COVID has strained our healthcare system, payors are feeling the squeeze of rising costs, and patients are bearing the brunt of the current system’s shortcomings. As a result, healthcare is undergoing a transformation, from care that is predominately fee for service and based on volume of care to value-based care. Risk-based contracts are critical to building businesses based on risk and value, rather than fees and volume. We talked to digital health builders — from Firefly Health, Pearl Health, Waymark, Carrum Health, Eleanor Health, Patina Health, and BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina — at the forefront of the shift to value-based care about how to build risk-based companies.

- The spectrum of risk-based models [1:33]

- Where we are in the shift to value-based care [3:37]

- Deciding to go at risk [5:46]

- Establishing partnerships [13:03]

- Defining success [19:14]

- Scaling [24:16]

- Investor perspective [29:46]

For more on building digital health companies: a16z.com/digital-health-builders.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Transcript

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Julie: Hi, I’m Julie.

Justin: And I’m Justin.

Julie: And welcome to the second piece in our series on new go-to-market motions in digital health. For our first video, we looked at the B2C2B go-to-market approach. In this video, we’re going to dive into how digital health companies are driving towards value-based care using risk-based contracting.

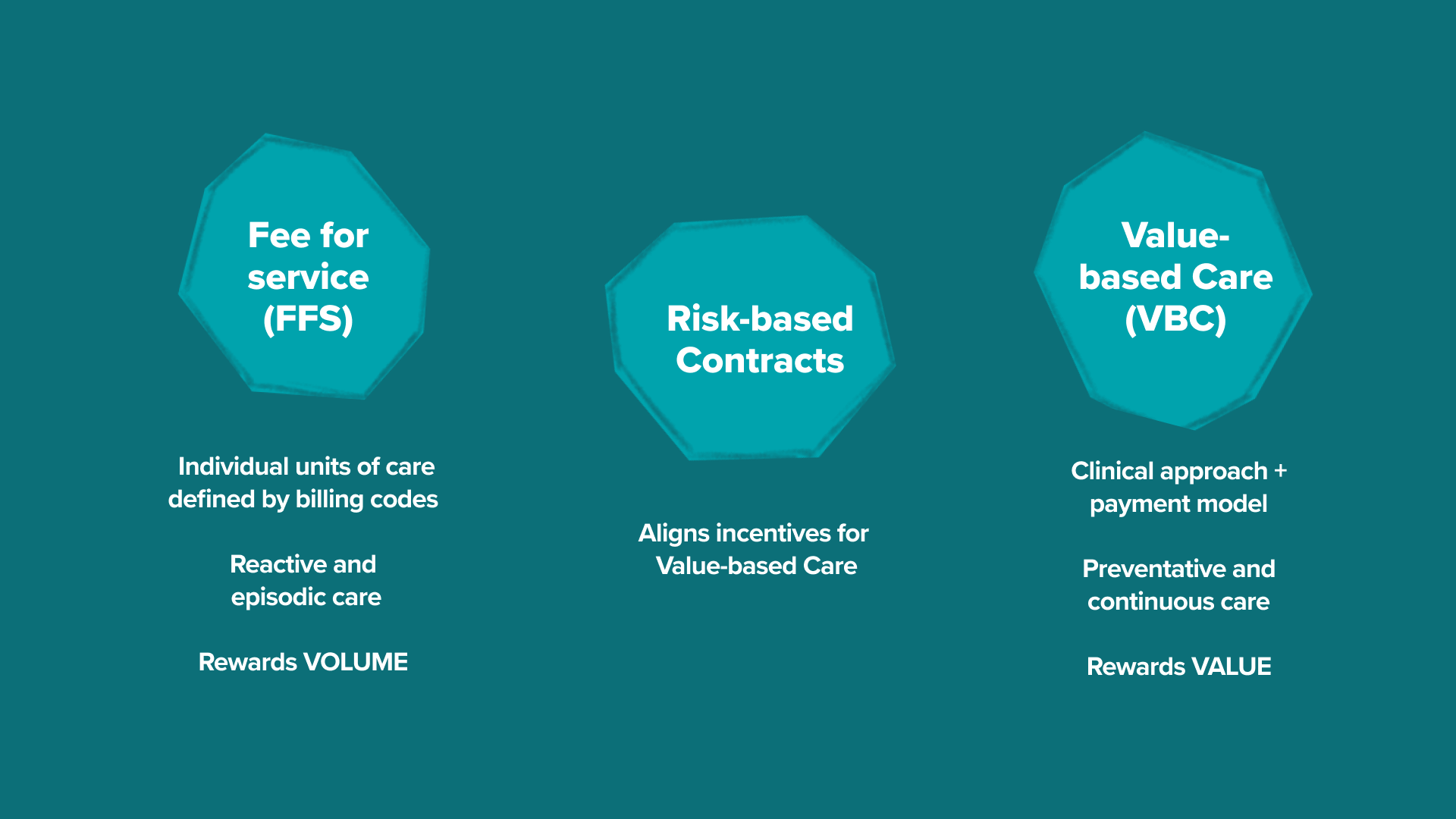

To understand risk-based contracting, let’s first unpack: what is value-based care? Value-based care, or VBC, is both a clinical approach that focuses on preventative services and long-term health care outcomes and a payment model that enables the appropriate incentive alignment to achieve those clinical goals. It’s oftentimes thought about as the antithesis to the traditional fee for service payment system, in which providers are paid for individual units of care using established billing codes.

These payor-provider contracts have really driven these fee for service rates through the roof, and that’s been a major driver of why our nation’s healthcare costs have skyrocketed to nearly 20% of GDP without a commensurate rise in clinical outcomes and patient experience. This push towards value-based care is really a push to align value creation with value capture. And that’s really where risk-based contracts come in. They are a reimbursement mechanism that aligns incentives. Rather than providers being paid based on higher volumes and individual procedures and services, providers are rewarded for hitting certain quality and cost outcomes and measures.

The spectrum of risk-based models

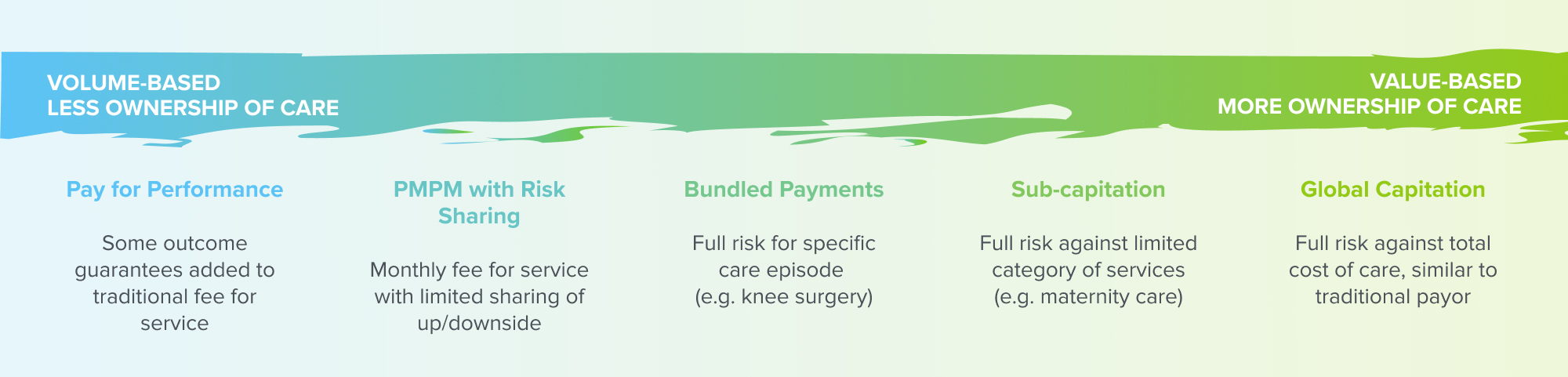

Justin: We often talk about going at risk as if it’s a single approach, but the reality is that risk-based models represent a broad spectrum. As we move across the spectrum, a number of factors can change, but it’s primarily the fundamental unit of payment and the degree of ownership or accountability that a company takes on for a given patient or given patient population.

These different factors ultimately manifest in various types of risk-based models. The first bucket is pay for performance. It’s something that rides on traditional fee for service rails, but often has some kind of clinical or operational performance guarantee that’s layered on top.

The second bucket is PMPM, or per member per month. This is a model where a company will often charge a set amount for clinical services, so they might receive $5 or $50 or $150 per member per month, but coupled with that is a risk-sharing component, where there’s some limited sharing of economic upside against the total cost of care.

As we continue, the third bucket is bundled payments, and this is a structure where companies take on full risk against all of the care for a given patient for a specific episode of care. That episode is typically defined by a certain time period or type of services — that might be something like a bundle for maternity care or a bundle for knee replacement surgery.

Then we get into capitation models, and in a capitated model, a company or a provider takes a flat rate of payment for a patient, while taking on full risk against a wider range of services than we saw in bundled arrangements. In a subcapitated model, the company is taking on payment and risk for a subset of clinical services. For example, they might take on payment and risk for all primary care or all outpatient services, but in this example, not necessarily for hospital care or for other acute services or for pharmacy spend.

In the fullest version of an at-risk model, we have global capitation, where a company takes on full risk against the total cost of care, or in other words, for all clinical services for that patient. In models of global cap, companies are effectively becoming the payor as they take on this full actuarial risk for that patient.

Where we are in the shift to value-based care (VBC)

Justin: Where are we in this macro level shift from fee for service to value-based care? In 2021, fewer than 40% of healthcare dollars actually flowed through a payment model that had any kind of substantial value component to it, and only 6% of dollars were in subcapitation or global capitation arrangements. That being said, we’re constantly hearing about risk-based contracts and value-based care. They’re in the zeitgeist, and that really has to do with a number of different things.

One of those being that over the past couple of years, COVID has hit the health system like a meteor. It’s really exposed the general lack of resiliency of a predominantly fee for service system, not just in the incentive and reimbursement models, but also in the ability of fee for service models to absorb unpredictability. At the same time, it showed that those with higher exposure to value-based contracts were often better positioned than those who are completely dependent on fee for service revenue streams.

Even more broadly, payors are continuing to feel the squeeze of rising medical costs, and because of this and are doubling down on risk-based and value-based models. For example, just this last year we heard from CMS, which is the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services, that they’re aiming to have all Medicare beneficiaries cared for by providers in value-based care models by 2030. At the same time, many traditional care models and providers just aren’t ready to take on that risk.

Excitingly and optimistically, purpose-built virtual care tech stacks have the potential to drive better risk management and more nimble care models that learn over time in ways that are difficult for traditional providers purpose-built for fee for service. Even though there are a number of companies that have struggled in risk-based models, there’ve been a number that have also defined the path of how to do this really well. We talked to digital health builders who have navigated risk-based contracts and who understand the specific challenges that come with building and scaling a risk-based go to market. In this playbook, we highlight their learnings with a focus on key phases of the builder journey — first is deciding to go at risk, next, establishing partnerships, defining success, and then finally scaling.

Deciding to go at risk

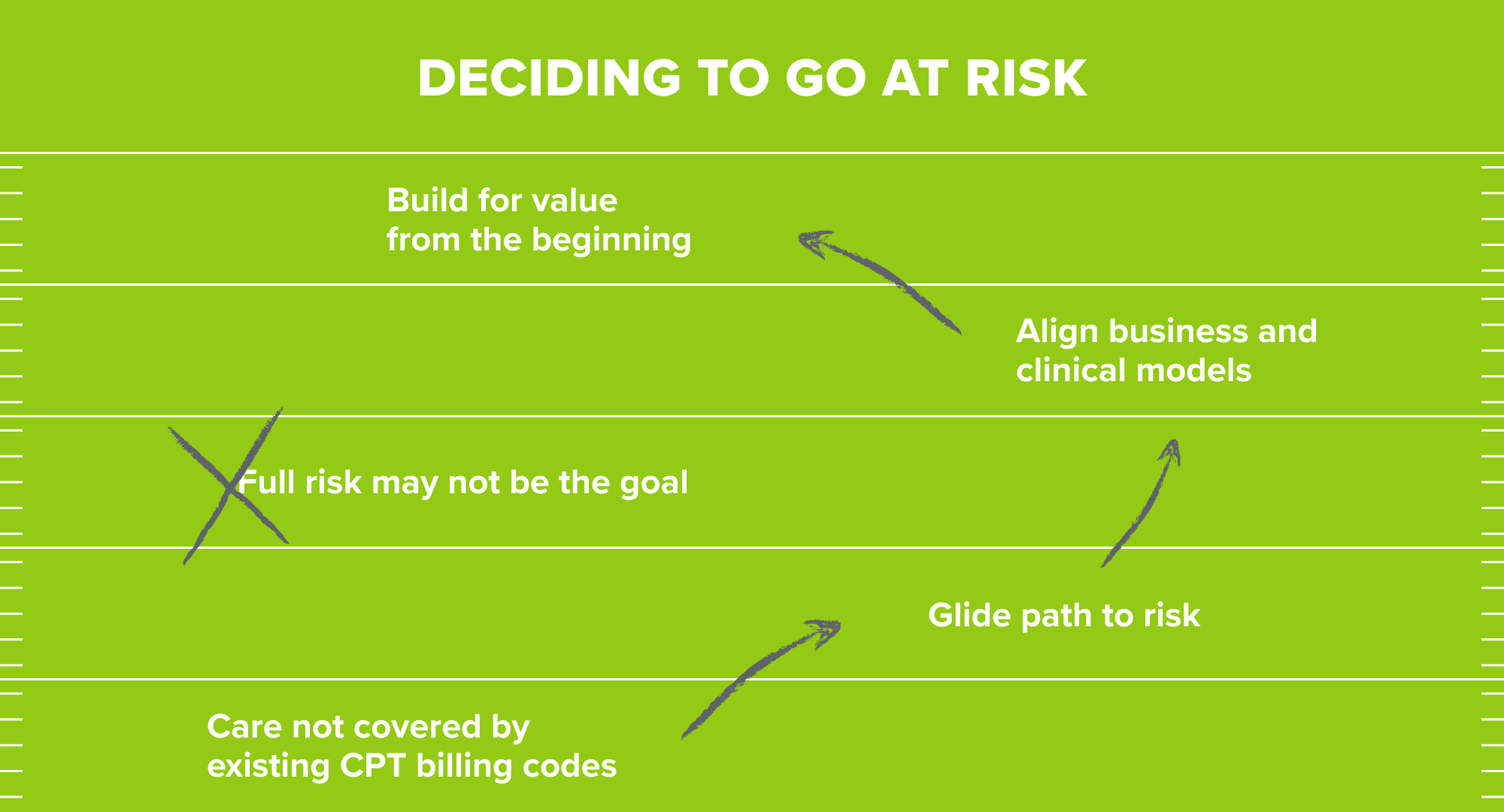

Justin: So jumping in, let’s hear how some of these founders grappled with the decision of whether a risk-based model was even right for their business. Like many of the founders we talked to, Jack Stoddard, who’s the CEO of Patina Health, which is a virtual-first and home-based primary care model for older adults, accelerated their path to risk because they had to.

Jack: When you’re coming to market with an orthogonal view of the world, often it doesn’t fit into the existing business model constructs. Specifically, in primary care, the market is used to paying only 4-6%. Our belief is if you invest more in primary care than you can actually take out waste in the other 96% of health care. Because our model is counterintuitive to how the market has always approached it, we said, “look, let’s be accountable for outcomes, and let’s ultimately build this for risk.”

Justin: Risk-based models can provide more freedom to define the care model. This freedom can give space to prove out the impact of these novel care models, but at the same time, this path to risk has to be balanced with the potential downsides. Many of the founders we talked to took a glide path or a phased approach to risk. Let’s hear from Rajaie Batniji, the CEO at Waymark, where they’re building a value-based community-driven care model for Medicaid. They took an accelerated path to risk, but Rajaie highlights where a glide path approach may make more sense for a company

Rajaie: Risk is opportunity. Risk is also freedom. It’s the freedom to try new things, the freedom to break the bounds of what is the status quo or conventionally considered the approach. Risk is opportunity, but it’s also risk, and there’s enough risk in building a new company.

I would not recommend moving toward risk simply for some kind of valuation arbitrage. I think you do it because it’s needed to prove a new model of care, or it’s needed to cover something that’s just simply not paid for under existing CPT codes.

Justin: We heard something similar from Corbin Petro, the CEO at Eleanor Health, where they’re building a hybrid value-based care model for substance use disorder.

Corbin: In our space, what we know and what the evidence tells us is that creating meaning and purpose in people’s lives really helps retain them in recovery and support their mental health and wellbeing. Well, there’s no CPT code for creating meaning and purpose in people’s lives. You have to figure out another way to address that, and the clinical model and the business model go hand in hand. You can’t sustainably deliver the clinical model without the business model piece in place.

Justin: Taking on risk is a powerful opportunity to create alignment between the business model, the care model, and the operating model, but it’s also inherently risky. Many companies ultimately decide to take a glide path to risk, but where on the risk spectrum is the right place to start?

Rajaie: You probably arrive at the level of risk based on what levers you need for the model to work. For example, if you needed to control in your care model all of utilization management, the claims payment, and network design, there’s probably no other way for a payor to let you have those keys other than moving to a true global cap.

Jack: It’s difficult to jump straight to full risk. Most payors are gonna look for you to have enough experience and enough patients and, frankly, enough financial weight behind you that you actually have the ability financially to take and manage risk. To do that, I would say start slow, try to align your incentives with the payor where they want to help you get to full risk.

Justin: But even if you start on the glide path with fee for service, it can be really hard to build for fee for service and for the ultimate goal of value-based care in parallel, as we’ll hear from Fay Rotenberg, who is the CEO at Firefly Health, where they’re building a health plan on top of a virtual first value-based care model. They started with fee for service contracts, but they built for value in the operating and care models from day one.

Fay: Day one Firefly launched with really basic contracts with payors in Massachusetts, and by basic, I mean fee for service. That was never the business we wanted to be in, but it was what we needed to get going. We had basic fee for service contract with payors, and really all that meant was that we were in network with them.

Even if it meant not getting reimbursed for all of the ways we were interacting with patients, in many ways we were operating as though we were on value-based contracts even before we were. We relatively quickly progressed from those basic fee for service contracts to more strategic subcap agreements, and we were able to do that off the early experiential data that we were able to provide to payors from our initial members.

Corbin: You hire people who are mission driven. They don’t want to give half the population one thing and half another thing, and so we decided our north stars are our outcomes. Let’s really focus on getting a lot of proof points and a lot of data showing that our clinical model provides superior outcomes. We started then consistently delivering our care model across reimbursement types, fee for service and value-based.

Justin: Now we often get the question from entrepreneurs and providers is the ultimate goal for everyone to get to full risk, to get to something like global capitation? As we’ve heard before, though, what amount of risk you take on ultimately depends on what levers you can control on the clinical side and what ultimately best aligns your care, your operating, and your business models.

For example, in primary care, care is more continuous. It’s more longitudinal. It covers a broader set of levers and conditions. For that, global cap often makes the most sense. On the other hand, other more isolated specialty conditions might be a better fit for subcap, where they take on a narrower aspect of care and risk for that patient. For more episodic care like surgical episodes, it can be best optimized through bundled payments. Let’s hear now from Sach Jain, the CEO at Carrum Health, which is a marketplace for high value care.

Sach: Surgical care felt like the natural place for us to start because the span is highly episodic, and the cost and quality variation is significantly high in surgical care delivery. We felt that was ripe for bundled payments.

Justin: For Carrum, taking on additional risk only adds operational complexity.

Sach: If you’re taking an insurance risk in healthcare, you are governed by very different regulations that are very onerous. Taking any kind of risk means your capital requirement to start the business goes up significantly. We just felt, given where we were, we didn’t want to raise that kind of money in those early days. Creating a model where we essentially stay risk neutral gave us a faster path to market.

Establishing partnerships

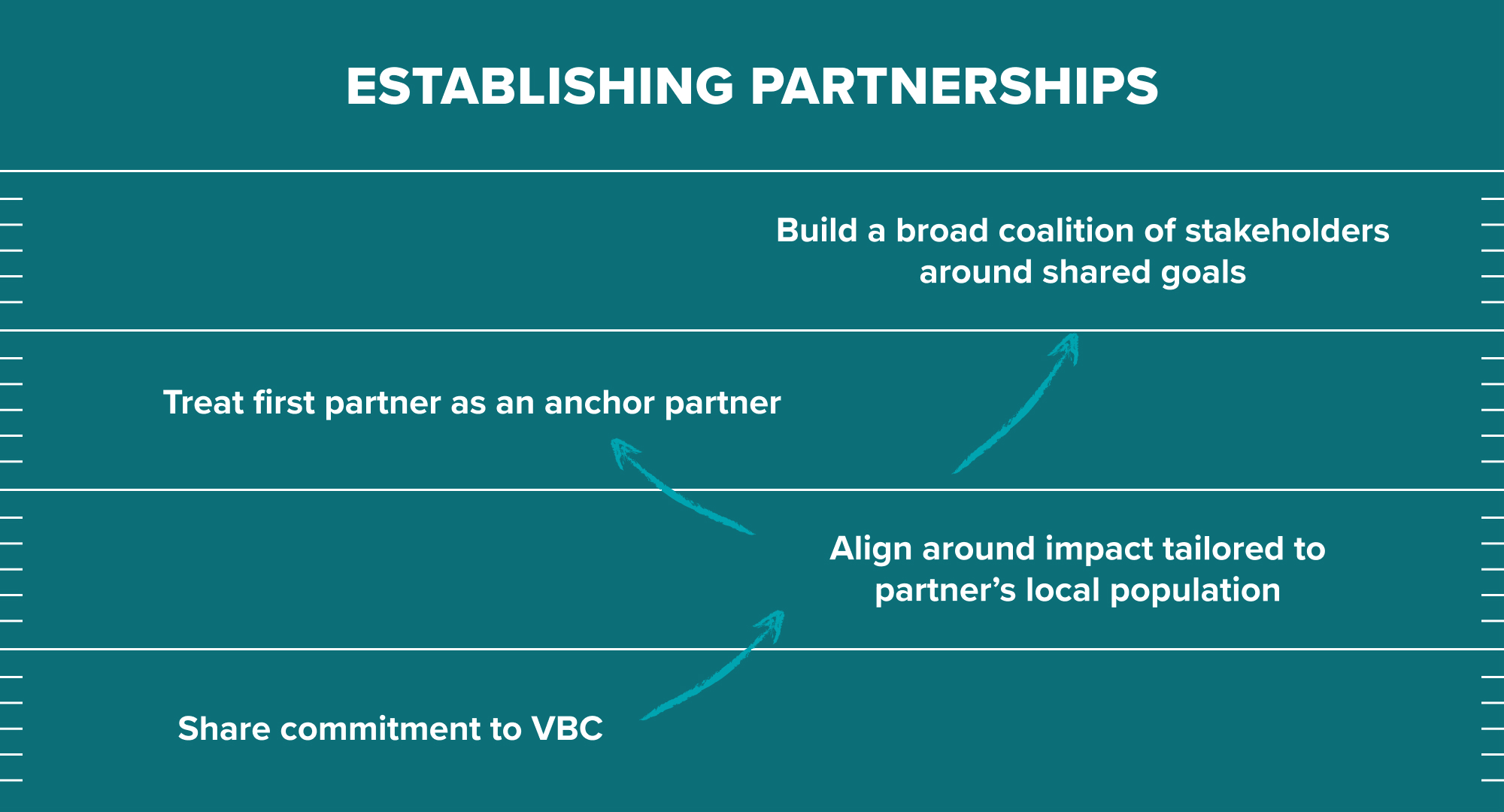

Justin: Wherever on the risk spectrum a company decides to start, success in at-risk model fundamentally depends on aligning with other great partners, but in a complex landscape of different potential partners, how do you think about the right set of partners to start with?

We’ve consistently heard across founders and across our payor colleagues that vision and mission alignment are critical, especially early on, and that ultimately starts with aligning around the clinical areas of impact that are most important, as well as sharing a commitment to a value-based approach.

Let’s hear from Mike Kopko, who’s the CEO at Pearl Health, where they’re building a marketplace that partners with both risk-bearing entities and provider groups to help these providers take on more risk for their patients.

Mike: In healthcare, I think we’re in a very dark age still where which providers should be managing which patients is really a function of geography and often referral networks, and maybe someone that you looked up on the Internet. We would argue that over time, it’s actually gonna be much more around who is effective with risks and which clinical models manage which risk conditions effectively.

When we look at adding new partners, we want to work with partners that see the future that this type of risk-based management system is going to be around to stay and actually wants to encourage, reward, and in certain cases, create subsidies around participating in these early days of the shift to risk and value. A lot of our partners see that. They’re thought leaders on how to make that shift and, frankly, are helping us to make the cost of participating in those models and the reward of performing well in them very accessible for the physicians that are taking on that opportunity.

Justin: We’ve heard similar themes from our payor colleagues as well about how important it is in the early days to have alignment around long-term impact, specifically impact that is tailored to their local community. So let’s get the take from Sonny Goyal, who’s the Chief Strategy Officer at BlueCross BlueShield of North Carolina, and one of the biggest advocates and champions for new value-based care models.

Sonny: Having a deep understanding of our local population is really critical. We have found the most success with those partners that understand that while North Carolina may look like many other states out there, we are different and unique in a lot of ways as well. They get deep into the communities, into our local populations, and understand that you have to design the solution to really match the specific needs of our people.

Justin: Having strong, aligned first partners, your launch partners, is especially important as you’re getting your business off the ground.

Jack: I’m a strong believer in having an anchor customer to help launch a business. In essence, they become a co-founder who really understands your stage, believes deeply in your vision, and really wants the results that they think you’re going to be able to unlock. If you can get that alignment with an executive sponsor, predominantly one who has the P&L, who actually is going to benefit from that value that you’re going to create together, I find that they are the ones who can then help train your organization and be a river guide through the rapids of these health plans that are often somewhat difficult.

Justin: Speaking of navigating health plans, how do you get the right stakeholders to the table, especially in the early stages?

Rajaie: The good thing about the space that we’re in is these problems really matter to people. We’re not inventing a problem for them. We’re really helping them take on what they recognize as the most urgent challenge in Medicaid care delivery, which is: how do you deliver community-based care that meets people where they’re at? That’s usually enough to get the right people to the table.

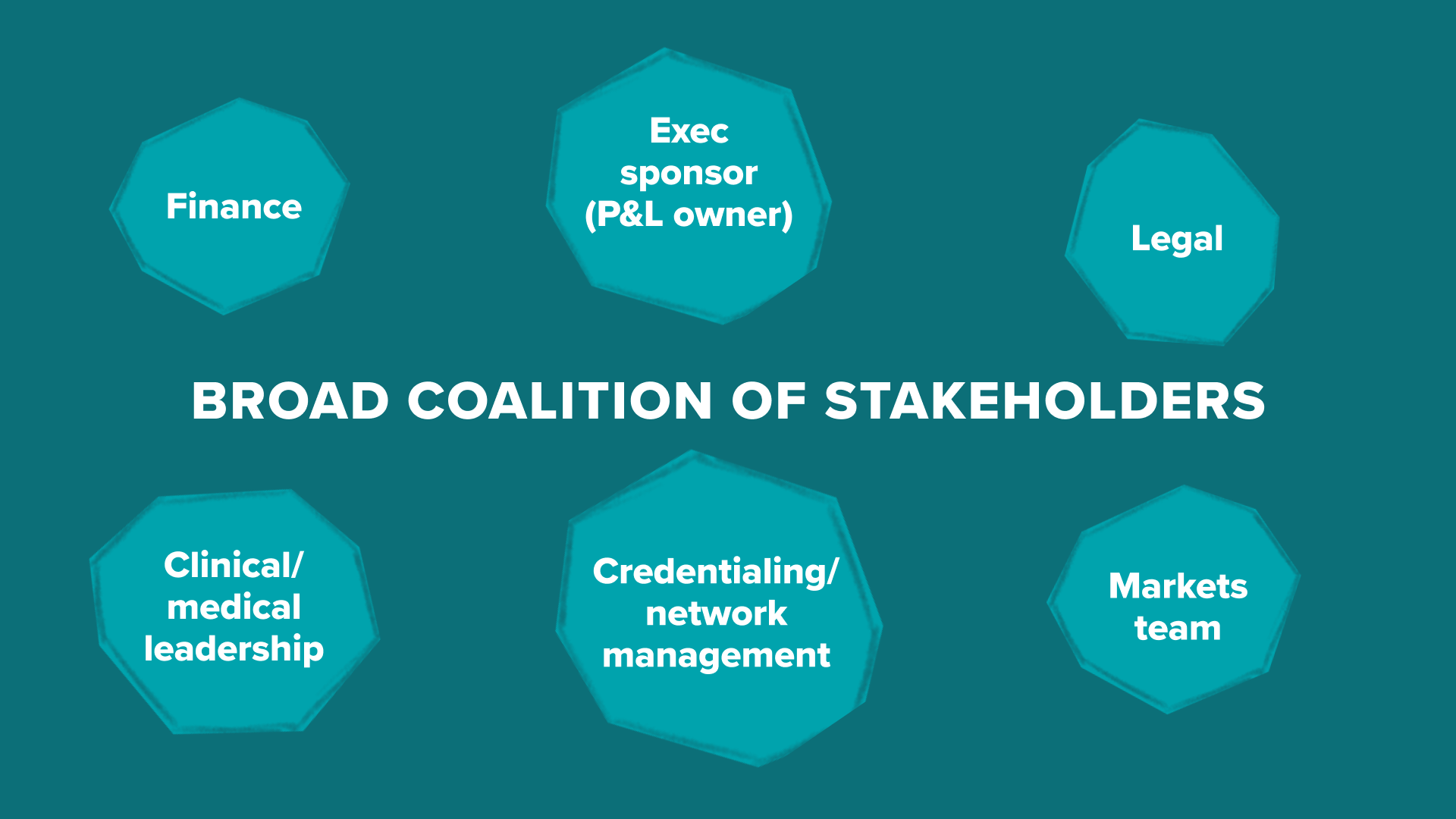

Justin: Who are the right people to have at the table? This will depend somewhat on the partner. For example, the needs of a large national payor can be quite different than the needs of a local regional insurer. But, in both cases, it’s better to build broad coalitions, both vertically with executives and business unit owners and horizontally across key functions.

Jack: In my experience, there are very few people in these payor organizations who can say yes, but there are a lot who can say no. Especially when you’re doing something that’s innovative, that breaks the mold, that challenges their existing processes, the further into the sales, contracting, and implementation process, the more you bump into other parts of the organization. Having a broad coalition that includes having a strong exec sponsor, preferably a P&L owner at the helm of this ship is most important. That coalition should include contracting, the medical leadership, often the credentialing team, even the lawyers who are going to be involved. If there isn’t that understanding, it becomes work, and you get a lot of these stakeholders downstream that are almost antibodies, and they can come back and try to attack this innovation.

Justin: Larger national partners, as some of the most complex organizations in healthcare, often require the broadest coalition building. Let’s go back to Sonny to hear the payor perspective on this piece.

Sonny: When we think about due diligence and who’s conducting it, a lot of time that actually is my team and my division around our strategy and our new ventures team. We are really set up for guiding innovators through all parts of our organization, critically, obviously engaging with our healthcare division, our clinical division, for the support and the experts to make sure that these things come to life and that they’re put into our networks and our processes and our procedures in the right way.

Then we are always working with our finance division because what we are driving towards is affordability. Then we go into our legal and our health policy teams, and a lot of times they make sure that we are driving in the right direction and lining up with where the government wants us to go, where our consumers want us to go, and really being thoughtful about it.

Then last, but certainly not least, is what we call our markets team, whether it’s our government team or a commercial team, for how we fit this into their products, into their services, for our customers, whether it’s the individual, through the employer, or through the government.

Defining success

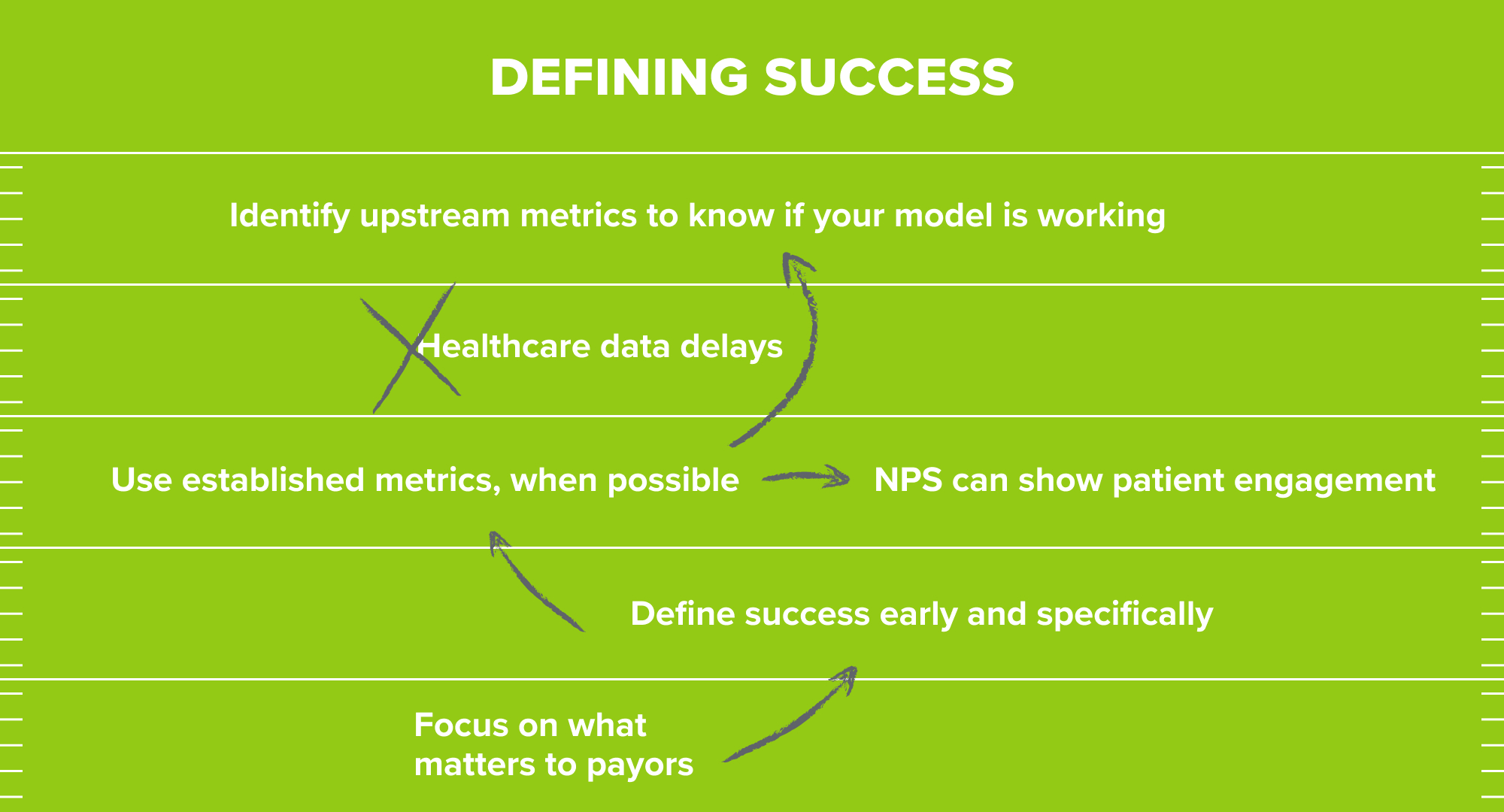

Justin: The first step in scaling at-risk go to markets is to succeed in early deployments, but by definition, success in risk-based contracts is ultimately judged against the value or outcomes that are created. Because of this, one of the most important steps in laying the foundation for scale is defining how you tactically measure success with partners up front. We’ve heard across founders and across our payor colleagues that you have to define success in terms of what matters most to each specific partner.

Sonny: We’re focused on affordability and really the total cost of care. You may have the best solution out there, but it may not be the biggest value or the biggest impact to what our members need and how we drive affordability. Sometimes innovators miss that because they’re focused on their solution and selling.

Rajaie: The question about defining success is not something that you get into at the end of year one of your partnership. If it is, you’re probably in trouble. There’s nothing more important than actually getting that defined and not just conceptually, but literally in an Excel sheet, looking at it and saying, “does this look like success to you?” And then working out contracts to follow from that.

Justin: Success is often defined on operational and cost outcomes, but picking clinical measures is a key component as well. We’ve consistently heard about the importance of picking measures that are both validated and easily comparable for your partners. For example, Eleanor Health focuses on substance use disorders for which there are established clinical measurements already in place that they can use.

Corbin: We focus on psychometrically validated scales and screeners, so we can benchmark against them and say how much better we are. That’s one thing, and certainly payors and others care about that. They also care about things that you can compare a little bit easier. We saw significant reductions in ED and inpatient that we collected through third parties, and so we were able to show in a statistically significant way that we were having this impact across our populations.

Fay: Part of getting members through these initial fee for service contracts was just getting enough members really to get enough data to demonstrate proof points, including experience. NPS actually mattered a lot to the credit of payors. That went a long way to actually show all of the engagement that we’re having with our members, which is an average of 41 touch points a year of clinically significant interactions. The ability to reduce TME (total medical expenses) on a fee for service contract, what that really meant was, how are you doing on ER admissions? Are you keeping people out of the ER? That was a big driver for us. How are you doing on A1C readings? How are you doing on behavioral health? On anxiety? We were able to take all of those things and bring them back to payors and renegotiate our original contracts to get into a PMPM subcap agreement.

Justin: Once you’ve established a successful anchor partnership, the next key question is when to scale those partnerships. One of the challenges of making these decisions in risk-based contracts is the inherent data delay that we have in healthcare. Even when the end measures of success are clearly defined, founders emphasized the need for upstream process and operating measures to help companies know if what you’re doing is working and is scalable, well ahead of the ultimate data readouts that come sometimes years down the line.

Rajaie: You may elect to ramp up a market before you have a final answer on whether or not it worked financially. Because with the run-out in claims and the reconciliation period, and even in Medicaid, retroactive government adjustments on rates, it could be literally 18 months until you have a financial answer on whether the model worked. You need to have the toolkit and the dashboards to know: Do we expect this to work? Is it working from the perspective of the nonfinancial indicators that we can feel confident?

Jack: Like most things in healthcare, it’s not a clear path between here and there, between A and B. You really need to move backwards and think about, if these are the end targets that you’re trying to hit — be it satisfaction, be it savings — what are the interim measures that you can use to get a pretty high degree of confidence that those things are going to emerge, if that’s utilization changes or quality impact or early indicators of satisfaction or savings. Then go even further upstream, to the degree which you have process measures in mind, are your processes defined? Do they have measures?

You have a hypothesis as you build your business around what steps you will take in the value stream to unlock that value. I would encourage you to continue to put metrics against those pieces, so that you can look at them and say, “Hey, we feel like we’re on the right path.”

Scaling

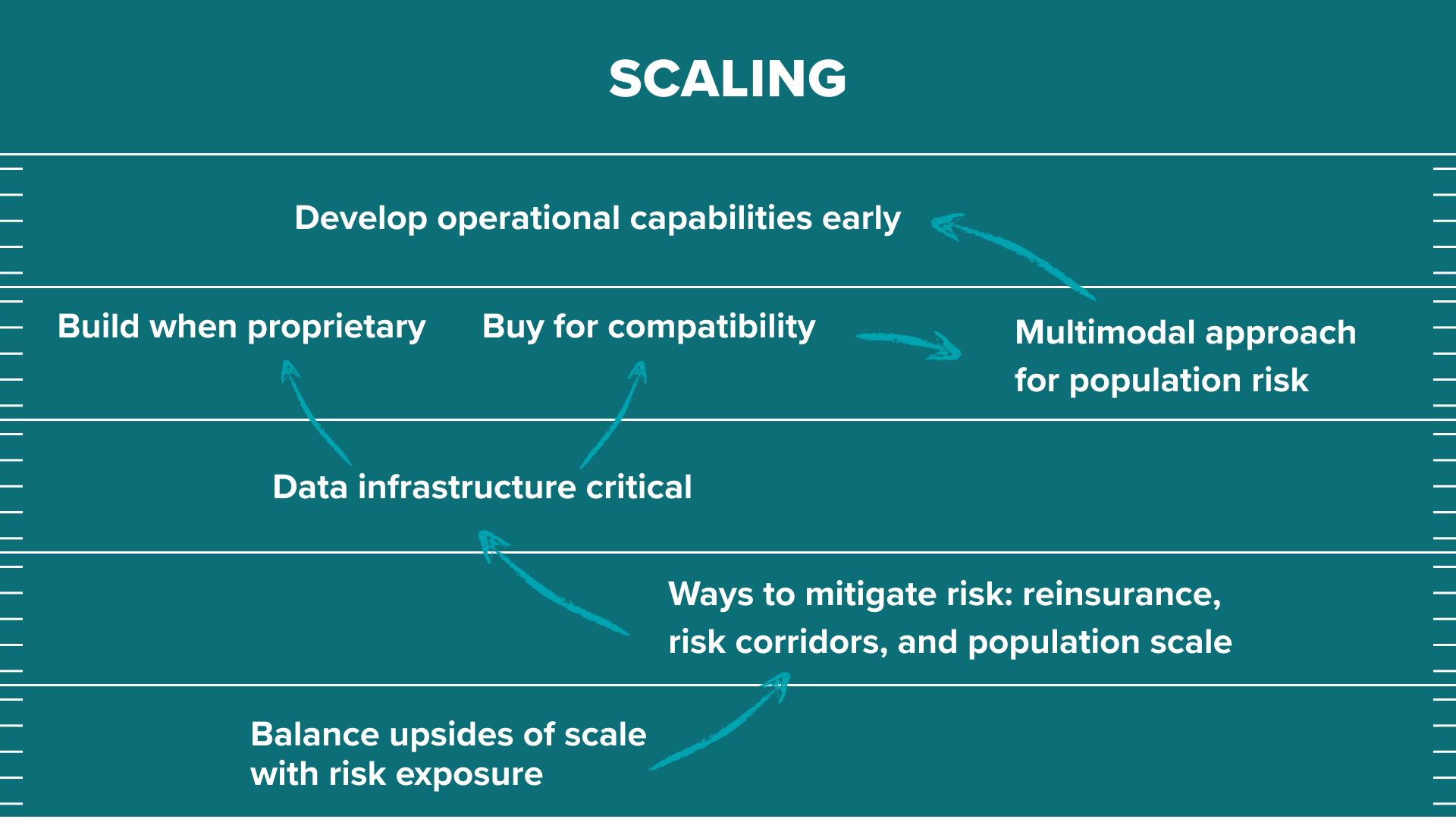

Justin: WIth those upstream process and operating metrics in place, how fast should you expand to take on additional risk or to take on additional patient populations?

Rajaie: There’s a balance between needing to be enough scale so that operationally, from a unit economics perspective, you can make it work, and that from an actuarial perspective, you have enough credibility. But not being at so much scale, or being so exposed in your risk, that if the model doesn’t work exactly as you hoped in year one it has a hugely negative financial impact on the business.

Justin: As you grow, there are also several approaches and strategies you can take to manage and mitigate the risks that a company is exposed to in value-based and risk-based contracts. For Pearl Health, this was especially important as they took an accelerated path to full risk.

Mike: The more sophisticated models are reinsurance and stop-loss policies. One that we think about and a way to help serve our market is the larger you get in these models, the more you except yourself from systemic risk. You can effectively defray that, and you have fewer exogenous factors that can be incredibly expensive. A small practice, for example, can have a big swing that is incredibly punishing, but a very large market like Pearl, where you have thousands or tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of members, is much more immune to those types of swings.

Justin: Succeeding in value-based and risk-based contracts comes down to having the right set of clinical and operational capabilities. As we’ve heard from multiple founders, it’s critical to build these capabilities from the earliest days.

Corbin: Technology and data are really important in order to take risk on populations. From day one, we set up a really strong data infrastructure. We were collecting data, both claims data from payors enriched by third parties, and then enriching it with our own psychometrically validated scales and screeners, so we could evaluate the impact of what we were doing.

Collecting that data, analyzing that data, and making changes to our care model for how we approach people, you have to be able to do that from a population perspective, being able to look at the claims data to say: Who are the most high risk members? How do we risk stratify? But, as well, being able to iterate and change your model based on the evidence that you’re getting and the data that you’re getting back from your own interactions and interventions with patients is really important.

Justin: In these early days, when you’re building your data infrastructure in your product, what do you buy and what do you build?

Rajaie: It can be a gamble to say that you’re going to build all that yourself, and so actually we’re pretty focused on build versus buy. What we wanted to build was really only the parts of the equation that no one else had created, that were proprietary to us, which is: how do we identify patients for engagement? How do we automate the care pathways? How do we give our community health workers that we’re training for the first time the pattern matching of somebody with years of experience? That all happens through our product that the team is building.

When it came to some of those core instrumentation pieces, it needed to be compatible with what our health plan partners were seeing. It needes to be compatible with what providers were seeing, and so, there we made decisions so that we could effectively be on the same playing field as them, and not be too creative — too far ahead, or too far behind — in how we were receiving and communicating data and information.

Justin: Beyond the data infrastructure and the analytical capabilities, scaling at-risk models often also requires being able to deliver care in novel ways, which often requires multimodal care, interdisciplinary care, and more continuous care approaches.

Corbin: We have brick and mortar clinics. We have field-based teams that can connect with our community members in person. Then we have a really strong digital infrastructure as well. I think not delivering just a point solution of one thing, but being able to address more of the needs of a population is important in these risk models.

Justin: This adds quite a bit of complexity to risk-based business, relative to it’s fee for service analogs. Because of this, we consistently heard from founders how important it is to have the right expertise around the table and to build these capabilities early on, as companies take off on the glide path to risk.

Rajaie: Short of it is, you have to bring in a lot of the expertise and process that you might see in a larger, later company earlier, if you’re going to move down this path, because the stakes are so much higher. You don’t do this because you think you’re going to have an outcome that you can point to in 12 or 18 months. You do this because you think that over a many year period, potentially a decade or more, that you’re going to make a real impact on care delivery. You have to have that patience and time horizon. Everyone on our team has it, and I think, equally important, our investors have it.

Justin: While it’s still early days for value-based care and digital health, we’re already seeing how it can rewire our healthcare system and also the patient experience within our healthcare system. As risk-based digital health companies grow, some of them become marketplaces or enablement layers that span between payors and providers. We’re also seeing others that are effectively becoming payors themselves, as they take on global capitated risk and partner with a range of other providers. And then others are on paths to become care platforms with a broad range of clinical services.

What we look for as investors

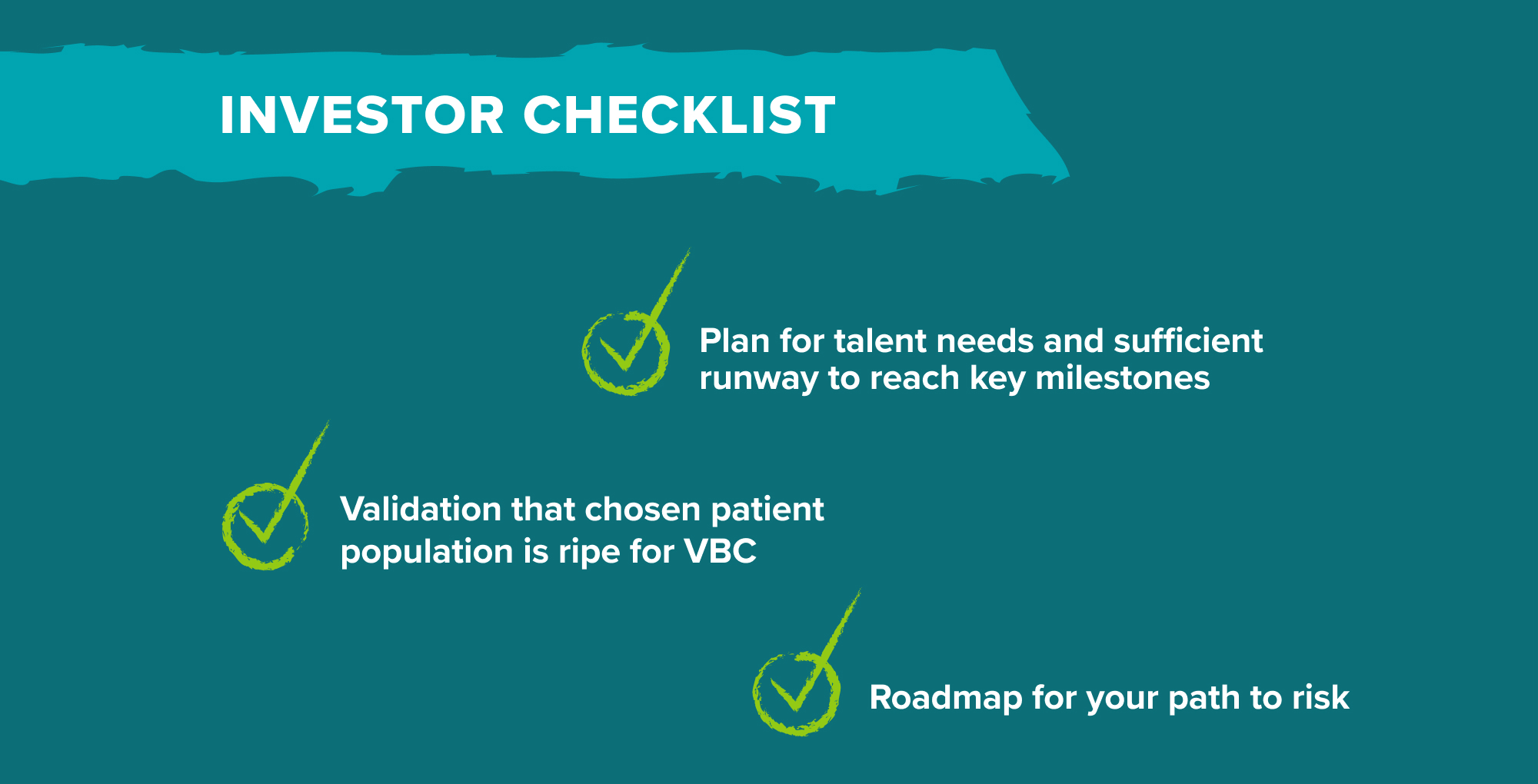

Julie: So, how would we look at these companies from an investment lens? We heard earlier how these risk-based contracting models will generally require a fairly non-trivial set of investments into both the clinical aspect of the business and risk management. First and foremost, we’d simply want to know, does your plan appropriately account all the necessary components? For instance, we’re going to look at the talent on your team and whether you have internal experts or plan to hire folks who have implemented value-based care models in the past and ideally also successfully negotiated risk-based contracts. Different levels of risk will require different levels of capital reserves, whether statutory or otherwise, so does your use of funds plan give you sufficient runway to get to a strong set of milestones for a follow-on round down the road?

A second thing we’d look for is whether you’ve selected a patient population for which value-based care makes sense. The market readiness for value-based care in different areas of the market is highly variable and also a moving target. Validation that you’ve chosen an area where the timing is likely right is super critical. Related to that, there could also be regulatory tailwinds that are relevant to your population. We’ve seen this with kidney care, with primary care, with oncology.

Finally, a third area that we would evaluate is: what are the actual plan and roadmap to get to full risk, or whatever level of risk you ultimately seek to take? How do you generate a sufficient set of clinical evidence to be able to sell those outcomes to payors? Even if you’re starting with simple fee for service contracts, having a well articulated roadmap and a set of assumptions for what you’d have to believe to get to higher levels of risk over time is something that we’d love to see in the earlier phases, including things like pricing and margin assumptions and some sort of thesis on TAM. Relatedly, we’d want to know: do you have payor partners either lined up or a hypothesis about which payor partners are ready to collaborate with you for the given patient population that you’re focusing on?

Thank you so much to our founders and payor executives who shared their perspectives in this piece on risk-based contracting for digital health companies and to all of you for joining us. We’d love to hear from you if you have any thoughts or questions and hope that you’ll continue to follow along as we roll out the rest of our go to market playbooks.