This first appeared in the monthly a16z fintech newsletter. Subscribe to stay on top of the latest fintech news.

IN THIS EDITION

- Fintech tackles the government’s distribution problem

- 23 fintech companies aiding in coronavirus relief

- Scaling a seldom-deployed fiscal tool: direct cash transfers

- The complex calculus of pandemic insurance

- Coronavirus spurs an uptick on finance apps

Want more a16z?

Sign up to get our best articles, latest podcasts, and news on our investments emailed to you.

Thanks for signing up.

Fintech can solve the government's distribution problem

Anish AcharyaWhen it comes to connecting 10 million small businesses to the largest stimulus package in history, the government has a distribution problem. Historically, institutions like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac shaped private industry and consumer behavior by distributing incentives and guarantees through banks. Today, the government is becoming increasingly reliant on the help of fintech to enable the discovery and distribution of aid and benefits. Just last week, companies including Paypal, Square, and Intuit were tapped to assist the government with its coronavirus relief program.

Currently, a disparate patchwork of more than 80 programs operates to keep 50 million Americans out of poverty. Even during the best of times, ensuring access to those programs is a problem. That challenge has been magnified by the current crisis. More than 22 million people filed for unemployment in the past four weeks; unemployment offices are swamped, and millions are still attempting to apply.

Sign up to get our best articles, latest podcasts, and news on our investments emailed to you.Want more a16z?

Thanks for signing up.

As consumers and businesses continue to adopt fintech products, governments will inevitably partner more closely with these companies to drive discovery, distribution, and engagement.

As the pandemic wears on, fintech provides assistance

Seema AmbleThis week, fintech startup Propel and nonprofit GiveDirectly announced their role in carrying out Project 100, an initiative to send $1,000 cash transfers directly to 100,000 COVID-impacted American families within the next 100 days. The $100 million project is notable for its scale, but the use of fintech to implement such relief measures is becoming increasingly common. In fact, many fintech companies are stepping up to help consumers and small businesses during the coronavirus. That effort includes disbursing stimulus checks, distributing Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans to small businesses, providing access to unemployment benefits, and offering data and infrastructure assistance.

The list of fintech initiatives has been growing by the day; we’ll update this post accordingly.

- Investing in Lio Seema Amble, James da Costa, Eric Zhou, and Brian Roberts

- Need for Speed in AI Sales: AI Doesn’t Just Change What You Sell. It Also Changes How You Sell It. Seema Amble and James da Costa

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable Seema Amble, Joe Schmidt, and Brian Roberts

- The AI Application Spending Report: Where Startup Dollars Really Go Olivia Moore, Marc Andrusko, and Seema Amble

- The Rise of Computer Use and Agentic Coworkers Eric Zhou, Yoko Li, Seema Amble, and Jennifer Li

Scaling a seldom-deployed fiscal tool: direct cash transfers

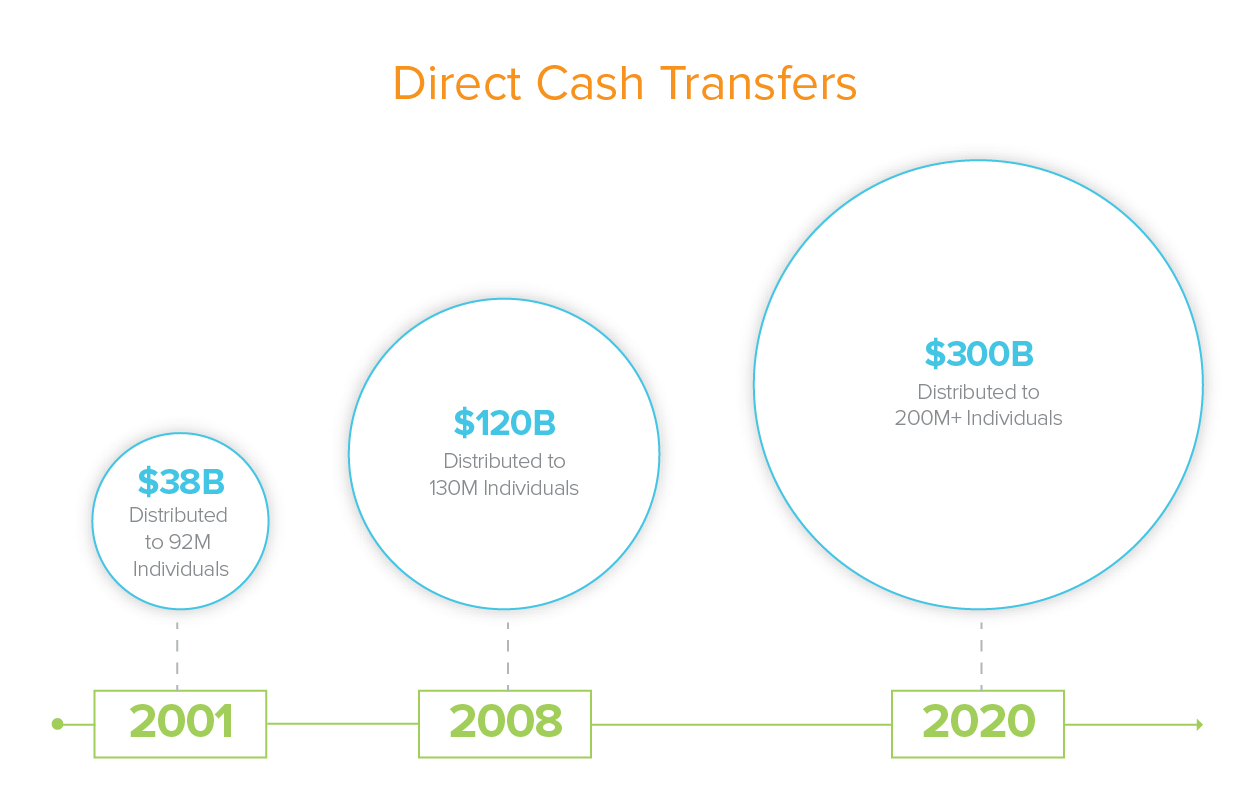

One of the enduring impacts of Covid-19 will be the expanded use of a fiscal tool to combat economic calamity: direct cash transfers. This month, millions of Americans started receiving checks directly from the US government, $1,200 per adult and $500 per child for those earning less than $75,000 ($150,000 for a household). This monumental effort accounts for the approximately $300 billion of the $2 trillion+ stimulus package.

Though this is not the first time the government has mailed stimulus checks directly to individuals, this program is unique in its size, scope, and speed. More money is being sent—quickly—to a broader segment than ever before.  Sources: 2001, 2008 & 2020

Sources: 2001, 2008 & 2020

In terms of speed and scale, no other form of intervention materially compares to directly sending money to individuals. It’s possible because the rails to deliver the $300 billion stimulus are mostly already built; the IRS already has the names, addresses, and bank account information for most Americans. It’s also incredibly flexible. Since no two households have the exact same needs—whether food, rent, or medicine—cash is far more adaptable than more targeted interventions.

Of course, direct cash transfers are no panacea. In the past, cash transfers have generated surprising little economic activity relative to the amount disbursed. In 2008, a survey found that only 20 percent of recipients increased their spending, while 30 percent increased their savings and 50 percent paid down their debt. In addition, the disbursement rails, while mostly built, are not perfect. Where there are gaps or opportunities for improvements, fintech companies are now stepping in:

- In partnership with the IRS, TurboTax is offering a free tool to enable those who don’t file taxes to still receive stimulus payments.

- Cash App and Venmo have added routing and account numbers to allow stimulus recipients, some of whom may otherwise be unbanked, to collect their checks digitally.

- Chime has piloted a feature to advance $1,200 to $100,000 to customers—before they receive the actual check from the government. For households with little to no savings, getting that money a week or two early can be hugely impactful.

- Propel is teaming up with GiveDirectly to send $1,000 cash transfers to 100,000 COVID-impacted families in the next 100 days.

Direct cash transfers have also caught on more broadly, inspiring private relief efforts. Google, for example, has also partnered with GiveDirectly to send $5 million directly to households impacted by coronavirus. If these efforts prove successful and popular, one of the lasting effects of the coronavirus may be more widespread adoption of direct cash transfers, both public and private. Where there are opportunities to create a more streamlined and intuitive experience for recipients, fintech companies can help direct money where it’s needed most.

The complex calculus of pandemic insurance

Seema AmbleAs many businesses grind to a halt, the question of insurance coverage has entered public debate. Earlier this month, President Trump suggested that unless the policy excludes pandemics, insurers should pay, and lawmakers in a handful of states have put forward legislation to force insurers to do so. Insurers, on the other hand, have pushed back. What does insurance coverage for coronavirus look like and why is it so controversial?

Business interruption insurance typically covers lost income or damage caused by a “covered peril” like theft, water damage, or fires. After the SARS outbreak in the early 2000s, most insurance companies inserted exclusions for losses caused by virus or bacteria. As a result, the typical business interruption policy does not cover lost income due to government-forced shutdown from coronavirus. Moreover, not all businesses have business interruption insurance; it’s often an optional add-on. Lloyd’s of London has an “all risk” policy that doesn’t include a virus carveout, but even then the question of whether a government mandated shutdown qualifies a physical loss is currently being litigated in court.

For insurance companies, the frequency and severity of pandemic risk is not well understood—there isn’t a widely accepted risk model. One analogy might be cyber risk, which insurance companies developed models for over time based on limited data. But while cyber risk may become easier to comprehend with each new attack, pandemics occur much less frequently.

Pandemic risk is also inherently expensive. Insurance works by risk pooling: spreading the risk across a broader group. Given the global nature of a pandemic like coronavirus, the insurer’s risk is concentrated. Unlike, say, a localized weather event, most policyholders suffer simultaneously. Similarly, since it’s unclear when business will resume in a pandemic, the severity of the risk is unknown. By definition, it’s difficult to diversify that risk.

As a result, such insurance is typically expensive, offered only to large buyers with low coverage limits. Wimbledon, for example, will receive a $141 million payout from its insurer as a result of the coronavirus-triggered cancelation. (For that, Wimbledon paid $34 million over 17 years.) In 2018, the insurance broker Marsh introduced PathogenRx—developed by the reinsurer MunichRe and epidemic risk modeler Metabiota—intended to cover mainstream businesses against pandemics. But few actually purchased PathogenRx because it was too expensive.

After witnessing the crushing impact of the coronavirus now, demand for pandemic insurance will likely drive the development of the market. Still, the question remains: at what price?

- Investing in Lio Seema Amble, James da Costa, Eric Zhou, and Brian Roberts

- Need for Speed in AI Sales: AI Doesn’t Just Change What You Sell. It Also Changes How You Sell It. Seema Amble and James da Costa

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable Seema Amble, Joe Schmidt, and Brian Roberts

- The AI Application Spending Report: Where Startup Dollars Really Go Olivia Moore, Marc Andrusko, and Seema Amble

- The Rise of Computer Use and Agentic Coworkers Eric Zhou, Yoko Li, Seema Amble, and Jennifer Li

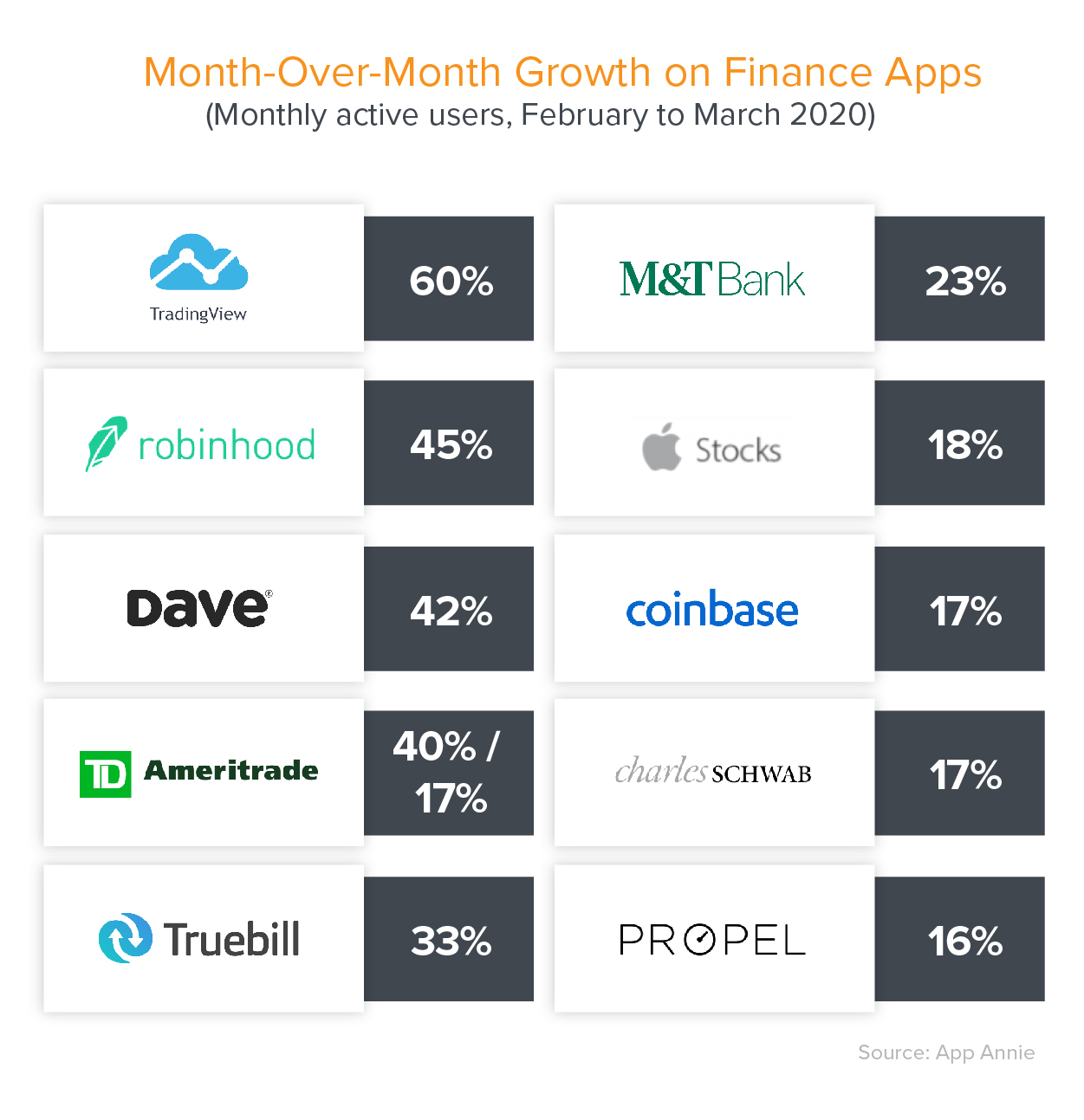

Coronavirus spurs an uptick on finance apps

As the coronavirus has spread, so has the adoption of digital banking and mobile finance apps in the US. As of last month, there were 79 finance apps among the top 1,000 apps in the App Store. On average, monthly active users for those apps rose 4 percent from February to March, according to App Annie, and total minutes spent in finance apps increased by 22 percent. That figure is slightly higher than the increase in overall usage among the top 1,000 apps last month, as many Americans shelter in place.

The finance apps that saw the biggest boost in engagement last month were brokerages, trading platforms, and stock apps—RobinHood and TradingView foremost among them—fueled by the wild volatility of the stock market. (The CBOE Volatility Index hit an all time high.) Beyond mobile-first brokerages, apps for traditional brokers such as Schwab and TD saw double-digit growth in monthly active users last month.  As the pandemic continues, it’s likely we’ll see increased usage not only of stock apps, but finance apps enabling social services and relief measures: FreshEBT and TrueBill, for example, both saw strong MAU growth in March. As millions of Americans file for unemployment and seek government assistance—and encounter crashing websites and perpetually busy phone lines in the process—fintech can help stem the tide.

As the pandemic continues, it’s likely we’ll see increased usage not only of stock apps, but finance apps enabling social services and relief measures: FreshEBT and TrueBill, for example, both saw strong MAU growth in March. As millions of Americans file for unemployment and seek government assistance—and encounter crashing websites and perpetually busy phone lines in the process—fintech can help stem the tide.

More from the a16z fintech team

The CFO in Crisis Mode: Modern Times Call for New Tools

Many businesses are reassessing their 2020 projections as world events unfold. Yet despite an influx of data on which to base decisions, the tools at the CFO’s disposal have not kept pace.

By Seema Amble and Angela Strange

Small Businesses Depend on the Stimulus Package. The Stimulus Will Depend on Fintech.

The government is unprepared to identify, adjudicate, and disburse $350 billion of aid to small businesses without a sea of fraud. Tech is the answer.

By Alex Rampell

Fintech Gets Put to the Test

On plummeting mortgage rates, policies for small business relief, and more.

By the a16z fintech team

It’s Time to Build

Every Western institution was unprepared for the coronavirus pandemic. Part of the problem is clearly foresight. But the other part of the problem is our widespread inability to build.

By Marc Andreessen

Sign up here to receive this monthly update from the a16z fintech team in your inbox.