If you live in the United States today, and you accidentally knock a hole in your wall, it’s probably cheaper to buy a flatscreen TV and stick it in front of the hole, compared to hiring a handyman to fix your drywall. (Source: Marc Andreessen.) This seems insane; why?

Well, weird things happen to economies when you have huge bursts of productivity that are concentrated in one industry. Obviously, it’s great for that industry, because when the cost of something falls while its quality rises, we usually find a way to consume way more of that thing – creating a huge number of new jobs and new opportunities in this newly productive area.

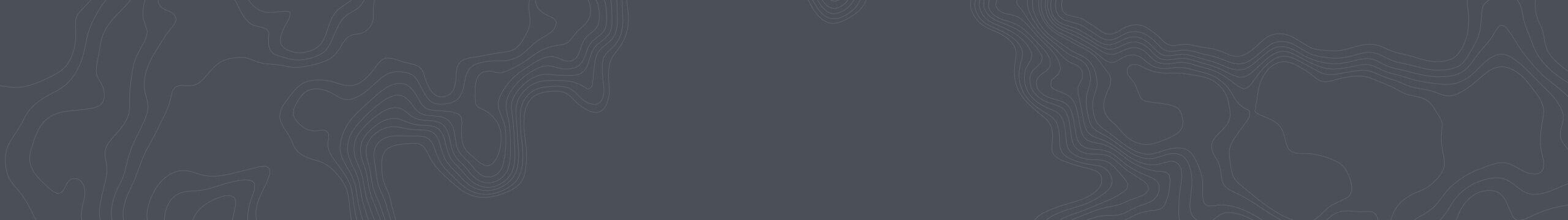

But there’s an interesting spillover effect. The more jobs and opportunities created by the productivity boom, the more wages increase in other industries, who at the end of the day all have to compete in the same labor market. If you can make $30 an hour as a digital freelance marketer (a job that did not exist a generation ago), then you won’t accept less than that from working in food service. And if you can make $150 an hour installing HVAC for data centres, you’re not going to accept less from doing home AC service.

This is a funny juxtaposition. Each of these phenomena have a name: there’s Jevon’s Paradox, which means, “We’ll spend more on what gets more productive”, and there’s the Baumol Effect, which means, “We’ll spend more on what doesn’t get more productive.” And both of them are top of mind right now, as we watch in awe at what is happening with AI Capex spend.

As today’s AI supercycle plays out, just like in productivity surges of past decades, we’re likely going to see something really interesting happen:

- Some goods and services, where AI has relatively more impact and we’re able to consume 10x more of them along some dimension, will become orders of magnitude cheaper.

- Other goods and services, where AI has relatively less impact, will become more expensive – and we’ll consume more of them anyway.

And, even weirder, we may see this effect happen within a single job:

- Some parts of the job, automated by AI, will see 10x throughput at 10x the quality, while

- Other parts of the job – the part that must be done by the human – will be the reason you’re getting paid, command a wildly high wage, and be the target of regulatory protection.

Let’s dive in:

Jevon’s: Productivity gains that grow the pie

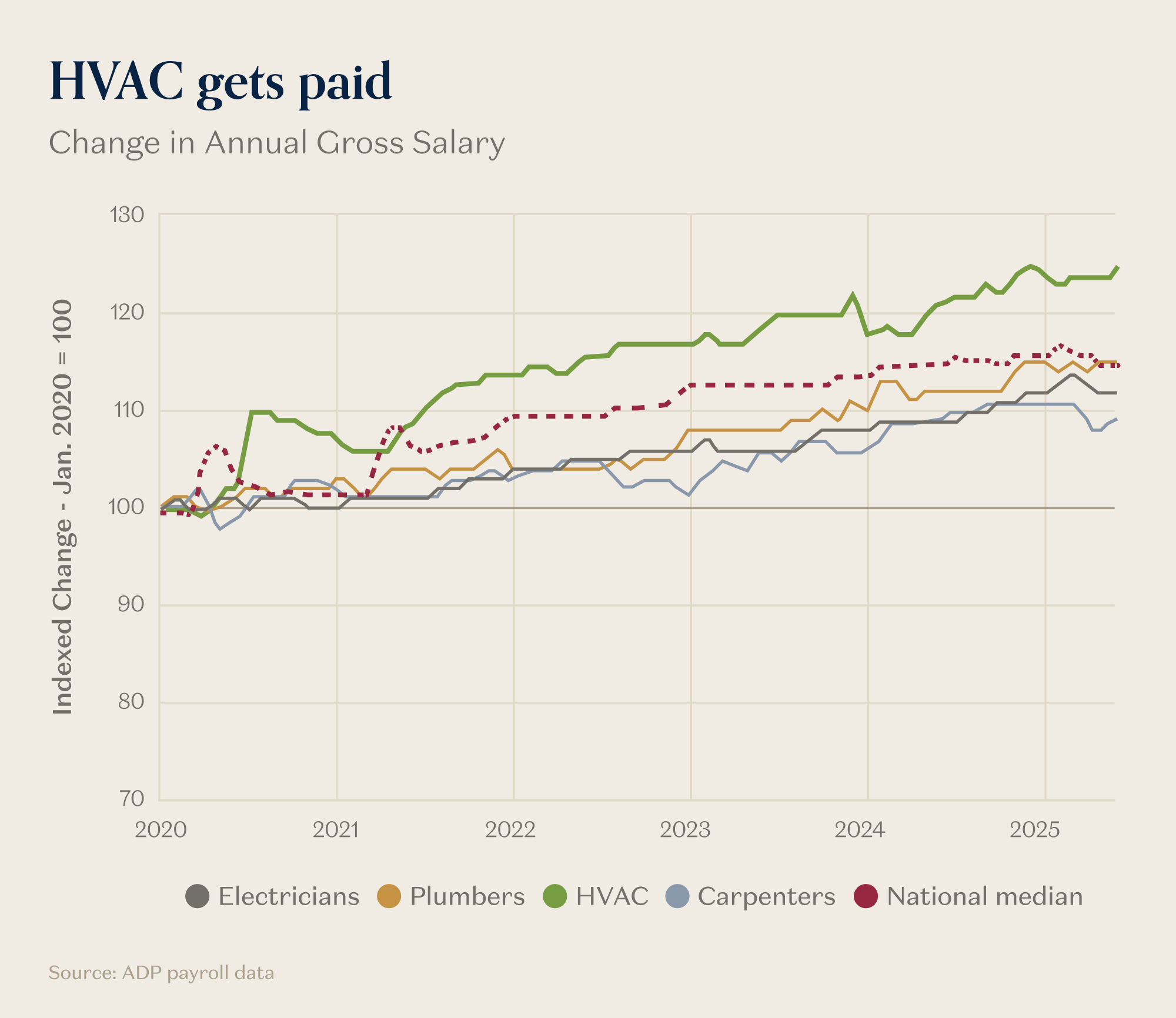

Chances are, you’ve probably seen a version of this graph at some point:

This graph can mean different things to different people: it can mean “what’s regulated versus what isn’t” to some, “where technology makes a difference” to others. And it’s top of mind these days, as persistent inflation and the AI investment supercycle both command a lot of mindshare.

To really understand it, the best place to start isn’t with the red lines. It’s with the blue lines: where are things getting cheaper, in ways that create more jobs, more opportunity, and more spending?

The original formulation of “Jevon’s Paradox”, by William Stanley Jevon in 1865, was about coal production. Jevon observed that, the cheaper and faster we got at producing coal, the more coal we ended up using – demand more than eclipsed the cost savings, and the coal market grew rapidly as it fed the Second Industrial Revolution in England and abroad.

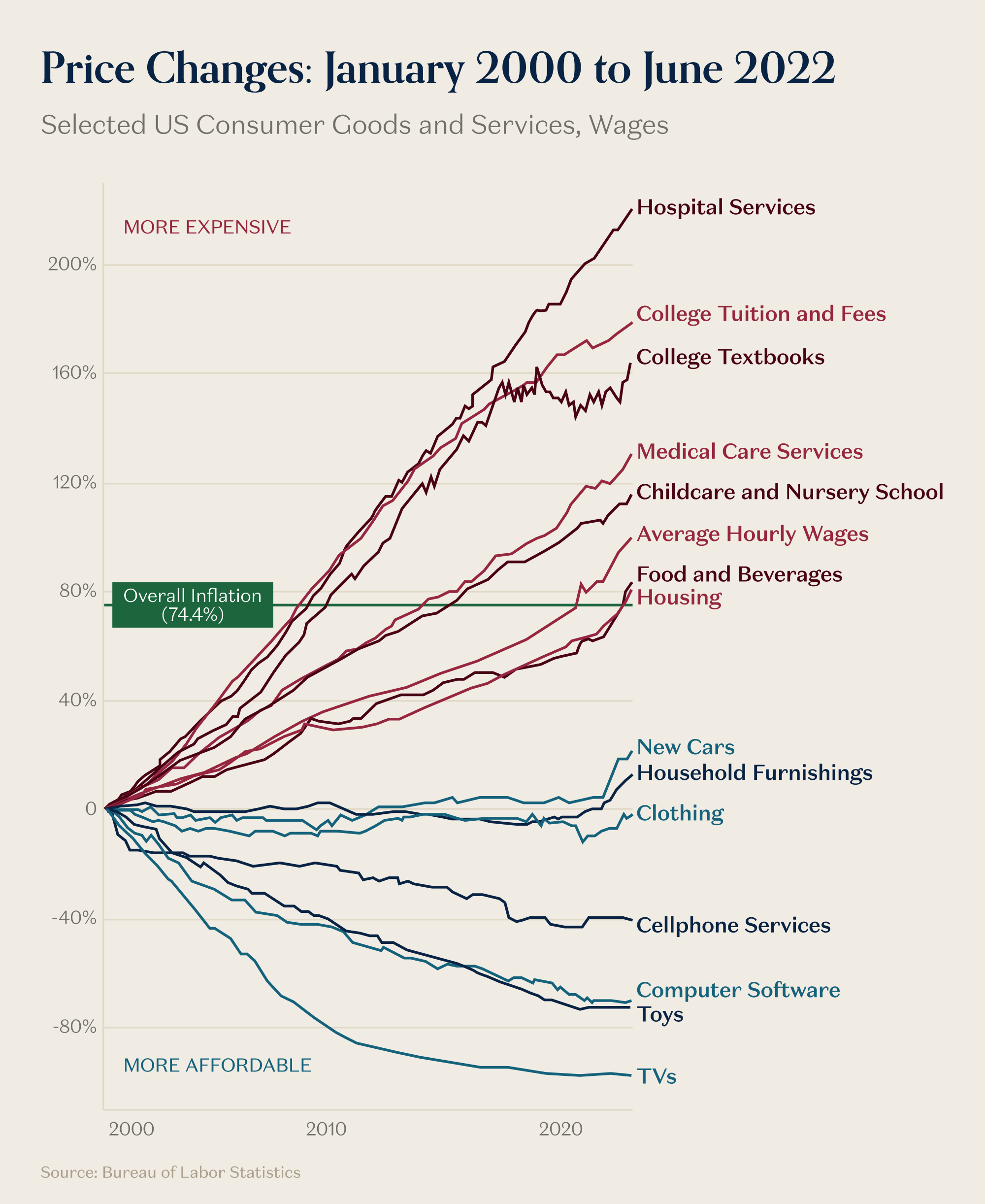

Today we all know Moore’s Law, the best contemporary example of Jevon’s paradox. In 1965, a transistor cost roughly $1. Today it costs a fraction of a millionth of a cent. This extraordinary collapse in computing costs – a billionfold improvement – did not lead to modest, proportional increases in computer use. It triggered an explosion of applications that would have been unthinkable at earlier price points. At $1 per transistor, computers made sense for military calculations and corporate payroll. At a thousandth of a cent, they made sense for word processing and databases. At a millionth of a cent, they made sense in thermostats and greeting cards. At a billionth of a cent, we embed them in disposable shipping tags that transmit their location once and are thrown away. The efficiency gains haven’t reduced our total computing consumption: they’ve made computing so cheap that we now use trillions times more of it.

We’re all betting that the same will happen with the cost of tokens, just like it happened to the cost of computing, which in turn unlocks more demand than can possibly be taken up by the existing investment. The other week, we heard from Amin Vahdat, GP and GM of AI and Infrastructure at Google Cloud, share an astonishing observation with us: that 7 year old TPUs were still seeing 100% utilization inside Google. That is one of the things you see with Jevon’s Paradox: the opportunity to do productive work explodes in possibility. We are at the point in the technology curve with AI where every day someone figures out something new to do with them, meaning users will take any chip they can get, and use it productively.

Jevon’s Paradox (which isn’t really a paradox at all; it’s just economics) is where demand creation comes from, and where new kinds of attractive jobs come from. And that huge new supply of viable, productive opportunity is our starting point to understand the other half of our economic puzzle: what happens everywhere else.

Baumol’s: how the wealth gets spread around

Agatha Christie once wrote that she never thought she’d be wealthy enough to own a car, or poor enough to not have servants. Whereas, after a century of productivity gains, the average American middle-class household can comfortably manage a new car lease every two years, but needs to split the cost of a single nanny with their neighbors.

How did this happen? 100 years after Jevons published his observation on coal, William Baumol published a short paper investigating why so many orchestras, theaters, and opera companies were running out of money. He provocatively asserted that the String Quartet had become less productive, in “real economy” terms, because the rest of the economy had become more productive, while the musicians’ job stayed exactly the same. The paper struck a nerve, and became a branded concept: “Baumol’s Cost Disease”.

This is a tricky concept to wrap your head around, and not everyone buys it. But the basic argument is, over the long run all jobs and wage scales compete in the labor market with every other job and wage scale. If one sector becomes hugely productive, and creates tons of well-paying jobs, then every other sector’s wages eventually have to rise, in order for their jobs to remain attractive for anyone.

The String Quartet is an odd choice of example, because there are so many ways to argue that music has become more productive over the past century: recorded and streaming music have brought consumption costs down to near zero, and you could argue that Taylor Swift is “higher quality” for what today’s audiences are looking for (even if you deplore the aesthetics.) But the overall effect is compelling nonetheless. As some sectors of the economy get more attractive, the comparatively less attractive ones get more expensive anyway.

Once you’ve heard of Baumol’s, it’s like you get to join a trendy club of economic thinkers who now have someone to blame for all of society’s problems. It gets to be a successful punching bag for why labor markets are weird, or why basic services cost so much – “It’s a rich country problem.”

But the odd thing about Baumol’s is how rarely it is juxtaposed with the actual driving cause of those productivity distortions, which is the massive increase in productivity, in overall wealth, and in overall consumption, that’s required for Baumol’s to kick in. In a weird way, Jevon’s is necessary for Baumol’s to happen.

For some reason, we rarely see those two phenomena juxtaposed against each other, but they’re related. For the Baumol Effect to take place as classically presented, there must be a total increase in productive output and opportunity; not just a relative increase in productivity, from the booming industry and the new jobs that it creates. But when that does happen, and we see a lot of consumption, job opportunities, and prosperity get created by the boom, you can safely bet that Baumol’s will manifest itself in faraway corners of the economy. This isn’t all bad; it’s how wealth gets spread around and how a rising tide lifts many boats. (There’s probably a joke here somewhere that Baumol’s Cost Disease is actually the most effective form of Communism ever tried, or something.)

Why it costs $100 a week to walk your dog (but you can afford it)

So, to recap:

- “Jevon’s-type effects” created bountiful new opportunity in everything that got more productive; and

- “Baumol-type effects” means that everything that didn’t get more productive got more expensive anyway, but we consume more of it all the same because society as a whole got richer.

As explained in one job: our explosion of demand for data centres means there’s infinite work for HVAC technicians. So they get paid more (even though they themselves didn’t change), which means they charge more on all jobs (even the ones that have nothing to do with AI), but we can afford to pay them (because we got richer overall, mostly from technology improvements, over the long run). Furthermore, the next generation of plumber apprentices might decide to do HVAC instead; so now plumbing is more expensive too. And so on.

Now let’s think about what’s going to happen with widespread AI adoption, if it pays off the way we all think it will. First of all, it’s going to drive a lot of productivity gains in services specifically. (There is precedent for this; e.g. the railroads made the mail a lot more productive; the internet made travel booking a lot more productive.) Some services are going to get pulled into the Jevon’s vortex, and just rapidly start getting more productive, and unlocking new use cases for those services. (The key is to look for elastic-demand services, where we plausibly could consume 10x or more of the service, along some dimension. Legal services, for example, plausibly fit this bill.)

And then there are other kinds of services that are not going to be Jevons’ed, for some reason or another, and for those services, over time, we should expect to see wildly high prices for specific services that have no real reason to AI whatsoever. Your dog walker has nothing to do with AI infrastructure; and yet, he will cost more. But you’ll pay it anyway; if you love your dog.

Reflexive Turbo-Baumol’s: why jobs will get weird

The last piece of this economic riddle, which we haven’t mentioned thus far, is that elected governments (who appoint and direct employment regulators) often believe they have a mandate to protect people’s employment and livelihoods. And the straightforward way that mandate gets applied, in the face of technological changes, is to protect human jobs by saying, “This safety function must be performed or signed off by a human.”

When this happens (which it certainly will, across who knows how many industries, we’ll see a Baumol’s type effect take hold within single jobs. Here’s Dwarkesh, on his recent interview with Andrej Karpathy: (Excerpted in full, because it’s such an interesting thought):

“With radiologists, I’m totally speculating and I have no idea what the actual workflow of a radiologist involves. But one analogy that might be applicable is when Waymos were first being rolled out, there’d be a person sitting in the front seat, and you just had to have them there to make sure that if something went really wrong, they’d be there to monitor. Even today, people are still watching to make sure things are going well. Robotaxi, which was just deployed, still has a person inside it.

Now we could be in a similar situation where if you automate 99% of a job, that last 1% the human has to do is incredibly valuable because it’s bottlenecking everything else. If it were the case with radiologists, where the person sitting in the front of Waymo has to be specially trained for years in order to provide the last 1%, their wages should go up tremendously because they’re the one thing bottlenecking wide deployment. Radiologists, I think their wages have gone up for similar reasons, if you’re the last bottleneck and you’re not fungible. A Waymo driver might be fungible with others. So you might see this thing where your wages go up until you get to 99% and then fall just like that when the last 1% is gone. And I wonder if we’re seeing similar things with radiology or salaries of call center workers or anything like that.”

Just like we have really weird economies in advanced countries (where we can afford supercomputers in our pockets, but not enough teachers for small class sizes), we could see a strange thing happen where the last 1% that must be a human in a job (the “Dog Walker” part, as opposed to the “Excel” part) becomes the essential employable skillset.

In an interesting way, this hints at where Baumol’s will finally run out of steam – because at some point, these “last 1% employable skills” no longer become substitutable for one another. They’ll become strange vestigial limbs of career paths; in a sense. We have a ways to go until we get there, but we can anticipate some very strange economic & political alliances that could get formed in such a world. Until then, let’s keep busy on the productivity part. Because that’s what matters, and what makes us a wealthy society – weird consequences and all.