Read more: a16z invests in Kalshi

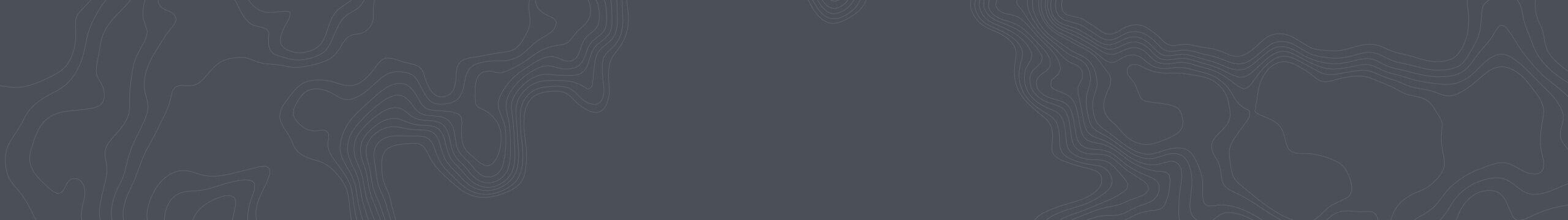

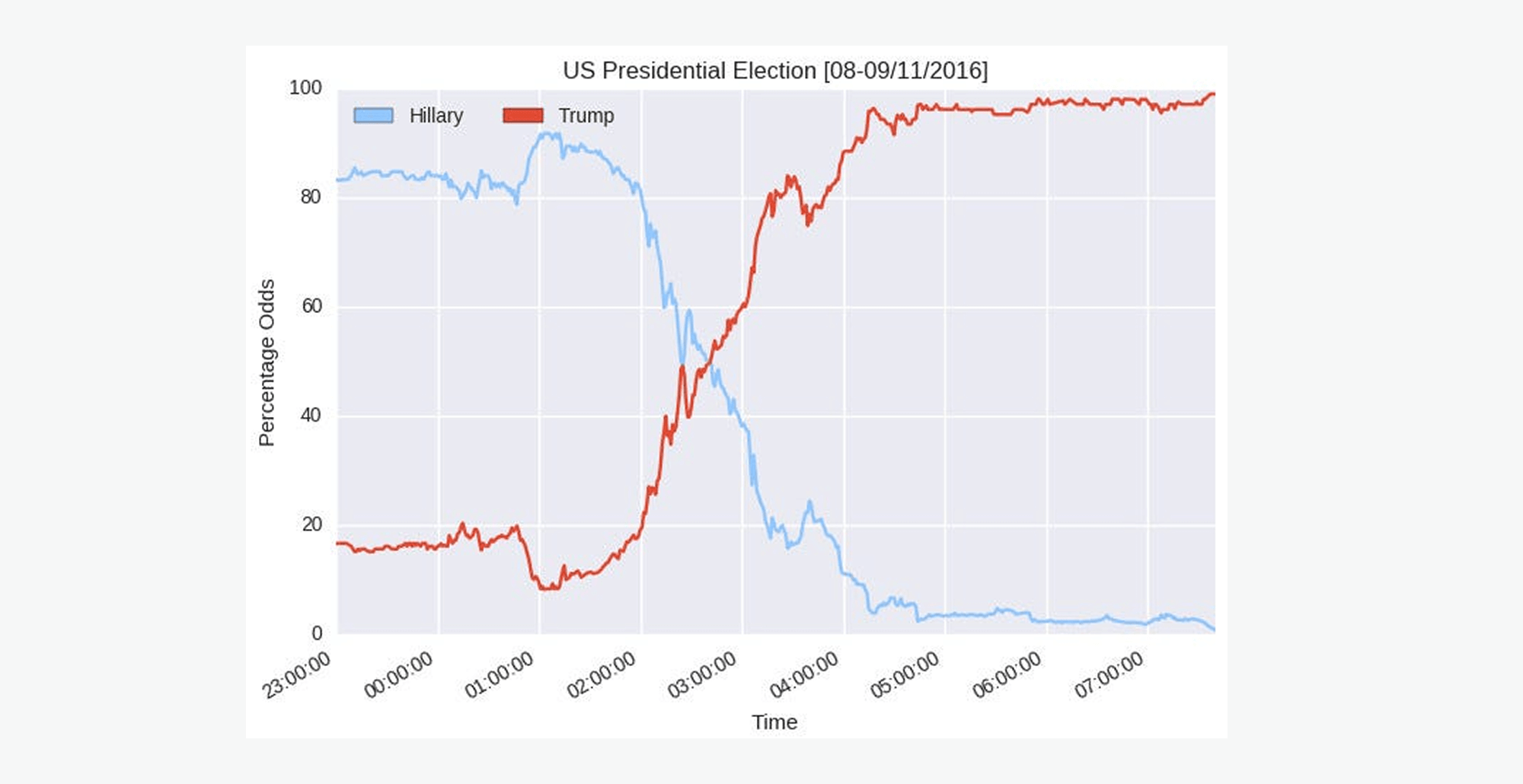

In the mid-2010s, a new visual content format started popping up around elections, sports games and playoff races: the “probabilities changing over time” graph. These graphs were a compelling content format because they told a fascinating story: what was supposed to happen, and then what did.

You can tell amazing stories with these images. Just by looking at changing probabilities, you could tell a story about collapse, about redemption, or about an underdog beating the odds. (Kurt Vonnegut famously gave names to many of these stories: like “man in a hole”, “boy meets girl”, and “from bad to worse,” each with their own shape.) These images are a kind of meme: they compress a lot of information into a tiny space, and faithfully transmit the story intact when shared.

As engaging as these graphs were, they came with one major limitation: they didn’t really exist outside of politics, sports, or financial markets. There’s an obvious reason why: for these graphs to work, you needed predictive odds that were broadly accepted and legal to use. Finance has always had them; elections have polling numbers to work with, so you could construct these probability paths Nate Silver-style. And sports seasons (or even individual games) have well-understood structures and enough historical data to confidently predict a team’s midseason odds of reaching the playoffs. These aside, the format of “story shapes” could not spread any more deeply into popular culture.

Prediction markets arrive, slowly

Prediction markets solve this problem in a fairly obvious way. As long as you can define a contract and the terms of its resolution, we now have a way for these “prediction shapes” to emerge about any story that’s going on in the world. Popular prediction – the required starter ingredient for this kind of story – goes from scarce to abundant.

In practice, these markets did not spring up overnight; not at first. In early 2024, the magazine Works in Progress published an article called “Why prediction markets aren’t popular.” The piece argued that there was “little natural demand for prediction market contracts,” since none of the three groups that classically make up market participants – savers (who seek to build wealth), gamblers (who make bets for thrills), and sharps (who seek to profit off the distortions caused by the former two groups) – have any particular reason to get involved in a prediction market. Savers who might buy a market index to build wealth over time have no reason to start betting on the outcome of a presidential election. Gamblers might be more inclined, but there are more interesting ways to speculate (day trading, memecoins, sports betting…) than making a prediction about the outcome of a state senate election. And with the other two groups having little involvement, sharps don’t see much money to be made by entering the market.

With sparse involvement from those three groups, prediction markets were fated to remain illiquid and relatively useless for predicting the future. The poor performance of prediction markets in predicting the outcome of the 2022 midterm elections lent credence to this view.

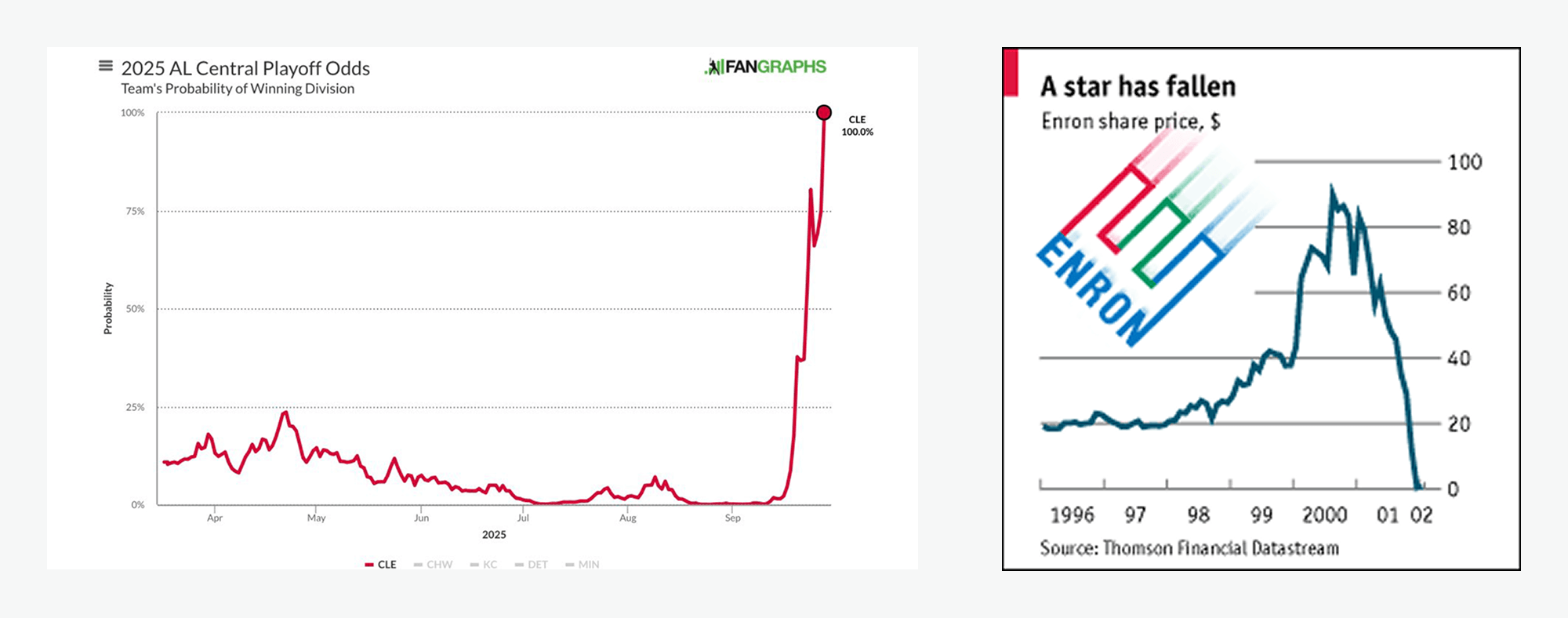

But in the year-and-a-half since that article was published, something interesting has happened: prediction markets have surged into mainstream popularity. As one might predict from the massive volume bet on sports each week, the largest markets are in sports. But they’ve managed to surge into mainstream popularity – enough to be the subject of a South Park episode – while hosting markets on everything from the results of the New York City mayoral election to the path of Federal Reserve policy rates to the time period in which Taylor Swift will get married.

The fourth wall breaks

What changed, if anything, over the past two years? There probably wasn’t one silver bullet. The 2024 election definitely helped: Americans have a long history of betting on elections, and prediction market volume grew 42-fold between early June and the week of the election. But it didn’t fade once the campaign was over.

The key actor in this positive feedback cycle was a new type of market participant, one that didn’t exist a few years ago but is now everywhere. This participant is similar to the promoters that you see in traditional betting events, like a boxing match in Las Vegas. It’s the humble, ordinary social media poster: and the new meme format of posting prediction paths as screenshots.

Prediction markets are now as much about social media-driven virality as they are about the classic dynamics of the market. The critical behavior mechanism is posting screenshots of the betting contract at the moment it becomes topically interesting, drawing awareness and liquidity into the contract.

For a great example, look at this Kalshi contract for the pop culture question of the year: “Will Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce get married in 2025?” If you look at the chart, you’ll see two important things happen on August 26th, when Swift and Kelce announced their engagement on Instagram. First, a spike in the odds; and second, a huge increase in liquidity as people start paying attention to the contract. While some amount of the liquidity jolt would’ve arrived regardless, there’s no doubt that these shared screenshots, at critical moments, constitute viral awareness of the contract itself, and a top-of-funnel draw into the bet. This kind of “fourth wall break,” where the broader audience suddenly gains awareness of the meme (or, more properly, of the reason to care about the contract at all), will give an interesting new meta element to future stories.

A new kind of Main Character for the timeline

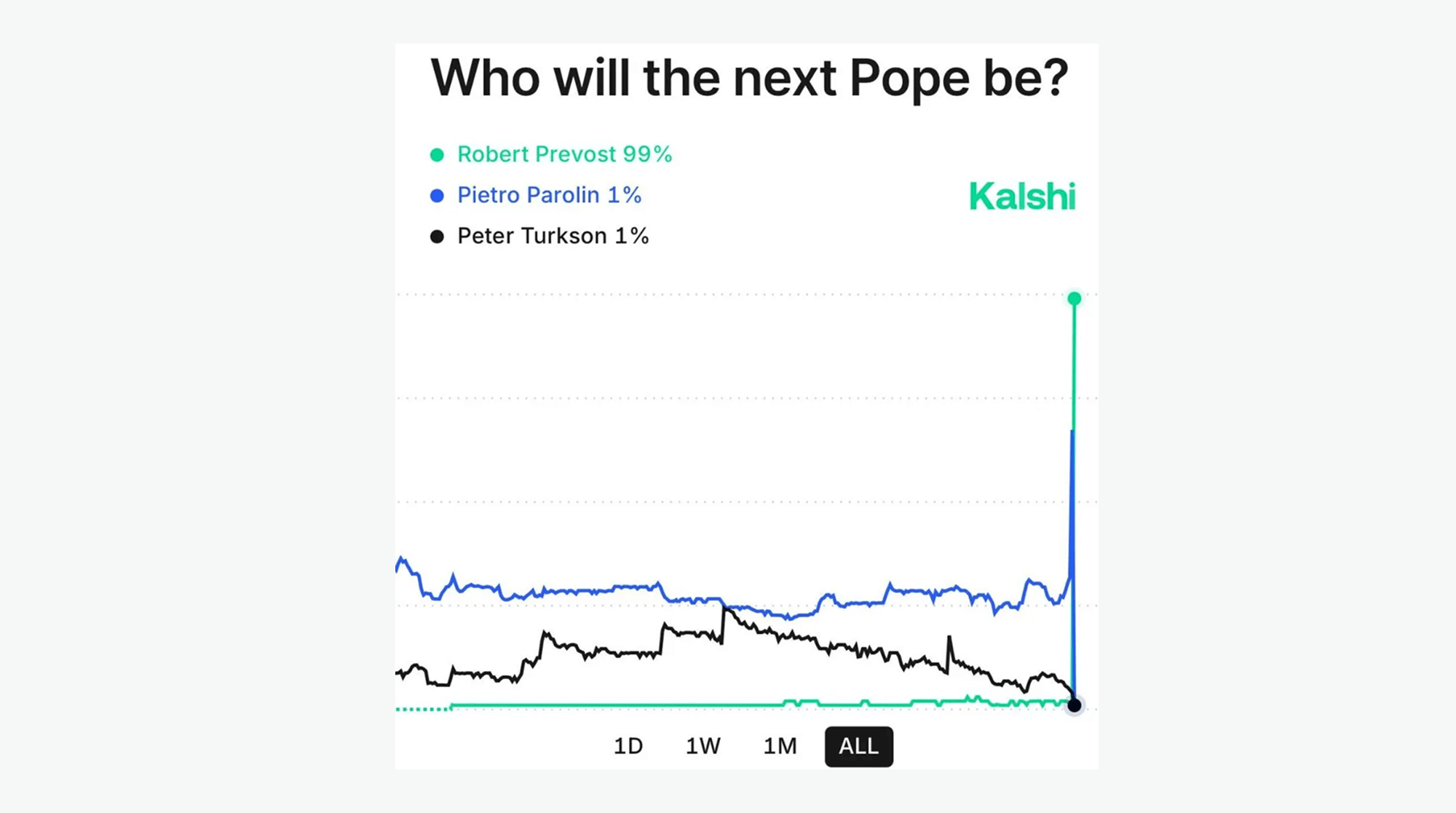

Betting on the Pope was supposedly the “original prediction market”, and this most recent time around saw a glorious return to that tradition. It was a great moment for Catholics around the world, as Cardinal Robert Prevost assumed the first American Papacy, as Pope Leo XIV. And it was a great moment for betting markets too, as few people had considered him a viable candidate: most of the attention had been focused on frontrunners like Pietro Paolin and Luis Antonio Tagle.

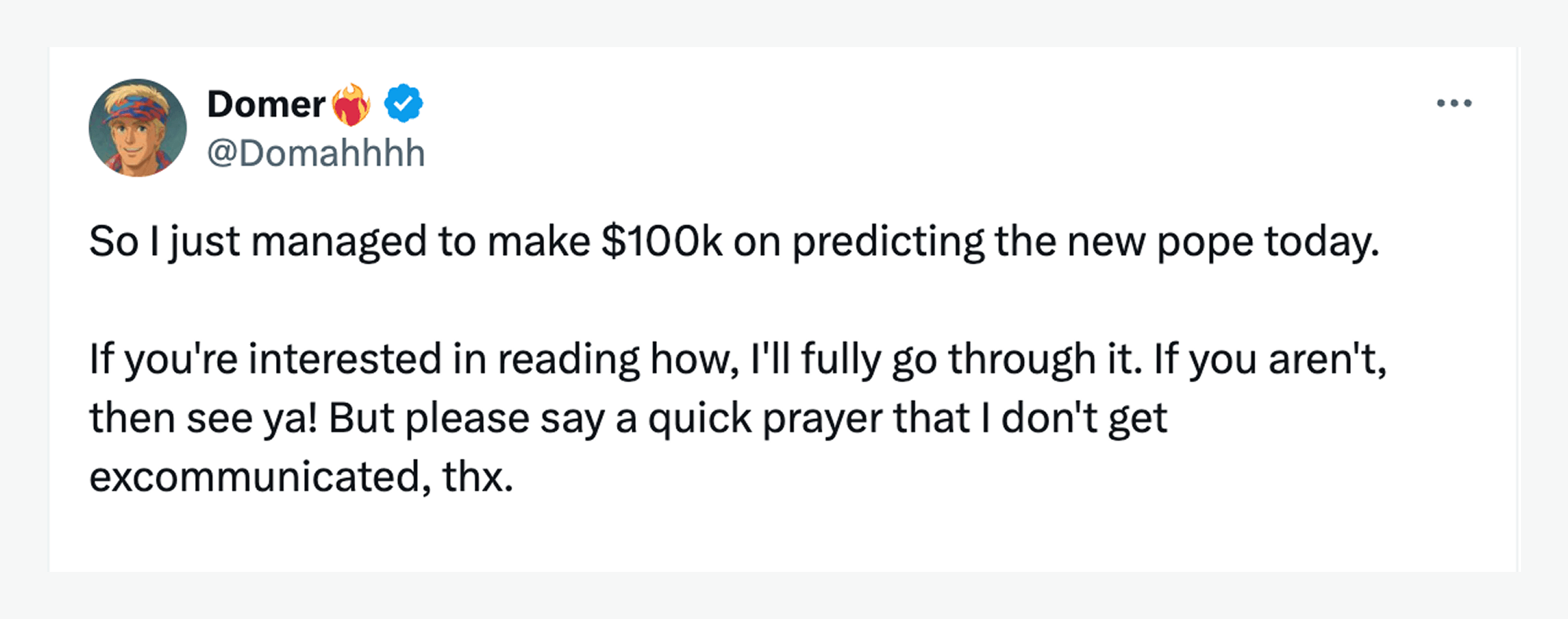

A day after the white smoke cleared, @Domahhhh on X shared a real gem with the timeline: the play-by-play breakdown of his thought process and his bet sizing, in both the days leading up to conclave and in the critical minutes between the decision and the reveal.

In his words: “As a directional bet, I decided to just bet a ton that the next Pope would be someone other than [Parolin and Tagle, the frontrunners].

The white smoke went up after the fourth ballot. This is, relatively speaking, fast. And the logical conclusion (and one that I immediately jumped to) is that this means a strong vote getter from the 1st round has consolidated the vote and become Pope. Parolin went to ~65%. Tagle stayed around ~20%. These two were 85% to be Pope, and tbh even though that price was incredibly wrong in hindsight, it’s hard to think it’s THAT wrong in the moment. I was convinced I had lost a lot of money! I decided not to chase good money after bad, and not to bet more against Tagle/Parolin. I would accept my loss like a good little boy.

But what I DID do is scroll through the list of other options. When you have two people now trading at 85%+, everyone else is in the clearance aisle. And I went rummaging in the bargain bin, and found Turkson at 100-1 and Prevost at 200-1. In hindsight, I should’ve also bought Grech at whatever he was at.

I knew one piece of information: it was four ballots. It’s too quick for a longshot. Throw all the longshot lottery tickets straight into the garbage. You need someone with gravitas, who is capable of capatulting to 2/3rd in a relatively short time period. And those two were the ones I picked out. I bought thousands of shares of each of them as other traders were focused on Tagle/Parolin.

A few minutes later, my jaw dropped as Prevost — the guy I had just amasssed shares in at 200-1 like 20 minutes earlier– walked out onto the balcony as Pope.”

There used to be this joke, “Every day on the timeline there’s one main character, and the goal is to never be it.” This kind of “victorious prediction poster” is a new kind of main character that gets to be a momentary certified hero.

Skin in the Game

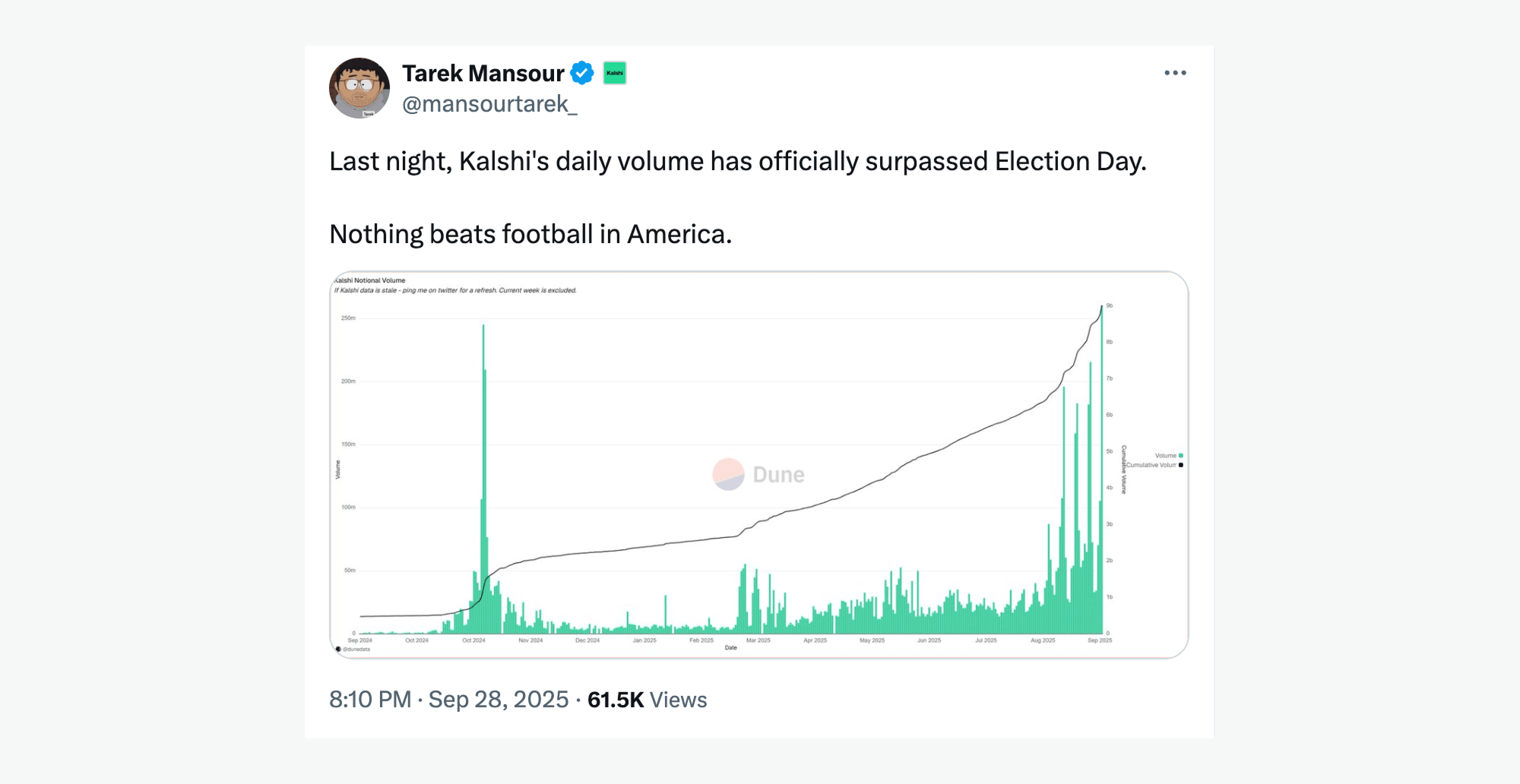

The 2024 presidential election gave prediction markets a well-deserved redemption story. It started with the prolonged saga that ended with Biden dropping out, during which prediction markets offered a useful quantification of how various events affected the odds of the president leaving the race. Everyone from journalists to Wall Street traders began to lean on prediction markets along with the traditional tools of polls and punditry. Ultimately, the prediction markets – criticized throughout the campaign for the alleged influence of “whale” traders – beat the polls. And nearly a year later, Kalshi daily volume now exceeds the 2024 election (during football games, at least).

Prediction markets now stand for something important, beyond their utility as financial instruments or information sources. They stand for a kind of accountability, and for a new kind of character on the timeline: “the hero that made the brave call,” “the idiot that made the bad one”. These people, now brought to the forefront as Vonnegut caricatures, as if it were one of his short stories.

In all kinds of walks of life, from politics to business to culture, we ask that our leaders and our public figures actually lead our institutions to successful futures. And that means making gutsy calls that turn out right. For the past few decades, there’s a popular sense that we’ve slid into a culture of unaccountability among some of those leaders, and we appreciate all the more when individual people step up and buck that trend.

That, perhaps, is the main mechanism by which prediction markets are set to alter the course of popular culture: not only because betting itself is an information flow that directs attention where it’s needed, but because the path taken by a prediction from inception to finish brings new memes onto the timeline, and new characters into relief.