Read more: Kalshi raises at $300M, led by a16z

Prediction markets have product-moment fit: they’re perfectly suited for the zeitgeist right now. And I think they carry a torch for a much bigger movement than what you see at face value. “Prediction” is now the entire game. It is the movement and meta-aesthetic that defines our main branch of society going forward; about how we interpret the world and participate in it.

Prediction is as significant a concept as modernism and postmodernism. It’s the defining reframe of our generation, and we’d better understand it:

- Postmodernism was why we built businesses the way we currently do: why we treat innovation as “capital at risk”, why we have the “front end / back end” service model, and other themes that are so pervasive they’re invisible.

- “Prediction” is a distinct break from postmodernism. It is what comes next.

- It can be hard to tell, in the moment, whether you’re looking at the beginning of something or the end of something. Many early AI artifacts that we think are “the future” are actually the final form of the old thing, rendered perfectly at their moment of obsolescence.

- All value creation now is about prediction.

- Prediction markets give us a unit we can understand, like how patents represented progress a century ago, that organized our ambition and represented a stake in the system.

- Prediction helps us break free from postmodern malaise, and gives us a new purpose in the world: we create order in the universe by contributing information.

Postmodernism and its native business model

Our current nostalgia for a time “back when we built things” draws much of its aesthetic from a movement called Modernism, which was the main thing going on in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We call them “movements” because they are truly grand ideas: multi-decade patterns of perceiving and thinking about art forms, business forms, and national forms; asking, “what is going on here?” at the highest level we can.

Peak modernism was about nation-states asserting their dominance as the new form of human identity and organization. The old multi-ethnic empires like the Habsburgs and Ottomans were dying; art movements like the Romantic period celebrated “unified” peoples, languages, aesthetics, and shared histories. This was a period of time where things in the world were the sum of their parts. We thought about one national heritage, or one body of science.

Nothing lasts forever, and Modernism certainly didn’t. After the pain of the World Wars, we retired that mindset for a subjective one, where identity is “rendered” case by case. Where modernism was about cause, postmodernism emphasized combinatorics: the thing you see is one arrangement of pieces; the thing I see may be another. That’s how we got Freud’s ego-self as a surface rendering of subconscious drives, defining art like Glenn Gould’s Goldberg Variations, and McKinsey. To experience peak postmodernism, watch Friends – first without the laugh track (the pieces themselves) and then with it (the rendered product). If you’d prefer, you can watch any episode of reality TV, or pro wrestling. It’s all the same.

Postmodernism quickly figured out its business model: the “front of house / back of house” abstraction of cost-effective, personalized service at scale. My favourite essay on this is Venkatesh Rao’s The American Cloud, on the Great Back End (the enormous logistical enterprise, hidden from view, that grows our food and heats our homes) becoming abstracted out of view, while coastal consumers interact with pleasantly recreated “situations”, like Starbucks or Whole Foods.

This idea was so powerful that its best biographers were its Marxist critics. In Postmodernism: or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, Fredric Jameson wrote in a tone that’s so frustrated it betrays a hint of admiration: “Aesthetic production today has become integrated into commodity production generally: the frantic economic urgency of producing fresh waves of even more novel-seeming goods (from clothing to airplanes), at ever greater rates of turnover, now assigns an increasingly essential structural function and position to aesthetic innovation and experimentation.” This is almost a sentence you could find in Atul Gawande’s completely sincere article about why hospitals should operate more like The Cheesecake Factory. It could also describe mobile app development. There’s one coherent idea through it all: the meaning of things is how they’re rendered-for-purpose.

From “progress” to “innovation”

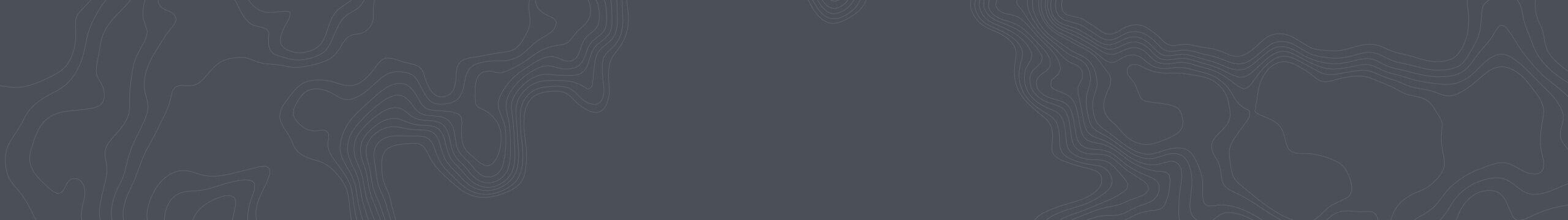

Modern and postmodern actors think about progress in very different ways. Modernism understood progress as something that simply happened; perpetually and unstoppably. And that way of thinking about the world became a self-fulfilling prophecy: the early 20th century delivered on those promises, as houses lit up with electricity and living standards shot up everywhere. Then in the middle of the 20th century, something interesting happened: we stopped talking about “progress”, and found a new word, “innovation”.

(Playing around on Google ngram)

In earlier times, “progress” came from either sheer force of will, or from luck (fortuna). But innovation is a postmodern concept: it reorients our goals into units of risk to be assessed, and prudently taken. Forward motion now happens in parallel expeditions, from measured acceptance of capital-at-risk. We rendered the potential out of a combination of bets, into a useful product. In 1957, Peter Drucker wrote in Landmarks of Tomorrow: “Innovation is… a new view of the universe, as one of risk rather than of chance or of certainty. It is a new view of man’s role in the universe; he creates order by taking risks. And this means that innovation, rather than being an assertion of human power, is an acceptance of human responsibility.”

Drucker was not predicting the future; he was trying to describe the present accurately. But he captured the mindset that led Bell Labs and the early Venture Capitalists to seed the beginnings of the future; and for startups to become a financeable endeavour. This is a big part of why Silicon Valley was so aesthetically compatible with what was going on in the rest of the country. Trying lots of small bets, searching for product-market fit, and getting rich at IPO were all postmodern quests. They fit with the rest of what was on TV.

These days in tech, we don’t use the words “progress” or “innovation” as much as we used to. Nowadays we talk about technological adoption. Adoption isn’t a new word; it certainly existed before, but it used to mean something specific about consumer requirements; whereas now it means the entire thing. I think there’s a clue here in where we’re going: that the important essence is not how you choose to engage (the postmodern mindset), but rather when you engage with the snowball rolling down the hill.

Prediction in culture: “I want to feel something, even if it hurts”

Now that our history basics are out of the way, let’s actually talk about prediction; the movement that’s happening now.

“Prediction” has two essential characteristics. The first is what we mean when we talk about prediction markets, or honestly any market. Prediction is the action that markets perform, as information moves around society and directs attention and resources to attractive destinations. Where they go constitutes a kind of prediction. The second essential characteristic of prediction is that computers are getting good at it. Computers now provide a broadly available superstructure for, “given this chain of things, predict a good next thing”, which will keep improving.

With that in mind, let’s go to the present moment and describe some of what we see.

The first observation I will make about popular society is how suddenly and decisively our culture moved towards speculation; not only in stocks and sports betting but also more broadly in life. Meme stocks might only be a few years old, but popular culture preceded them by a decade when Home & Garden TV programming became entirely about house flipping. Large swaths of the population now buy into the idea of “making your own luck” as a more literal virtue than it used to be.

This matters because there is now a meta-awareness (or meta-fantasy?) among the general public that our limited capital and attention could, in fact, find better places to go. There’s a driving energy in this world that everyone is doing this; and therefore, our attention each moment “predicts” the next one in a real sense. Not just forecasting it, but also setting the path dependence that leads us down the road and to a conclusion.

The second observation that I’ll make is how much social media now feels the same way that buying stocks does. Checking if your post is performing feels the same as checking whether your stock is up or down, and that tells you something important about your relationship to both activities.

At the forefront of culture and commerce, flash sales and popup stores are a revealing break from business convention where removing friction is always good. A sneaker drop is all about adding friction to the sales process. That’s why people like them: your place in line is the meaning of the product. Gaming predicted all of this, of course: that’s an industry that completely understands that friction is the product, and anticipation is consumption. The meaning of the game is the path you take through it, trying to feel something.

How early or late you are to something is now an essential component of your relationship to that thing. The timelines and reels that represent “what is going on” are increasingly about a single meta-topic: are you predicting it, or is it predicting you? This has become the main thing that you feel. And it is a complete break from the postmodern aesthetic, where your consumption was wrapped in an unthreatening fuzzy blanket. It doesn’t matter what time of year you arrive at Whole Foods to buy strawberries; the farmstand simulacra is recreated faithfully. The prediction aesthetic is a new thing, and rejects postmodernism: “I want to feel something, even if it hurts.”

“Is this art?”

It can sometimes be hard to tell whether you’re looking at the beginning of something, or at the end of something. In 2008 it sure felt like Obama was the beginning of something significant, but in hindsight he was actually the last president of the 20th century. Similarly, I think many of us thought the scrolling timeline feed was what came after newspapers; but in hindsight, the feed may be the last newspaper.

I remember the moment when AI generated art suddenly burst into public consciousness with Dall-E and Midjourney, and everyone gasped, “this is the beginning of a completely new kind of art!” I think with hindsight we will look at it with nostalgia, because it’ll actually be the last postmodern visual art form. It’s the final, perfect form of “everyone gets to consume the version they would like!”, at the moment it became culturally obsolete.

On that note, you’ll remember a lot of freakout at that time, “In the future, everyone is going to get their own personalized echo chamber of AI-generated news!” which is 1) not what’s happening, and 2) clearly our projection of our anxiety onto the old form factor and its problems. What’s actually much closer to happening is, “Everyone is going to have their own personalized parlay on the same series of reference events.”

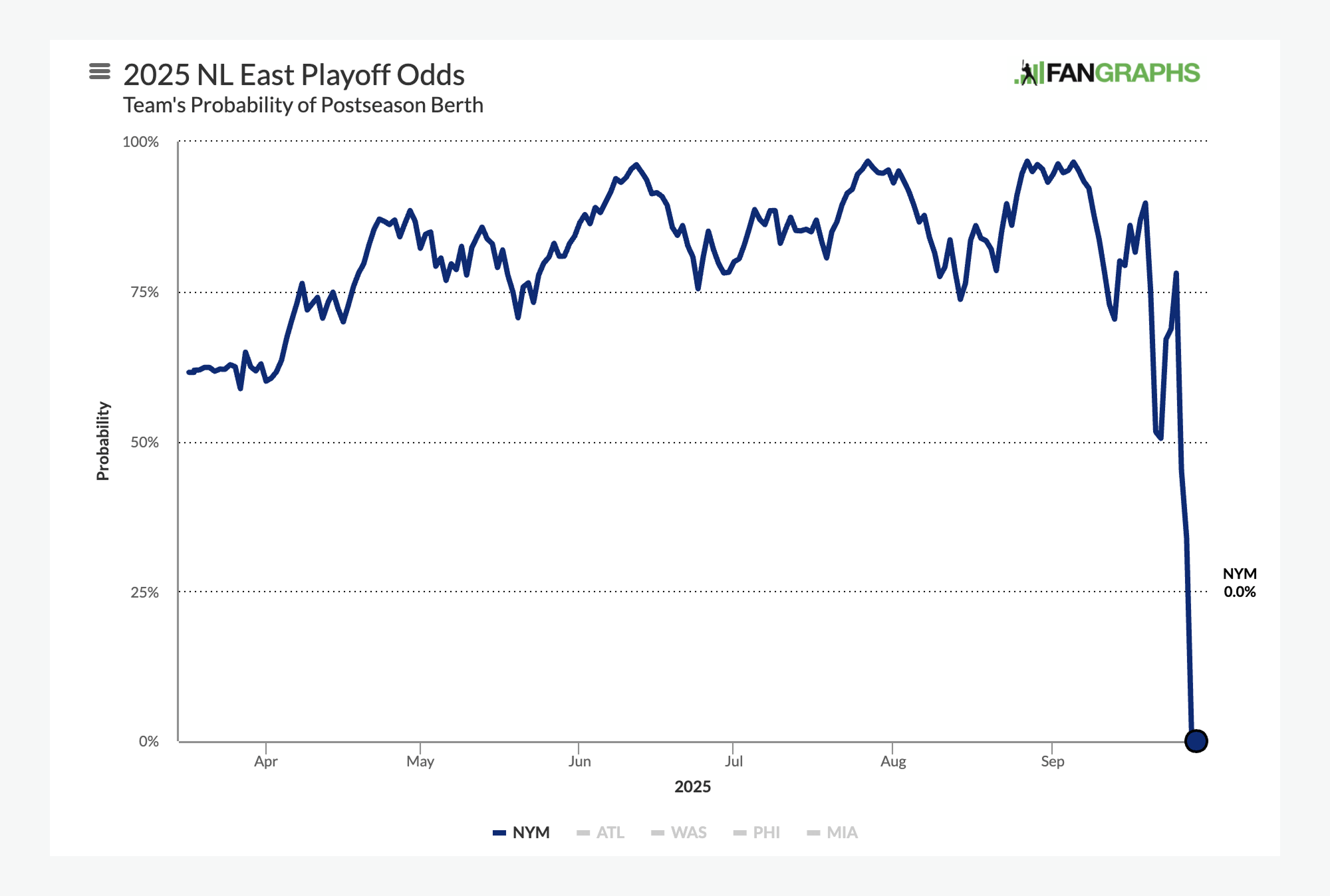

So what is an actually new art form? I don’t consider myself a contemporary art connoisseur, but I am pretty online. And there’s a definite art form emerging, which is public predictions that go really well or really badly. For example, this was art:

(If you don’t immediately recognize what this is – it’s a couple who dressed up as Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce for Halloween in 2020, who captioned their Instagram, “I don’t know any world in which Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce would be in the same room together. But apparently in this one they’re married?”) This post, now virally resurfaced, is certified pop art.

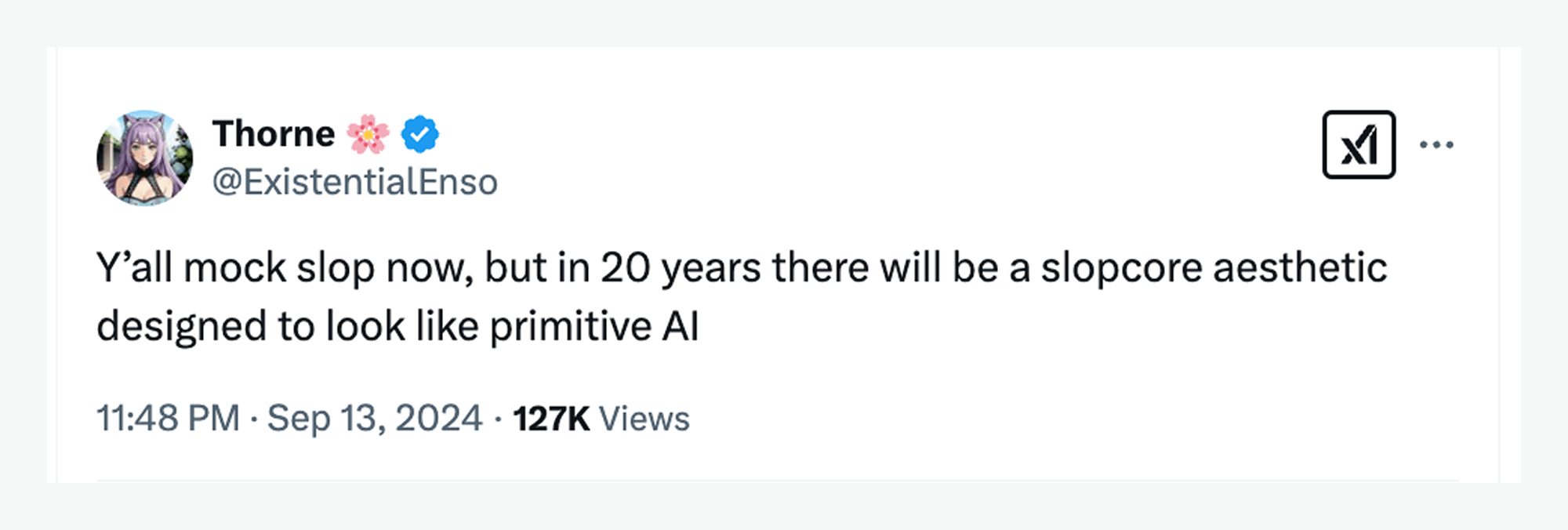

Another kind of art, which may make you mad, is NFTs and even more so Meme Coins. Because, 1) if suggesting something is art makes people Rite of Spring-level furious, you have something interesting; and 2), because they are a pure demonstration of public predictions as art, and the meaning of a thing being when you interact with it.

For example:

That’s art! Andy Warhol famously quipped of the postmodern era, “Everyone gets their 15 minutes of fame.” Today, I think it’s, “Everyone gets one 15-bagger.”

There also doesn’t necessarily need to be a prediction made, per se, to qualify as this kind of art. Just the prediction path itself is sometimes all you need:

Better luck next year, Steve Cohen.

READ MORE: Prediction Path Screenshots: a New Kind of Meme

Value creation in the Predictive Era

Every era finds a defining business model. For the modern period, it would be the vertically integrated giants that decided wars. For the postmodern period, it’s the front-of-house, back-of-house simulacrum. Our job today is to imagine what forms of business naturally resonate with where our cultural aesthetic is going.

Crypto was really avant-garde here, because they had to argue with everyone, “Onchain isn’t in the front end or the back end, it’s this new third thing”, that was hard for us to put into words, especially for practical app-building purposes. Culturally speaking, the proposition remains: “for every piece of content, there is now a publicly viewable timeline for whether you own the content or not, and when you bought and sold it”, which produces very silly results when taken at face value, but contains a critical insight. Which is, “We’re all participating in one great online game, and your goal is to be predictive of the game, rather than predicted by the game.”

But the real party started when LLMs became a product in their own right, and suddenly this nebulous thing called “weights” became the most sought-after asset in the world. As AI models start contributing to business decisions, showing ads, and influencing the culture, we now have a tangible place where “everyone has their own personalized parlay on the same series of reference events” is now no longer about gambling; it’s about the whole timeline of your life. And in many cases, the house is actually trying to help you win.

“Gen” was the best word I could find at the time; “Prediction” is much better.

I think back on Packy’s Great Online Game piece a lot, because this was a piece that was basically about training LLMs, except for it was written in 2021, about ZIRP Online Citizenry. “Being good at the Internet” is now a highly practical and monetizable career – it used to be, too, but less legibly. Today, it’s easier to understand why being online is naturally monetizable: because prediction is it; prediction is the entire meta-game, from meme coins to model training, and the farther upstream you are in the information flow, the more likely you’ll be predictive of the game as opposed to being predicted by the game. It is suddenly not-so-ridiculous when Matthew Prince of Cloudflare asserts, “the way you’ll get paid on the internet now is by writing things that the AI does not yet know.” We’re not there yet, but there is a plausible path to it.

Meanwhile, the institutions of the future are getting built in a Venture Capital environment today that has completely embraced and assimilated into the new prediction movement. The old days where you ran a fixed fund size and accumulated early stakes in a single-stage portfolio may still work on rare occasions, but it’s definitely passé. Today, everything is about multi-stage continuity, and whether you’re on the predictive path.

Prediction contracts as the atomic unit

Every builder paradigm comes with its own financial instrument; its own way of capturing potential into an ownable, tradeable thing. The most important one of these in the modernist era was the patent. Patents did much more than legally protect an innovation and help them monetize: they also captured the imagination of the public, and became an “instrument of progress” that you could name and appreciate. They encapsulated the thinking of the time, defining an invention as literally the sum of its parts. “Parts” could mean physical components or mechanical processes or other contributing methods, but whatever they were, a patent encapsulated them all into a unitary invention.

Once the broad public came to associate patents with invention, they became what invention was, in a self-fulfilling prophecy. In time this became a bad thing, as universities and researchers overrotated on “produce and monetize patents” to the detriment of actual progress. But for a long time, having a single idea that you could associate with invention was almost certainly a net positive. Patents inspired people to think like inventors; they organized our abilities, and set a bar you needed to achieve. They were a stand-in for “progress” in our modern perception of the world.

I wonder if prediction contracts might serve a similar purpose: as a centrally organizing idea, and commonly accepted format, for the incredibly broad concept of “prediction” that’s so important to our main thread. Being a live player means making predictions. “Putting your money where your mouth is”, and actually committing to a prediction, feels like a new form of, “Oh so you think you invented something? Patent it!” and that’s a good thing. Especially considering that patents were only something a few people ever accomplished, whereas anyone can participate in a prediction contract, and in their own little way, contribute.

Our purpose in the world is to contribute information

We may soon arrive in a world where intelligent machines are conceiving, driving, and implementing a lot of our material progress. They’ll be making scientific discoveries, recursively designing new robots, and who knows what else. That’s a great thing. We’ll take all the progress we can get.

But it is essential that people in the world feel like they have a stake in the system; like they’ve contributed to our shared sense of progress. And I believe Predictions, as a movement, are the answer to our postmodern malaise. They give us something to do.

I see no better explanation for the rise of speculation, gambling, and public prediction in the last ten years of popular culture than as a mass revolt against the numbing apathy of late postmodernism. And even though I find some of it uncouth and crass, I don’t see it as a regression: it’s a step forward, in self-discovery. We have a new way to think about our purpose in the world: we create order in the universe by contributing information. And in the past few years, we’ve discovered the extent to which it’s a shared purpose; perhaps a universal one. I couldn’t imagine something more optimistic if I tried.