Editor’s Note: The open source software (OSS) movement has created some of our most important and widely used technologies, including operating systems, web browsers, and databases. Our world would not function, or at least not function as well, without open source software.

While open source has delivered amazing technological innovation, commercial innovation – most recently and notably the rise of software-as-a-service – has been just as vital to the success of the movement. And since open source is by definition software that is free for anyone to use, modify, and distribute, open source businesses have required different models and a different go to market than other kinds of software companies.

Peter Levine has been working with open source as a developer, entrepreneur, and investor for more than thirty years. He recently gave a talk called “Open Source: From Community to Commercialization” (you can download the full presentation here), that drew on his own experiences as well as interviews with dozens of open source experts. Below is a written version of that presentation, in which Peter tracks the rise of open source software and provides a practical, end-to-end framework for turning an open source project into a successful business.

—

Open source started as a fringe activity, but has since become the center of software development. One of my favorite anecdotes from the early days of open source – when it wasn’t yet even called open source, and was just “free software” – is around the Linux/Unix command [~}$ BIFF that informs a user when a new email arrives. The command was named after a hippie’s dog in Berkeley that would run out to bark at the mailman. I love this anecdote because open source was so on the fringes in the early days that an important command was named after a developer’s dog.

I’ve been working with open source for many decades, originally as a developer at MIT’s Project Athena and the Open Software Foundation, then as the CEO of the open source company, XenSource. And for the past 10 years, I’ve been on the boards of a number of companies involved with open source. From developer to board member, I’ve seen the evolution of open source and watched as large companies that have been built on the foundation of open source projects.

I really believe that there has never been a better time to build an open source business. Commercial innovation is essential to the open source movement and here I provide a framework for taking open source products to market.

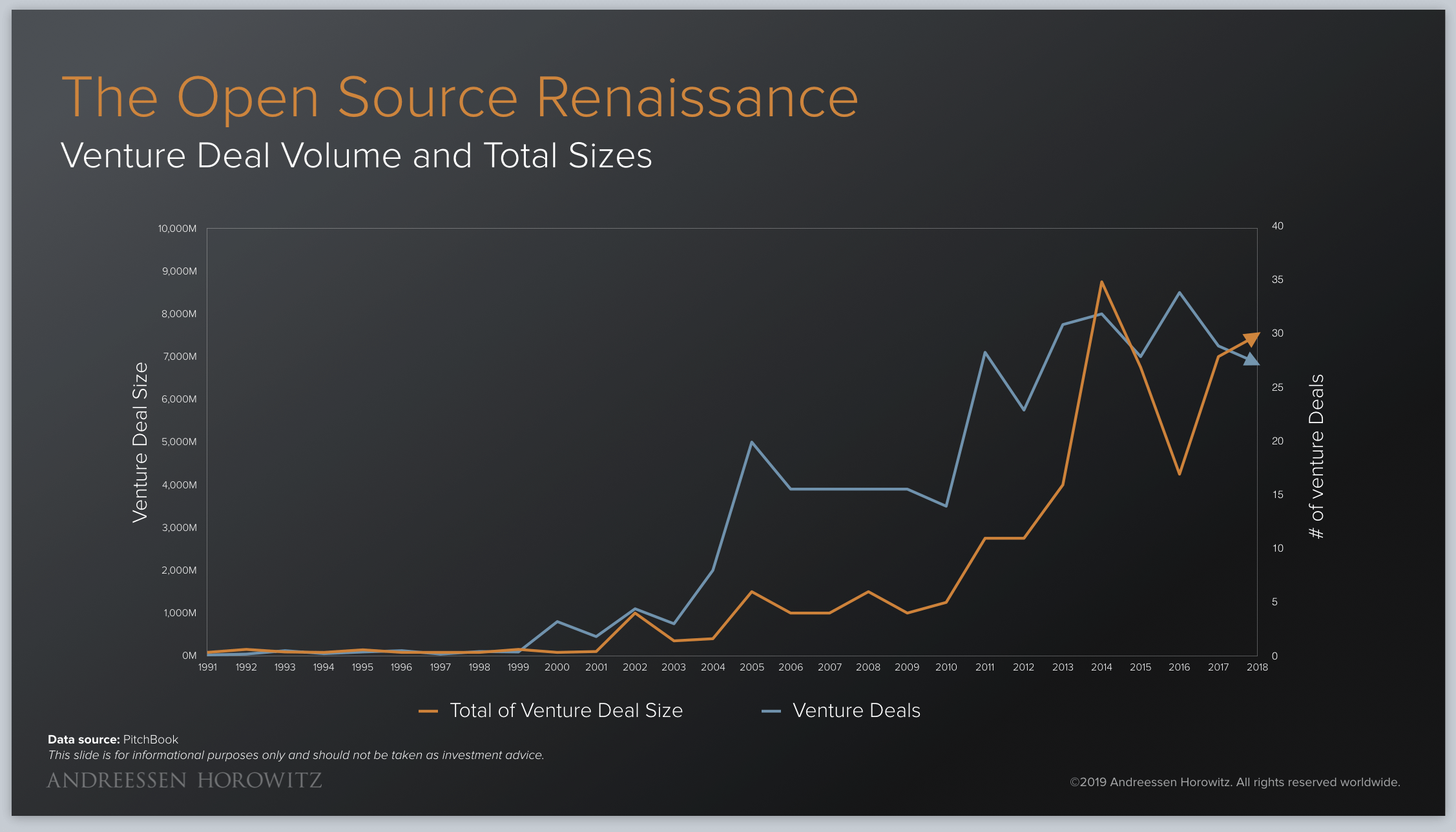

The Open Source Renaissance is Underway

The last 10 years have been a renaissance for open source. The above graph shows the past 30 years, and in that time, approximately 200 companies were founded with open source as the core technology. Collectively, these companies have raised over $10B in capital with a trend in the last 10 years towards bigger and bigger deals. In fact, three-quarters of the companies and 80% of the capital raised have come about after 2005. And I think we are just at the start of this renaissance.

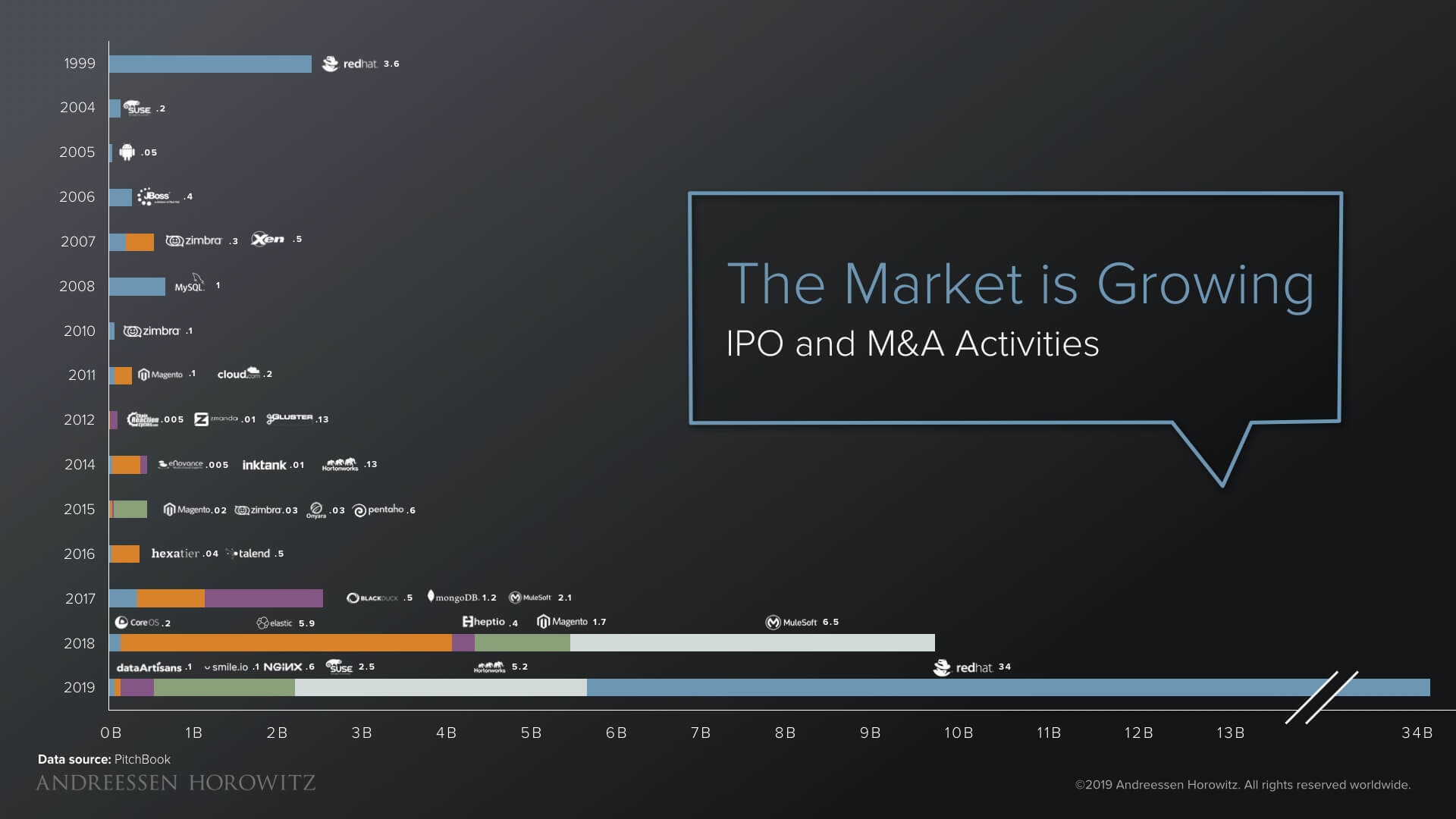

These investments are leading to bigger IPOs and larger M&A deals.

It’s interesting to note that, in 2008, mySQL was purchased by Sun Microsystems (which Oracle later acquired) for $1B dollars. At that time, I was convinced that $1B represented the maximum that any open source company would ever get. It was the bar for many years, and $1B was seen as a tremendous exit by the software industry which viewed open source as a commodity.

But look at what happened in the last few years. We have Cloudera, MongoDB, Mulesoft, Elastic, and GitHub that were the part of multi-billion dollar IPOs or M&A deals. Then, of course, there is RedHat. In 1999, it went public at $3.6B, and this year, it was sold to IBM for $34B. In the future, I’m excited to see if new bars will be set.

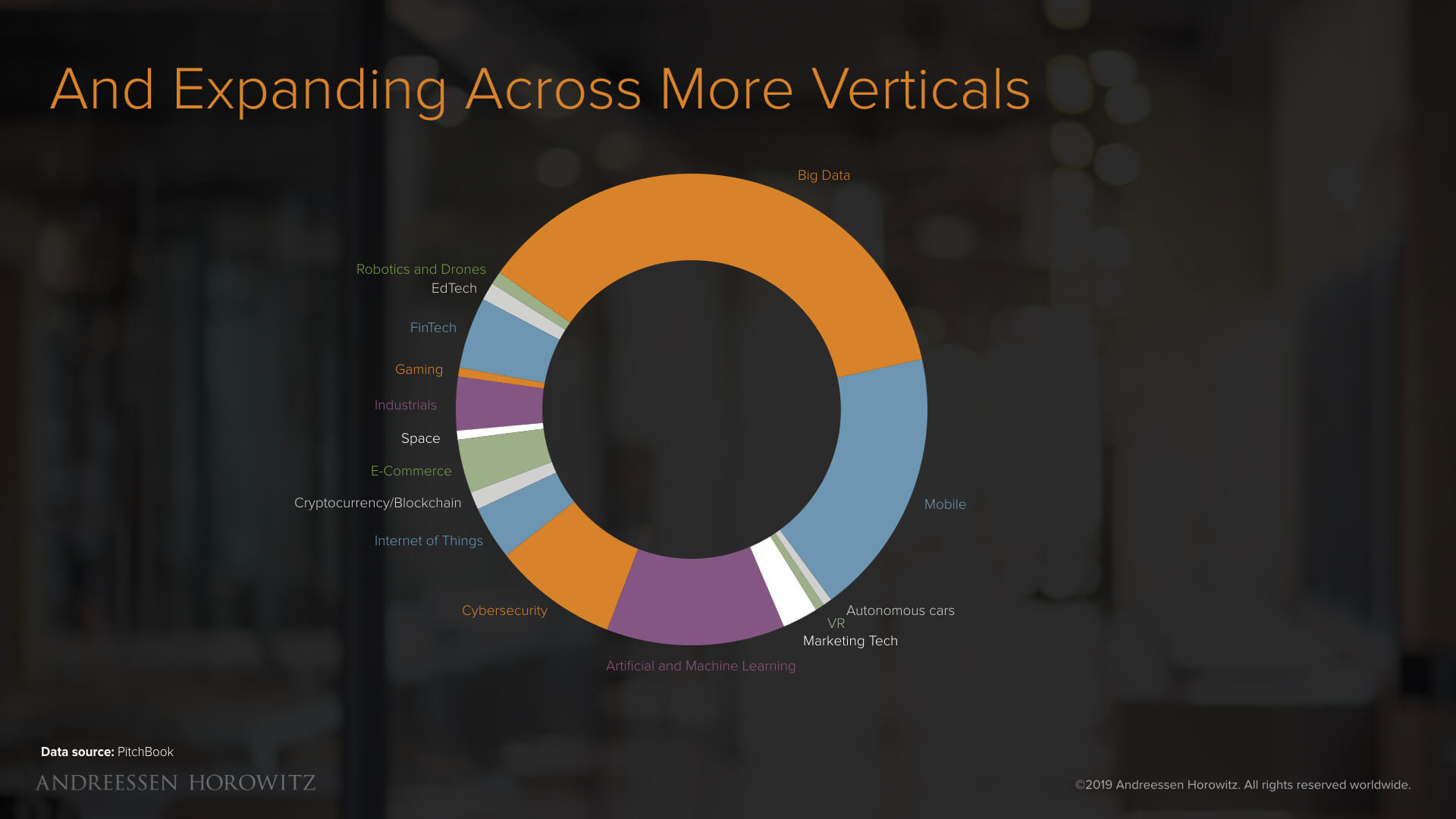

Open source is also expanding to more areas of software. Traditionally, OSS was mostly developed around enterprise infrastructure, such as databases and operating systems (e.g. Linux & MySQL). With the current renaissance, active OSS development is occurring in almost every industry – fintech, ecommerce, education, cybersecurity and more.

So what is behind this renaissance? To understand that, let me take a walk down memory lane and the history of open source.

The History of Open Source from Free to SaaS

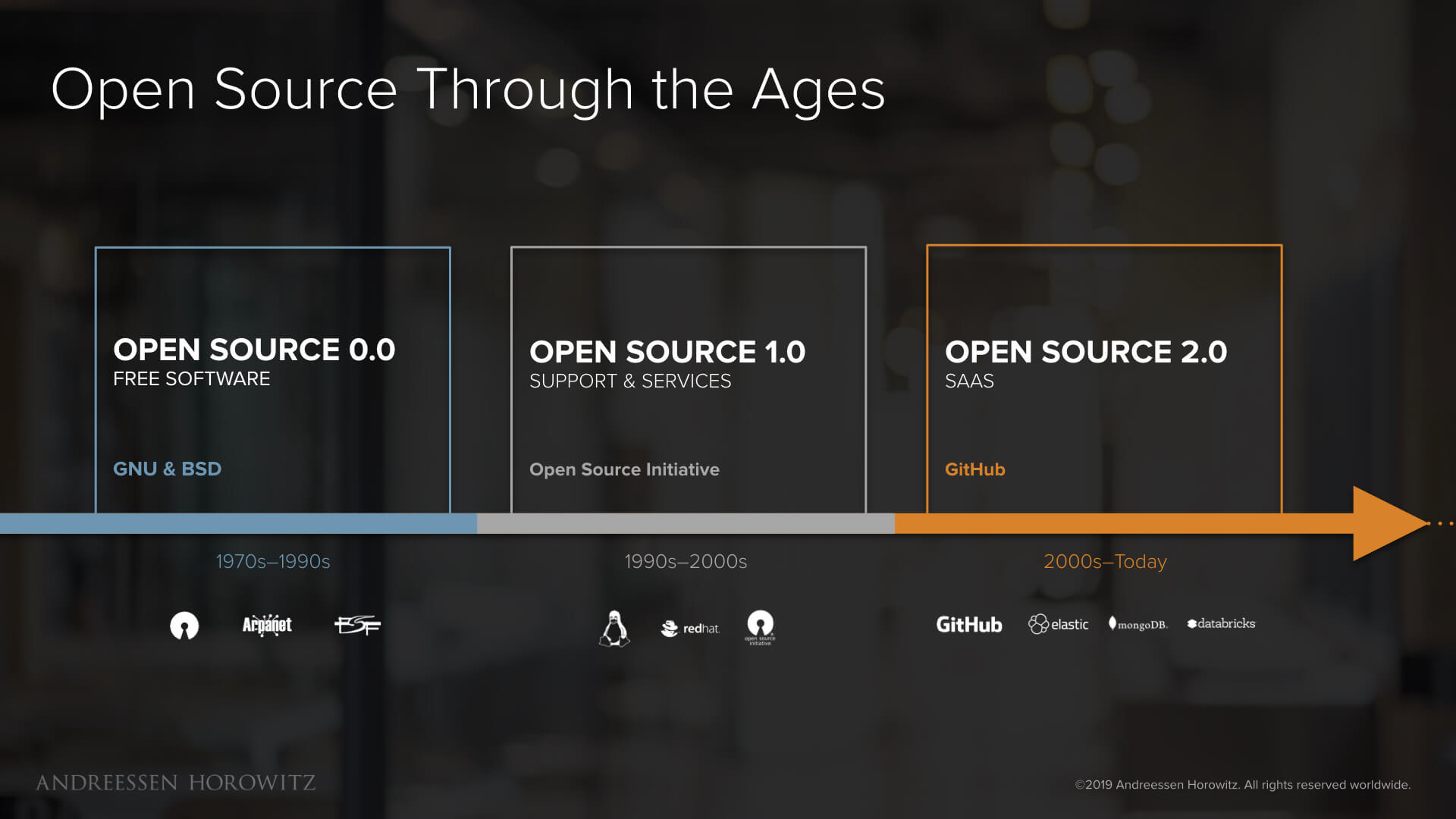

Open Source 0.0 – The “Free Software” era

Open source started in the mid-70s, and programmer that I am, I call this era 0.0 – the “free software” era. Academics and hobbyists developed software, and the whole ethos was: give software away for free. As ARPANET gave way to the internet, networks made it much easier to collaborate and exchange code.

I remember going to work at MIT or the Open Software Foundation at the time for work, and I had no idea where my paycheck came from. There was no concept of a business model, and the money behind “free software” development, if there was any, came in the form of university or corporate research grants.

Open Source 1.0 – The Support and Services era

With the arrival of Linux in 1991, open source became important for enterprises and proved a better, faster way to develop core software technologies. With more and more foundational open source technologies, open source communities and enterprises began to experiment with commercialization.

In 1998, the Open Software Initiative coined the term “open source,” and around that time, the first real business model emerged with RedHat, MySQL, and many others doing paid support and services on top of free software. This was the first time we saw a viable economic model to support the development of these organizations.

The other thing notable at this time was the value of open source companies paled in comparison to their proprietary counterparts. When I look at RedHat versus Microsoft, mySQL versus Oracle, XenSource versus VMWare, the value of the closed source company was so much greater than the open source counterpart. The industry deemed OSS a commodity that could never realize anywhere near the potential economic value of a proprietary company.

Open Source 2.0 – The SaaS & Open Core Era

By the mid-2000s, those valuations started to shift. Cloud computing opened the aperture and allowed companies to run open source software-as-a-service (SaaS). Once I can host an open source service in the cloud, the user does not know or care if there is open source or proprietary software under the hood, leading to similar valuations of open source and proprietary companies and indicating that open source really has real economic and strategic value.

A wave of acquisitions, including of my own startup XenSource by Citrix (not to mention MySQL by Sun and then by Oracle), has also made open source a key component of large tech companies. In 2001, Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer called Linux “a cancer.” Now, even Microsoft uses open source in its technology stack and invests heavily in contributing to open source projects. As a result, the next open source startup is as likely to spin out of a major tech company as out of an academic research lab or a developer’s garage.

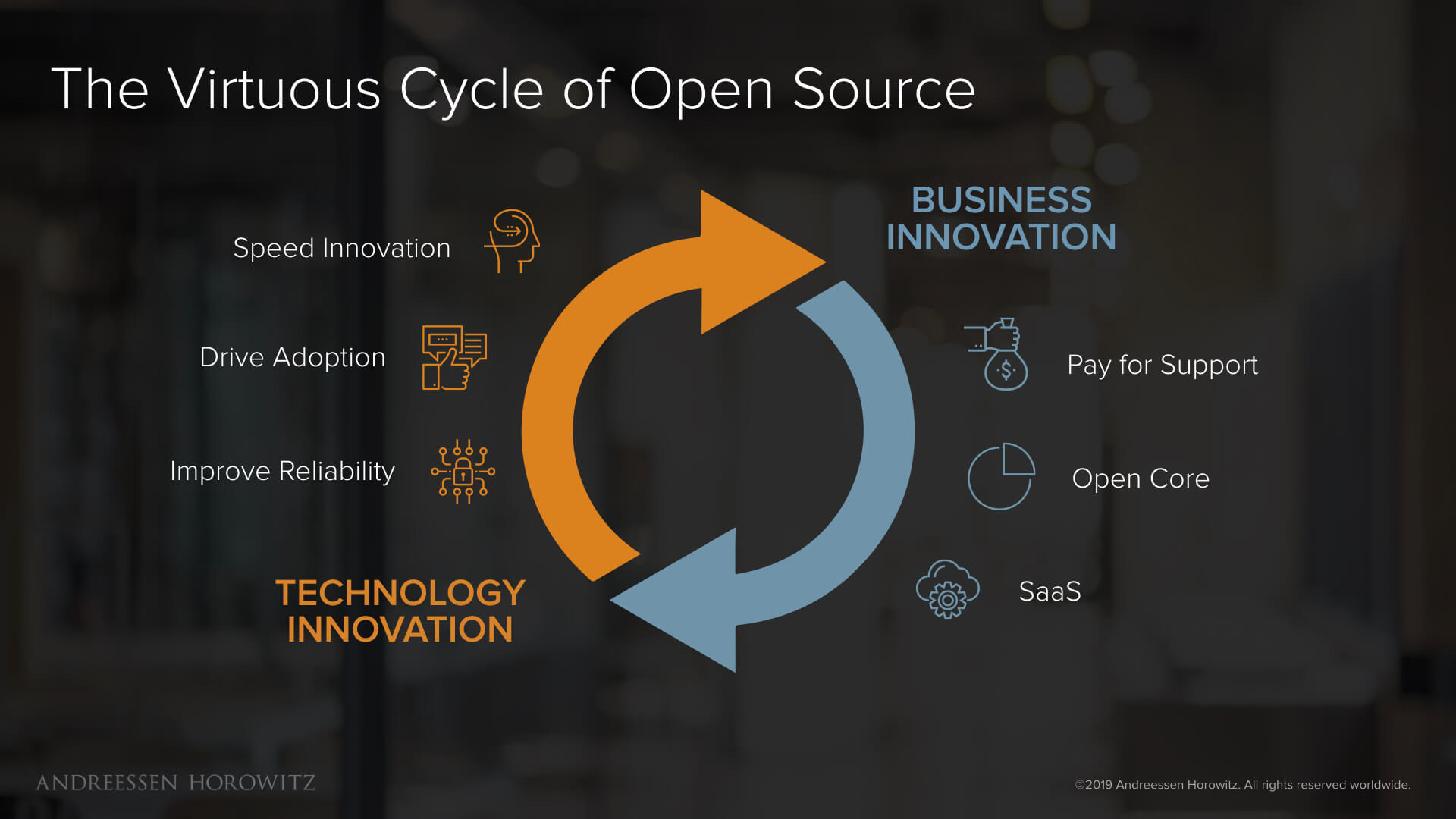

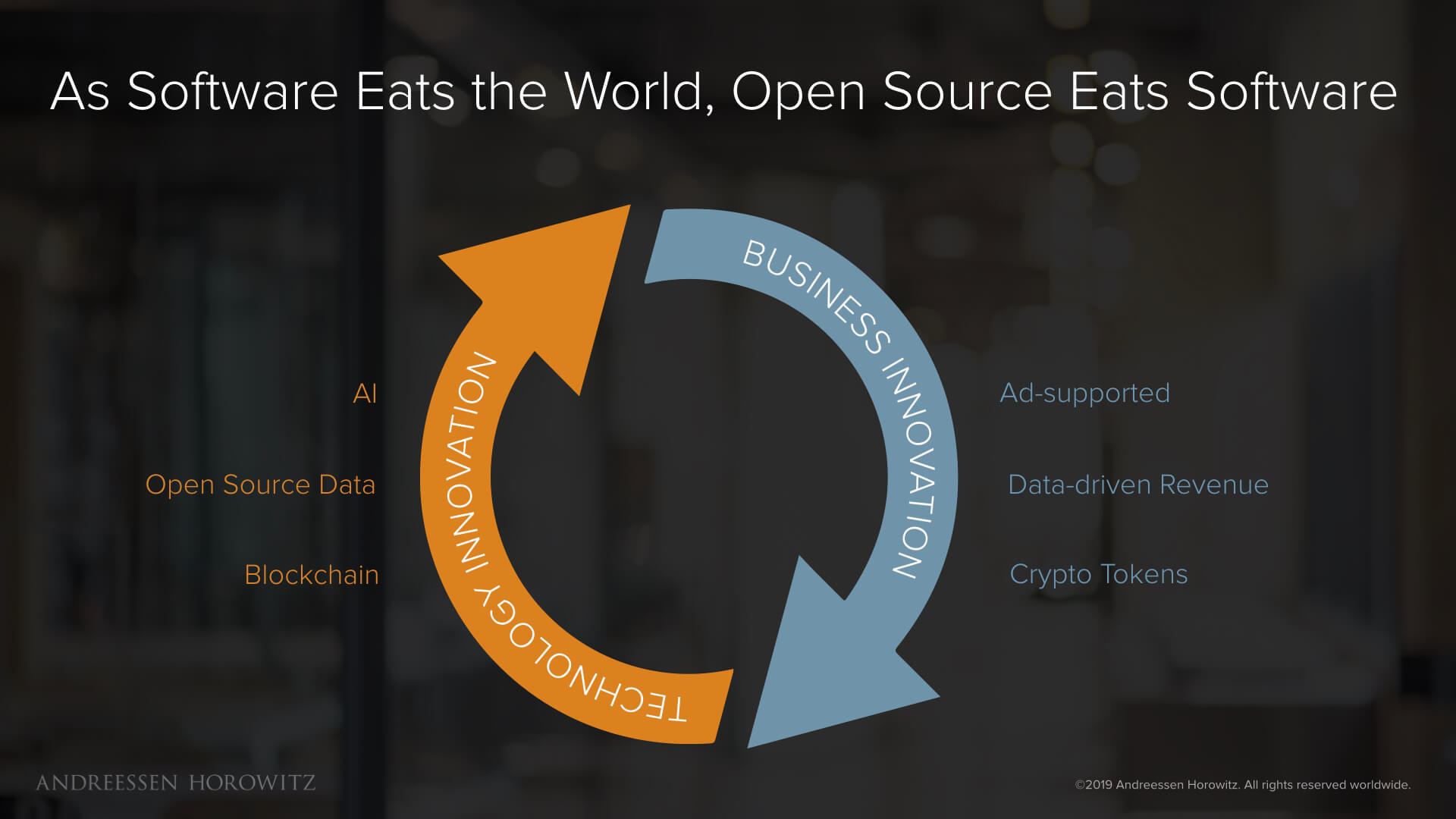

The Virtuous Cycle of Open Source

The history of open source highlights that its rise is due to a virtuous cycle of technology and business innovation. On the technical side, open source is the best way to create software because it speeds product feedback and innovation, improves software reliability, scales support, drives adoption, and pools technical talent. Open source was a technologically driven model, and these traits have been there since the “free software” era.

The full potential of open source is only realized, however, when technological innovation is paired with commercial innovation. Without business models, such as pay for support, Open Core, and the SaaS model, there would be no open source renaissance.

Economic interest creates a virtuous cycle, or flywheel. The more business innovation we have, the larger the developer community, which spurs more technological innovation, which increases the economic incentives for open source. I’ll talk at the end of the presentation about what I think is the future of open source in 3.0 and point out some of the interesting innovations that are currently happening on both the technological and business side.

But first, let’s talk about how to build open source businesses.

Business Success Centers on Three Pillars

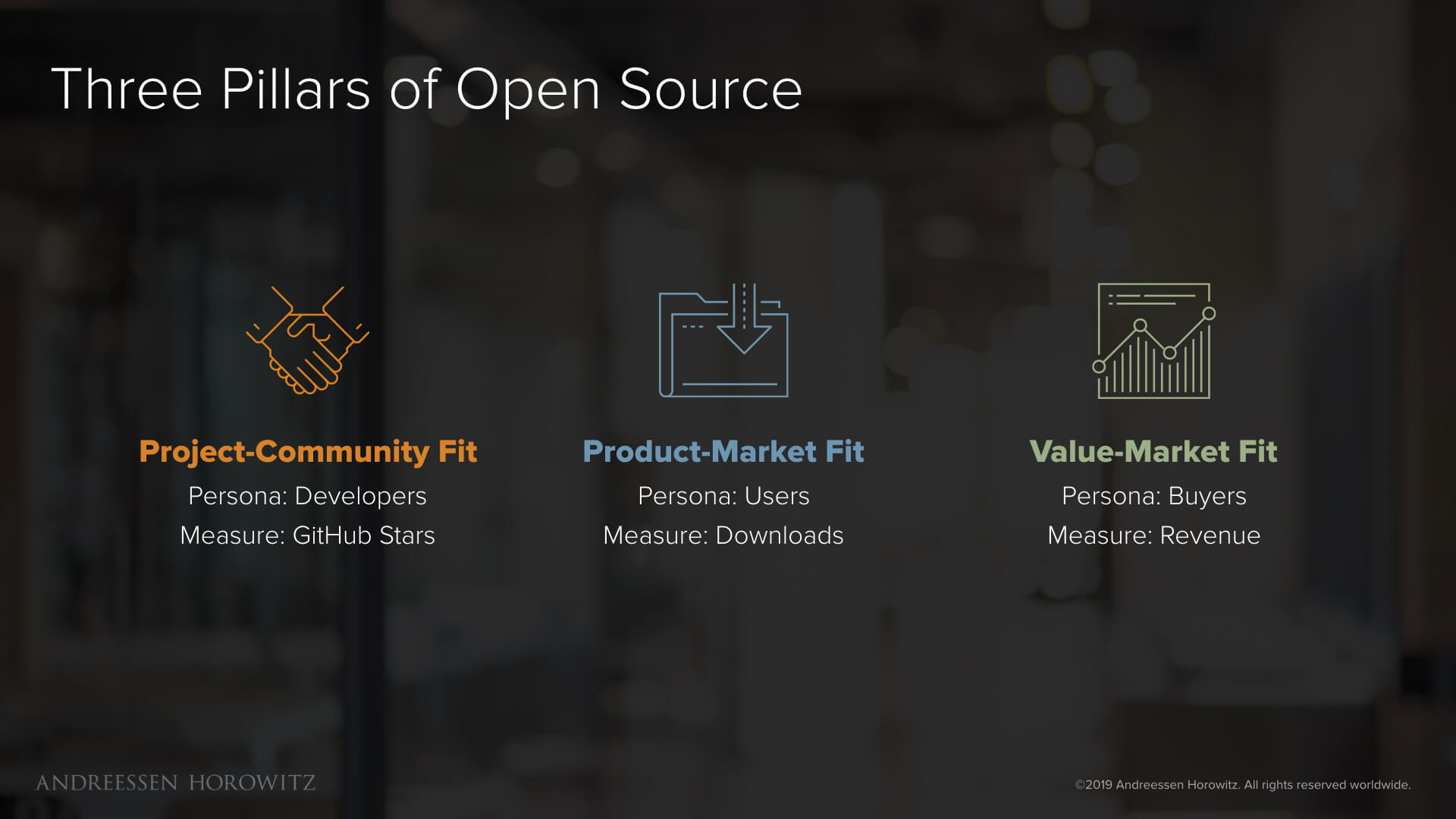

The success of open source businesses rests on three pillars. These unfold initially as stages with one leading to the next. In a mature company, they then become pillars that need to be maintained and balanced for a sustainable business:

1.Project-community fit, where your open source project creates a community of developers who actively contribute to the open source code base. This can be measured by GitHub stars, commits, pull requests or contributor growth.

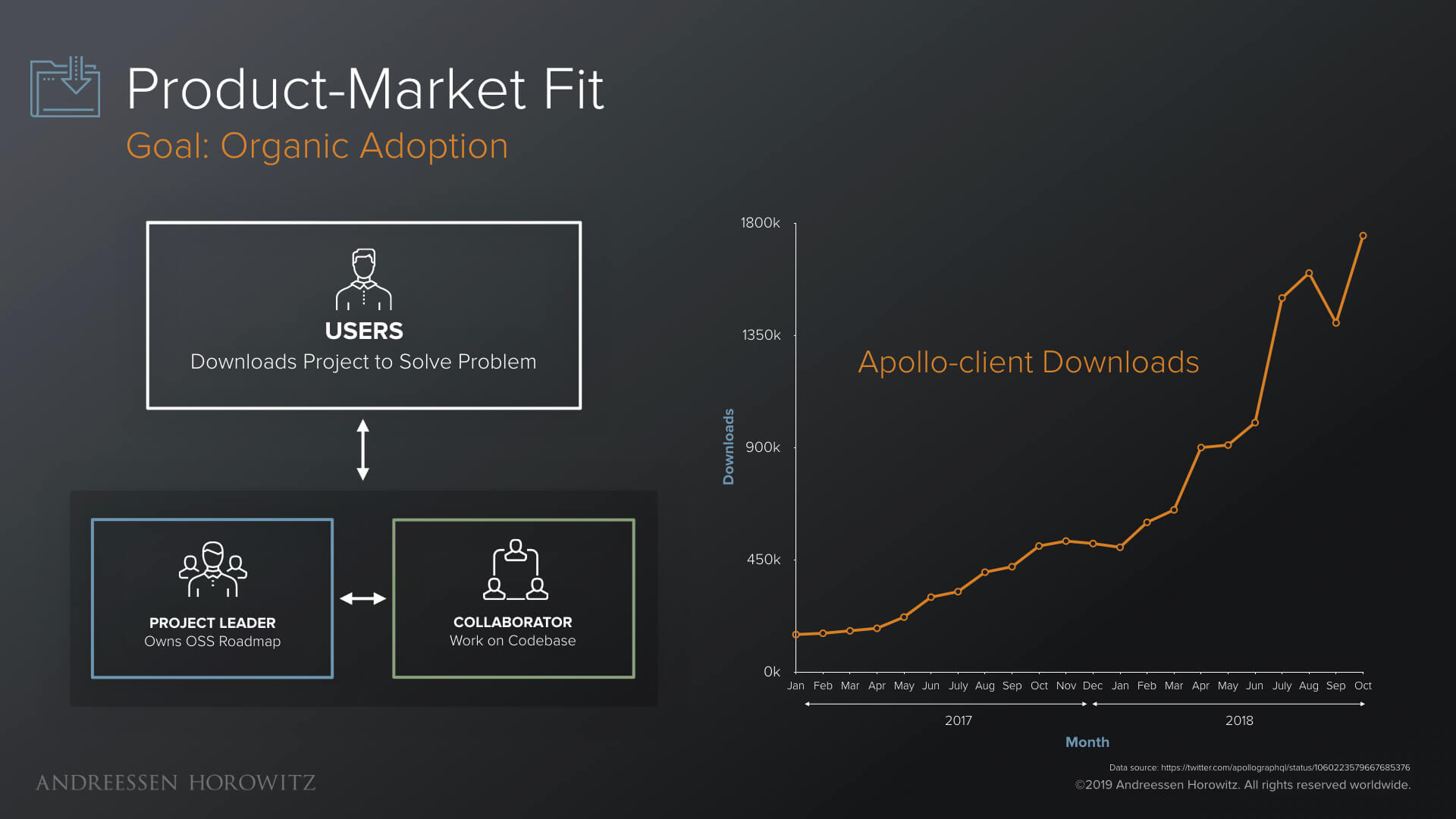

2.Product-market fit, where your open source software is adopted by users. This is measured by downloads and usage.

3.Value-market fit, where you find a value proposition that customers want to pay for. The success here is measured by revenue.

All three pillars have to be present over the life of a company, and when each has a measurable objective.

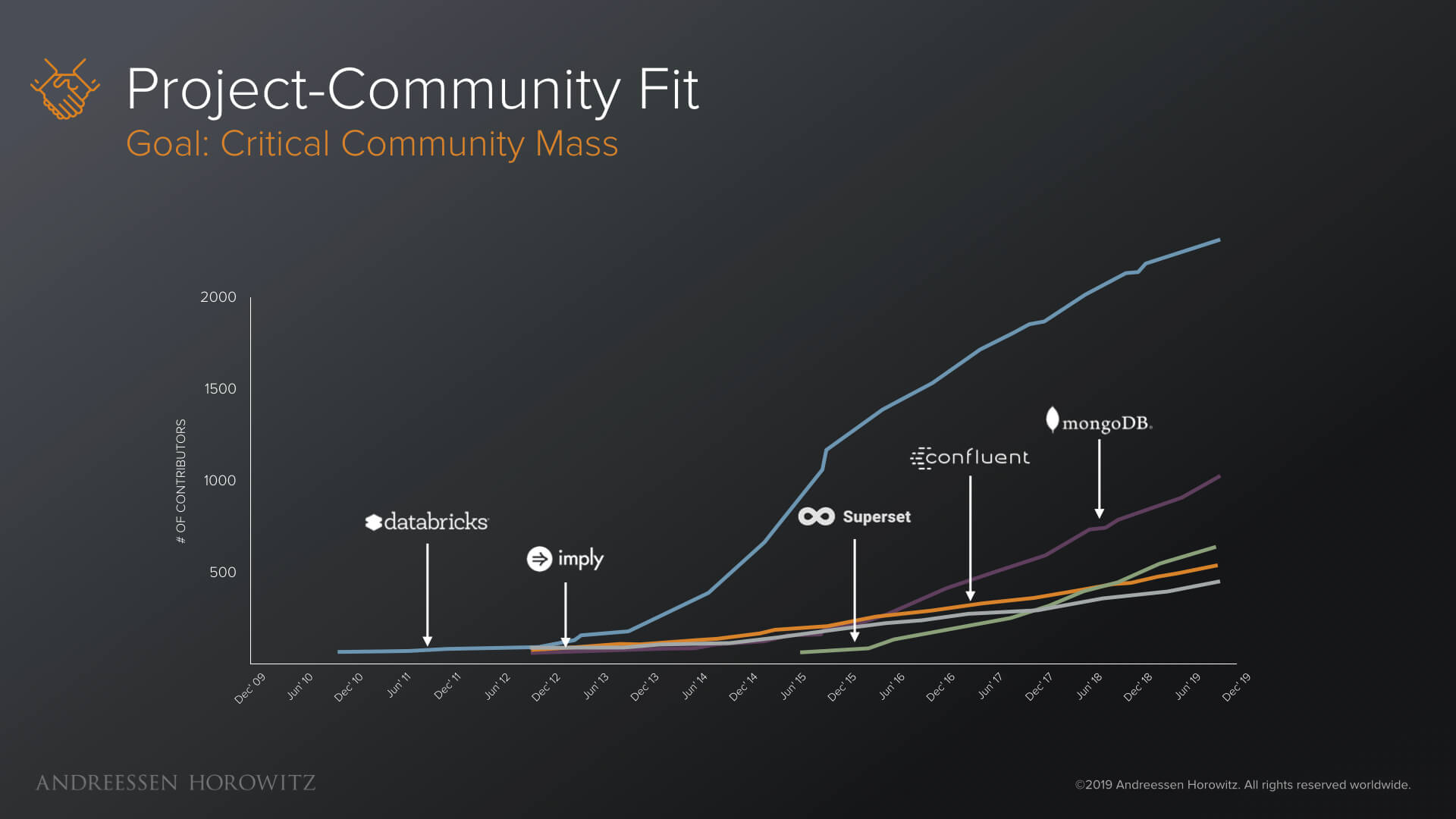

Project-Community Fit

Project-community fit is the first pillar and is about critical community mass and the traction of a project with developers. Though the size of OSS communities varies, strong followings and increasing popularity are key indicators that an OSS project spurs strong interest in a group of developers. The indicators include GitHub stars, the number of collaborators, and the number of pull requests.

Open source projects can start in many places, including inside large companies or academia. But it’s less important where a project starts, than that it has a project leader to drive the effort and that project leader typically becomes the CEO of the commercial entity.

Achieving project-community fit requires high touch engagement and continual recognition of the developer community. The best project leaders will reach a delicate balance between inclusion and assertion — making clear decisions to provide project direction while making sure everyone’s voice is heard and contributions are recognized. When this balance is struck, the project will sustain healthy growth and attract more people to contribute to and distribute the project. and distribute the project.

As investors, we are strongly biased towards funding OSS project leaders since they know the codebase in and out and are custodians of an ethos and vision that sustains a community of developers.

Product-Market Fit

Once you have a project leader and active group of collaborators, the next phase is to understand and measure product-market fit. In this process, project leaders need to crystalize: what is the problem the open source software helps to solve? Who is it solving that problem for? And what are the alternatives in the market? Without a clear understanding of your users and their use cases, projects can be pulled in many directions and lose momentum.

When the above questions are answered, you’ll observe organic adoption, as measured by the number of downloads. Product-market fit is the precursor to later sales engagement. Ideally, OSS users become top-of-funnel leads for value-added products or services – something we’ll look at more in our go-to-market section.

While working on product-market fit, it is important to think about what will delineate your commercial product and how you will deliver value that someone is willing to pay for. A common pitfall that I want to note is that sometimes an OSS product can be too good. The product-market fit may be phenomenally good, such that there is no need for value-market fit, meaning there is no natural extension to drive revenue. As a result, while you are driving organic adoption, you and your community should consider carefully what you may expect to commercialize in the future.

Value-Market Fit

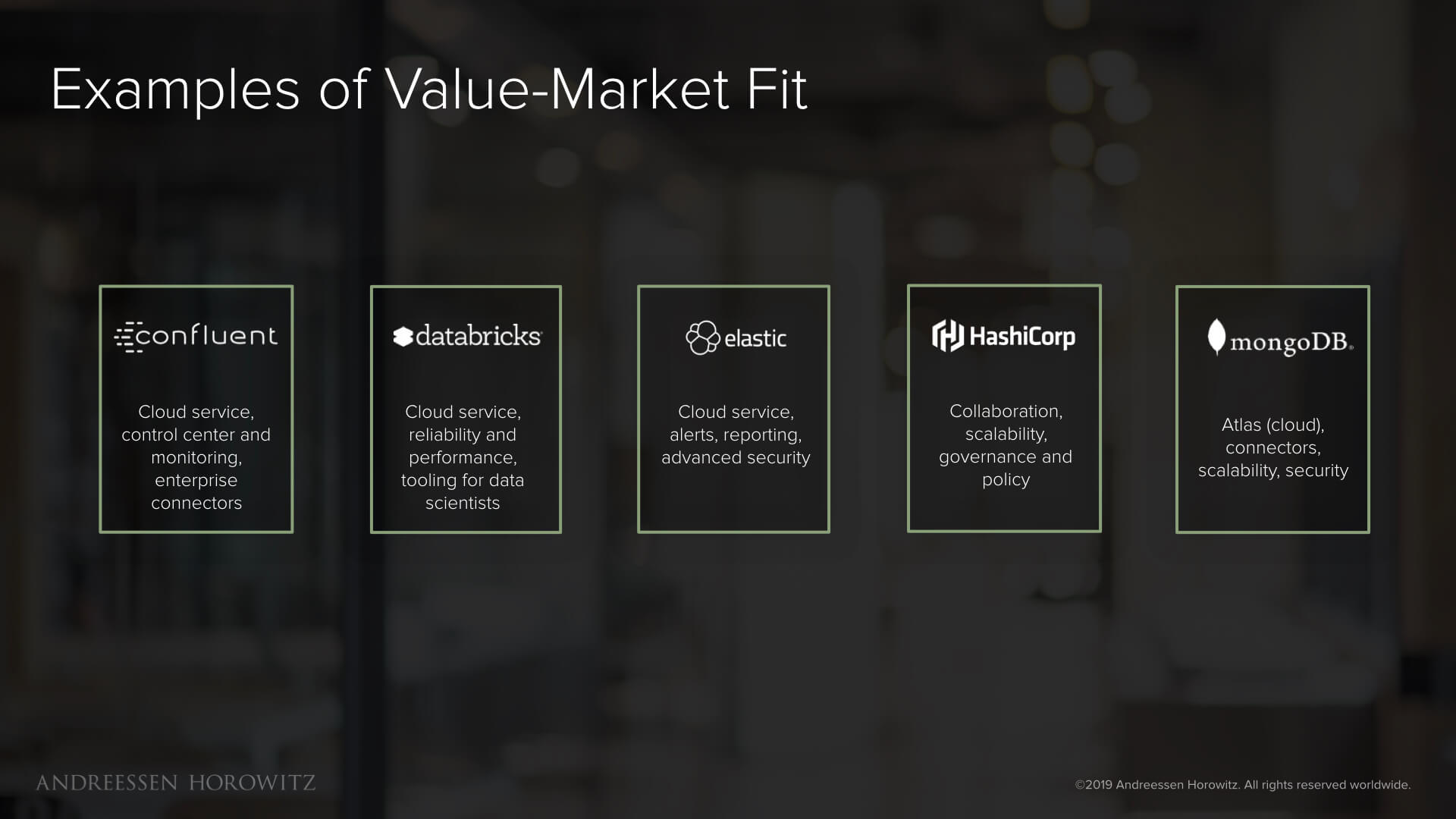

The last stage, and often the most difficult, is finding value-market fit and generating revenue. While product-market fit often accrues to individual users, value-market fit typically centers on departmental and enterprise buyers. The secret to value-market fit is to focus on what customers care about and are willing to pay for, not what you can monetize.

Often value-market fit is less about what the product does and more about how it gets adopted and the type of value it drives. The value OSS provides is not just its functionality, but its operational benefits and at scale features. So when thinking through a commercial offering, some questions to consider are: does your product solve a core business problem or provide clear operational benefits? Is it hard to replicate or find alternatives? Are there at-scale capabilities required for teams or organizations that are not realized in the OSS?

Though not an exhaustive list, open source companies have found value-market fit around features, such as:

- RAS (reliability, availability, security)

- Tooling, add-ons

- Performance

- Auditing

- Services

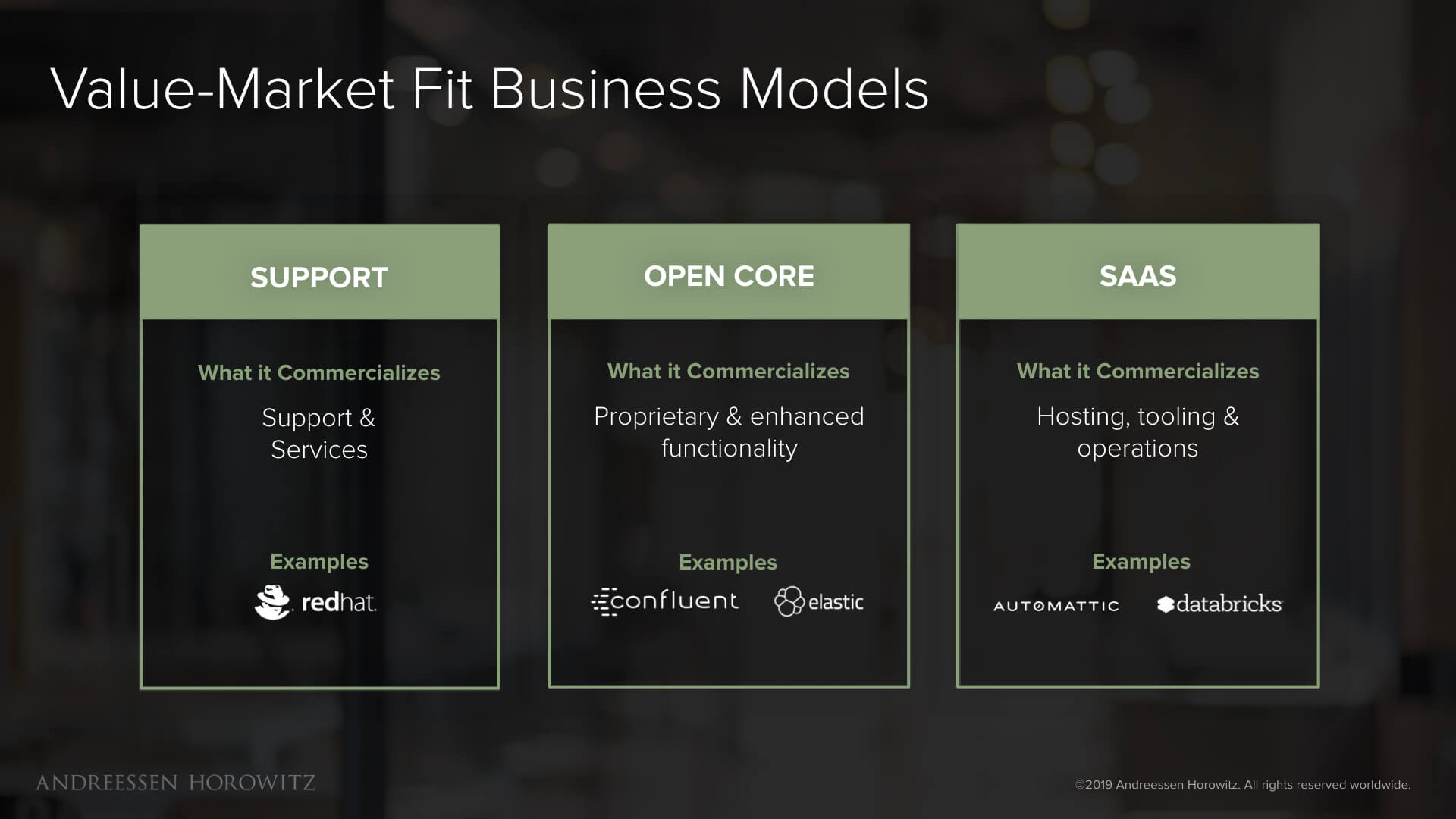

Choosing a Business Model

What business model you choose comes down to what value you can provide to customers and how best to provide it. It’s important to note that these business models are not exclusive, and it’s possible to build a hybrid business with elements of multiple models.

Support and Services was the model of the Open Source 1.0 era, and RedHat has really cornered the market on this and achieved scale. If you decide to go down this path, you will likely end up competing with RedHat (which is why five years ago, I wrote the blog post “Why There Will Never Be Another Red Hat: The Economics of Open Source.”)

The Open Core model, which layers value-added proprietary code on top of the open source software, is a good model for on-premise software. If you have super valuable components (such as security or integrations) that can be kept proprietary without harming the open source adoption, Open Core will be a fine model. A note of caution: with Open Core, community alienation can become a problem when deciding which features belong in which code. I saw that at my own company, and finding the right calibration with the community was very important. The ultimate pitfall here is that your community decides they don’t like your behavior on the proprietary side and they fork the project, or start a new project around the same codebase.

In a SaaS model, you provide a complete hosted offering of the software. If your value and competitive edge is in the operational excellence of the software, then SaaS is a good choice. However, since SaaS is usually based around cloud hosting, there is the potential risk that public clouds will choose to take your open source code and compete.

The Cloud & Competitive Moats

Once an open source business reaches a certain maturity, the threat of public clouds and topic of licensing is likely to come up. Licensing is a heavily debated topic, and while it’s important, I see companies spend too much time debating licensing in their early days.

I also think we have over-rotated on the threat from public cloud vendors. While these vendors may host open source projects, to date, there isn’t a single open source company I am aware of that has been fully displaced by a cloud provider.

The more important question for an open source company to answer is: if code isn’t a competitive moat, what is?

The answer goes back to what makes open source so powerful to begin with: community and how you think about development. Independent open source companies have three big competitive advantages:

1.Enterprise customers don’t want vendor lock-in.

2.They want to buy from people who have written the code.

3.Big companies don’t have your expertise.

When you combine those three things, I think that’s a real competitive value-add and why we have not yet seen big clouds fully displace stand-alone open source companies.

Now that we’ve covered the three pillars, let’s look at how you build an organization around them.

The more important question for an open source company to answer is: if code isn’t a competitive moat, what is? Community.

The Go-to-Market: Open Source is Top-of-Funnel

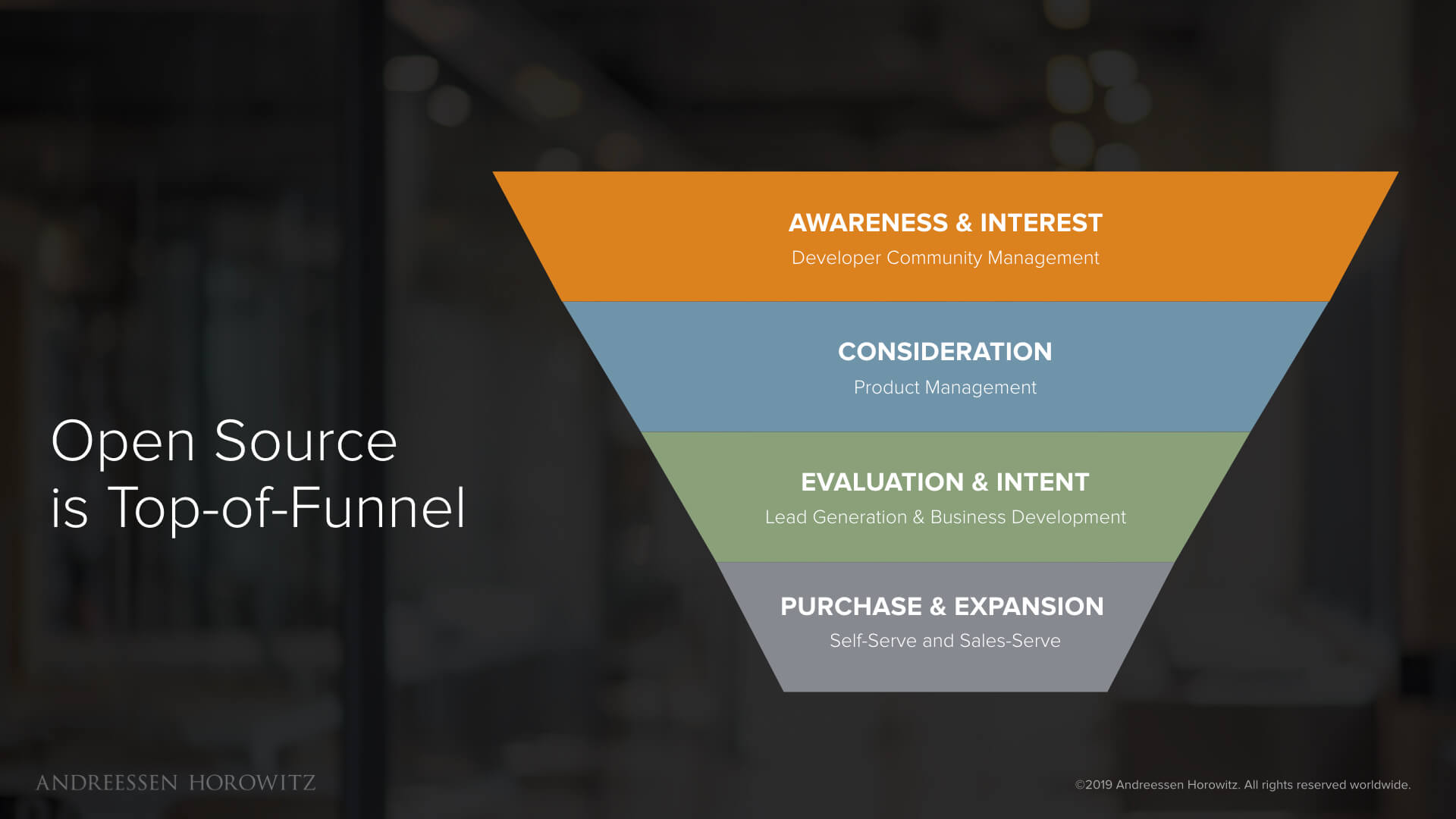

Your open source community is a developer-driven top-of-funnel activity. Building a business is about connecting that open source top-of-funnel to a strong value-driven commercial product. The idea of a funnel is not new, but it does play out differently for open source companies. In this section, I want to cover how the open source effort integrates and weaves into the commercial effort in different stages of the funnel, and how to get each stage to work harmoniously with the others.

The open source go-to-market funnel breaks down into four stages and key organizational functions.

- Developer community management drives awareness and interest in your open source product.

- Effective product management leads to a base of users for your free open source product.

- Lead generation and business development evaluate the intent of those users to identify potential value and selling opportunities in the enterprise.

- Self-serve (bottom up) and sales-serve (top down) motions deliver and expand the value of a paid product or service to the enterprise.

Let’s look at each of these stages and functions in more detail.

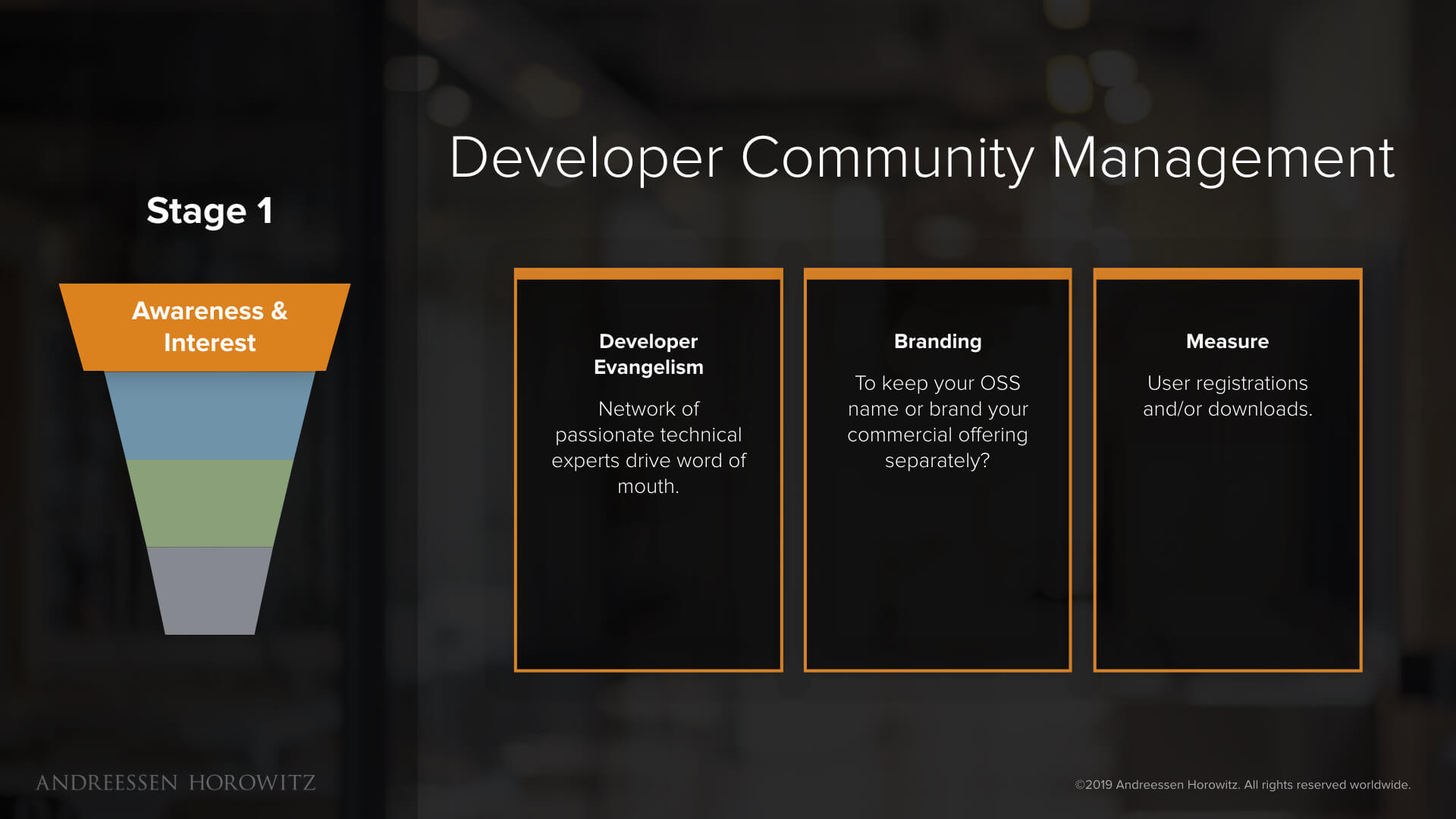

Stage 1: Awareness & Interest – Developer Community Management

Driving word of mouth with developers, as measured by user registrations and downloads, is absolutely critical to success in later stages of the funnel. In the early days of a company, founders often act as the first evangelists in the early days of a company. As the company expands, having a dedicated team of developer evangelists who have a mix of technical expertise and strong communication skills is important. While typically a rare combination, it’s usually easy to spot when someone has the mix of technical and communication skills. Once you do, hire those developers and get them at conferences and on social media engaging with developer communities and explaining the importance and value of your project.

While you need to align your sales and developer evangelist message, you do not want your community managers “selling.” They should generate interest and inform people about the product, and any emphasis on selling is likely to erode their credibility within the community.

As you launch your business, you will also need to decide if it will carry the same name and brand as the open source project. Companies have succeeded both ways, and there are pros and cons to each. Separate names, such as Databricks and Spark, prevent brand dilution and provide licensing flexibility, while the same name often provides more momentum from the OSS project, but can risk alienating the open source community if they perceive that they are being exploited for profit.

Finally, user registrations and downloads is a common measurement for both open source and proprietary software, so the secret sauce is not what you are measuring, but how accurately. At XenSource, we had inaccurate numbers at one point because our download metric included a large number of downloads that had been initiated, but not completed. Honing how you measure user registration and interest will prevent downloads from being a vanity metric that doesn’t lead to the next stage of the funnel.

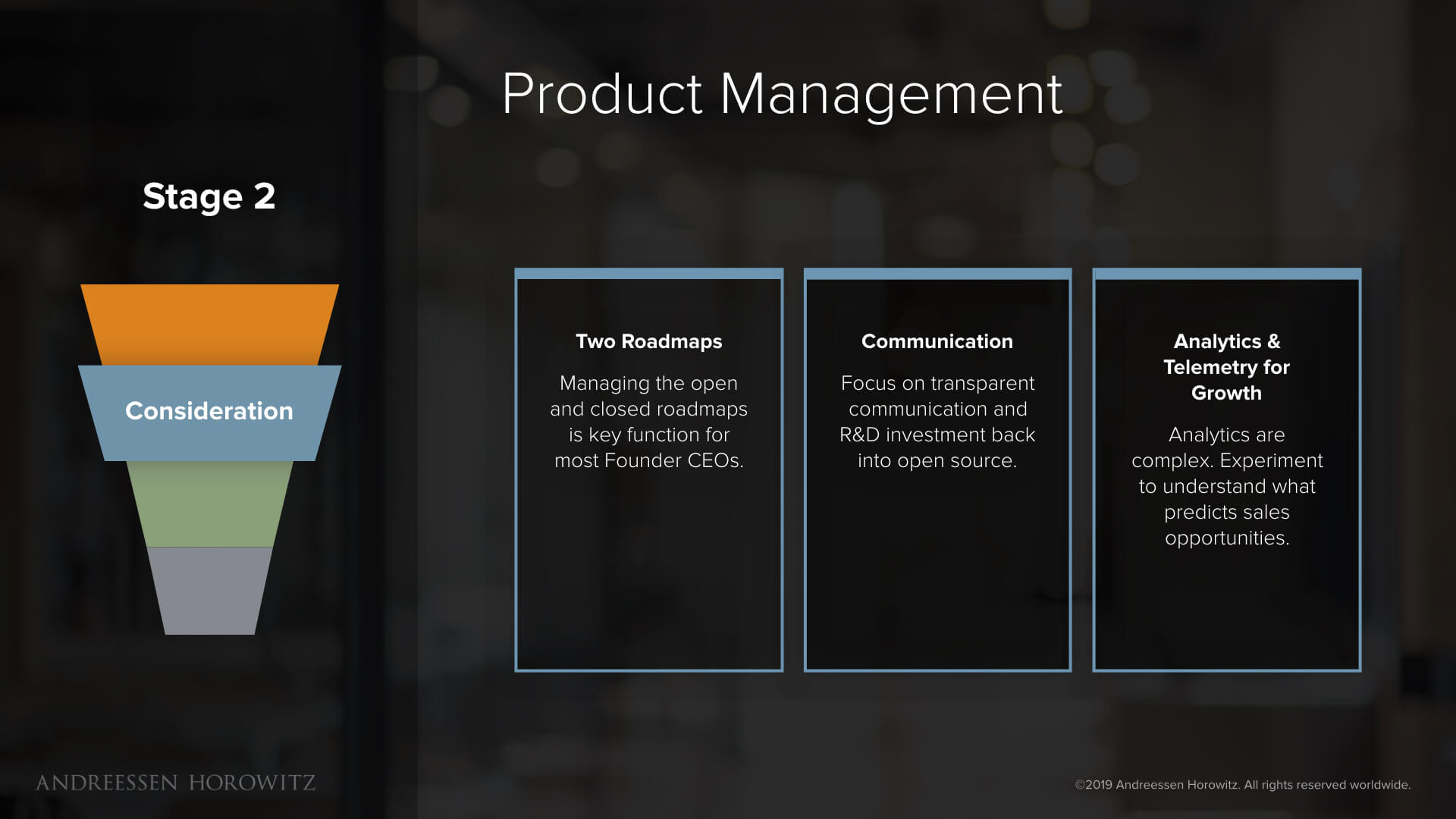

Stage 2: Consideration – Product Management

Next is consideration. Once you have engaged a developer community, your goal is to maximize developer and user love, adoption, and value. This second stage of the open source funnel is typically accomplished with product management.

Effective product management will execute a number of functions to support this stage: managing the closed and open source roadmaps, communicating the decisions to your developers and users, and building analytics into the product to collect more insights of usage patterns and predict sales opportunities.

Unlike proprietary software, open source businesses typically have two roadmaps to manage. OSS CEOs and founders often spend the majority of their time managing these roadmaps and how one feeds the other. I like to see this laid out on a single page to show how these interlock and relate and what features are available in each.

The most successful companies and founders have a framework or guidelines that helps them delineate and communicate what will be paid and what will be free. For instance, PlanetScale is committed to keeping open source anything that would produce vendor lock in, a value that maintains the good will of their open source community and enterprise customers. It is helpful to have a feature comparison table so customers and your community understand the different value the free software and paid software provide.

Transparency around research and development and incorporating community feedback into your product roadmap is particularly important to maintaining community trust. Many successful open source companies remain active, and often leading, contributors to the corresponding open source projects. For instance, Databricks has 10x the contributions to Spark of any other company.

When it comes to the product itself, you should build in analytics that help you understand your users and predict the percentage of OSS users who will convert to buyers. Once users have the product, product usage analytics will help identify product-market fit from value-market fit and the number of people likely to go from free to paid user to predict sales opportunities. For example, if five out of every hundred users consistently convert to paid users, then you can use 5% as an estimate to build your financial models.

This will be a complex process, and you should experiment with product packaging to recognize the optimal line between free and paid. For many open source founders, this product experimentation is a never-ending journey, and the success of their go-to-market hinges on tight product feedback cycles.

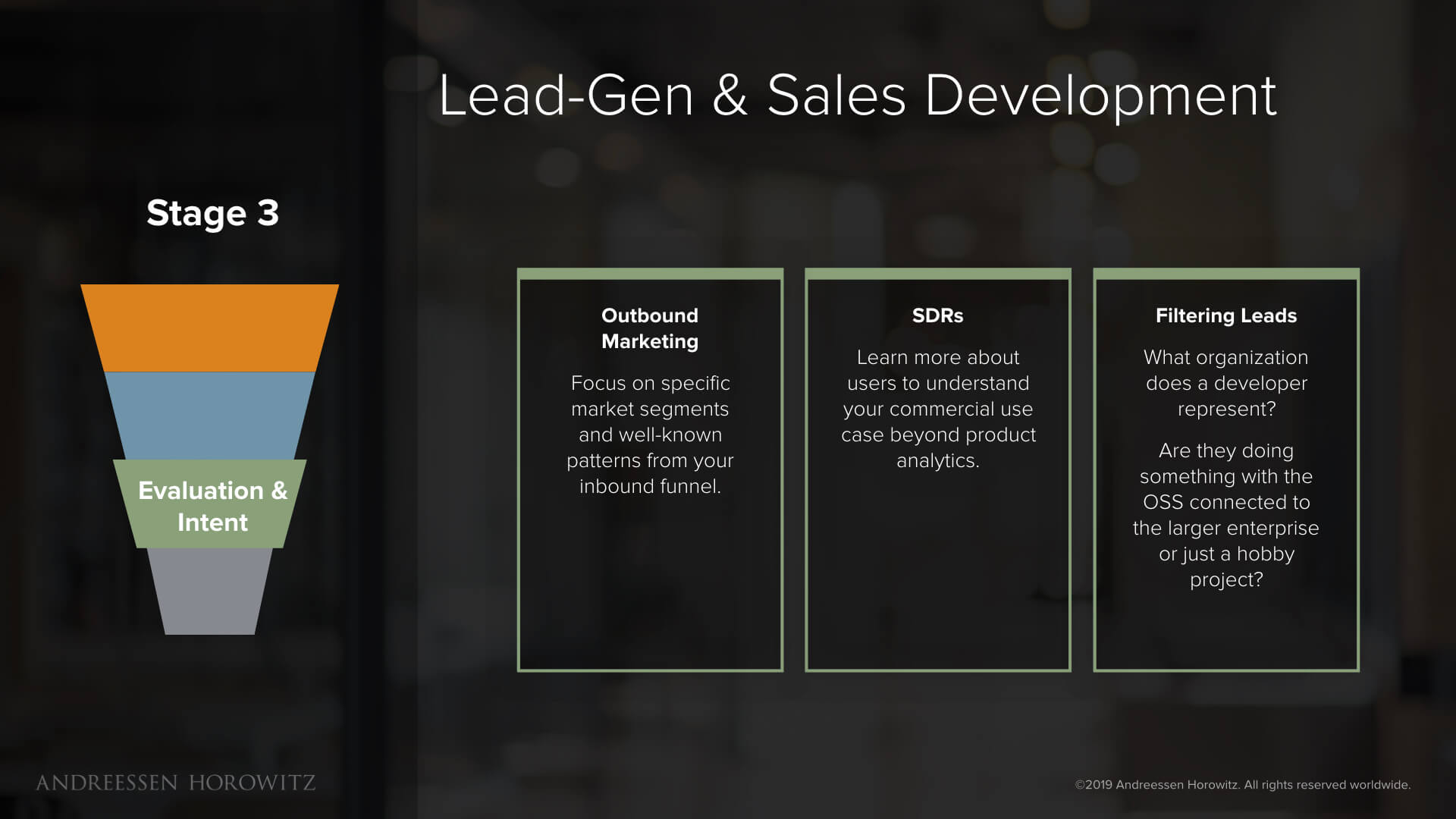

Stage 3: Evaluation & Intent – Lead Generation & Business Development

The next stage of funnel – evaluation and intent – is about validating and refining those theories with lead generation and sales development. The goal is to find the path from your users to an enterprise buyer with success measured by sales qualified leads (SQLs).

The first part of this is outbound marketing. Outbound marketing should prioritize campaigns focused on specific market segments, based on well-known patterns from your developer evangelism at the top of the funnel. Paying attention to your open source users, you will learn which roles and departments are using the product and what their interests are. You can then target your outbound marketing to the engineering managers, devops, or IT who will find your product valuable.

Next is a sales development effort. Sales development reps (SDRs) should take a customer success, rather than an overly salesy, approach and be insatiably curious about the needs of your users and what they are doing with the product.

As your campaigns generate leads, there are two primary filters to qualify them: 1) what organization does the developer or user represent? 2) did they download or engage with your project for something that is connected to a larger enterprise goal?

Stage 4: Purchase & Expansion – Inside & Field Sales

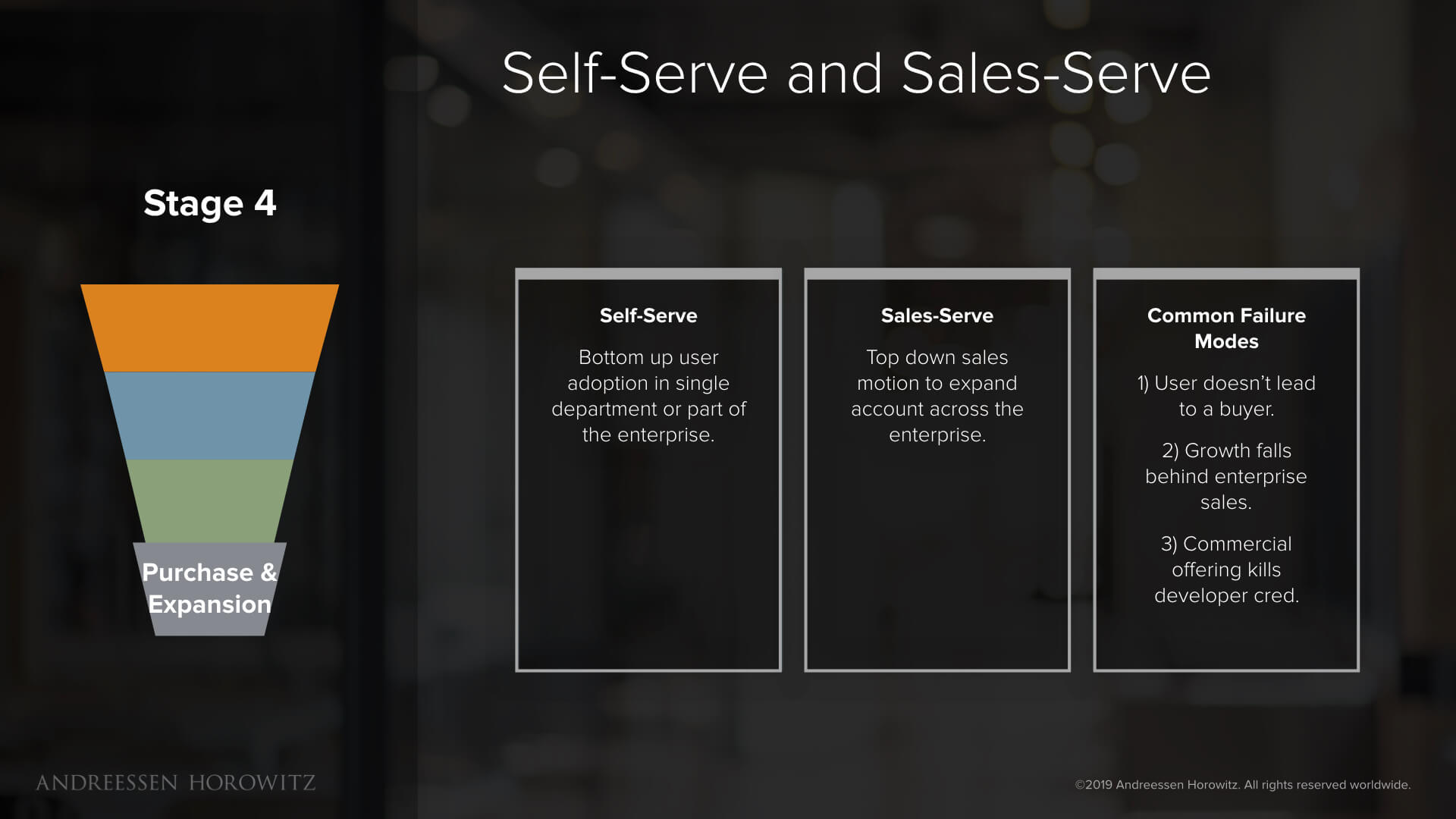

Once you have sales qualified leads, you may have two sales motions to enterprise. The first could be a self-serve bottom up motion, in which users within the enterprise organically adopt and pay for a product. Typically, this product will be for individuals. The second will be a sales-serve motion that uses a more traditional top down motion to land deals at departmental level or expand usage across the enterprise.

What Success and Failure Look Like

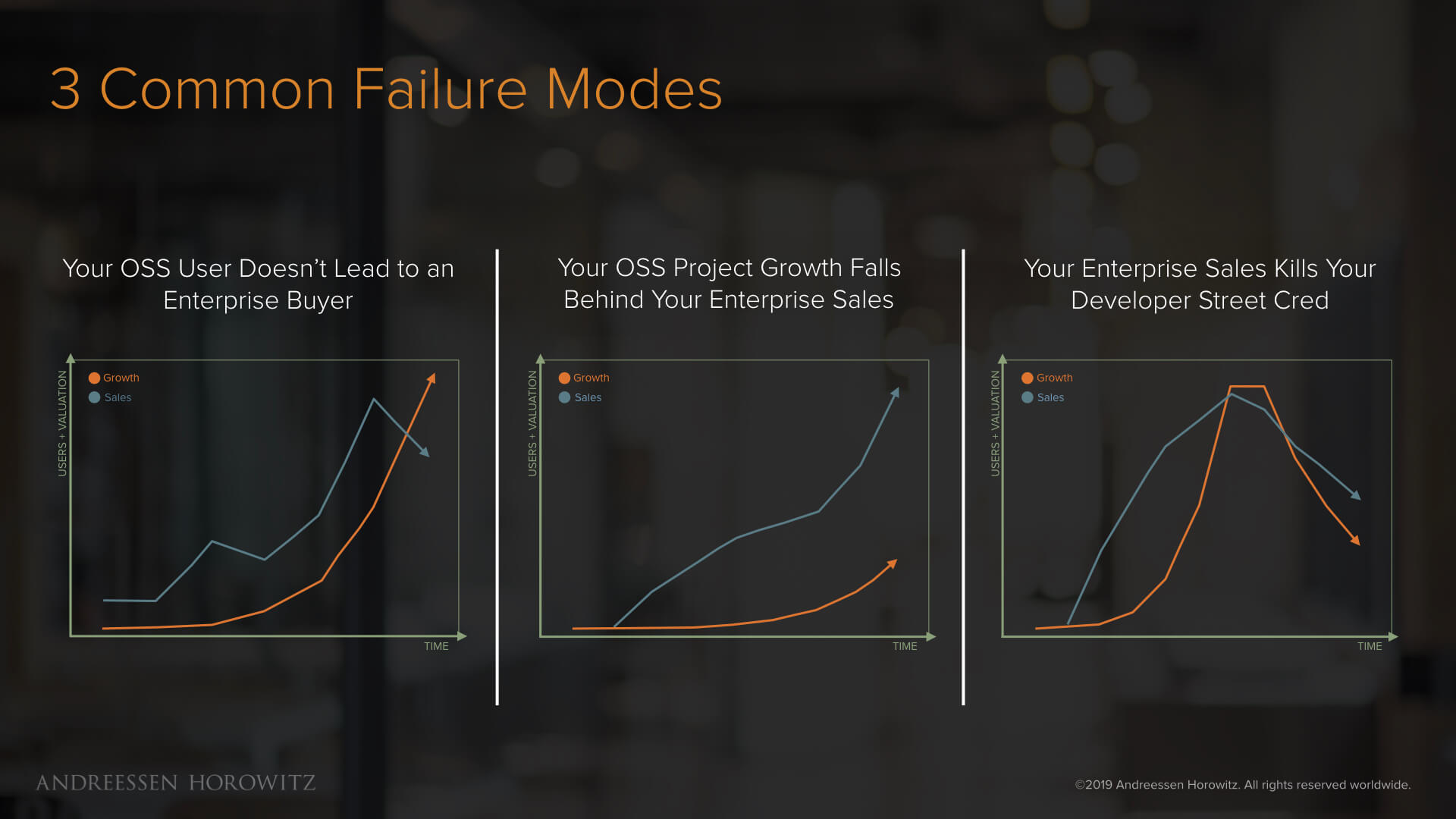

Coordinating organic growth and enterprise sales can lead to a few common failure modes for open source businesses, as my colleague Martin Casado pointed out in his Growth, Sales, and a New Era of B2B talk. In the first, your open source user doesn’t lead to a buyer. In this case, you have great product-market fit, but no value-market fit.

In the second failure mode, your OSS project growth falls behind your enterprise sales. Here, your product-market fit may not be that great. In the third, your commercial offering kills your credibility with developer communities. There is likely too much in proprietary and not enough in open source, and your open source project withers.

The top of funnel provides the key to all that follows, so invest first in your developer community, open source project, and users ahead of formal marketing and sales. And never lose sight of these three central questions: Who are your users? Who is your buyer? And how is your open source and commercial offering providing value to each?

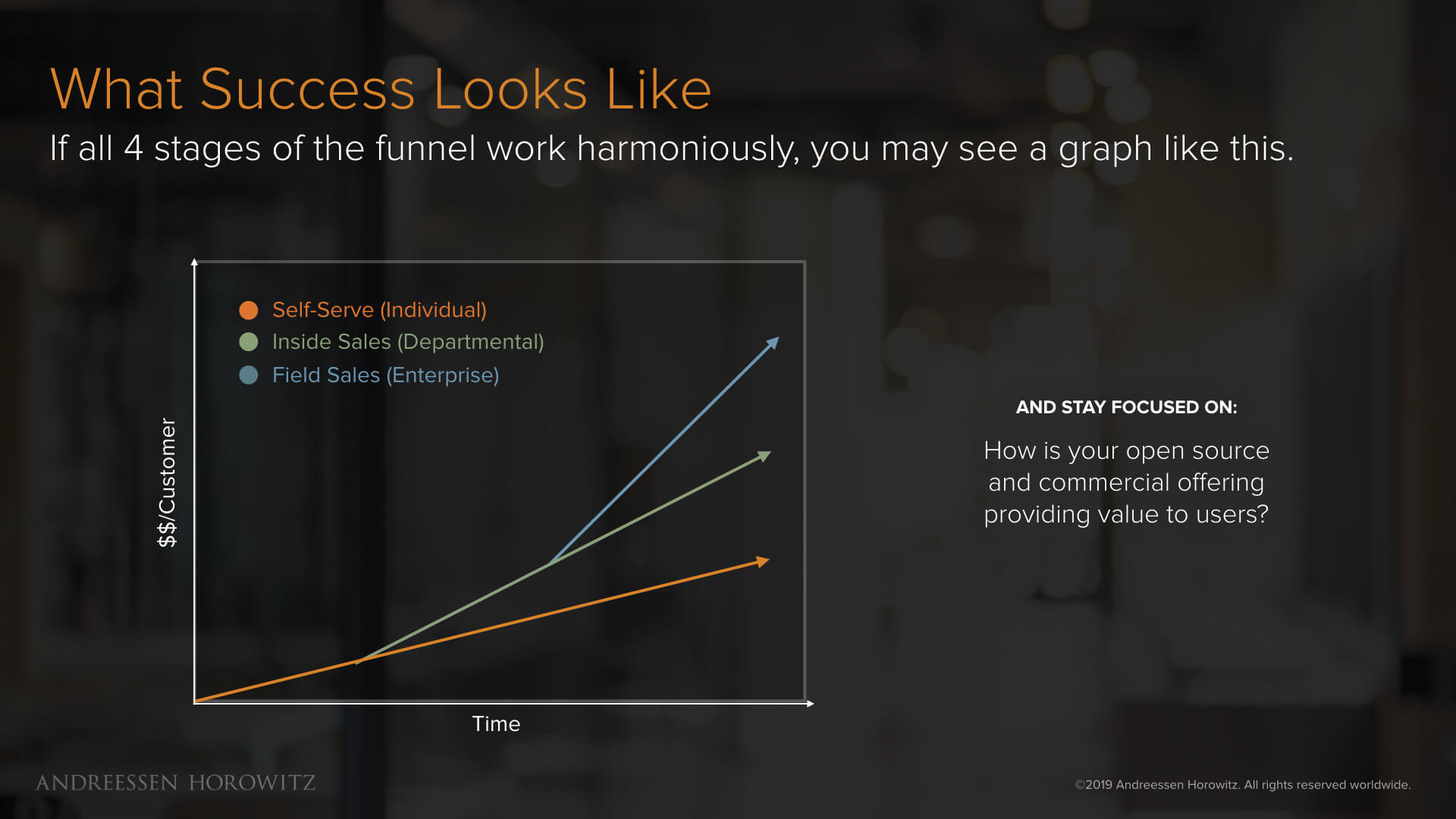

If successful, you may see a graph like the one above. On the y-axis, we have revenue per customer, and on the x-axis, time. This graph, which is really my direct observation as a former board member of GitHub, shows top down and bottom up selling as it aggregates together in revenue. The takeaway here is: it’s a good sign if your revenue looks like a layer cake. The orange line is bottom up revenue from an individual, and typically, that will be one revenue line. The next revenue line may be selling to departmental buyers, but this is top down, usually using inside sales. The next part of the layer cake is field sales, or direct sales, selling or expanding the account across the enterprise. To optimize each of these revenue lines, don’t let the sales motion just happen; have someone who owns that specific function and drives the effort purposefully.

Finally, depending on your product, you may only have self-serve or only have inside sales. That’s okay, and it really depends on the complexity of the product and where and how it is best used. I do find that most open source companies have some combination of top down and bottom up motions, often starting with bottom up and then building a revenue expansion function on top of it.

OSS 3.0 – Open Source is a part of every software company.

As software has eaten the world, open source is eating software.

Today, almost every major technology company, from Facebook to Google, is written on the backs of open source software. Increasingly, these companies are building their own open source projects as well – Airbnb, for example, has more than 30 open source projects, and Google more than 2000!

In the future, the virtuous cycle will continue. Technologically, AI, open source data, and block chain are some examples of emerging innovations. The next generation of business models may include ad-supported OSS, as when a large proprietary enterprise supports open source projects; data-driven revenue; and crypto tokens, which monetize blockchain.

I believe Open Source 3.0 will expand how we think of and define open source businesses. Open source will no longer be RedHat, Elastic, Databricks, and Cloudera; it will be – at least in part – Facebook, Airbnb, Google, and any other business that has open source as a key part of its stack. When we look at open source this way, then the renaissance underway may only be in its infancy. The market and possibilities for open source software are far greater than we have yet realized.

COMMUNITY CONTRIBUTORS: This guide was a true open source effort. It draws on wisdom from across the open source community. In particular, we would like to thank Ali Ghodsi (CEO, Databricks), Maxime Beauchemin (Project Leader, Superset), Jiten Vaidya (CEO, PlanetScale), Sugu Sougoumarane (CTO, PlanetScale), Marco Palladino (CTO, Kong), Paul St John (SVP, WW Sales, Github), Jono Bacon (Community Manager), Kevin Wang (CEO, FOSSA), Stuart West (SVP Ops, Automattic), Zeeshan Yoonas (CRO, Netlify), and Heather Meeker (OSS Licensing Lawyer).