When capital becomes more expensive, how do you evaluate and decide on the best financing option for your company?

There is (or at least there should be) a VC industry saying: “Give me your headline price, and I’ll give you a deal.” The idea here is that founders tend to think in terms of valuation and dilution, while an investor might be more interested in knowing their minimum guaranteed return on the downside and the size of potential returns on the upside.

In a normal market, investors sometimes, but less frequently, use contract terms—such as liquidation preferences that are greater than 1x, warrants, and anti-dilution clauses—to invest at the valuation a founder wants, but with terms that make sense for the investor. In a down market, when capital is more expensive and valuations are down, these structured deals—that is, a deal with non-standard clauses—become more common, as founders look for ways to avoid raising money at a lower price per share than your previous round (i.e., a down round).

Our aim in this piece is to arm startups with an understanding of different contract terms used to increase headline valuation, how investors think of and use those terms, and the impacts, especially on equity dilution, to consider before signing on the dotted line.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The equity-to-debt spectrum

TABLE OF CONTENTS

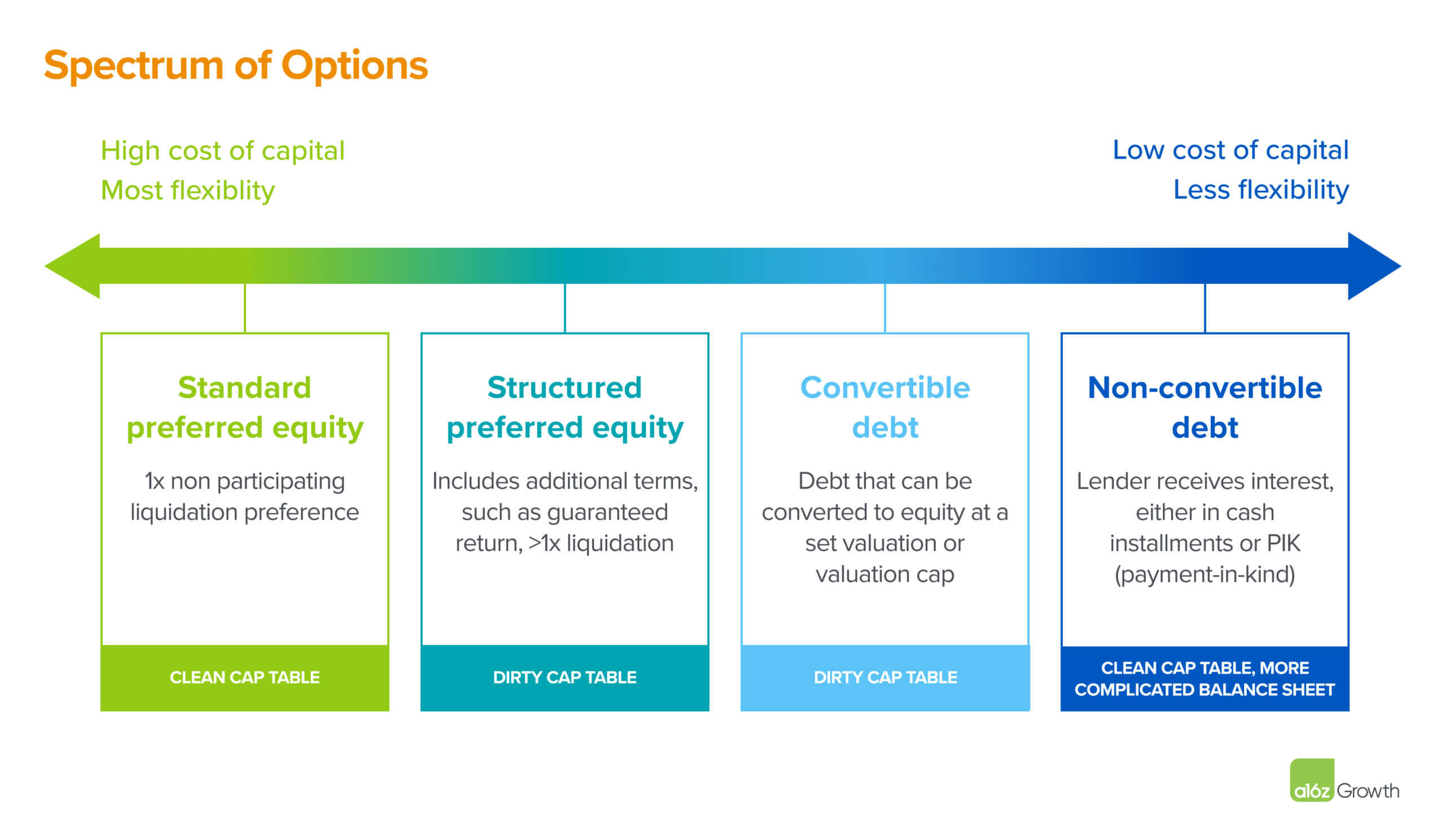

In practice, different options and terms can be combined, and in later sections, we’ll dig into both specific terms used to sweeten equity proposals and a side-by-side comparison of common scenarios. For simplicity, though, let’s look at four high level options: standard preferred equity, structured preferred equity, convertible debt, and non-convertible debt. These options can roughly be thought of on a spectrum that trades cost of capital and dilution for flexibility.

On the equity end of the spectrum, standard preferred equity, rather than common stock, is the most common equity structure for private institutional investors. When someone gets a “clean term sheet,” that usually means standard preferred equity with a 1x non-participating liquidation preference (more on liquidation preferences in the next section). On the other end of the spectrum, non-convertible debt caps the lender’s return at the interest rate, so might make for a “clean term sheet,” albeit a more complicated balance sheet. (You can find our guide to raising debt and debt terms here).

In the middle, structured preferred equity and convertible debt are often considered “dirty term sheets” because they add deal terms that sweeten the deal for investors, such as features to add incremental potential upside or increase the guaranteed minimum return.

Economic deal sweeteners

Structured clauses and deals, despite being called “dirty,” aren’t innately good or bad, and we aren’t here to tell founders what the right terms are for their business. However, we do want to make sure founders understand the tradeoffs that come with a structured deal. With any term sheet—up or down—a founder is focused on the valuation. If one raises the same amount of capital on the same terms, but at a higher price, the financing is less dilutive to existing shareholders.

While structure can happen in up rounds, it is more commonly seen as a means of minimizing decreased valuation from the prior round. For example, a founder might have the choice of accepting a “clean” term sheet at a 40% discount or accepting a structured flat round. Most employees, customers, and partners will not know about the structure and a flat round sounds better than a 40% down round.

In reality, the best funding option comes from striking the right balance of valuation and dilution to align incentives among your investors and board, the founders, and the employees. Here, we’ll dig into some of the most common sweeteners that are used to increase headline valuation and how they impact dilution and stakeholder alignment.

Warrants

What it is: Warrants are one of the most common ways investors and founders structure contracts to turn a down round into a flat round. Warrants (or options) give the investor the right, but not the obligation, to purchase a predetermined number of shares of the company at a predetermined exercise price before the expiration date, which can range from a few months to a decade. That exercise price can be as little as one cent (or even fractions of a cent), also known as a penny warrant, or issued at the standing valuation.

Why it matters: The exercise price is the central lever used to increase valuation, but the lower the warrant exercise price, the more potential dilution. Penny warrants, in particular, are essentially free incremental shares in the company so they bring down the “real” price of the round.

Secondary financing

What it is: In a secondary financing, investors purchase stock from existing shareholders. This is in contrast to a primary financing, in which a company issues new stock in exchange for cash on the company’s balance sheet. Investors may purchase preferred shares in a primary financing at a high valuation while also purchasing secondary equity (often common stock without protections) from a prior investor at a lower price.

Why it matters: Purchasing discounted secondary stock lowers the average purchase price for the investor. Typically, lower priced secondary is blended with primary to get a lower effective price for investors. Since the new primary equity is issued at a higher price and existing stock is sold at a lower price, this allows for a higher headline valuation with minimal dilution. However, secondary comes with fewer protections for the investor, and depending on who the seller is, can be interpreted as a negative signal. For example, if the founders are selling shares in a secondary transaction, they are reducing their own ownership at a discount to the headline valuation price.

At times, investor demand may be relatively fixed such that any invested capital toward secondary sales reduces the amount available for primary. As such, for companies with downstream capital needs, they may prefer to prioritize primary over secondary.

Conversion price

What it is: The price at which convertible debt can be turned into equity. Essentially, it’s the strike price for a debt lender. The conversion price can be a valuation cap, a discount to the next preferred financing round, or benchmarked to an IPO (e.g., debt converts at 20% discount to the IPO price).

Why it matters: Convertible debt allows lenders to participate in the upside of the company while getting paid back (with interest), like debt in a less optimistic scenario. Founders typically want to set as high as possible a conversion price, similar to pricing a round, to minimize dilution.

Anti-dilution clauses

What it is: Anti-dilution clauses, such as an IPO ratchet, protect investors from pricing the current round too high by granting more shares to investors if a future round or IPO is priced below a predetermined level.

Why it matters: For investors, anti-dilution provides more safety around a higher headline valuation. If the valuation later declines, particularly at IPO, they will be given more shares to make up some or all of the difference. If valuation declines, this translates to (an often significant) dilution for founders and other unprotected shareholders. While nearly all equity financings have price-based anti-dilution protection, “ratchet” protection—where investors are made entirely whole from a future down round or IPO—are usually only found in structured deals.

Liquidation preference

What it is: Liquidation preference refers to who gets paid back first, and how much, in the event of liquidation. Seniority ranks the order in which investors are paid back, with the most senior paid first—making them the most secure.

Multiples refer to what multiple of the original investment must be paid before less senior investors are paid. Typically, investors take a 1x liquidation multiple, so they get their money back before common equity shareholders get anything. However, a liquidation preference multiple can be greater or less than 1x.

Liquidation preference can also be participating or non-participating. A non-participating liquidation preference means the investor gets the greater of the underlying liquidation preference or the value of such investor’s pro rata ownership of the company. A participating liquidation preference means the investor gets the liquidation preference and the value of its pro rata ownership of the company, if any, after its liquidation preference is paid.

For example, assume a company was worth $1B and had an investor with a 1x participating liquidity preference who invested $100M and owns 20% of the shares. At sale, the investor would first receive $100M, leaving $900M. Then, they would receive 20% of the $900M according to their pro-rata ownership—getting $280M total, or 28%, of the total equity value.

Why it matters: Liquidation preference is most relevant in a downside scenario. If the company exits at a higher price per share than the per share price an investor paid for preferred equity multiplied by the liquidation preference multiple, such preferred equity converts into common stock and, if non-participating, has no effect on the proceeds received by the holders of common stock. If, however, the company exits at a lower price per share, or in the unfortunate case of bankruptcy, investors get their investment back (or a portion thereof) before common shareholders receive any proceeds.

The majority of “clean” financings stipulate that all preferred investors are paid their liquidation preference on an equal basis (often called pari passu in term sheets and legal documents). Some structured investors push to have a senior liquidation preference, where the latest investors get paid their liquidation preference before existing investors.

A 1x liquidation preference is standard for investors and protects invested capital by guaranteeing a return for investors and preventing startup teams from doing a dividend on the investor’s cash on a pro rata ownership basis and running away with the investor money. However, in a down market when investors become more risk averse, it’s more common to see liquidation preferences at higher multiples (e.g., 1.25–2.0x, but could be higher).

While less common than adjusting the liquidation multiple, a participating liquidation preference is a significant economic sweetener, though it does reduce the distribution pool in the cap table for everyone else and is perceived to be “double dipping.” For that reason, companies often negotiate the participation feature to fall away after a certain return threshold is met (e.g,. 3.0x).

PIK interest

What it is: Rather than paying cash on a quarterly or annual basis, payment-in-kind, or “PIK”, compounds the original investment of the security with all structure and protections included. These PIK payments can appear as dividends in structured equity deals, and as accruing interest in structured debt deals.

For example, a $100M note with a 10% cash interest rate would pay out $10M in interest and still have $100M in principal after one year, while a 10% PIK interest rate would pay out nothing but have $110M in principal after one year. After another year, the cash interest note would pay $10M and still have $100M in principal, but the PIK interest note would again pay nothing and have $121M in principal (i.e., 10% of $110M=$11M and $110M+$11M=$121M). Note that all features and terms of the original note would be preserved with the PIK. For example, if there was a 1.5x liquidity preference, that would apply to all $121M of the principal, not just the original $100M.

Why it matters: PIK interest means no cash outflows for the duration of the time the accruing equity or debt is outstanding, but leads to a greater number of shares, a structured equity deal, or more principal at the end of the term. This can mean more dilution or a larger cash outlay on repayment. Often, these PIK payments are compounding, so investors receive additional dividends or interest on dividends or interest paid, which can add up quite significantly.

Governance provisions

What it is: Structured transactions often carry stronger governance provisions and added blocks for investors. One of the most common governance provisions is around IPO auto-conversion, which refers to shares automatically converting into common stock at IPO. Auto-conversion is standard practice, but investors can gain incremental optionality (and leverage at the time of an IPO) by requiring a majority vote for auto-convert or leaving the possibility for a vote to block auto-conversion at IPO. Other governance provisions can add protective provisions that determine whether new investors have strong voting rights on the board composition, veto rights, etc.

Why it matters: Optionality is valuable to investors, especially since many protections in structured deals (liquidity preferences, minimum returns, the ability to get repaid as debt) expire at IPO.

Recapitalizations/cram downs/pay-to-plays

What it is: If times are very tough, investors can push for a term sheet with “recap,” “cram down,” or “pay-to-play” provisions. While structured in different ways, most involve converting the preferred shares of all existing investors into common shares at a 1:1 ratio or lower (5:1, 10:1 etc.). This wipes out all of the liquidation preferences and other rights of the existing investors, and in the case of lower conversation ratios, strongly dilutes all existing investors. The new investors then typically come in with preferred shares that are senior to those of earlier investors.

A “pay-to-play” or “pull-up” provision may also be included, where existing investors who participate in the new round at their pro rata allocation (or other standard) then get their common shares re-converted to preferred shares. These re-converted shares sometimes restore the existing investors’ rights in full, but sometimes the re-converted shares are less senior to the new investors’ shares and carry a <1x liquidation preference.

Why it matters: The “recap” or “cram down” term sheets typically happen when a company is relatively distressed. The structure allows the new investors to contribute new money that is protected, since they are now the most senior preferred, and allow the new investors to invest new money into a company with a lower liquidation preference stack (which can grow to be quite significant in later stage companies that have raised a lot of money). The “pay-to-play” term sheets can have these same effects, but have the added effect of incentivizing the company’s existing investors to continue participating in the company’s fundraising.

Hypothetical scenarios/term sheets

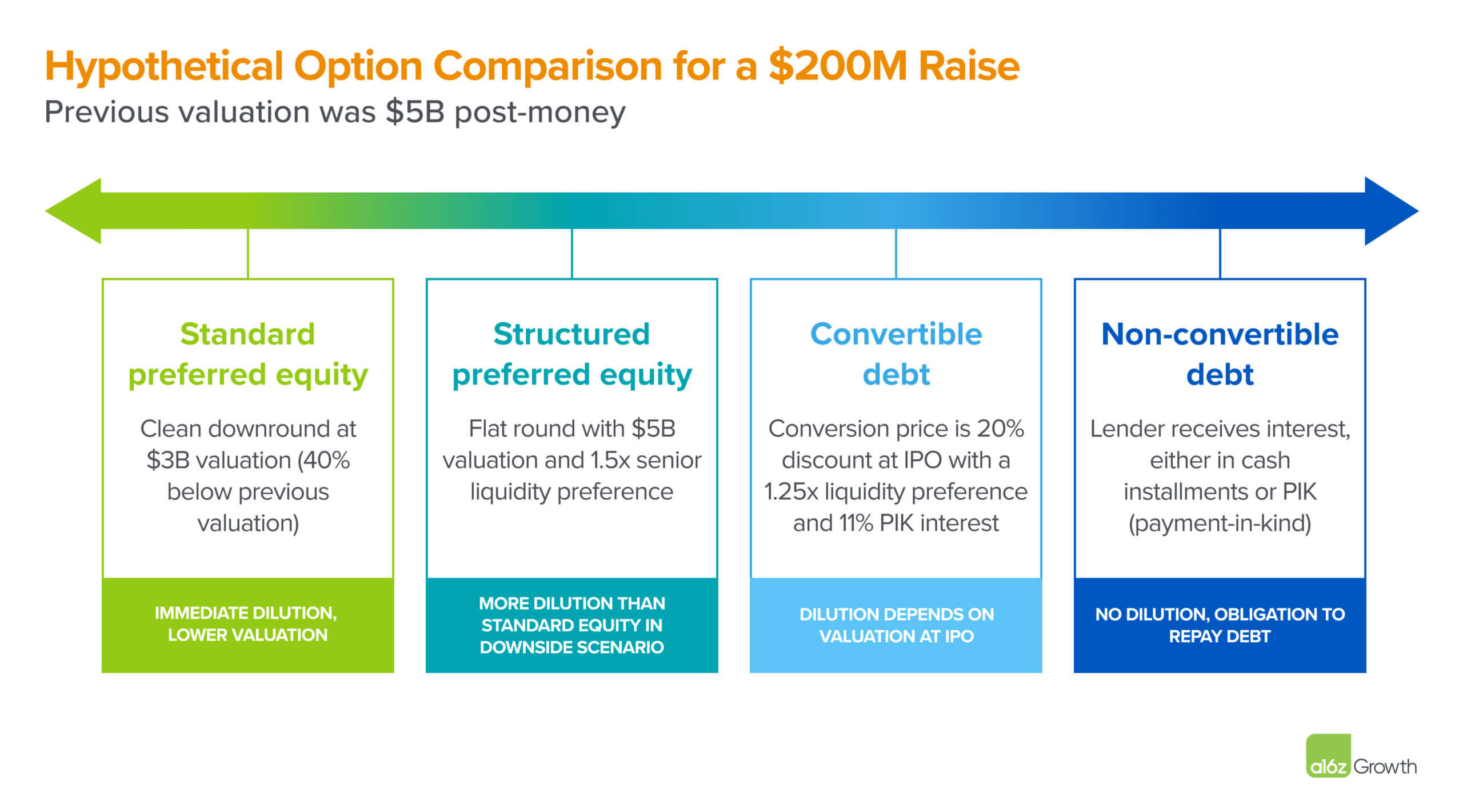

Now that we’ve laid out some of the most common structured terms, let’s look at how this plays out in different fundraising scenarios. To set up our scenarios, let’s imagine that a company last raised at a $5B post-money valuation. Since that raise, the market has become tougher, and the company is in the position of having to decide between a “clean” down round, a structured round, convertible debt, or non-convertible debt..

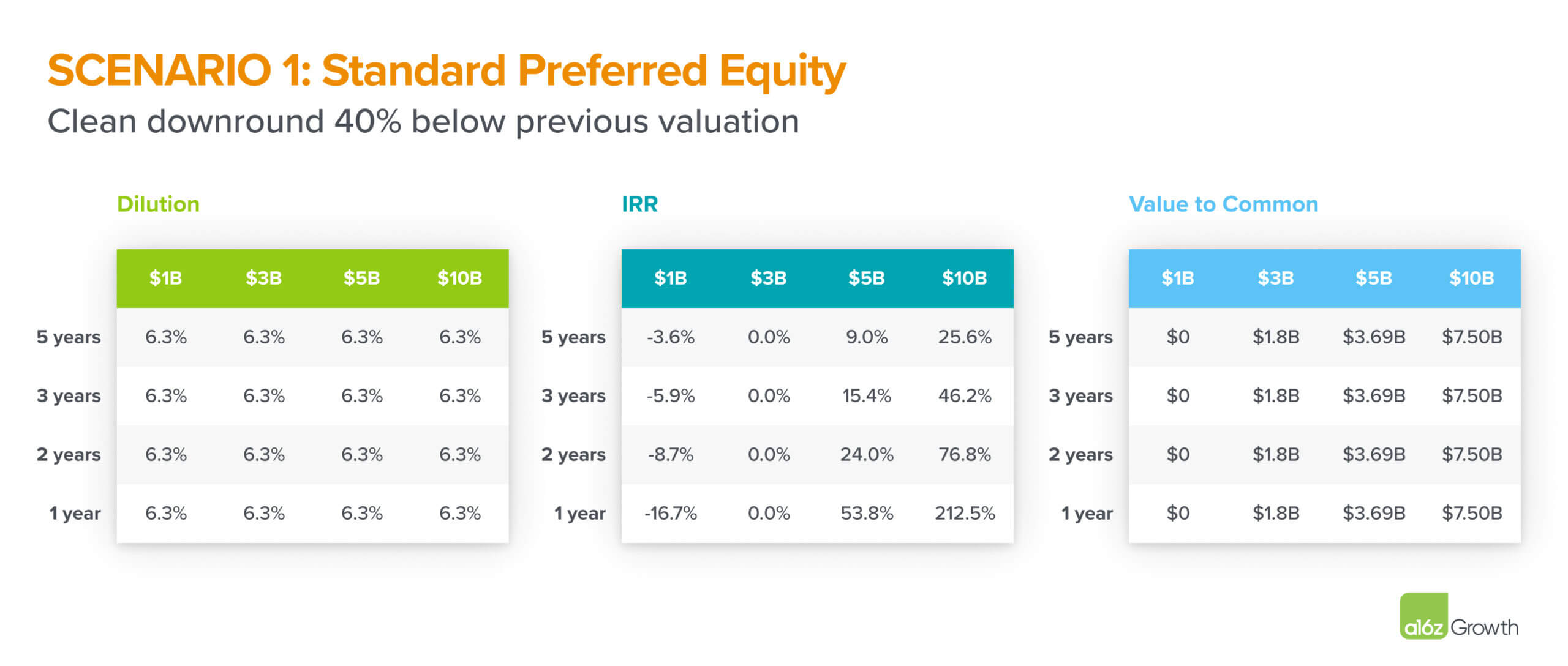

Within each scenario, we present the sensitivity tables that we would use at a16z to quantify the company’s internal rate of return (IRR), which is one way that investors evaluate potential returns and dilution. For every proposal with a given structure, we plug the model in to assess the cost of capital and dilution for expected timeframes and potential exit values.

Scenario 1: Clean down round 40% below previous valuation

Down round is a financing in which a company sells equity at a price per share that is lower than the price per share for equity issued in its prior financing. For our first scenario, the company will do a clean down round with standard preferred equity, raising $200M at a $3B pre-money valuation, or 40% below its previous valuation. The new investors now own ~6.3% of the company (not including any anti-dilution adjustments to the existing investors’ holdings that may be triggered). If the company had done a flat round at $5B pre-money, the new investors would own ~3.8% of the company.

As investors, we evaluate a down round much the same as we do an up round: we start with a blank sheet of paper rather than anchoring to a previous valuation. We assess the company—its performance, business model, market opportunity, management team—to determine the valuation we are willing to pay. Sometimes that is higher than the last round value, sometimes lower, but we try to not over-index on the last round and form our view on valuation based on our current assessment of the company’s future potential cash flow generation.

Pros: The down round keeps the cap table clean, which is particularly valuable for incentive alignment.

Cons: A down round will dilute existing equity more than a clean flat or up round, and can send a negative signal to the market. Further, a down round can impact employee morale, especially if it puts them underwater on their options.

For founders, raising a down round usually means worrying: will current employees who have seen their options and shares lose value start looking for new jobs? Will prospective employees want to join? Will customers and partners worry about our ability to provide our service? Will we have trouble raising rounds in the future if we take a down round now? These are legitimate concerns, and in a down round, you need to be aware of and prepared to address them.

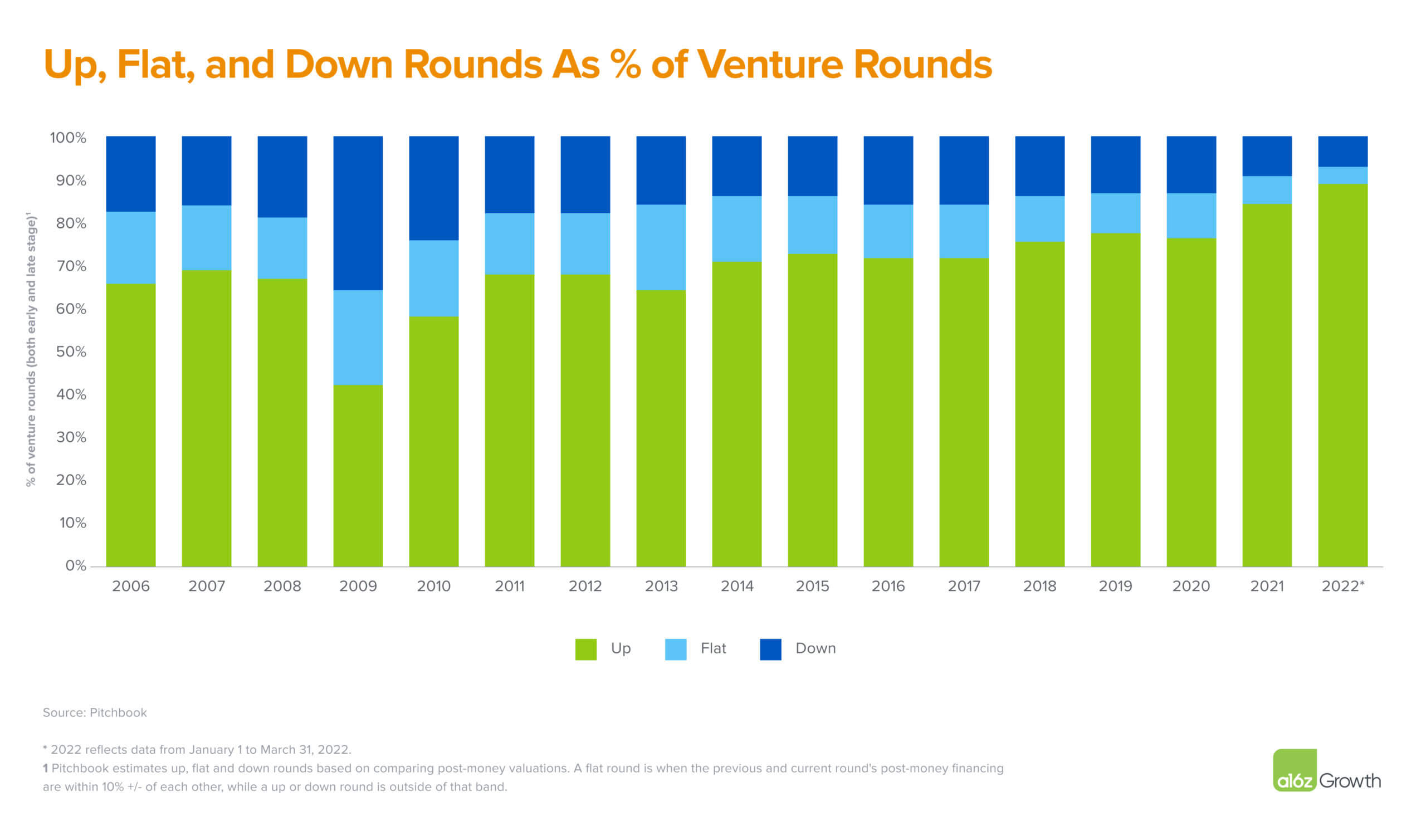

However, the reality is that down rounds are far more common than most people realize, even in good times. In fact, companies that have raised down rounds include Facebook, Square, DoorDash, and Box. From 2006 to 2020, flat and down rounds were 28% of venture financings. At the end of the Global Financial Crisis in 2009, the median VC financing was a flat round, and more than one third were down rounds.

When a company nears IPO, has more investors and employees with equity, and a clean cap table becomes more important, a down round may be the best option.

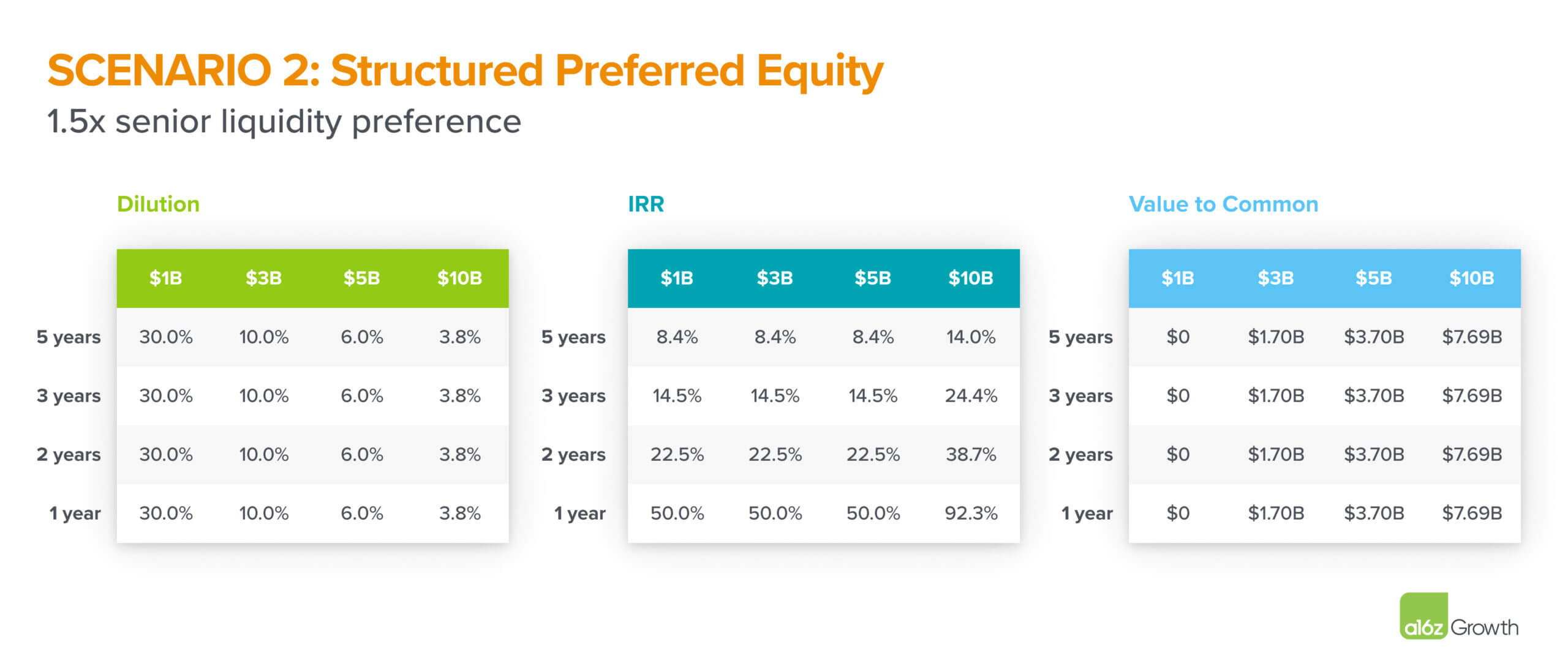

For our second scenario, the company raises $200M at a valuation of $5B, or flat with the previous valuation. The new investors will receive a 1.5x senior non-participating liquidity preference. Assuming no change to share count, the new investors now own ~3.8% of the company; the new investors are also guaranteed in M&A at least 1.5x their money before any prior investors or common equity holders share in the economics. Most typically in an IPO scenario, preferred shares would convert at 1:1, such that liquidation preference higher than 1.0x would not ensure a return, though those investors may have an IPO block or negotiated a minimum return in an IPO scenario.

Pros: This structure results in no change in headline valuation and in a strong upside scenario, and less dilution than a clean down round.

Cons: The 1.5x senior liquidity preference generally guarantees the new investor a return in all but the worst downside scenarios before investors in earlier rounds and common equity shareholders begin to participate.

Bottom Line: Structured preferred can help maintain a headline valuation with more limited dilution in the upside. However, if the company does not do as well as expected, the new investors will earn a return before old investors and common equity begin to participate.

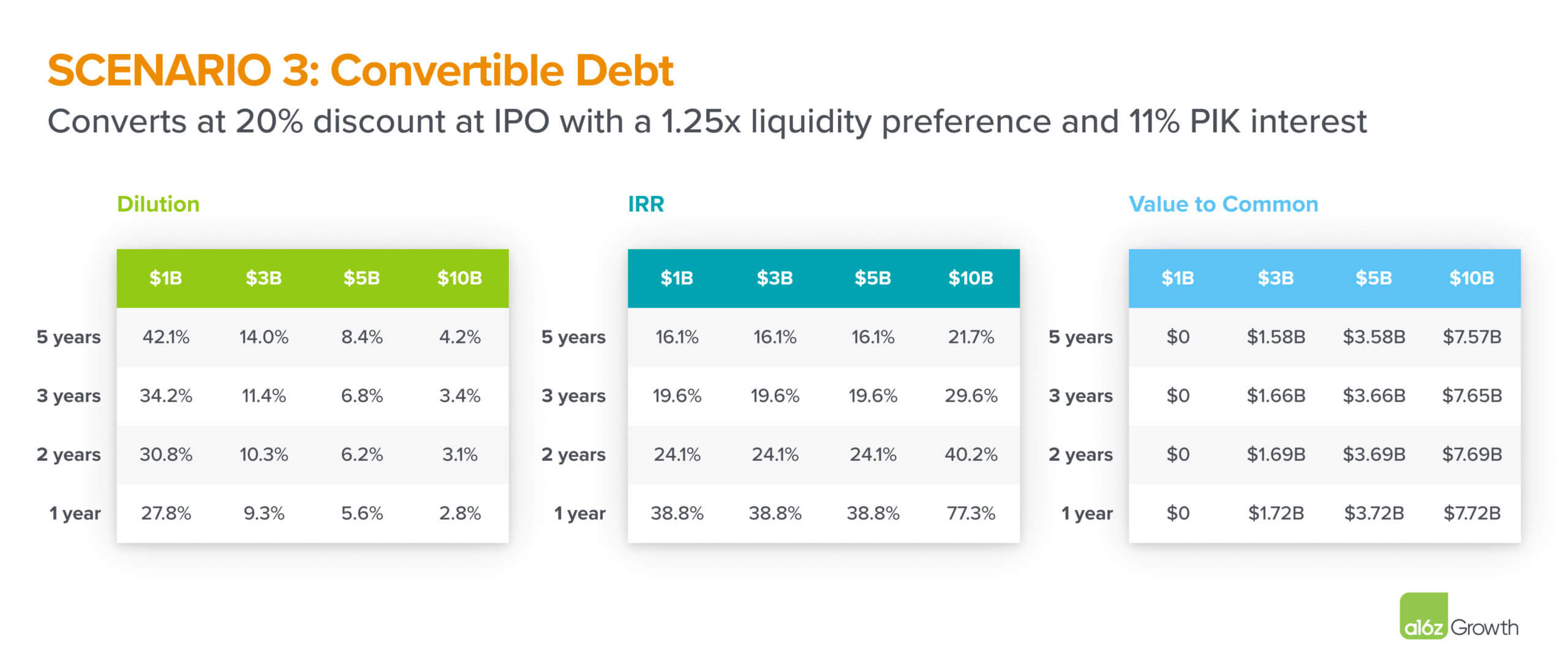

Scenario 3: $200M convertible debt that converts at a 20% discount at IPO with a 1.25x liquidity preference and 11% PIK interest

For our third scenario, the company will take a $200M convertible debt note with a conversion price of 20% discount to the IPO price, 11% PIK interest, and 1.25x senior liquidity preference. The new investors’ ownership is dependent on the IPO price and timing. As an example, if the company valuation doubles from the last round to $10B at IPO in two years, the convertible note would convert to ~2.4% of the company shares. On the other hand, if the company IPOs at $5B (flat to prior valuation), the convertible note would convert to ~4.8% of the company shares. If the company IPOs at $4B (20% less than prior valuation), the convertible note would convert to ~6.0% of the company shares.

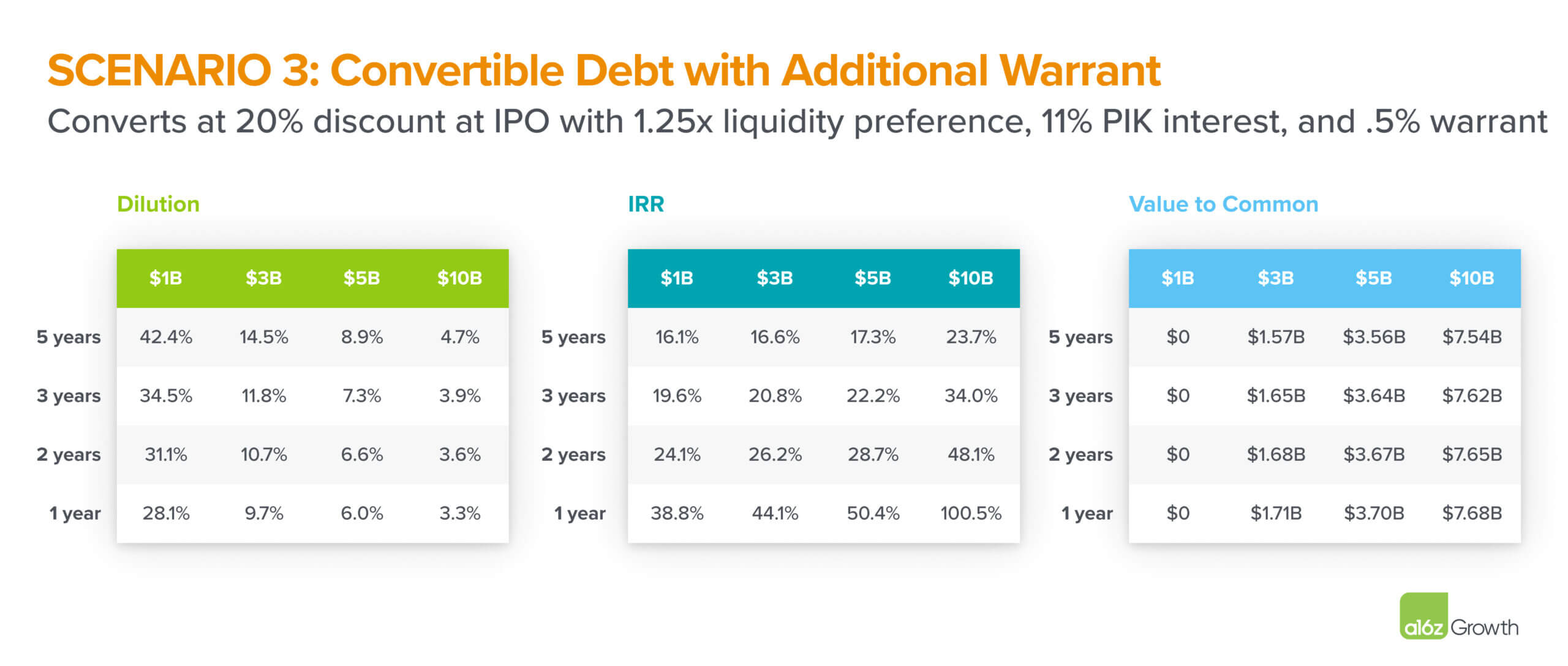

If we were to add a 0.5% warrant (calculated as 0.5% of the fully diluted shares outstanding before any convertible debt shares) to the above scenario, here’s how that would further sweeten the deal for investors.

Note since the warrant dilution is set before the convertible debt is converted, the warrants are also then diluted along with older preferred and common shares. The lower the exit equity value, the more dilutive the convertible debt is, so the warrants and existing shareholders are both more diluted.

Pros: This structure results in no change in headline valuation, and allows the exact dilution to be determined with the valuation at IPO, which can be helpful if the company is in a temporary rough patch and feels better about its prospects farther down the line at IPO.

Cons: Convertible debt is relatively high cost debt (including interest) and adds complexity to the capital structure, which can be relevant near IPO. If the value of the company increases past the mark, the convertible debt will act as equity. If the value of the company decreases, the convertible debt will act as expensive debt that has seniority to equity upon liquidity events.

Bottom Line: Convertible debt can help maintain a headline valuation and will limit dilution if the company does well compared to standard preferred. However, it introduces complexity into the cap table and can be very dilutive if the company does not do as well as expected.

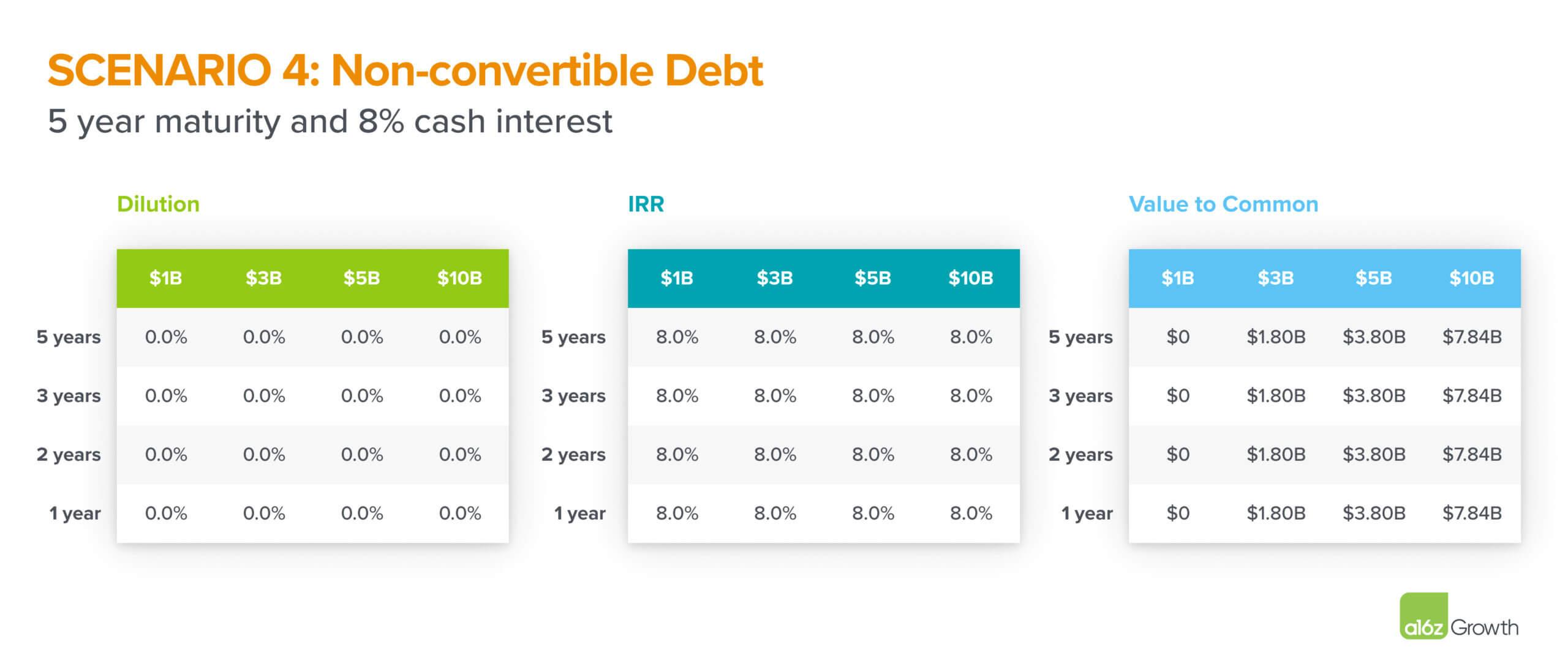

Scenario 4: $200M debt with a 5-year maturity and 8% cash interest

For our final scenario, the company takes on $200M of venture debt with an 8% cash interest rate and 5-year maturity. The company immediately pays ~$5M in fees at close (directly deducted), then must make a payment of $4M every quarter ($16M every year) for the next five years. At the end of the fifth year, the company must repay $200M. The company also has to conform to lender covenants, and submit detailed financial and other compliance reporting to the lender.

Pros: Vanilla venture debt is cheap, simple, and will keep the cap table clean.

Cons: Venture debt availability depends on the health of the company. In a downturn, venture debt may become less available, if at all. There are likely more covenants and reporting required as part of taking on venture debt, which is issued by lenders with a lower risk tolerance. Flexibility is also likely very low and the company is bound to pay cash interest on a regular basis, which will impact cash flow, as well as a bullet principal payment at the end of 5 years.

Venture debt is senior to equity so in a downside scenario, first capital distributions would go to the debtholders ahead of any equity holders.

Bottom line

Venture debt is a simple, low-cost way to continue funding the business. As the senior most piece of the capital structure, these debtholders are the first paid out. When available, venture debt is a good option for companies when the business model is understood and the company could flip to profitability based on their existing cash balance. However, venture debt will often come with stringent reporting requirements and covenants, as well as strict interest and principal payment schedules.

For founders, job #1 is to get to the next round of funding or cash flow positive, and it’s a job that gets tougher when the market turns. But if you can strike the right balance of dilution, valuation, and flexibility in your fundraising strategy, it can be a strategic advantage that doesn’t just allow you to survive lean times, but puts you in a strong position to capture market share and grow when the market comes back.

Note: returns and ownership are approximate, and calculated with simplifying assumptions such as no incremental dilution from further fundraising or effect from anti-dilution provisions. IPO valuations assume no debt and thus represent market capitalization, except in the venture debt scenario where $200M of debt is assumed.

If you’re curious to learn more about financing for startups, we recommend picking up Scott Kupor’s The Secrets of Sand Hill Road: Venture Capital and How to Get It.