There might be no more beloved image of the American entrepreneurial spirit than that of neighborhood kids who open a sidewalk lemonade stand on a hot summer day. With a little bit of “capital” from their parents — lemons, water, sugar, a card table, some markers and paper — hard work, and good sidewalk placement, children learn about how to start a business and earn some cash along the way.

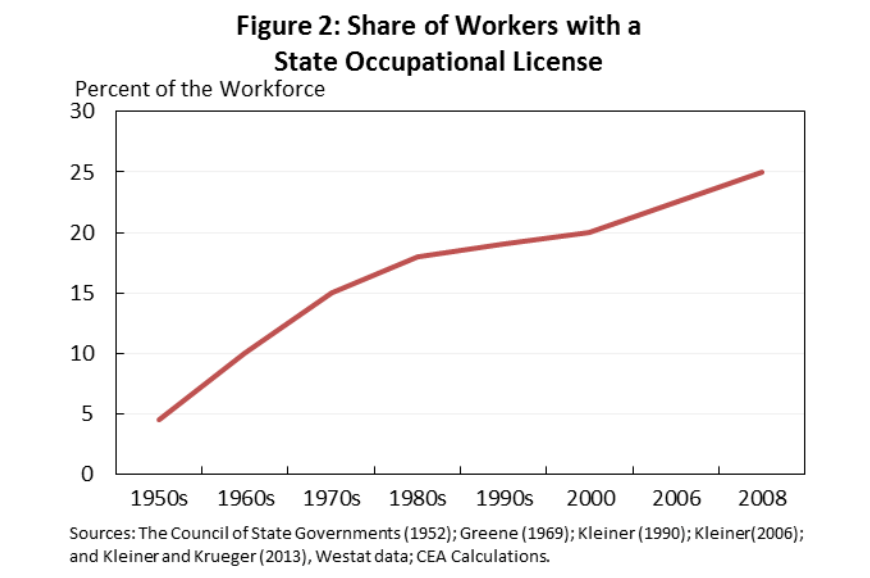

However, not only are the hurdles to actually build a grown-up version of that business today enormous, but there’s also been a massive increase in government regulation to work in or start a small business in many industries. State-mandated occupational licensing involves a combination of education, training, exams, and fees to work in certain professions, with more and more would-be entrepreneurs impacted. Whereas in the 1950s just 5% of the workforce needed an occupational license, the share has grown to more than 25% of U.S. workers today. In 2003, the Council of State Governments estimated that more than 800 occupations were licensed in at least one state. These occupations span different sectors, salary ranges, and degrees of familiarity to consumers–from upholsterers to locksmiths to milk samplers to civil engineers. A full list of licensed occupations can be found here.

The growth in state occupational licenses (source).

But this growth in licensing also presents an opportunity for marketplace startups. As the low-hanging fruit of other services marketplaces get picked off, the more challenging regulated industries are the ones that remain. The artificial supply-constraint imposed by licensing and regulation makes these services verticals particularly interesting in the context of marketplace-building. Supply-constrained markets hold advantages because there’s already a large pool of demand that wants a particular service; if such marketplaces are able to win the supply side, they can capture a ton of value.

But marketplaces are nuanced and challenging businesses to scale, and for startups operating in regulated industries, there is additional complexity and difficulty. So what can founders and operators do when it comes to navigating the complexities that come with the territory in regulated industries? Where are the opportunities?

Why managed marketplaces matter

In a previous blog post co-authored with Andrew Chen, What’s Next for Marketplace Startups, we detailed how the licensing of workers was more critical in a “pre-internet” world, since licenses established consumer trust by signaling the skills or knowledge required to perform a job. But today, digital platforms can mitigate the need for (some) licensing by establishing trust and ensuring quality through other means — such as user reviews, platform requirements, and other mechanisms like pre-vetting and guarantees.

“Managed marketplaces” models in particular can be helpful in establishing user trust, because they intermediate parts of the service delivery, adding value by taking on functions like identifying high-quality providers, standardizing prices, and automating matching between demand and supply. As scrutiny around safety for marketplaces continues to rise, the importance of trusted labor becomes even more significant. In childcare, for instance, people don’t want to just see a list of all possible caregivers — they want to know with certainty that the providers they’re hiring are trustworthy and qualified, and a managed marketplace can capitalize on this user need by thoroughly vetting all supply.

Managed marketplaces can greatly mitigate the need for licensing because users trust the marketplace itself, particularly on the highly managed side of the spectrum. Such platforms can enable high-quality, but unlicensed, suppliers to offer services alongside licensed providers — and in doing so, promote entrepreneurship and alleviate supply constraints.

Not all service categories are created equal, however, and some are more suited to digital marketplaces than others. Depending on the particular dynamics of each industry, marketplace startups will have different entry points and strategies.

Regulated services marketplaces: factors to consider

Besides all of the traditional lenses through which we evaluate all marketplace businesses, there’s some specific factors unique to categories that involve regulation that can help inform the best approach. And the sooner that founders and operators can think through and address these factors, the better for their company building.

Useful factors to consider when assessing opportunities for new marketplaces operating in a regulated industry include: (1) downside risk of unlicensed supply, (2) burden of licensing requirements, (3) existing industry satisfaction, (4) opportunity to lower prices, (5) market size, (6) latent demand, (7) underutilized assets to unlock supply, and (8) tailwinds around regulatory reform.

Of course, the framework outlined below is just a beginning point in evaluating opportunities for regulated services marketplaces. In addition to the opportunities arising from state occupational licensing, there’s also other forms of regulation — including other means of restricting businesses such as permitting and zoning — at the local (county or city) and federal level.

#1 Downside risk of unlicensed supply and consumer perception

For some occupations, licensing is critical because there is a credible, acute threat to public health and safety. Few consumers would feel comfortable having surgery performed by an unlicensed doctor, even if they had great reviews. In these cases, it makes more sense to have a marketplace that makes discovery and accessibility of licensed providers easier — rather than expanding the marketplace with unlicensed providers.

But for other services, licensing burdens can outweigh potential risks, especially in fields where the potential for adverse impact on health and safety is minimal — like tour guides, florists, or interior designers, for example.

In other words, the tangible benefits of licensing and consumer attitudes are important to consider in designing the right marketplace approach. Of course, consumer perceptions are not fixed: it was inconceivable to many that users would want to sleep in strangers’ homes or get into strangers’ cars — yet the companies that made this possible (and established trust through other mechanisms besides licensing) are now massively valuable.

For categories where consumers are cognizant of risks to unlicensed supply, a more managed marketplace approach can make sense to establish greater trust.

For instance, Outschool is an online platform offering real-time group classes for kids ages 18 and below. Teachers can apply to teach a class on the platform, but don’t need to possess a teaching license, unlike teachers in charter and public schools. But parents are sensitive to potential safety issues when it comes to children’s interactions with adults online, so Outschool closely manages the marketplace. Teachers must go through background checks and an application process; once approved, teachers must then submit class listings for approval within Outschool’s content policy. As a result, consumers are assured of quality, while the marketplace is able to scale on the teacher side.

There is no one-size-fits-all approach for establishing new marketplace startups in regulated industries: the benefits of licensing, the degree of risk associated with unlicensed service providers, and how important customers perceive the licensing to be are critical considerations.

#2 Licensing requirements: How challenging is it to become licensed, and can a marketplace expand supply?

Each state and profession has different licensing requirements, in terms of training, testing, education, and fees. The more burdensome the licensing requirements, the higher the barriers for professionals aspiring to enter that industry — which means a greater potential opportunity for marketplace companies seeking to enable more supply to enter the industry.

In industries where licensing requirements are particularly burdensome to would-be professionals, some marketplaces are facilitating or creating more supply by, for instance, providing education, training, and support in getting licensed. Marketplaces startups that would otherwise find themselves constrained by lack of supply can grow more quickly by establishing their own proprietary source of supply.

For instance, Nana is a marketplace focused on appliance repair and smart home installation — but also has an online academy that trains workers to become appliance technicians. Because of the supply-constrained dynamics in the industry, the company created the Nana Academy in order to create more supply.

Similarly, Lacquerbar is a chain of nail salons that also operates an online education platform for manicurists, inspired by the founder’s own experience in beauty school, where she realized that the standard curriculums often don’t include modern nail techniques and business skills needed for launching careers.

In the education space, Wonderschool helps educators and childcare providers go above and beyond the licensing requirements necessary to launch and operate their own in-home childcare programs. Wonderschool’s mentoring program also helps providers choose a curriculum, set up their home learning environments, and determine their operating playbook for parents, based on best practices.

For founders operating companies in severely supply-constrained verticals, approaches like these — combining education, training, and guidance for the supply side — can be valuable in enabling more supply to enter the industry and thereby growing the marketplace.

#3 Existing industry satisfaction and Net Promoter Score

Industries that entail licensing/regulation and have low NPS are good targets for disruption, because consumers are dissatisfied with the status quo. Companies that are able to offer a step-function improvement in customer experience can win the favor of a large user base — and potentially create their own path to regulatory change.

Case in point: Uber’s NPS is 37, whereas traditional taxi companies had negative NPS scores — anyone who recalls the experience of calling a taxi company and booking a car in advance can understand the delta here. This improved customer experience in terms of reliability and price helped Uber to garner widespread user support which pressured regulators to allow the service to operate.

In the home insurance world, Hippo uses a tech-driven approach to offer cheaper policies and a simpler process to homeowners, in a manner that complies with regulation. The company has been able to achieve an NPS of 76 — whereas legacy carriers have an average NPS of 31 — based on a differentiated experience across the customer lifecycle, from faster onboarding to continuous underwriting to a claims concierge team.

Honing in on industries with low NPS and aiming to create a dramatically better user experience to widen the NPS gap is a common theme among successful services marketplaces.

#4 Opportunity to lower prices

If existing services have artificially high prices due to restricted supply, then startups can offer a compelling value proposition and expand the market by competing on price. There is greater opportunity to lower prices more dramatically when the approach to the supply-side is inherently different from the pre-existing licensed supply model, for instance by introducing an unlicensed version of supply.

For instance, many startups are aiming to democratize access to mental health treatment by broadening who is able to provide such services. Traditionally, therapy is an expensive, luxury product — and among all practicing medical professionals, therapists are the least likely to take insurance (source). By utilizing trained but unlicensed providers, startups like Sibly and Marlow, which provide coaching services through a mix of text, voice, and video, are able to significantly reduce prices and expand the addressable market size. Although these solutions don’t and shouldn’t entirely replace therapy, especially among patients with more severe cases, they can be a useful, accessible solution and widen the market for new customers.

#5 Market size: How large is the industry today?

As with any marketplace, the size of the market matters. For regulated industries, it’s important to consider how many licensed providers exist and how many states require licensing in the profession. The larger the existing market, the greater the addressable audience of customers who could benefit from a marketplace which improves matching between supply and demand and enhances transparency and accessibility of the service.

For example: in the past few years, there’s been an explosion of trucking startups, including Convoy, NEXT Trucking, and Uber Freight — marketplaces that connect shippers (like CPG companies or retailers) with carriers (the trucking companies providing transportation of goods). The reason is simple: it’s a massive industry. According to the American Trucking Associations, in 2017 the trucking industry employed over 3.5M drivers in generating over $700Bn revenue — as a comparison, the global ridesharing market was worth $60Bn in 2018. Furthermore, truck drivers are licensed in all 50 states. The massive market size — combined with a number of other factors including manual existing processes, inefficient capacity utilization, and high fragmentation on the demand and supply sides — means a big opportunity to create efficiencies along the value chain.

#6 Latent demand: How large could the industry be?

Another important aspect to consider along with current market size is latent demand, i.e. the potential size of the market.

In the early days of ridesharing and home rentals, many investors underestimated the market sizes of Airbnb, Lyft, and Uber, because the existing markets were relatively small, and ostensibly already well-served, for taxis and travel accommodations. Uber’s first pitch deck from 2008 cited research that the taxi and limousine market would grow at just a 2% CAGR, and that their “best-case scenario” was reaching $1B+ in yearly revenue. But it turned out that many people wanted the service if the price decreased and it became more convenient — in other words, there was a lot of latent demand — and the market size ended up being a lot larger than predicted.

Given licensed occupations are by definition supply-constrained, current measures of market size don’t always fully capture how large the industry could be if restrictions were relaxed.

Measuring latent demand is tricky, however. It can be proxied by surveying users or by running a test of the service, to understand consumer elasticity of demand.

#7 Availability of underutilized assets to unlock supply

Another aspect that’s compelling for potential marketplaces is the availability of underutilized assets that can supplement and differentiate the supply-side. In Airbnb’s case, enabling regular homeowners to rent out spare rooms greatly expanded the pool of available vacation rentals. Having an underutilized asset that can unlock the supply side of the marketplace means greater access and lower prices.

Some potential examples of underutilized assets in marketplaces include:

- Private land: Hipcamp is building a marketplace for camping that enables users to book private land vs. many national and state parks that require permits for camping. This kind of inventory differentiates the marketplace from a consumer perspective, and is also attractive to landowners as a way to monetize their land.

- Private parking lots: AirGarage, a managed marketplace for parking, makes the parking spaces owned by churches, small businesses, and schools available for booking by consumers. This unlock of an underutilized asset enables lower prices and convenience to consumers and incremental earnings to businesses and other organizations.

#8 Tailwinds around regulatory reform

Momentum for licensing reform creates openings for startups to enter the market, aided by changing regulation. Perhaps the biggest recent example of how regulatory tailwinds can enable more startups is around marijuana: 11 states and DC have now legalized small amounts of marijuana for adult recreational use. As a result of the ensuing expansion of the addressable market, a record amount of venture capital is pouring into the space.

Tracking changes in the regulatory environment can help identify new opportunities. Between 2012-2017, the average state actually increased the breadth and burden of licensure by 4%, but 10 states made reductions to their licensing practices (source).

Some examples where there’s activity happening include:

- Within hair and beauty, states like Arizona stopped requiring eyebrow threaders to have an occupational license in 2011 and exempted makeup artists from needing a cosmetology license in 2015, which greatly opened the potential labor supply. Perhaps more significantly, this April, Arizona became the first state to recognize and accept all out-of-state licenses, eliminating the need for people relocating from other states to endure the process of getting re-licensed. What all of these changes mean is that providers can more easily offer their services in Arizona–potentially leading to openings for startups helping consumers navigate and transact in these categories.

- In September 2018, California passed a law allowing cottage food makers to apply for a license to sell homemade foods up to $50K annually. The new law requires counties and cities to choose whether or not they want to conduct inspections and issue permits (source). So far, only Riverside County has started accepting applications for home-based food business permits. We’ll be watching this industry closely to track developments.

Where the opportunities are

We find all of the below opportunities in regulated industries to be especially interesting. Obviously, this list is not exhaustive, but these are verticals where we are particularly interested to see innovation:

Cottage foods

We are passionate about online platforms that empower people to make a living from their passions and unique skills, and cooking definitely comes to mind as an example. Cottage foods are regulated differently depending on state, and there are tailwinds for reform in some markets.

With the rise in consumers preferences shifting towards delivery and takeout, we’re excited about startups that are enabling home chefs and cottage food producers to find customers for their creations. Home kitchens are unused most of the day, and there’s an opportunity to match hungry consumers with home cooks looking to earn extra money. And unlike restaurants, which are limited by real estate space and need permits to set up and operate, home cooking platforms can offer more food variety at competitive prices.

Telemedicine and blended service delivery

Given that healthcare practitioners are the industry with the highest percentage of workers with a professional license, we’re excited about platforms that are making it easier for patients to access licensed providers when it’s convenient for them.

New telemedicine startups like Fuzzy for veterinary care are making care more accessible, cheaper, and higher-quality, by making it possible for patients/clients and doctors to communicate remotely and asynchronously.

Home services & skilled trades

A number of skilled, consumer-facing trades — like plumbing, electricians, and landscaping contractors — have licensing requirements at the state and/or local level.

Furthermore, many of these service verticals are experiencing worker shortages due to a number of factors, ranging from social stigma against trade schools, to increasing emphasis on college degrees and white collar work as the surer pathway to success. According to the National Electrical Contractors Association, 7,000 electricians join the field each year, but 10,000 retire (source). Baby Boomers hold a majority of many skilled trade jobs — and as they retire, millions of roles will be left vacant.

Just as there’s been a number of education and career placement startups that are addressing worker shortages in the tech industry — like Lambda School, Make School, and SV Academy — we think there’s also room for a “Come for the education, stay for the network” play in skilled trades. There’s an opportunity for marketplaces in these supply-constrained service verticals to go beyond simple aggregation of existing providers, into training and education of workers new to the industry.

Cosmetology

All 50 states and DC require a license to work as a cosmetologist, a profession that encompasses providing beauty services like shampooing, cutting, coloring and styling hair, applying makeup, and skin and nail services. On average, these laws cost aspiring cosmetologists $177 in fees and over a year (386 days) in education and experience and require them to pass two exams (source).

The second order effect of this is that for most consumers, getting one’s hair done or makeup professionally applied is a splurge reserved for special occasions. We’re interested in ways to fundamentally change the supply model such that these services become accessible for anyone, anytime, particularly in cases where applications of artificial intelligence and computer vision can enable this accessibility.

We would love to talk to any founder building marketplaces here!

-

Li Jin