The U.S. mental health system is under tremendous strain. Depression is now the leading cause of disability in the U.S. One in four Americans suffered from a diagnosable mental disorder in the last year, most of which were moderate to severe. We spend ~$200 billion dollars annually on mental health treatment — more than on any other medical condition. And yet we still have problems getting people the help they need.

The overwhelming need — and giant lag — in the system boils down to two things: coordinating care in our current health care framework, and getting the right treatment conveniently.

Sounds simple, but as obvious and innocuous as those problems sound, they aren’t being addressed, and they have significant and far-reaching consequences: Mental health affects everything from economic productivity to other chronic medical conditions. The average monthly medical cost of a person with diabetes, for example, is $811; that cost skyrockets to $1775 for a person with diabetes and a mental health condition. Estimates place the additional healthcare costs from people in the U.S. with such mental health co-morbidities at ~$300 billion.

Depression is now the leading cause of disability in the United States

What makes this problem particularly challenging is that unlike most medical specialities, where the mainstay of treatment is a provider treating a patient with a pill or procedure, in mental health treatments like psychotherapy, the interaction with a medical professional is often the treatment itself. So maintaining consistently high quality among mental health providers is especially important. Unfortunately, today’s minimal and manual outcome tracking makes that hard.

The great mental health challenge we’re facing right now isn’t just one of developing new therapies; it’s one of scalability and convenience. And that’s precisely where software can play a role in healing and protecting our mental health — for the treatment itself, as well as the overall mental health support infrastructure.

About that infrastructure problem…

“We’ll call you back in a month to set up an appointment.” You’ve probably heard this yourself too many times. We certainly did when calling a well-known mental health institution recently. (It took us two months to get an appointment with a psychiatrist. And that doctor ended up being out of network.) We aren’t alone. One recent study of 360 psychiatrists resulted in only a 26% appointment rate, and getting that first appointment took an average of 25 days.

As anyone who has had this problem knows, appointment timing (and subsequent diagnosis) matters. Due to the existing infrastructure, up to 60% of adult Americans currently go undiagnosed — and therefore never seek mental health treatment. The main infrastructure goal should be to find mental health patients early, get them appropriate care, and track and update treatment based on progress.

Why is this so hard? Some of the problems with recognition and treatment stem from the fact that we actually have two separate medical systems: one for primary care (that’s more generalized), and one for mental health care (that’s more specialized). Simply put, psychiatrists and other mental health professionalists are more highly trained in spotting mental health diseases than primary care physicians (PCPs) are. And even when PCPs identify those in need, they don’t always have appropriate referrals or providers for their patients. As a result, PCPs end up directly treating patients with mental health issues themselves — 80% of psychotropic drugs are prescribed by PCPs rather than psychiatrists.

To break the barriers between the primary care and mental health care worlds, we need to establish frequent feedback and communication. One approach for doing this is the “collaborative care” model for mental health care, developed with the American Psychiatric Association. By having a depression care manager (often a nurse) “quarterback” the patient’s mental health journey — led by a PCP but coordinating and collaborating closely with mental specialists (and communicating with patients) along the way — the collaborative care model merges the two separate worlds. Over 70 trials have shown that this approach has positive health and economic benefits.

Another example of such an approach is the “integrated care” model, which often physically co-locates a primary care and mental health specialist — like next door to each other, as in VA hospitals. So when a PCP suspects a patient may have mental health issues during a routine visit, they can immediately do a “warm hand-off” to the mental health specialist next door. This immediate assessment ensures that patients don’t fall through the cracks.

Sounds great. Unfortunately, these models are labor intensive and expensive. Enter software, which can greatly help to make the overall system cheaper and more efficient, by adopting, scaling, and automating the system coordination while retaining the human touch. Only now, that touch is more focused on true care as opposed to coordination. One example of such a company is Omada Health [disclosure: we’re investors], which took an existing, effective evidence-based program (the Diabetes Prevention Program) and digitized and scaled the treatment so it would be less labor-intensive and expensive. They did this by keeping human coaches at the core, and then automating away the less central parts of the program through an online curriculum, self-weigh-ins (over 10,000,000 user weigh-ins!), and more. Not only did this reduce costs and massively increase the coach:user ratio, more crucially, it showed comparable effectiveness and results to the original program.

We’re now seeing similar efforts to digitize collaborative care for the mental health world, led by companies like Quartet Health and Lyra Health among others. For example, software can crunch through electronic medical record and insurance claims data to automatically surface patients at risk for mental health disorders. Software tools can also help find the appropriate mental health provider; establish personalized treatment plans; open lines of communication between the PCP, patient, and mental health provider; and continuously update the patient’s course of treatment based on their progress.

The great mental health challenge we’re facing right now isn’t just one of developing new therapies; it’s one of scalability and convenience.

But what about treatment?

There are multiple forms of psychotherapy, most of which are high touch and focus on discussions between the patient and the therapist — and thus are difficult to scale. The most well-studied is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which involves highly structured behavioral exercises and therefore lends itself well to digitization by software.

Software-based approaches to CBT aren’t really new. Studies on computerized cognitive behavioral therapy (CCBT) date back to 1990, and have been distributed — via CDs! — in 200 countries, including the UK and Australia. What’s changed since then is internet + mobile, which creates the ideal conditions for delivering software-based CBT. This has led to an explosion of mental health technology companies in the past few years, from internet-based CBT to more recently, mobile CBT.

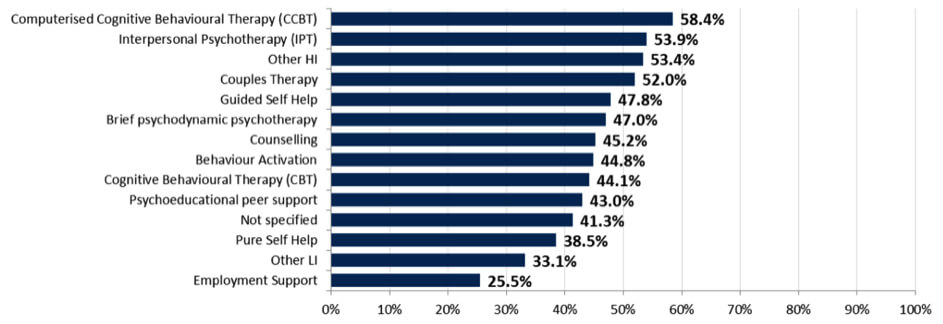

While automated approaches relative to in-person therapies have generated healthy skepticism about efficacy, studies show promising results. A review of the research literature showed that software-based CBT is quite effective in treating depression and other mental health illnesses. Even more compelling are the recent results of a nation-wide multi-year study in the UK surveying different types of psychotherapies for the treatment of depression: Computerized cognitive behavioral therapy had the highest recovery rate of 58% — beating out in-person psychotherapies and self/peer-help programs. That’s a stunning result.

recovery rates by therapy type for referrals with a problem descriptor of depression, 2014/15 [source]

There’s still plenty of room for improvement in the field of software-based CBT, though, especially given the challenge of generalizing results to real-world populations. For instance, minimal patient engagement is a common concern and complaint. One recent study investigating the use of CCBT in conjunction with general practitioner (the UK equivalent of a PCP) care claimed that the computer version did not provide any additional value beyond standard primary care — but the study also noted that their CCBT products had limited patient engagement, which interfered with the effectiveness. The products used in the trial most likely weren’t using the latest engagement and retention techniques that modern technology companies use. They didn’t even have mobile apps or mobile-optimized websites, and mobile is one of the most powerful engagement tools in a software company’s repertoire! Software-enabled companies like Joyable and Lantern Health have built CCBT products that combine sophisticated design and personalized exercises, augmented with guidance from a coach.

We believe such “digital therapeutic” models are a very effective, non-toxic way of scaling health care through software.

There are other approaches, too, from message-based platforms (Talkspace) and peer-to-peer support networks (7 Cups of Tea) to “telepsychiatry” (1DocWay) and many others. There’s no question that compared to traditional therapy, these products are far easier to scale, cheaper, and allow for consistent measurement of outcomes — and therefore can help get treatment to millions more people. And the ubiquity of the mobile phone means that treatment is only seconds away and available on demand, something consumers now expect in every other aspect of their lives. With new immersion-based platforms like VR that increase the degree of immersion in traditional treatments like exposure therapy, we expect software-augmented mental health approaches to only get more powerful and effective over time and as technologies evolve.

Where do we go from here (and why is that hard)?

Software clearly creates tremendous possibility in mental health. It’s not a silver bullet for solving everything of course, but it’s an incredibly important tool for scaling treatment, reach, and access. And when you increase the reach, access, and quality of treatment, you begin to address the problem.

We believe ‘digital therapeutic’ models are a very effective, non-toxic way of scaling health care through software.

There are now real financial incentives to build such scalable healthcare solutions. In 2010, the Mental Health Parity Act mandated that group insurance/ employer-administered plans treat mental health conditions the same as physical health conditions in terms of copays and benefits. In 2014, as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the same parity was brought to individual plans sold through health exchanges. This is one of the largest expansions of mental healthcare in decades.

And yet despite this enormous opportunity — or rather, because of it — it’s important to recognize the challenges of building a sustainable company in the current healthcare system. Direct consumer-facing business models in health care are generally tougher to pull off, since it’s hard to identify, let alone capture, customers in the healthcare market. Even if those very people use social media all day, every day, they aren’t used to taking charge of their health care or even paying for healthcare tools in a software-native manner (cloud-based, software as a service, etc.). As a result, there’s a lot of competition to acquire users when they go looking for health care solutions, which in turn drives up the customer acquisition cost (CAC). The subsequent low retention of those users doesn’t make it easy to recover that return on investment, either.

This is why many tech-centric health companies that start out consumer-focused pivot into more enterprise-facing business models. Large self-insured employers or insurance companies are more willing to pay for and offer preventative healthcare solutions to their employees and members, as a means of nipping expensive medical conditions in the bud and reducing their overall healthcare spend.

However: mental health, as a chronic condition that consumers actively think about (vs. that cold that comes about once a year), is very likely to be the exception to our observation about consumer-facing vs. enterprise-facing business models. Either way, founders need to figure out what type of company they want to be early on. A startup’s organizational structure for a consumer-facing vs. enterprise-facing business model is very different, from both a marketing and sales perspective as well as in the clinical evidence needed for the software-driven product.

Of course, there will always be a place for other treatments and pharmaceuticals in solving mental health problems. But as we’re fond of saying, in the future, it’s going to seem backwards — and maybe even toxic — that our solution to everything was just giving out pills. Software is a natural start.

Thanks also to Dr. Cameron Sepah, Assistant Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at UCSF and VP Clinical Innovation at Omada, for his insights.

editors: Sonal Chokshi (@smc90) and Hanne Tidnam (@omnivorousread)