Note: This essay is the first part of an ongoing series of insights and learnings from the State of AI report, powered by OpenRouter, an AI inference platform providing access to hundreds of models and real-world usage trends across the AI ecosystem.

MVPs, Churn, and the Old SaaS Playbook

In traditional SaaS, early retention is often a slog. The common playbook: ship a Minimum Viable Product that’s thin on features, then scramble to enrich it while hoping users stick around. Iterations are expected, even encouraged, in the early days. Founders cross their fingers that iterative improvements will win back the deserters or at least slow the leaky bucket.

This dynamic has defined SaaS for years. You launch with what you’ve got, watch many early adopters drift away, and iterate intensely to improve retention. Great retention is gold, but it’s notoriously hard to achieve out of the gate. As BK noted, “retention is the lifeblood of an app and the hardest metric to move”[2]. In the world of SaaS, initial user loss is almost a rite of passage: something to minimize, sure, but largely a reality you plan for.

But now, something strange and different is happening in the AI world. The old playbook is flipping. Instead of low early retention being the norm, we’re seeing some AI products achieve amazing retention from their very first cohorts of users as if those users found exactly what they were looking for and never left. It’s not happening for every AI product (far from it), but a new pattern is emerging that’s worth every founder’s attention. We’ve started calling it the Cinderella “Glass Slipper” effect, and it’s turning our understanding of user retention on its head.

A New AI Reality: When the Shoe Fits, Users Sit Tight

Why do some AI products defy the typical MVP-and-churn pattern? The answer lies in a hypothesis we dub the Cinderella Glass Slipper effect. The metaphor comes straight from the fairy tale: imagine a set of prospective “customers” (Cinderella herself, in our analogy) persistently trying on solution after solution, model after model, looking for the perfect fit. Most offerings are either too loose, too tight, or just not quite right for the job-to-be-done. These high-value problems, call them unsolved workloads, are like Cinderella’s foot, waiting for the glass slipper that fits just right.

In today’s frenzied AI landscape, developers are experimenting with a dizzying array of models. (As a data point, OpenRouter saw usage explode 10x, from 10 trillion to over 100 trillion tokens processed in just one year. New endpoints are being added daily.) With each release, teams quickly test: Does this new model solve my problem better? In many cases, the answer is “not really”, and so they churn, becoming AI “tourists” who try a product once and wander off. This is the norm: lots of excitement, brief experimentation, then on to the next thing.

But every so often, a new frontier model arrives that does solve a stubborn, high-value workload with uncanny precision. When that happens, it’s like finding Cinderella’s slipper. A specific cohort of users discovers a workload-model fit – a perfect alignment between what they desperately needed and what the AI delivers. These users don’t behave like typical early adopters who churn; instead, they dig in their heels. They integrate the model deeply into their product or workflow, invest significant engineering effort around it, and effectively lock in. After all, why switch if this model finally “fits” their use case like a glove?

We call these initial sticky users the foundational cohort. They often emerge right at launch, when the model is first heralded as state-of-the-art. They’re drawn by the promise of something fundamentally new, and if that promise is fulfilled, their retention is extraordinary. It’s as if the product didn’t just find a user base; it found its ideal user base immediately, on day one. This runs completely counter to the usual MVP story. In AI, an early cohort can exhibit better long-term retention than ones that come later.

Why would later users be less loyal? Because once the “glass slipper” cohort has found its fit, subsequent users are often more casually experimenting or have needs already met elsewhere. The model is no longer the shiny new frontier; it’s now one of many tools, and any unmet needs will prompt these later users to jump to the next model du jour. In contrast, the foundational cohort remains firmly planted, having found their perfect match.

Foundational Cohorts in Action: A Tale of Two Launches

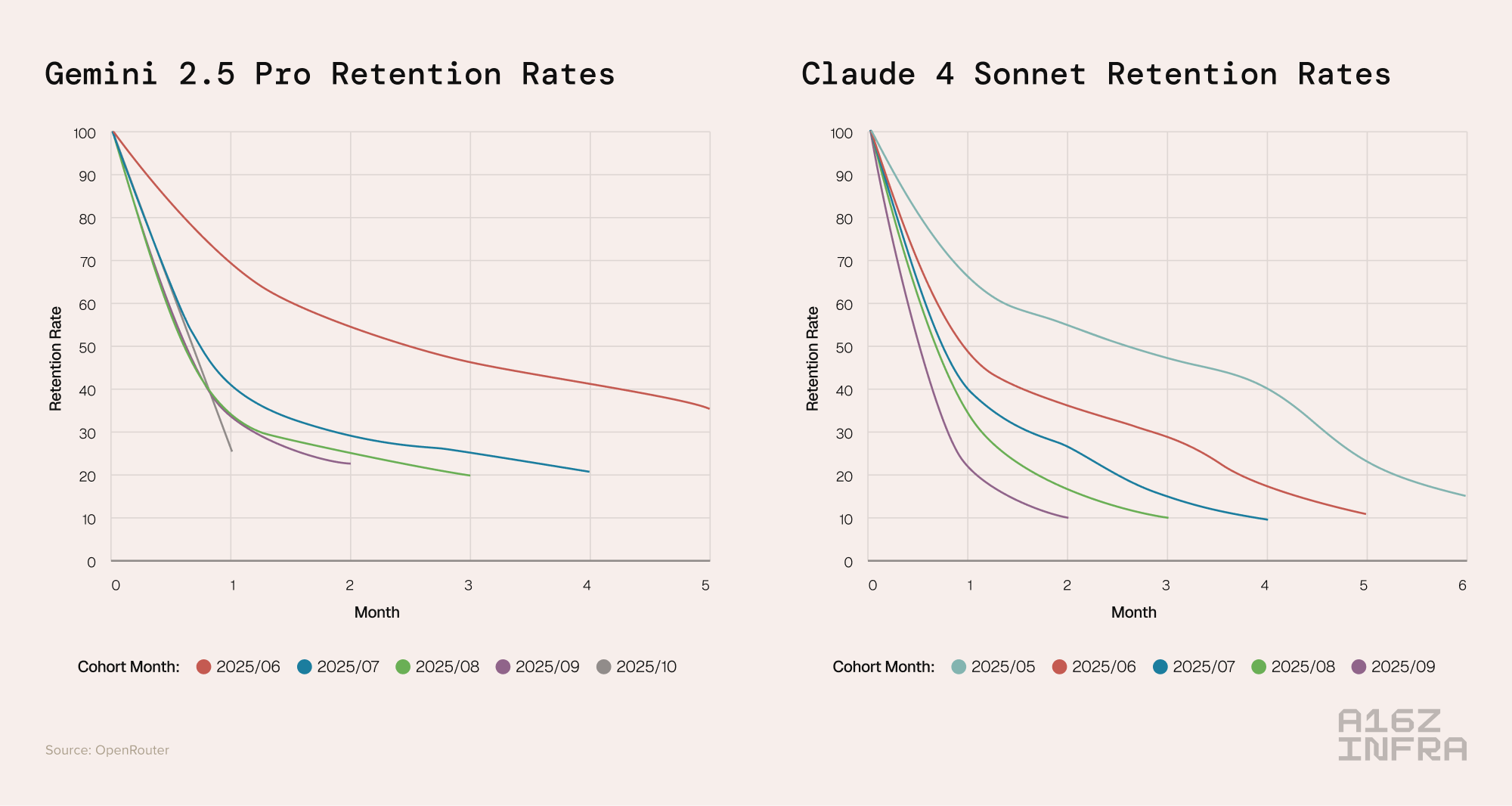

To see the Glass Slipper effect in action, look at recent AI model launches. We analyzed usage cohorts from the State of AI: An Empirical 100 Trillion Token Study with OpenRouter (a comprehensive look at real-world LLM usage via OpenRouter data). The retention curves tell a striking story. Each cohort represents users who started using a given model in a particular month, then shows what percentage of those users are still active in subsequent months (counting a user as “retained” if they come back in any later month, even after a gap).

Take Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro, a flagship model that debuted as a top-tier “frontier” model in mid-2025. Its June 2025 launch cohort stands out like a beacon: even 5 months later, almost 35% of that cohort was still actively using the model. This is remarkably high retention for a cohort of developers using a single model. It suggests that in June, a bunch of developers found exactly what they needed in Gemini 2.5 Pro, perhaps advanced coding capabilities or a leap in accuracy, and stuck with it.

Now compare that to cohorts that onboarded a few months later, say in September or October 2025. Those later cohorts churned much more heavily; their retention curves plunge toward the bottom, meaning nearly all those users disappeared in subsequent months. Why? By autumn 2025, Gemini 2.5 Pro was no longer the shiny new thing – newer models were on the horizon, and developers who hadn’t yet found a perfect fit were still shopping around. The foundational June cohort had already claimed the model’s prime use cases, and later users ended up being “explorers”. They tried Gemini 2.5 Pro, didn’t see a Cinderella-grade fit for their needs, and moved on.

We see a similar pattern with Anthropic’s Claude 4 Sonnet, another frontier model around the same time. Its May 2025 launch cohort retained roughly 40% of users by month 4, roughly the same as Gemini’s, but still a standout compared to later cohorts for Claude. Those May users apparently hit a sweet spot (perhaps Claude 4’s advanced reasoning or lengthy context window solved problems other models couldn’t). Later cohorts in the Claude 4 Sonnet chart tell a different tale: users coming in the fall churn faster, likely because Claude 4 was no longer unique by then and their unmet needs pushed them elsewhere.

In essence, when an AI model debuts with a clear technical edge, it has a brief window to hook a foundational cohort. In that window, which may only last until the next big model launch, the first users to “try on” the model either find a fit or they don’t. If they do, they become power users who keep the product alive (and keep usage high) long after the hype moves on. If they don’t… well, then every cohort after looks the same: fleeting and fickle.

When the Slipper Doesn’t Fit: Cautionary Tales

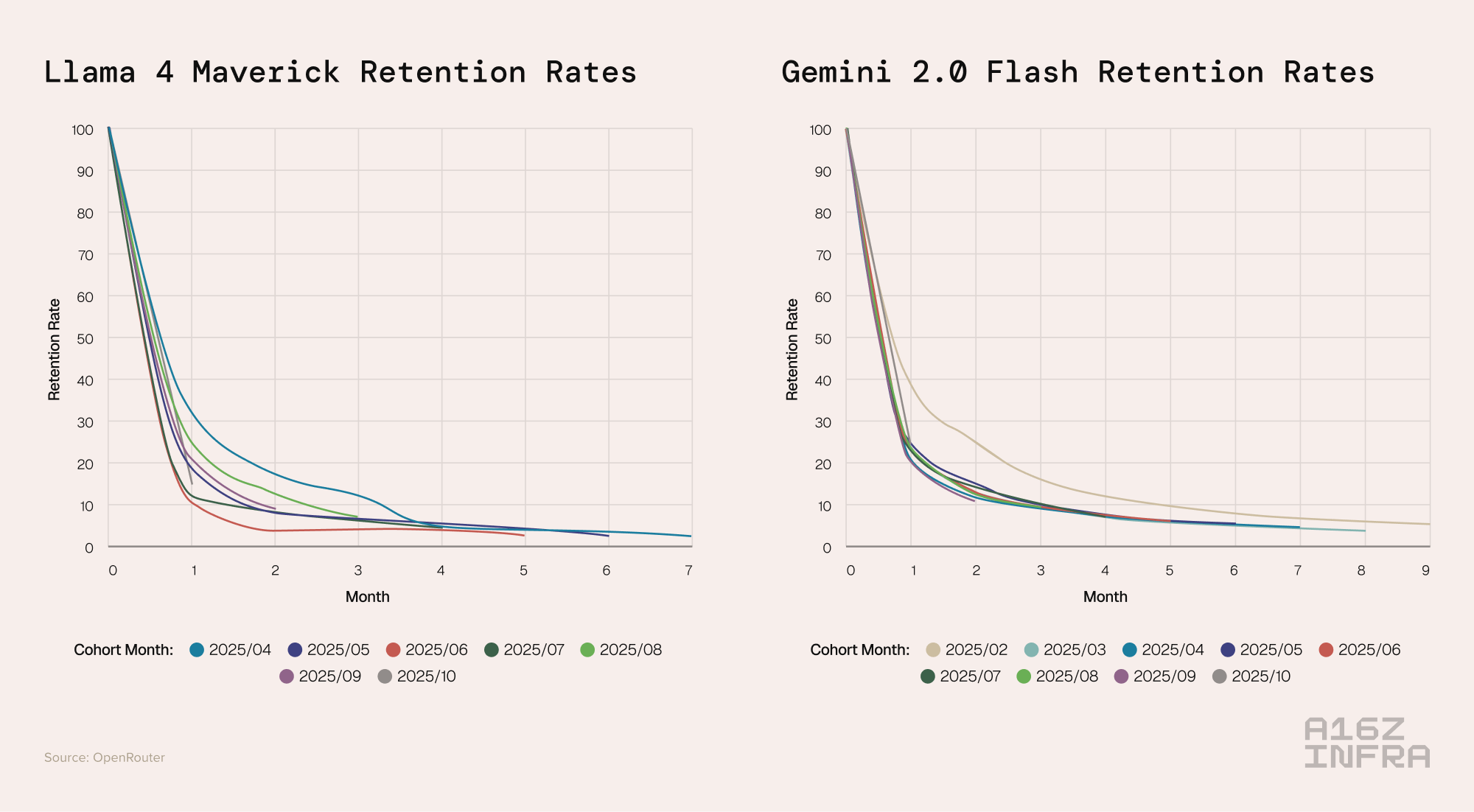

What happens if the “glass slipper” moment never comes? Unfortunately, we have examples of that too: models that launched without ever demonstrating a unique, sticky advantage. Their retention charts look like a pure commodity curve: every cohort behaving the same (and poorly at that).

Take Gemini 2.0 Flash (an earlier generation of Google’s model) or Llama 4 Maverick. These models burst onto the scene with decent capabilities, but not a clear frontier leap over incumbents. As a result, no cohort ever formed a durable attachment. Users came, played around, and churned at roughly equal rates whether they started in month 1 or month 10. The retention lines for each cohort overlap in a disheartening tangle near the bottom of the graph – no standouts, no foundational users. In plain terms, the product never found product-market fit. It launched directly into what we might call the “good-enough” market – a landscape where plenty of models could do an okay job, and none inspired great loyalty. Without being perceived as a category leader or solver of a new class of problems, these models failed to lock in any significant user base.

Why Foundational Cohorts Matter More Than Ever

In the era of rapidly advancing foundation models, the stakes around retention have changed. We’ve entered an age where AI capabilities leap forward in giant strides rather than baby steps. With each leap, there’s an opportunity to conquer new use cases: to be the first model that finally nails a task that was previously unsolved. And if you do, the users with that problem will flock to you and stay.

This “Cinderella” dynamic has huge implications for AI companies and investors:

- Product-Market Fit = Workload-Model Fit: In AI, achieving product-market fit may literally mean solving one high-value workload better than anyone else. It’s less about a broad feature set and more about depth on a critical dimension. When you hit that sweet spot, retention follows naturally as users finally get what they’ve long needed.

- First-Mover Advantage, Redefined: Being first to market isn’t always a guarantee of success – unless being first means being best at solving a pressing problem. The Glass Slipper effect suggests that the first model to achieve a new level of capability locks in the lion’s share of loyal users for that capability. Those users become very costly to pry away later, because they’ve now built workflows, businesses, and even mental habits around the model. Switching to a competitor model would incur retraining costs, quality risk, and engineering work – a high friction that keeps the original pair bonded. In business terms, this is classic lock-in driven by high switching costs. Once an AI model is deeply embedded, prying it out is as tough as forcing Cinderella’s shoe onto a different foot.

- Retention as a North Star Metric: In the gold rush of new AI tools, one might think growth (sign-ups, adoption) is everything. But smart founders will pay just as much attention to retention curves. Are there signs of a foundational cohort forming? Is there at least one user segment that finds your model indispensable? If you’re seeing all cohorts behave the same with quick drop-offs, that’s a red flag – you may need to double down on differentiation or target a more specific pain point. Conversely, if one cohort is retaining far better than the rest, study them. They are your glass slipper wearers, and understanding why your product fit their needs can guide your roadmap (and your pitch to investors).

- The Frontier Window Is Narrow: The data suggests that the market crown of “frontier model” is transient. Each new model is only considered frontier for a short window until the next contender arrives. This means AI companies have a brief period to capture those elusive foundational users. It’s a one-time opportunity to impress the hardest-to-impress users – those with unmet needs. Miss that window, and you’re fighting in the trenches of incremental improvements. For AI startups, this raises the pressure on launches: it’s close to being all or nothing. The upside of nailing it is huge (entrenched users, perhaps even a quasi-monopoly on a niche). The downside of a middling launch is steep churn and an uphill battle to differentiate later.

Conclusion: Building for the “Glass Slipper” Moment

The Cinderella Glass Slipper effect is more than a colorful metaphor. It’s a reflection of how AI is rewriting the rules of product adoption and retention. In a world where new models emerge constantly and developers can switch with a simple API call, user loyalty might seem fleeting. Yet, as we’ve seen, when an AI product truly meets a deep need, it creates fans, not tourists. Those early fans stick around through thick and thin, providing a foundation upon which entire businesses can be built.

For entrepreneurs and builders in AI, the mandate is clear: know the unsolved, high-value problems in your market. Aim to be the first to solve one of them completely, even if narrowly, rather than building a half-baked generalist that’s “good enough” in a crowded field. It’s the difference between being another shoe on the rack and being the glass slipper that perfectly fits the foot that’s been searching for it.

In the end, the story of AI’s next phase may not be just about whose model is bigger or faster. It may be written by those who can say, “We found the exact users who needed us, and they’re still with us, four months later.” That is the magic of a perfect fit.

For related reading on this topic:

Retention is all you need: a new gut-check for measuring AI companies’ retention | by Santiago Rodriguez & Alex Immerman, a16z