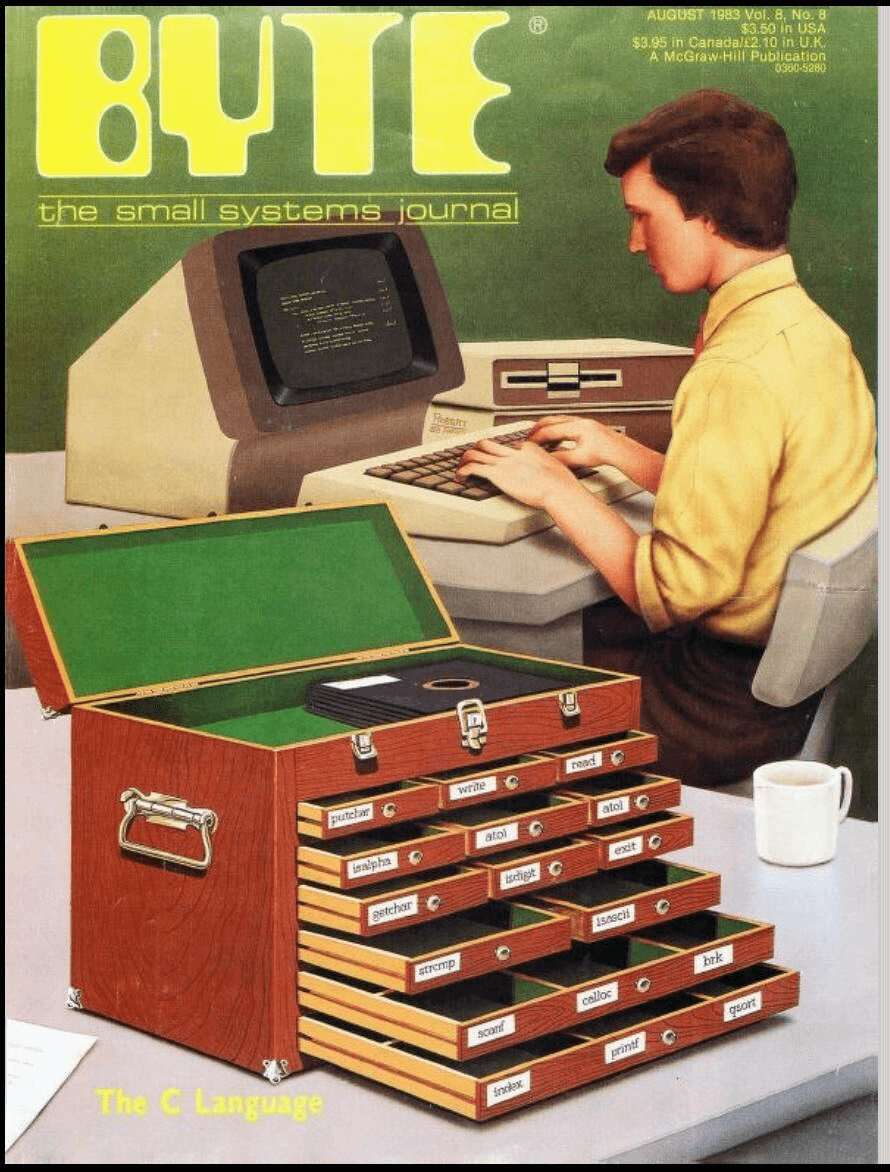

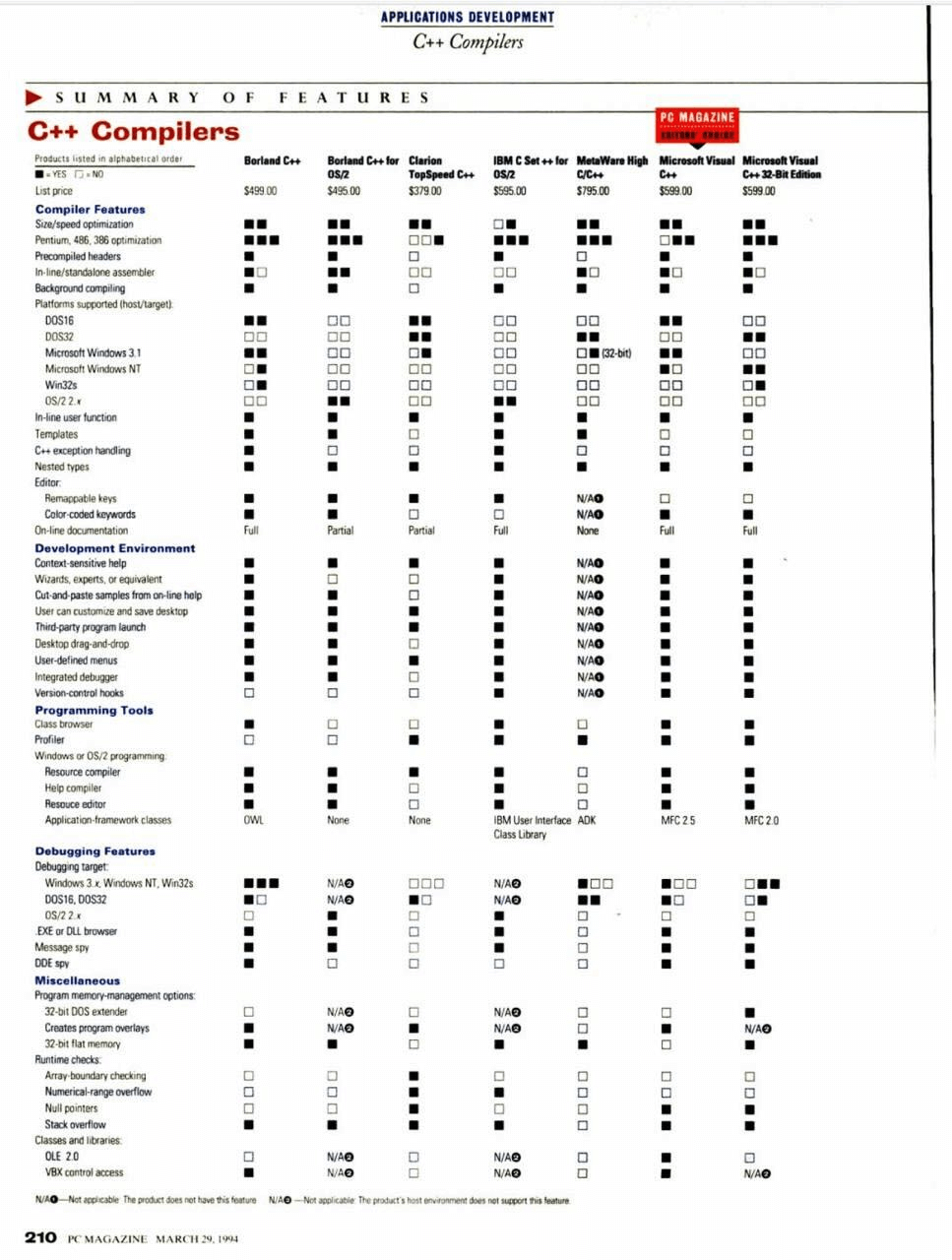

PC Magazine launched in 1981, and that ended up changing everything. They decided that they weren’t just going to review the things programmers cared about, like Basic, C, Fortran and Pascal; they were also going to cover Word Processors, Spreadsheets, Databases, and even whole computer systems and printers. They wanted to cover the entire experience of being a PC consumer, and would start doing cross-sectional reviews of, for example, all 30 Word Processors that were on the market.

From this point forward, the job of bringing a product to market had to include lobbying campaigns, to make sure your product would be covered faithfully. It wasn’t just writing to the newsletters and doing in-person Q&A with other computer people.

So, if we were launching software like my C++ compiler, what would literally happen was, we would fly to Boston, rent a car, and then drive to New Hampshire to meet Byte Magazine. And Byte had an enormous building there, which was originally built for bovine veterinarians – you’d get into the elevator and it would be a giant two-sided elevator meant for cows. So you’d enter into this huge building, and there was this colossal floor with every microcomputer, and every printer. And then there were dozens of people that would go test every piece of software, on our compiler and then our competitor’s, and then another’s and they’d use all kinds of evals.

The eval process was an intense form of legitimacy-making. If you won a review, like PC Magazine Editor’s Choice, it was such a sign of legitimacy that you’d go to Comdex, the big computer show in Las Vegas, and they’d do a black tie banquet at Caesar’s Palace, like the Academy Awards of computing. You’d get up and accept the award; you’d walk around all night with a trophy. We had a trophy case at Microsoft with these awards on them. And afterwards, you’d get to put “PC Magazine Editor’s Choice” on the box copy of the software.

Over time, the legitimacy-making moved into the newspapers, with Walt Mossberg really leading the charge. He had been a seasoned reporter, who’d covered wars, and the World Bank; and then one day he started a computer column. The idea was to hold the product-makers’ feet to the fire, ultimately to make those products better. So, all of the effort we’d used to spend going to Nashua, New Hampshire, we’d spend time with these five or six writers. I can’t count how many times I flew out to Washington DC to see Walt, or see David Pogue down here, because they just became everything.

The peak of print influence was the launch of the iPhone. So you had these three or four people, whose thumbs up or thumbs down was very important to that product launch. At the time, remember, the Blackberry was what every serious business person used; essentially 100% of people reading the Wall Street Journal had one. And then here came this type-on-glass web browser / music player kind of device. Walt spent a few weeks testing it, calling to ask questions, and, of course, the person on the other end of the phone handling the problems was Steve Jobs. That’s how important Walt was.

We spent so much time on those reviews. I remember when we launched Outlook 97, which was the first version of Outlook. And Walt called the first version of it “Byzantine.” It was crushing. I get sick to my stomach even today thinking about it. The New York Times called the whole release a “Leviathan”, and then the next day I had to smile, go to the executive briefing center, and talk to CIOs from around the world who would ask, “What does the word Leviathan mean? We are an Italian refrigerator company.”

Influential End Users: from PCs to GPT

If you look at what’s happening with AI adoption today inside of big companies, as unprecedented as this might seem, it’s almost exactly the same pattern as what happened with enterprises and PCs.

It starts with a select group of people inside a big company: the people who are curious, and care about how to make the company work better. These are the people who started using PCs way back when, or who started using ChatGPT a few years ago, simply because no one stopped them. And before long, you’d see little crowds of people form around them, saying, “hey, would you look at that, look what he just did!”, and that’s how these things spread.

I first got a word processor in college; I’d sit in my dorm typing papers on my Osborne computer, and people would stop by my room because they’d hear the printer and ask, “What are you doing?” I had to meet with the Dean and explain to him what it was; I was what you’d call an “influential end user.”

This continued into my internship. In 1982, I was an intern working at a huge defence contractor in Orlando, and I had a PC that we’d brought in. Nothing was networked then; you could literally just wheel in a PC on a cart, and no one would stop you. And sure enough, people would crowd into our tiny office and we’d show them how to do things with Lotus 1-2-3, how to use Word Perfect. At some point, a retired General who held a senior position at the company said he wanted a PC, so I’d set one up for him, and wheel it down to the other end of the factory where his office was.

What defined these early PC users was that they were people who were willing to be creative about their job–which is not many people, at first. And this is exactly what happened with the first batch of ChatGPT users. No one stopped you from using it; you just opened it in a browser tab, and suddenly you had this “new kind of computer”, that you could show off doing new kinds of work, in a way that attracted little crowds of people asking what you were doing.

Once Windows 95 came out and everyone started buying PCs and using them at home, the IT departments could no longer let employees just expense PCs on their credit card. This was the moment IT moved out of the back office and into the front office – it wasn’t just hardware and software for influential power users, but also the marketing people and the salespeople.

Once you have legitimacy, you’re selling a story

From this point forward, selling to IT departments really changed again. You had to rely on your product legitimacy, but you couldn’t just tell a story about the product, because you had to tell a story about the future.

Microsoft had an Executive Briefing Center where we would host CIOs all day, and all the Microsoft product people would give talks to convince these buyers that you had a strategy and a master plan. I went to the first one of these meetings, and I remember thinking, “This is the dumbest thing I’ve ever been to.” Because I came in, ready to do a big demo to talk about the product – “Here’s Office 97, it’s great”, and all they wanted to hear about was my Ten Year Plan.

And, here’s the best part, you get rated for your presentation. And I got crappy ratings. Steve Ballmer, who was running the enterprise sales force, told me point blank, “This cannot happen!” This was a hard lesson to learn. Because, as the person who shipped the product, all you can think about is this mountain you just climbed to make that moment, and that demo, and that feature, possible. But all they want to hear about is, “What is Word Processing going to be in 10 years?”

It’s weird to say, but leveraging legitimacy in the business world comes from your ability to sound credible forecasting the future. Once you have heft and legitimacy, your customers implicitly think, “Well, I can’t get fired for buying a vision, if that vision came from Microsoft. That’s not true for a startup – if you bet on Freddy’s Software Startup and their vision doesn’t come true, well that enterprise buyer isn’t going to bet on startups again, end of story. Whereas if Microsoft doesn’t deliver, well the CEO of your company is going to run into Satya at some event like Sun Valley, and say, “You know, my guys really complain about Microsoft”, but that’s really it, because there isn’t another legitimate choice.

Venture Capital: the Legitimacy Bank

Now today, if you’re a startup doing anything related to AI, someone is probably going to talk to you. But that doesn’t mean you have legitimacy in the space you want to sell into. The old rules still apply, in places like legal or medicine. Your AI does not make a doctor or a hospital administrator have time to talk to you about their software. They have legitimacy signals they look for; they’re not just going to try anything.

Now, for a lot of developers and engineers, the paper trail you leave on GitHub is an incredible tool, and in the consumer world we had Product Hunt and other signals. But for a lot of companies that are selling into businesses, getting those critical introductions, or having an executive briefing center like Andreessen Horowitz has, goes a long way. It means you’ve qualified.

And this remains true no matter how much bottoms-up qualification you’ve earned in the technical world. It doesn’t matter how many stars you have on GitHub, if you go sell to a soap company, they’re going to think, “Small company, risk!” Trends come and go; kingmakers like Walt come and go. But the need for legitimacy, in some form or another, is a constant. The more choices people have, the more they will look for legitimacy signals to make that choice.