Driving is a modern miracle. There is a reason why the car was the symbol of progress for much of the 20th century. No other piece of technology has shaped where and how we live, what real options we have in our life, and stood for upwardly mobile progress quite like the personal automobile.

Driving is a social achievement that’s just as impressive as the car was a technical accomplishment. The everyday coordination of millions of people moving around a city and a nation is a human triumph of emergent, learned behavior. The work of drivers seeing each other, yielding, passing, and offering each other mutual gifts of courtesy and safety is a social load that we have collectively learned to manage at scale.

Driving also has a human cost. My late grandmother used to say, “Cars are killing machines.”

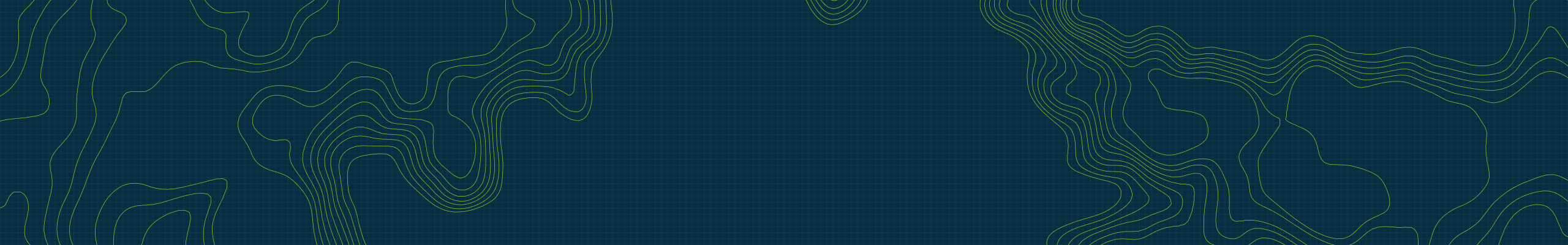

About 40,000 Americans die in crashes every year, with hundreds of thousands more injured. For young people, cars are right up there with guns and drugs as a cause of death. Globally, road collisions are responsible for 1.2 million lost lives and the #1 killer of people aged 5 to 29.

We had been making remarkable social progress on this problem, year in and year out, for decades. Seatbelts, crumple zones, airbags, drunk-driving enforcement, just plain better driving standards—year after year, per-mile deaths went down. But then something happened. A new, competing social technology arrived; and for all its benefits to the world, it was not good for driving safety at all. That technology was the smartphone.

Social robots to the rescue

The smartphone has arrested and reversed our decade-long social accomplishment of safer driving. It is a competing social technology. It competes for your attention, for your eyes, and for your focus. Even when your phone is face down in your cupholder, it’s still in your head: email, messaging, social media, remains distracting even when kept at distance. We’ve wired our entire economy and social lives into a little slab of glass, and then we tell people to completely ignore it when they pilot two tons of metal on the highway.

The crux of the problem is that phones have completely changed the composition and distribution of social load in society. They change how and when we have capacity to handle social load, and they change where we want to deploy it. For all we pro-technology people celebrate the new ways in which people communicate and create with each other, we have to acknowledge the fact that the social system of driving has silently borne the cost of this change. Driving has become deadlier, angrier, and less forgiving since the smartphone. And we’re not going back to a pre-phone era, so something has to change.

Cars are great, smartphones are also great, but zero sum between them is bad.

Just in time, another technological revolution is coming to the rescue: autonomous vehicles. Autonomous vehicles are not just “driverless cars”, they are social robots. They don’t just turn the steering wheel and move the pedals; they do a social kind of work that we have less capacity for in our new world of phones and internet. This is an even more incredible triumph of human ingenuity than we give it credit for. We’ve invented a machine that happily, willingly, and flawlessly handles some of the most human work imaginable, in the most positive-sum way you could ever ask for.

Driving is a conversation, literally

It’s been thirty years since the first car “drove itself autonomously” coast to coast across the United States… 98% of the way. We’ve always known that the last 2% of driving, whether by road miles or by seconds of attention or however you want to measure it, would take decades to figure out. But sure enough, we did. It took layers of innovation – from better machine learning models to better sensors like LIDAR and even better ways of building consumer-facing tech companies themselves – to get to Waymo. But now it’s here! Really it’s been here for 15 years, just quietly getting the last details right, until its public debut in 2018 and ever since.

Earlier this year, Vincent Vanhoucke from Waymo explained the degree to which the last 2% of driving was really a triumph of social technology. Autonomous cars, in a literal sense, have had to learn how to have conversations with other agents in the world, where that conversation takes place through iterative actions:

“Driving is inherently a social thing. What’s interesting is, we tend to model those interactions as little bits of conversations, literally. It’s visual movement conversations. I move forward; what does this other car do? This car stops; okay, I can go. This car goes; I’m gonna have to stop. It’s literally modeled as a visual motion conversation; very similar to what you would do with conversational agents. So there are lots of parallels between the conversational AI and the autonomous driving problem that we can leverage and learn from.”

What has really closed the gap in that last 2% of miles driven is cars learning the traffic equivalent of “being able to to talk and listen.” That ability to reason and communicate on the fly, about novel situations given very human cues, is the technological gap that had been missing, and the technological work that can now be done by autonomous vehicles. As an example, cars have to learn that when a construction worker puts up their hand it means “stop”, but if they put up their hand with their fingers curled a tiny bit, it might mean go – but the car has to communicate with that worker to safely validate its choice before accelerating through what might be a misunderstood and therefore deadly situation.

The fact that cars can now do this safely – without ever getting tired, or frustrated, or annoyed – is a triumph of the social robots. And it is incredibly encouraging in how it shows the way forward for humans to actually get along well with our new intelligent companions.

What are we waiting for?

Today I have a not-yet-two-year-old son, and my main job is to keep him alive. My quiet hope is that by the time he’s old enough to drive, he won’t need to. “Driving a car” will sound to him the way “riding a horse to work” sounds to us.

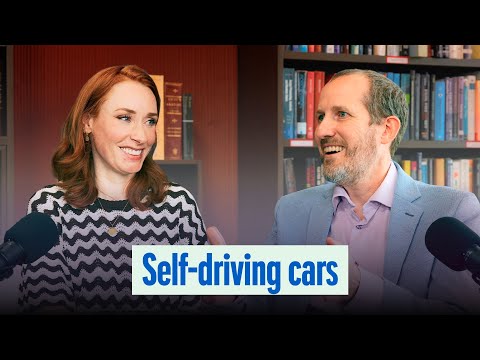

In June 2025, Waymo published its safety impact comparing its rider-only program to human drivers. The headline stats should be surfaced on billboards: 90% fewer crashes that cause serious injury or worse, and 81% fewer crashes that cause any injury at all.

As Dr. Jonathan Slotkin pointed out in his NY Times guest essay, there’s a medical research practice of ending studies early when there’s overwhelming benefit such that it would be unethical to continue giving anyone a placebo. Human driving is a placebo; self-driving is the drug. If a new drug reduced heart attack deaths by 80-90%, we wouldn’t debate the comfort of patients; you would fast track it.

Waymo’s are not perfect. There have been software recalls. But they are much safer than us. This is not 5-10% better. This is an 80-95% reduction in the bad outcomes we actually care about: people going to the hospital; people not coming home.

If you live in the Bay Area, you can pull out your phone and choose between a Waymo and a human-driven Uber or Lyft. Given what we now know, if you have that choice, it is increasingly hard to justify picking the human driver. And we should thank our local leadership that they have allowed this choice to be available to us at all. It is ridiculous and frustrating that not all local leadership feels this way.

When cities and states drag their feet on adopting autonomous driving, they are making a choice. They are choosing more funerals, more wheelchairs, more parents getting calls from ER doctors at 2 a.m. At some point, that’s not “caution.” That’s negligence. If a mayor blocks deployment of a system that cuts serious crashes by 80–90%, and people keep dying on those roads the old way, that should be treated as a moral crime.

The alternative is that we put these miraculous social robots to work for us. It is the most win-win situation you could ever have hoped for: social robots that save us time and save our lives, while getting constantly better at substituting for our social effort at a time where phones have completely rearranged how and where we can direct our energy. Cities and states should compete to be first in line for autonomous vehicles. The US pre-paid to get first access to COVID vaccines when the evidence was far less mature than what we have for autonomous vehicles. Autonomous vehicles should be a core campaign plank, right alongside housing, healthcare, and education.

If an autonomous driving system can show, with independently auditable data, that it produces dramatically fewer serious crashes per mile than human drivers on the same roads, let it scale. Today Waymo is leading the way, but if and when other providers – Tesla, Zoox, Wayve, Applied Intuition, whoever – can clear the performance-based standard, the more the better.

We credit Waymo as a technological triumph, and autonomous vehicles as a feat of computer vision and engineering, but really they’re even more significant than that. They are the first example of robots stepping in to do an incredibly human kind of work that saves lives as an added bonus, and as an extra incentive to get them everywhere as quickly as possible. If you’ve ever wondered what the catalyst will be that gets humans ideologically comfortable, grateful, and happy to live alongside our social robot friends, you don’t have to look far to the future. You can see it today: just look for a Waymo.

Cars are killing machines, but they don’t need to be.