Primary care was meant to be the front door to the healthcare system: the one-stop-shop we rely on for all of our general healthcare needs, and to help us navigate the rest of the convoluted care delivery ecosystem.

But as a front door, it’s pretty broken.

The impact of COVID-19 has shown us this more than ever before—primary care’s already overburdened system has crumbled under the pressure, with patients left to self-diagnose without lab tests or in-person visits, wait in eternal telephone queues for callbacks that may or may not happen. In short, the very place in the healthcare system that was supposed to help catch illness soonest, in fact, created barriers.

The truth is, though, it may have never been set up for success in the first place, given its extremely broad mandate.

The truth is, primary care may have never been set up for success in the first place, given its extremely broad mandate.Just consider the number of billing codes primary care has to manage: more than five times the number of billing codes (the mix of services that can be billed for and reimbursed through insurance) than the next specialty. Despite the fact that primary care physicians (PCPs) are the ones handling the vast majority of visit volume (52% of ~1B annual outpatient visits), primary care has been both underappreciated and under-compensated—only 5%-8% of overall healthcare spend (PDF), and the lowest annual income amongst all specialties (PDF).

But the value of primary care is increasingly being recognized. Higher utilization of primary care has frequently been shown to result in better health outcomes and lower costs. And the core purpose of the push towards value-based care is to reward maintenance of health through regular engagement of patients before they get very sick—i.e., the very definition of “primary” care.

Primary care’s quest to serve any patient who walks into a clinic—whether a young adult with mental health issues, a chronically ill senior with multiple comorbidities, or a new mom—paradoxically makes it ill-prepared to provide anything close to best-in-class care to each individual patient.

So how does primary care need to evolve to deliver on its potential?

Like any broad platform that provides services across different sectors, eventually, there comes a point where tailoring products and services to specific segments of the population will better serve their unique needs.

In other words, primary care needs to be unbundled.

Like any broad platform... eventually, there comes a point where tailoring products and services to specific segments of the population will better serve their unique needs. In other words, primary care needs to be unbundled.The unbundling of primary care

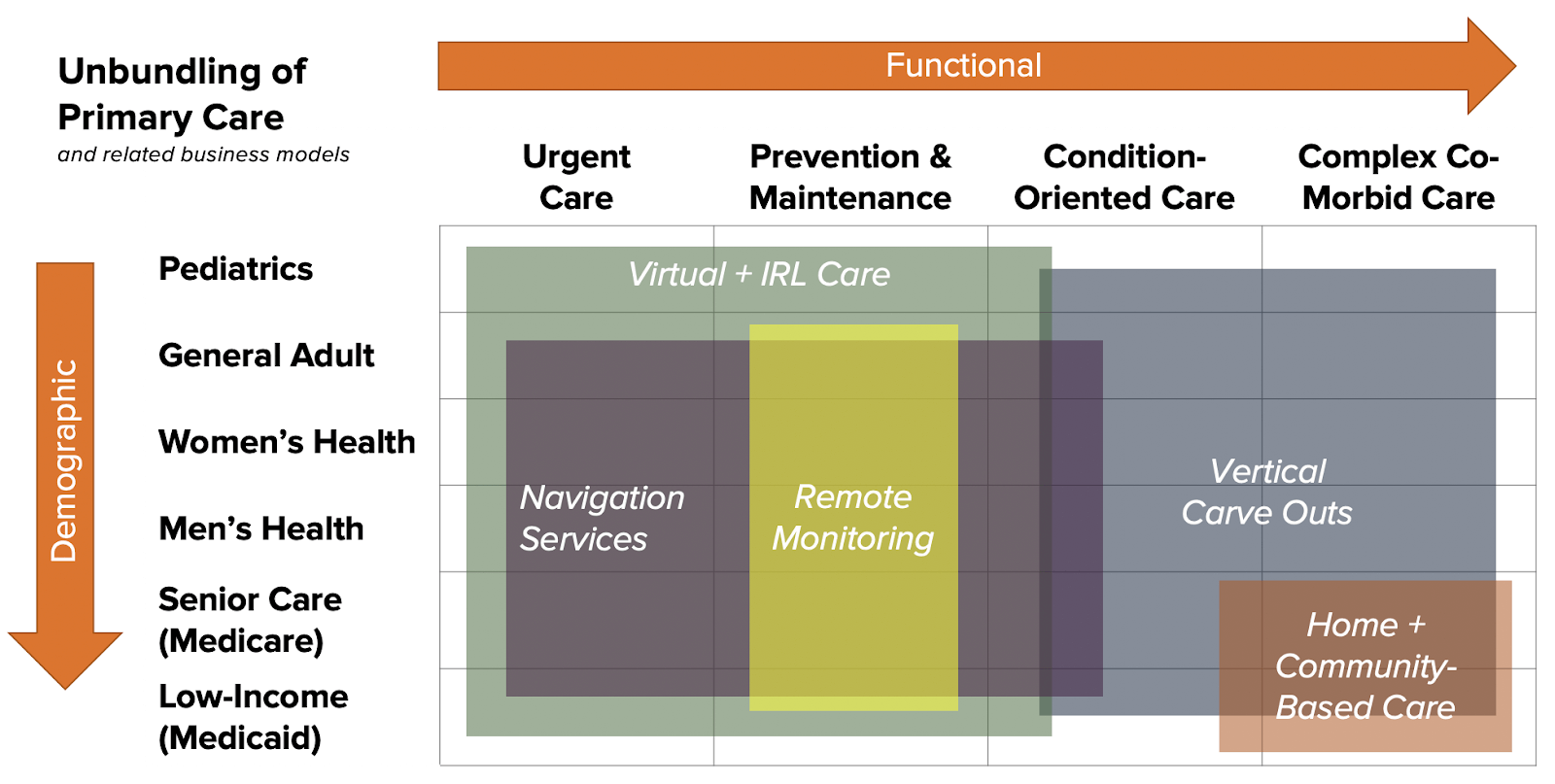

“Unbundling” the broad platform of primary care—i.e., segmenting the universe of customers (patients), so that care becomes more verticalized and personalized—can take several different approaches.

One is to change up the service mix. Providers or clinics can optimize for access and convenience around a limited scope of PCP services, as evidenced by the rapid emergence of retail clinics, urgent care clinics and virtual care providers over the last several years. People who self-select to these services tend to be young and healthy, and are willing to pay out-of-pocket for better access and convenience. These new “alternative sites of care” have been a major release valve for the pent up demand for primary care in the system.

Another approach is to serve specific patient populations with higher-end needs, who drive the majority of spend today, e.g., the elderly and frail, the low-income and chronically ill—and take advantage of established reimbursement streams for those populations.

There has already been a proliferation of startups building focused care models for Medicare and Medicaid populations, with a mix of clinic-based, home-based, and virtual services, supported by government payment programs.

And then there’s the middle, or most of the rest of us: patients going through specific health journeys related to their demographics. We’re seeing startups emerge to focus on young children, Asian-focused care (heart health, etc.), LGBTQ populations, and more.

One particularly important demographic, for example, is reproductive-age women. Their healthcare needs are very distinct, making it a population conducive to focused care models. And because mothers tend to drive the majority of healthcare decisions for themselves and their families, they can represent a high lifetime value to providers over time if clinics get their loyalty.

A new operating system for primary care

These new care models come with requirements that existing technology systems are simply not designed to serve.

Traditional EHRs are great storage systems for transactional, encounter-based data (visit by visit, service by service), but have little notion of a patient’s care journey over time, and no relevant benchmarks for comparing how this patient is doing relative to others with shared characteristics.

These new care models come with requirements that existing technology systems are simply not designed to serve.We’re also getting to a tipping point where the utility of data sitting in traditional EHRs (electronic health records including clinic medical records) may soon be outweighed by the value of data coming from other sources—such as remote-monitoring devices, care managers, digital care providers, patient-reported data, lab results, and even non-clinical sources.

Finally, as novel payment models arise outside of the revenue machine of traditional healthcare, such as direct primary care, atomic insurance, and bundled payments, there will be a need for consumer-friendly fintech products that create transparent, efficient and delightful (not scary and confusing) billing and payment experiences.

Just as the personalized medicine movement led us to more effective treatments for discrete patient populations, the unbundling of primary care will allow us to provide better care, managed more cost-effectively, for more targeted segments of the population.

To do that, we will need tech infrastructure that actually delivers on the promise of a connected care delivery system that is patient-centric, and that uses data to intelligently personalize care and automate the rote administrative tasks that hold providers back from doing their best work.

Primary care needs a new operating system. One that captures data about patients through engagement—reaching far beyond the in-person clinical encounter. One that automates efficient financial transactions based on that data. One that intelligently routes care to the right place the first time, instead of relying on consumers to do their own research or doctors to rely on printed referral directories.

One that actually considers the patient as a primary end-user and provides ready access to care on patients’ terms.

This article first appeared in FierceHealthcare.