Leia esse artigo em Português.

When most people think of Brazil, the country’s golden beaches, world-class soccer players, and famous Carnaval festival spring to mind. Top of mind for us, however, is Brazil’s financial regulation. Over the past decade, the government has introduced regulatory changes that have provided significant tailwinds for many fintech companies.

Financial regulation is generally a headwind for innovation. In most of the world and in most industries, regulation, compliance, and licensing are words that are associated with red tape, meddling bureaucrats, and outcomes that favor the status quo and entrenched interests. Brazil offers a refreshing counter-example of how this need not be the case. Regulatory changes have enabled increased competition that has yielded significantly better experiences for consumers and businesses, and improved financial inclusion.

Having previously expounded on the explosion of fintech activity in Latin America, here we will dive into the Brazilian Central Bank’s (BCB) methodical “pro-innovation” regulatory agenda (sometimes in partnership with other government entities), which has transformed Brazil’s staid financial industry.

In 2010, Brazil was beholden to an oligopoly of five banks, who enjoyed record profits by focusing mostly on the top of the income pyramid (with mediocre products and services). In 2022, Brazil now has hundreds of fintech startups which have increased Brazilians’ access to financial services from 57% to 86% of the population in recent years (see chart) — thus bringing 75 million Brazilians into the banking system. The fierce competition between these new companies raised the bar across the board for all banking products and services. As the government continues to push new regulations, we are excited for the growth of both current and future generations of fintech companies.

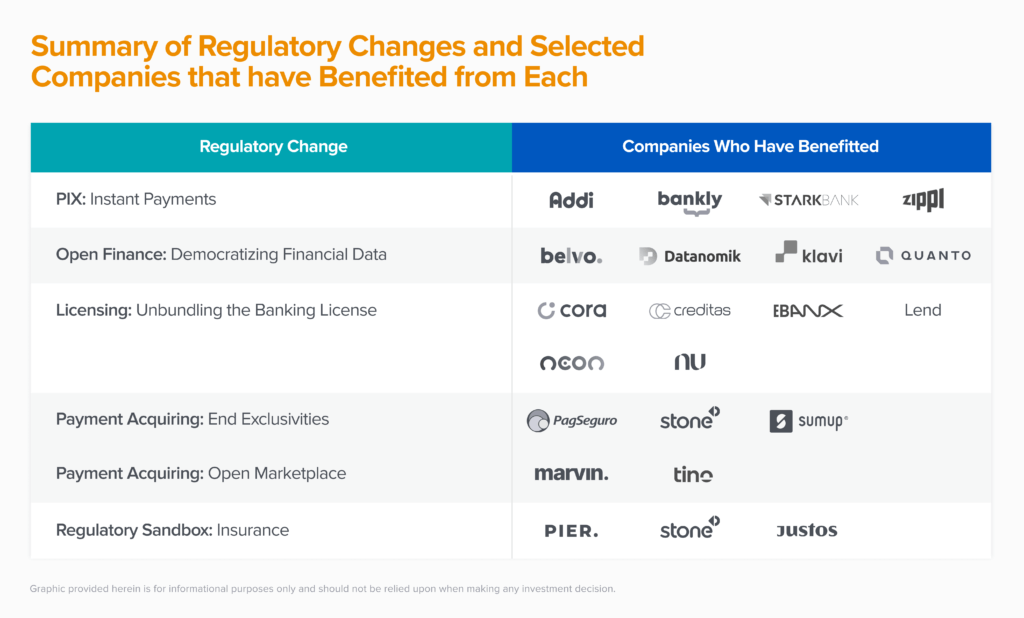

We will dive into five of these regulatory changes that have propelled this fintech explosion—instant payments, open finance, licensing, payment acquiring, and insurance—and the companies that have been created as a result.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pix: Instant payments

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Until 2020, the majority of consumers in Brazil used cash, expensive wires, or an antiquated Boleto system that takes an average of 2-3 business days to settle.

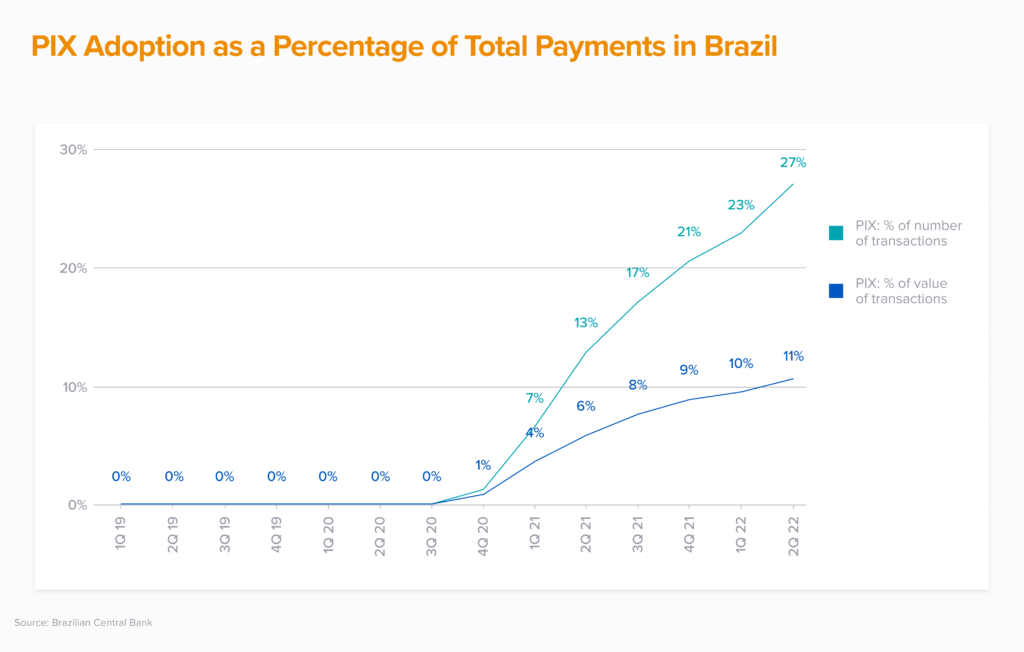

In November 2020, the BCB launched the instant payment system PIX, a real-time rail that provides free (for consumers, businesses may be charged) and instant money transfers and settlement between accounts at participating institutions. In less than two years, PIX has been used by 139 million users (roughly 75% of the population). By 2Q22, PIX accounted for 27% of all payment transactions and a 11% share of payment value in Brazil (see chart). It is not uncommon today to use PIX to pay for items as small as a beach chair rental or a coconut water on those famed golden beaches.

Contrast this to the United States, where FedNow has been coming for years (i.e., definitively not “now”).

The BCB made several strategically smart choices as we have written more about:

- PIX is free for consumers while businesses may be charged a fee.

- PIX has a standardized consumer experience and is real time and 24/7 (a significant advantage over both boletos and Brazil’s equivalent of ACH, which is real time but only during working hours).

- Participation is required by all financial institutions with more than 500k consumers.

- Non-financial institutions can participate through an “indirect participant” license, which allows for rapid adoption by fintech companies.

Further, the BCB plans to continue adding functionalities such as “Scheduled PIX” to replace scheduled payments, “PIX Withdraw” to enable withdrawals, and “Guaranteed PIX” to create a payment option that is similar in functionality to a business credit card. Finally, “International PIX” will enable users to transfer their assets to bank accounts in foreign countries using PIX.

The successful adoption of PIX is accelerated by companies like ADDI who leverage the PIX network for their Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) solution. While the consumer and business benefits of PIX are immense, new networks always come with additional challenges — and hence opportunities — for new companies. For example, instant payments are irreversible, which increases the importance of Know Your Customer (KYC)/Know Your Business (KYB) and fraud controls; this is an opportunity for a startup with an intelligent risk and fraud model and compliance expertise.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Open Finance: Democratizing financial data

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Instant payments are a huge step toward providing financial choice and removing the regressive tax that is felt most often by the consumers who need their cash the fastest. The next stronghold incumbents have over customers is the non-portability of data. User ownership of data needs no exposition in today’s world, yet implementing systems to allow secure execution has always been a challenge.

In 2021, the BCB began implementing Open Finance, a system aimed at giving consumers better control of their own data. As we have seen in the U.S. and the U.K., allowing consumers to grant third-party apps access to their data has been one of the biggest drivers of competition in the financial markets and hence consumer choice. For example, Venmo was able to build a large business in peer-to-peer payments by leveraging Plaid to allow users to connect their bank accounts.

The launch of Open Finance followed a tech-forward approach of launch rapidly and iterate. It uses four phases, rather than a typically monolithic and slow roll-out. The first phase required participating institutions to share standardized information on products and services like deposits, savings, and credit cards. The second phase enabled customers to share their data with applications of their choice. This has allowed companies like Datanomik to allow companies to view and reconcile payments from multiple business bank accounts, and Belvo to allow consumers to provide access to their banking data to get underwritten more quickly for a loan. Phase three, which began in 2022, focuses on launching products on top of open banking. For instance, a third-party app, if appropriately licensed, could initiate a payment directly from a consumers’ bank account without the consumer needing to leave the app, or worse, need to be present at the bank branch! Phase four, expected next year, will expand the data-sharing scope to include foreign exchange, insurance, and more.

This access to data opens the potential for new use cases and a plethora of applications soon to be created.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Licensing: Unbundling the banking license

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The availability of real-time payments and Open Finance dramatically opens up new use cases and opportunities for new companies. The Brazilian Central Bank knows that this innovation needs to be managed responsibly, with guardrails and risk controls. In the past, an aspiring financial institution would have to apply for a banking license, which would take years and large amounts of capital. The BCB’s solution today is to create more targeted and tiered licensing schemes to allow companies to operate within certain scopes much more quickly.

In 2013, the government released a new regulatory framework to clarify the compliance rules for Payment Institutions (IPs):

- Postpaid instrument issuers – i.e., non-financial institutions that issue postpaid accounts like credit cards

- Electronic money issuers – i.e., non-financial institutions that manage prepaid accounts like food vouchers

- Payment acquirers – i.e., non-financial institutions that help companies accept payments

These more narrow licenses allowed startups to offer customers financial products within these categories without having to comply with the one-size-fits-all regulatory requirements of a full financial institution (i.e., essentially becoming a bank). The late 2013 change shook up Brazil’s payments industry and benefited companies like Nubank, Ebanx, Neon, MercadoPago, Cielo, Rede, and Stone.

In 2018, to open up the credit market, two new types of licenses were created: Direct Credit Institution (SCD) and Peer-to-Peer Institution (SEP). These licenses enabled startups to operate directly in the credit market instead of having to partner with traditional financial institutions. SCD licenses, the broader and more used of the two, allow fintechs to provide credit by issuing loans and to purchase credit receivables through online channels using their own capital. Those with SCD licenses can also sell credit analysis and collection services to third parties, act as an insurance broker, and issue electronic money. Companies like Lend were able to get licensed more quickly in this way. They now use their “lending as a service” platform to support software companies who want to issue loans to their customers but don’t want to get licensed or build lending operations.

Further in 2020, the government expanded their IP framework to include payment initiators, institutions that allow users to initiate a payment without leaving their purchase environment (e.g., WhatsApp Pay). This allows for significantly improved user experiences for payments within applications. Now with real-time rails, Open Finance, and faster licensing, a new software platform to help homeowners manage their homes, for instance, could allow a homeowner to login to initiate an instant payment to a contractor without ever leaving the app, and the payment would settle instantly.

As every company is becoming a fintech company, this creates opportunities for consumer and enterprise companies alike to more seamlessly integrate payments into their services.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Payment acquiring: Ending exclusivities, opening receivables marketplace

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Prior to 2010, the payment processor Cielo, owned by Bradesco and Banco do Brasil, had an exclusive deal with Visa. The rival payment processor Rede, owned by Itaú, had an exclusive deal with Mastercard. As a result, Brazilian merchants had to own or rent at least two point-of-sale (POS) machines: one from Cielo to process Visa transactions, and one from Rede to process Mastercard transactions. Merchants had no other options and no negotiating power.

The BCB ended this duopoly in 2010, enabling competition and giving merchants bargaining power. Merchants could use Cielo’s, Rede’s, or any other entrant’s POS machine to process credit card transactions from both Visa or Mastercard.

The BCB moved to further eliminate other exclusivities between acquirers and credit card networks in 2017 — namely those between Rede and credit card network Hipercard (which share a shareholder in Itaú), and Cielo and credit card network Elo (which share Banco do Brasil SA and Banco Bradesco SA as shareholders). The sum of all these changes enabled new entrants like Stone, PagSeguro, and SumUp Brasil.

While this regulatory change solved a lot of issues, it did not address the cash-flow challenges merchants faced. In Brazil, the concept of buy now, pay later (BNPL) is nothing new. Brazilians have been paying in installments for decades — first with checkbooks called crediários, and now with credit cards, and many Brazilians prefer to pay for their purchases this way. But while customers love paying credit card bills in installments, merchants find this practice challenging for their cash flow, as they end up accumulating credit card receivables that won’t be fully paid for up to 12 months.

For example, say a customer chooses to buy a R$1,000 product in June with a four-month installment plan. Assuming a 3% merchant discount rate (MDR), charged by the acquirer to the merchant, the merchant would receive R$970/4 or R$242.5 in July, August, September, and October since payments start 30 days after a credit card transaction. Most merchants cannot afford to float this amount of cash for months (in this case, the merchant would not be fully paid until October). So, in order to receive as much cash as possible upfront, the merchant pays the acquirer a large discount fee that can often reach double digits per month. If we take a 5% discount rate as an example, the merchant would then receive the first installment discounted by 5%, the second one by 10%, the third one by 15%, and the fourth by 20%, resulting in only R$849 — a pricey ~15% loss! Acquirers have been able to drive such lopsided terms because of limited competition and still low bargaining power on the part of many merchants. Factor in that the customer credit risk is on the issuer, and you can see how these cash advances are almost pure profit for acquirers.

Before 2021, merchants could only get these receivable advance deals from their acquirer since they were the only party with access to the balances. There was no competitive marketplace. To drive competition in the receivables market, the BCB created the concept of registration entities. Acquirers now need to register all of their merchants’ receivables into these entities and buyers have an opportunity to bid on the discount rate offers for these receivables. The new regulation also opened up broader opportunities for entrepreneurs, such as offering credit using receivables as collateral. Companies like Tino and Marvin have used this new opportunity to scale, and we expect to see many more innovative startups in this space.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Regulatory sandboxes: Insurance

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In 2020, the Ministry of Economy, in partnership with the BCB, the Comissão de Valores Mobiliários (CVM, the securities and exchange commission), and the Superintendência de Seguros Privados (SUSEP, the body that regulates insurance) created three sandbox programs. The sandbox created in partnership with SUSEP allowed companies to test new insurance solutions in a supervised environment. Initially, they selected one cohort of 11 companies to participate in the program. Companies had 36 months to then test their product in the market. Ten of the first 11 companies, including Pier and Stone, received permanent authorization to offer their product. SUSEP, which runs the sandbox program, has chosen a second cohort of 21 new companies to participate in the sandbox. Companies like Justos have leveraged the sandbox to get fairer car insurance to market.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Brazil’s fintech future

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Brazil’s fintech future is bright. A generation of iconic companies have proven what’s possible, and a next generation of entrepreneurs is already building on their success. Brazil’s strategic regulatory changes provide a strong “why now” tailwind: scaling and broadening instant payments, democratizing financial data, unbundling the banking license, breaking up concentrated links in the acquiring value chain, and creating safe testing environments for new products via initiatives like the regulatory sandbox. The continued modernization of the regulatory regime and the eagerness of Brazilian entrepreneurs to create compelling products and services for consumers and businesses, make Brazil an exciting place to be. If you’re building the next large fintech company, based on these trends or new expected ones, we would love to connect.

-

Angela Strange is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on financial services, insurance, and B2B software (with AI).

-

Flora Oliveira was previously Chief of Staff to the CEO at Loft. Before that, she was an investor focusing on the financial services, B2B, and consumer spaces at Advent International in Brazil.

- Fintech Fuels Global Payments

- Software Transcends Borders—Why Not Money?

- More Countries, More Problems: Selling AI Products Around the World is Still Too Hard

- The Company of the Future is Default Global

- Every Company Will Be a Fintech Company

- Paradise FedNow? How the 2023 Payments Network Will Improve Real-Time Payments (September Fintech Newsletter)