Over the past several years, the field of fintech infrastructure has exploded with venture capital investment and entrepreneurial attention. Between the emergence of Stripe, Plaid, and other category-defining decacorns; the continued launches of financial services offerings from non-banks like Apple and Walmart; and the general API-ification of the average tech stack, there are many structural tailwinds propelling fintech infrastructure forward.

We see this firsthand on the fintech team at a16z. Every week, we have the privilege of meeting dozens of incredibly sharp founders who are tackling everything from domestic adjacencies to existing offerings (e.g., payroll connectivity or health insurance aggregation), to international versions of U.S. success stories (e.g., bank account aggregation or global know your customer (KYC) tools), to novel problem sets entirely (e.g., bridges between web2 and web3).

As we’ve said time and again, we at a16z believe every company will become a fintech company. With this in mind, we’re laying out four key components that all infrastructure entrepreneurs operating in this space—whether they’re still in the idea maze or already in market—need to consider as they build their companies. We also present three forks in the road where founding teams will need to decide which way to take their business.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Must-Haves

TABLE OF CONTENTS

There are many approaches to building infrastructure, but we believe these four strategies are vital to ensuring your company has a solid foundation and a path to scale.

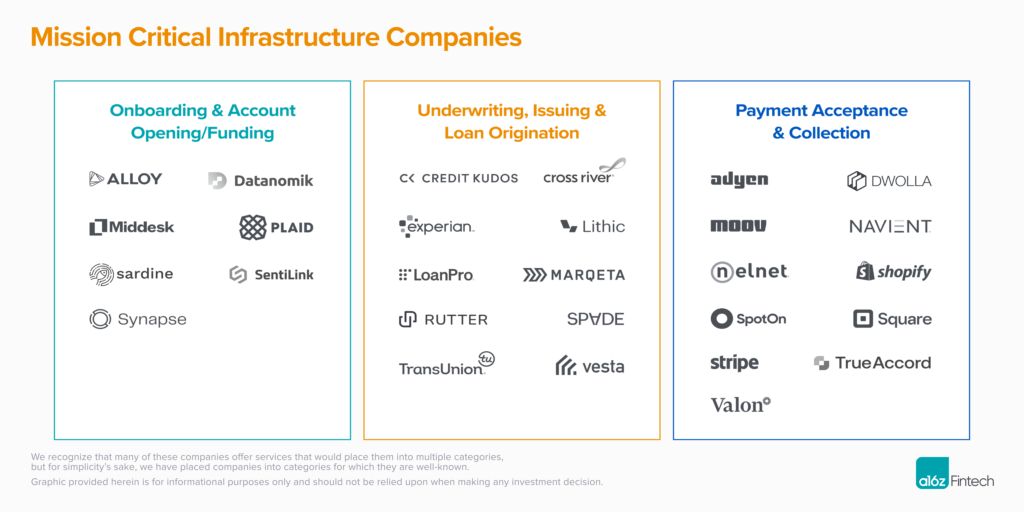

Mission criticality: Would your customers be materially disrupted (or even forced to halt operations) if your service went down? Or are you merely a nice-to-have? The answers to these questions directly determine the pricing power, defensibility, and overall stickiness of your product. The deeper you’re embedded—and oftentimes, the stricter your uptime SLAs!—the harder it is to replace you. While certainly not all successful infrastructure businesses will become 100% mission critical, we believe it’s easier to drive higher customer LTV when the core service you provide is absolutely essential to day-to-day operations. Typically, within fintech, this means that your product is a key enabler of either onboarding and account opening/funding (e.g., Alloy, Middesk, Plaid, Sardine, Synapse); underwriting, issuing, and loan origination (e.g., Adyen, Credit Kudos, Experian, FIS, Fiserv, Lithic, Marqeta, Spade, TransUnion, Vesta); or payment acceptance and collection servicing (e.g., Moov, Navient, Nelnet, Shopify, SpotOn, Square, Stripe, Valon). We recognize that many of these companies, such as Stripe, offer services that would place them into multiple categories, but for simplicity’s sake, we have placed companies into the categories they are best known for.

If you’re a fintech infrastructure entrepreneur building outside of these core capabilities, we encourage you to be honest with yourself about where you fall on the mission criticality spectrum, and identify opportunities to make your product irreplaceable. One such opportunity might be to re-think your customer set, as sometimes your company can be mission critical to one set of customers but not to others. For example: while transaction enrichment startups like Spade may have initially assumed their most obvious use case would be with personal financial management and budgeting tools, they quickly realized that the capability being offered—a cleaner and more satisfying UX—was mostly a nice-to-have and not directly linked to the top or bottom line. However, when they began selling to an entirely new category of customers, including BaaS providers and cash flow-based underwriting tools, they realized that what they were offering became absolutely critical, as it unlocked valuable net-new information about a consumer’s spending habits—and therefore their likelihood of repaying debt or committing fraud. Spade continues to sell actively to both customer segments, but the distinction in value proposition between the two is important to note.

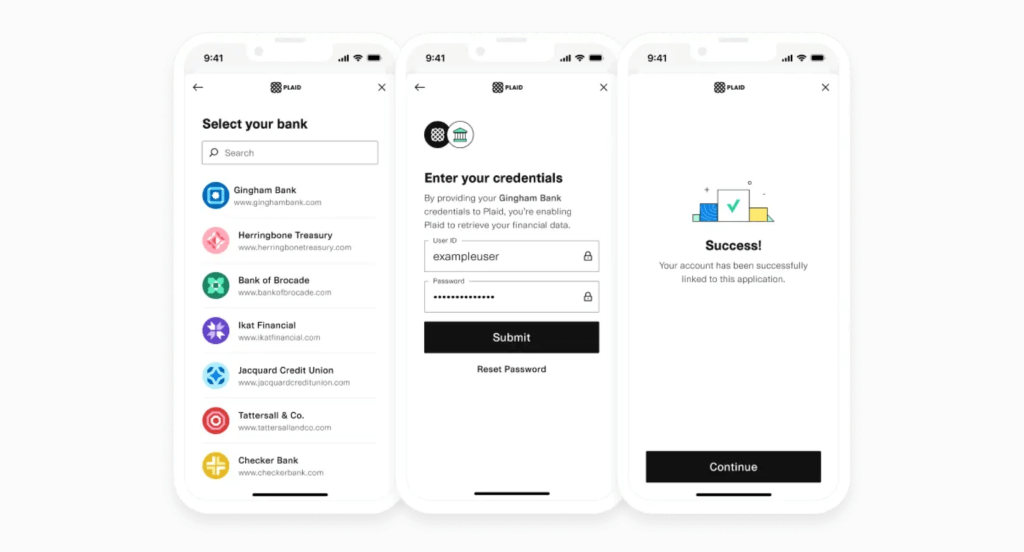

A narrowly defined initial use case: To get from 0 to 1, it’s our opinion that solving one discreet pain point significantly better (or cheaper!) than anyone else is superior to building proprietary IP that has many potential use cases, especially if none of them are clear on day one. Plaid did a phenomenal job of this; it set out to facilitate basic account aggregation with broader coverage and offer a better developer experience than what the incumbent solutions had in market. While Plaid could have immediately gone full throttle after all the use cases enabled by better open banking connectivity (e.g., lending, investment aggregation, money movement, etc.), it very deliberately built its core business around account opening and onboarding (the /auth, /identity and /balance endpoints) for neobanks and payments wallets. By serving thousands of customers with this core solution, Plaid quickly and efficiently built a massive proprietary data asset, upon which it could then start to experiment with new solutions to attract new customer personas and drive higher existing customer LTV. By solving one distinct pain point better than the competition could, Plaid established trust with its customers, which naturally opened up expansion opportunities to broaden its surface area. Had its initial product been built to accommodate too many use cases too early, Plaid might have been challenged by muddier value propositions, a lack of focus, disjointed sales cycles, and a more challenged execution (disclosure: Marc is a proud Plaid alum!).

Plaid Link Flow:

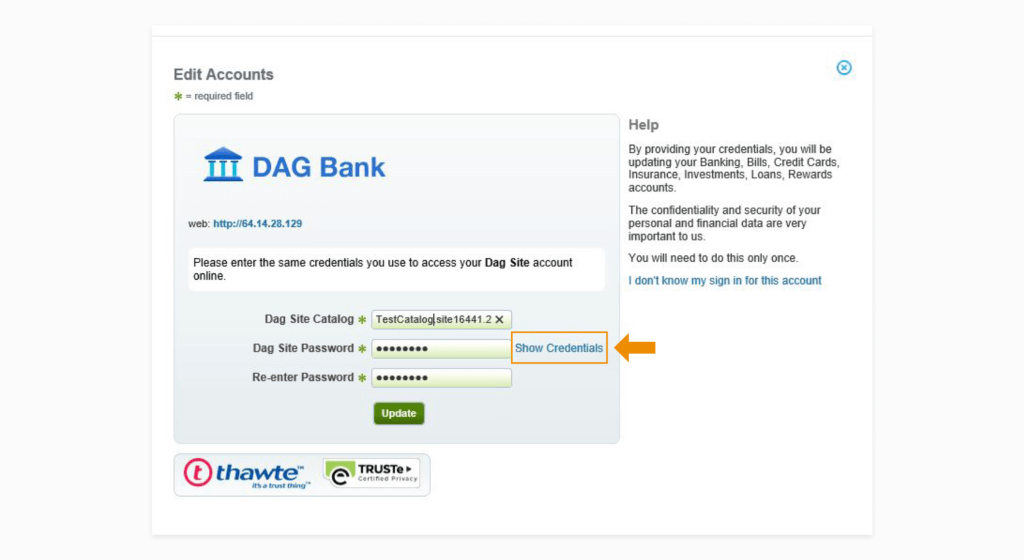

Old Competitor Flow:

Neutrality across customers: If you’re doing your job well, you’ll likely have many tough decisions to make with respect to deepening your relationship with anchor tenants. Sebastian Kanovich, CEO of the global payments company dLocal, discusses this dilemma very eloquently on the February 24 episode of the Founders Field Guide podcast with Patrick O’Shaughnessy. In the early days of dLocal, many merchants wanted to advertise their product to dLocal’s user base in exchange for direct payment or a larger contract. While it was surely a tempting offer (especially for a startup that had managed to secure massive customers like Uber and Nike early in its journey), the offer would have likely precluded dLocal from going on to serve other important enterprises (Lyft or Adidas, for example) that competed with these early customers. This neutrality becomes especially important when your business is vying for the new crop of default-global companies we at a16z are so excited about. With many new companies looking to compete internationally from day one, surface area for conflicts of interest is only becoming broader. With this in mind, we think it’s important to remain neutral; as a platform and infrastructure provider, you will need to treat all your customers as equally as possible. The moment you break your company’s branding principles, pricing bands, or product design policies to bend over backwards for a big logo is the moment you begin to jeopardize the rest of your customer relationships. Despite NDAs and confidentiality provisions, customers always talk to one another—especially when it comes to price!

Consumption-based pricing: We recently wrote an entire piece in defense of pay-as-you-go pricing. To summarize: license-based businesses tend to yield steadier growth and more predictable revenue (every SaaS investor’s dream), while usage-based businesses are more susceptible to market peaks and troughs, and therefore, commonly thought to be riskier. However, while the latter may not be as reliable for true annual recurring revenue, it can result in more revenue and better customer retention over time (especially when paired with thoughtful minimum commitments in master service agreements (MSAs)). Another advantage to usage-based pricing is it aligns cost and value, resulting in zero friction for increased real-time adoption of your product.. Whereas procuring additional SaaS licenses or a new all-you-can-eat deal requires a customer to go through an additional negotiation and/or contractual amendment, consuming more APIs (reflecting end-user growth and demand) can happen with no involvement from a sales team or account manager. Common examples of pay-as-you-go models include SpotOn, Stripe, and Square charging a percentage fee of the payment volume that they process, or E*Trade and Interactive Brokers charging a flat fee for each options contract traded on their respective platforms.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The Forks in the Road

TABLE OF CONTENTS

After you’ve ensured your company is cooking with the right main ingredients, you’ll need to consider which flavors will round out the dish. Any of the options presented below can result in a Michelin-star meal – it just comes down to style and preference.

Should you target developer-first or business-first buyers? In our experience, the developer-first motion—bottoms-up customer acquisition, self-serve onboarding, community engagement—tends to call for a product that provides clean, workable data as opposed to pre-configured modules or applications wrapping the data. Developers typically want to build their own analytics and UX as their “secret sauce,” whereas business-oriented buyers often want something more fully baked to address their immediate need in a more plug-and-play fashion. The latter buyer persona also typically requests myriads of customizations baked into the product, whereas developers are happy to start tinkering with the product as-is and build their own customizations down the line. Each approach has its pros and cons.

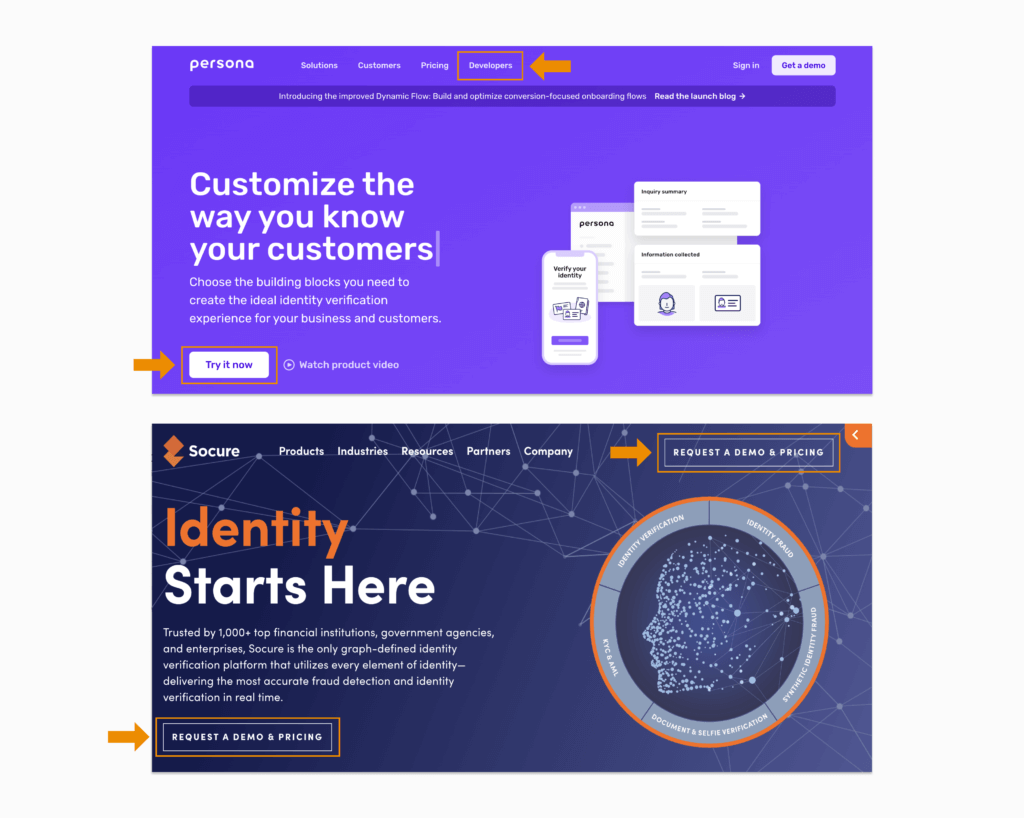

Consider here the difference in approach of Persona vs. Socure, two companies operating in the KYC space. For the ambitious developer seeking to build a fully customizable identity verification experience as part of their company’s onboarding flow, Persona markets “building block” and “mix and match” capabilities all over its homepage (see image below), while highlighting “Try it now” as the main call to action and providing a “Developers” hub with links to API documentation and a status dashboard. Socure, on the other hand, runs a more business-oriented go-to-market approach, in which the product is often referred to as a “platform” and the main call to action is always to “Request a demo & pricing,” aka, talk to sales.

It’s important to note that developer-first vs. business-first refers to the persona (no pun intended) of the typical buyer within an organization, and not the size or type of the organization itself. If you continue perusing the Persona and Socure websites, you’ll notice that both companies have successfully sold to customers of all shapes and sizes; Persona has clearly architected its brand around developers, yet boasts many large-enterprise customers like Square, Toast, and Carvana on its homepage. It’s easy to assume that startups, mirroring the developer community, prefer to buy core infrastructure building blocks they can then shape into a product themselves, and that enterprises prefer buying more fully baked, off-the-shelf products, but the reality is that purchasing depends largely on which team within an organization is pushing hardest for the product. We would argue that big businesses can be built for either audience, and in fact, over time, you’ll likely have to cater to both. It’s just a matter of deciding where to start and how to initially position your brand.

Should you optimize for speed or scale? Is the primary utility of your product offering customers a fast, standing start, or is it a foundation upon which they can build for years to come? Will your precious first customers and early design partners choose to build this capability in house once they’ve grown headcount and secured more bandwidth, or will they prefer to abstract it away to you in perpetuity? We think about this as “graduation risk,” and more often than not tend to favor businesses that entrench themselves as a permanent solution rather than a V1 or stop-gap measure. Having said that, there are of course many startups who can facilitate both speed and scale. It ultimately just comes down to price and complexity.

Should you offer a consumer-facing brand or a white-label experience? In a venture ecosystem where the promise or achievement of “network effects” is often the golden ticket to funding, it may be tempting to slowly but surely disintermediate parts of your customers’ business in an attempt to build a multisided network. Doing so often requires infrastructure companies to transition from white-labeled to branded experiences, since consumers likely didn’t know they were interacting with your product or service in the first place. Barring very unique circumstances, we caution against this—competing with your customers and imposing your brand into their user experience is often a leading cause for churn (or at a minimum, for scanning the market for a more pliable alternative). If, however, making your brand more prominently known could attract more end users to your business customers, this approach may actually make sense. Look no further than Plaid (again) for another example. While Plaid originally started as more of a white-label experience, over time it created a very deliberate consumer-facing brand that was architected around privacy, trust, and security. This was so that consumers would feel more comfortable linking their bank accounts to third-party apps and services when they saw the Plaid logo. In short, both approaches can work here, but it’s often a delicate balancing act when transitioning from one approach to the other.

There are many ways to build a fintech infrastructure company, and we’re lucky to be working with players of all permutations and combinations. So long as you’re working towards a clearly defined, mission critical use case while aligning value with cost in an impartial manner, you’ll have plenty of room to iterate on the details.