Former U.S. Army Green Beret and a16z crypto deal partner, Alex Pruden served in Iraq, Afghanistan, Kuwait, and Turkey. During this time, he saw first-hand that underlying the Syrian refugee crisis, the rise of radical extremism, and other global conflicts was a lack of trusted institutions. As a result, in times of crisis, the basics of modern life – such as identity documents and bank accounts – could vanish overnight and ensnare ordinary citizens in a vicious cycle of war and poverty.

In this talk from the a16z Summit this year, Alex shares his unlikely journey from the Middle East to Silicon Valley, and why he believes that crypto and blockchain can make a difference in the most intractable global challenges and crises.

Video Highlights

- Why Alex joined the US Army [1:20]

- Alex’s time in Afghanistan developing the local economy as part of a counterinsurgency [2:20]

- Alex’s time in Iraq and what he learned about aid relief and why ISIS was able to take over [5:19]

- Alex’s time in Southern Turkey training Syrian rebels [7:47]

- The story of one Syrian refugee and what it reveals about the Syrian Refugee Crisis [8:45 ]

- Unpacking the lack of trusted institutions as a root cause of global conflict [11:33]

- Discovering the bitcoin whitepaper and why it matters [12:41]

- The 3 features of blockchain that could help us address global conflicts [13:11]

- Russia, Venezuela, and other global hotspots where blockchain could help [15:00]

- Alex’s career pivot into blockchain & crypto technologies [16:01]

Transcript

I spent 10 years of my life in the U.S. Military. And some of my colleagues from that time sometimes ask me, “Alex, how did you go from fighting in the global war on terror to investing in blockchain and cryptocurrencies? How did you go from Baghdad to bitcoin?”

And so, today I want to talk to you all about blockchain and cryptocurrencies – not so much about what they are, but about why I believe they’re important, about how I learned over the course of my three deployments to the Middle East that this is a technological innovation that can help address some of the underlying economic issues that often lead to war and conflict.

But let’s start at the beginning. I want to take you to my hometown of Tucson, Arizona, where I grew up. And I was still in high school when the 9/11 attacks happened, and that was the day that actually changed the course of my life, because it was on that day that I made the decision to join the U.S. Army.

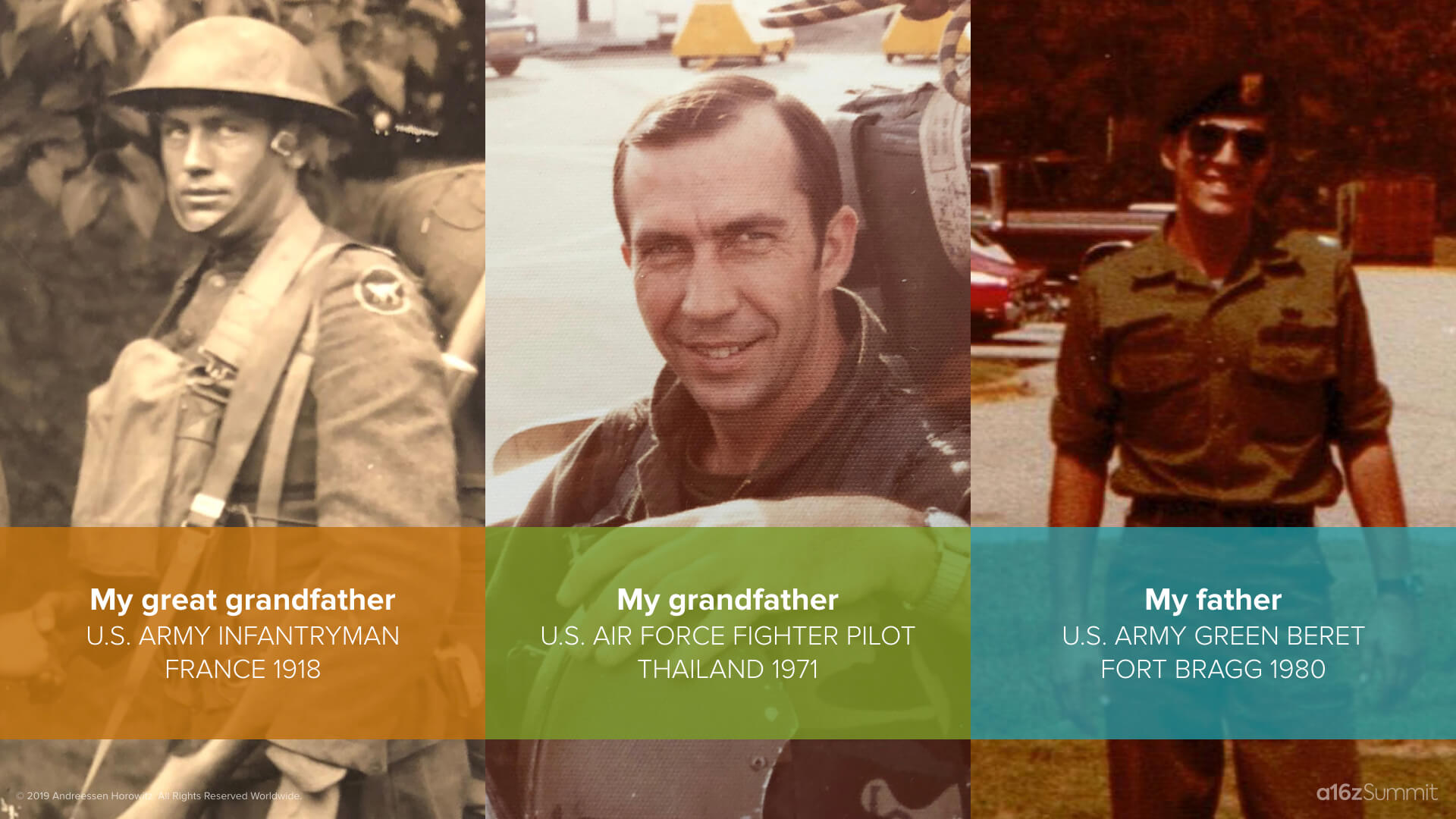

In fact, four generations before me had all served in the military. My great-grandfather volunteered to fight in France in World War I over 100 years ago now. Grandfather flew two tours in Vietnam as a fighter pilot. And my father was a U.S. Army Green Beret in the 1980s.

And so, I applied and was accepted to the United States Military Academy at West Point, where I spent four years. At the end of those four years, having earned my bachelor’s degree, I also earned my commission in the United States Army. And this was the day that I picked up the mantle for my generation. I was now the fifth generation to serve in the military, and I was taking part in what I viewed as the defining struggle of my generation, which was the global war on terror.

This is my grandfather on the left, father on the right, pinning on my lieutenant bars, my first day of service.

Shortly after, about a year later, I find myself in the Middle East in Afghanistan, and it was notable not only for its physical beauty, but for the abject poverty under which the people there lived.

Over the course of that year, my soldiers and I were in over 200 firefights. We experienced ambushes, IEDs, where seven of them were actually wounded. But for all the intensity of the combat, the centerpiece of our strategy was actually not fighting, because we were waging a counterinsurgency. And in a counterinsurgency, the key terrain is the hearts and minds of the people. And the insurgents take advantage of and ride a wave of social and economic grievances, often legitimate.

If we were to win, we had to address those grievances. And so, for as much time as we’ve spent doing combat patrols, we spent even more time trying to develop the local economy. In particular, we wanted to improve the lot of one group of people, which were the farmers that lived there in this province where we were. Afghanistan, or at least this area, was an agrarian economy. It consisted of subsistence farming, where a single failed harvest could result in devastation for not just a single family, but for an entire community.

We wanted to address that problem. And so an idea we came up with for our program to run was called crop diversification. For crop diversification, we would subsidize farmers to essentially diversify the crops they grew year over year. And that meant less frequent crop failures because more healthy soil. It meant less intense effects for any family or the overall community. And it also put money in the farmers’ pockets and discouraged them from having to turn to the Taliban to make ends meet.

For as much time as we’ve spent doing combat patrols, we spent even more time trying to develop the local economy.

We spent hours and hours, walking through fields in the area where we were in, cataloging where they were and trying to figure out essentially who owned what field so we could pay those farmers. But we kept running into a snag, which was, “Who owned what?”

Every single time that we went back to any village or area, we got a slightly different version of events over who owned this field or who owned that field. And even when we tried to involve the village elder or the tribal chief, we still often ran into disputes. These were discrepancies that couldn’t be reconciled many times.

Every single time that we went back to any village or area, we got a slightly different version of events over who owned this field or who owned that field.

Unlike in the United States or in Europe or in some developed country, there was no land registry office that we could go to. There was no place where we could go to pull a deed to find out who legally owned what property.

So, this lack of a canonical record of who owned what hindered our efforts to complete this program of crop diversification. In fact, it hindered everything that we did for economic development. And after the end of that year, my unit actually had to withdraw from that part of Afghanistan.

That experience working with the Afghans to help build their country inspired the next step in my career, which was to join U.S. Army Special Forces – colloquially known as the Green Berets – and wear the hat of diplomat, aid worker, and soldier as the situation requires, working by, with, and through host nation governments to help stop conflicts before they start.

So, shortly after my graduation from my training, I ended up back in the Middle East, this time in Iraq. And we were sent there because in 2014, a terrorist group, known as ISIS, had just emerged from the shadows sweeping through Iraq. They’d conquered the entire northern third of the country, including the second largest city of Mosul. And as we were flying over there, my team and I on the military aircraft, we were asking ourselves, “How is it possible that a ragtag band of terrorists in pickup trucks armed with small arms was able to defeat a 30,000-man Iraqi armored division equipped with the latest U.S.-built tanks?”

We were asking ourselves, “How is it possible that a ragtag band of terrorists in pickup trucks armed with small arms was able to defeat a 30,000-man Iraqi armored division equipped with the latest U.S.-built tanks?”

When we got there and started talking to some of the survivors, we learned that actually none of those tanks had fuel when ISIS arrived because most of the fuel had been sold on the black market. The 30,000 soldiers that were supposed to be defending Mosul, only 15,000 of them were actually physically present. The other 15,000 were just ghost soldiers with the commanders collecting their paychecks. And the weapons that the U.S. Army had supplied that unit, the majority of them ended up in the hands of personal sectarian militia. So, when ISIS came to Mosul, the Iraqi armored unit and the Iraqi army in general that was supposed to defend it was largely a paper tiger.

When ISIS came to Mosul, the Iraqi armored unit and the Iraqi army in general that was supposed to defend it was largely a paper tiger.

And this had devastating consequences for the people, not only of Mosul, but of northern Iraq in general. I want to highlight one group, in particular, the Yazidi people, which are an ethnic minority that have inhabited the northern part of Iraq for millennia. They were devastated when ISIS came to their ancestral home of Sinjar.

The Yazidi people, which are an ethnic minority that have inhabited the northern part of Iraq for millennia, were devastated when ISIS came to their ancestral home of Sinjar.

Tens of thousands of them were forced to flee and become refugees behind the lines in northern Iraqi Kurdistan. And the thousands that couldn’t escape suffered horrible fates at the hands of ISIS. And those that survived, women and children, were enslaved and sent to Syria for the terrorist group.

The problem, in this case, was not that there was no system of record keeping. U.S. aid to the Iraqi army, there was a system of record to keep track of what went where. The problem was it was just so hopelessly corrupt as to be completely untrustworthy.

Despite billions of dollars of aid and eight years of effort, my team, the U.S. Army, and coalition forces had to start from square one. In fact, it took two more years and billions more dollars to ultimately defeat ISIS in northern Iraq, to win a war that we thought we had already won.

It took two more years and billions more dollars to ultimately defeat ISIS in northern Iraq, to win a war that we thought we had already won.

Because of that experience, my team was then sent to another Middle Eastern flashpoint, this time, Southern Turkey, where we were training Syrian rebels. As many of you know, Syria at the time was in the middle of a brutal civil war. And these rebels, in particular, were fighting a two-front war. They were facing ISIS on one side and the Syrian regime on the other.

And for all the brutality that I witnessed in Afghanistan at the hands of the Taliban, that ISIS had perpetrated in Iraq, the scale of devastation wreaked by the Syrian regime was something that was absolutely breathtaking to me in terms of its horror.

This is some people who are leaving their neighborhood in central Damascus after years of siege.

This is some people who are leaving their neighborhood in central Damascus after years of siege. Many of them are malnourished to the point of starvation because the government had cut off all access there. I look at these people and I think to myself, except for the fact that I happen to be born in the United States, but for the circumstances that I found myself in, I could have been one of those faces. Those people could have been family members, friends.

And I want to tell you about one person in particular, who for reasons relating to his personal safety, I’m not going to use his real name, but let’s call him Dr. Hussein. Dr. Hussein grew up in a city in northern Syria called Aleppo, which before 2011 looked like this.

Dr. Hussein grew up in a city in northern Syria called Aleppo, which before 2011 looked like this.

Dr. Hussein started practicing medicine, got married, had children. The Syrian civil war broke out in 2011. Dr. Hussein was never a political man and tried his best to stay kind of out of the way and neutral. But increasingly, years passed, and the city of Aleppo went from looking like what you see here to this.

Years passed, and the city of Aleppo went to looking like this. The war was increasingly coming to Dr. Hussein’s doorstep.

The war was increasingly coming to Dr. Hussein’s doorstep. One day, he goes to his bank to pull out his paycheck, and for some reason, finds out that his account is frozen. He makes a few calls, asks a few questions to the people he knows who work in the government, and he finds out that his account has been frozen because he has now been declared a suspected rebel sympathizer. Whether it was because he just happened to live behind the rebel-held area of Aleppo or because he had treated someone who potentially had rebel or separatist sympathies, he had been marked and therefore was terrified because this meant that him and his family were in danger.

So, he rushes home as quickly as he can, packs his car, his wife, his kids, and they all drive north to the Turkish border. On their way, they’re stopped at a Syrian army checkpoint. The soldiers start questioning him. Although he’s terrified, he manages to calmly convince the soldiers to let him pass. Although in order to do so, he has to give up his passport and the passports of his family. But he doesn’t have time to argue because, again, he’s fearing for his life and that’s all he’s thinking about. Gives up the passports, gets through the checkpoint, and makes it to the Turkish border, crosses the border illegally because he has no passports and then ends up in a camp like this in southern Turkey.

Dr. Hussein and his family end up in a camp like this in southern Turkey with no passports and no bank accounts.

He breathes a sigh of relief because him and his family are finally safe. But then he realizes the desperation of the situation in which he now finds himself. He has no access to his bank account, which is back in Syria. He has no identity documents, which means that he can’t get a job to support his family. He can’t send his children to school, and he can’t apply for citizenship in the country in which he now finds himself. He’s truly hit a dead end.

There are millions of people just like Dr. Hussein in camps just like this all over the Middle East.

And this isn’t just a story of one man. There are millions of people just like Dr. Hussein in camps just like this all over the Middle East. In fact, five and a half million Syrians have been forced from their homes as a result of this conflict. It’s the largest refugee crisis in modern times. It’s a third of Syria’s pre-war population. And again, I want to emphasize that these were people who played by the rules their entire lives, but when the rules changed, they were absolutely and utterly devastated.

So, I returned home from that deployment and was reflecting on that experience as well as the experiences that I had in Iraq and Afghanistan. I thought about what were the things that we were fighting against in the global war on terror – radical extremism, terrorism that ultimately led to war.

I concluded, based on what I’d seen, that many times these things had the same root cause, which is a lack of economic opportunity, which forces people to turn, out of desperation, just to make ends meet, to potentially a terrorist group or to an extremist group. And that’s what ultimately ends up causing these conflicts.

That lack of economic opportunity is at a deeper level rooted to a lack of trusted institutions in these places. In the case of Afghanistan, there just simply are no institutions. In Iraq, the institutions are hopelessly corrupt. And in Syria, those institutions that were there to serve the people actually had turned against them, and as a result, the people were suffering terrible fates.

That lack of economic opportunity is at a deeper level rooted to a lack of trusted institutions in these places. In the case of Afghanistan, there just simply are no institutions. In Iraq, the institutions are hopelessly corrupt. And in Syria, those institutions that were there to serve the people actually had turned against them.

This was on my mind right around the time I learned about bitcoin. One day I decided to kind of dig a little bit deeper, and I ended up reading the Bitcoin white paper. I was completely captivated because what I read, to me, represented an opportunity to use this technology to address some of those underlying issues that I’ve witnessed during my military career.

In particular, I want to highlight one line: “It is an electronic payment system based on cryptographic proof instead of trust to enable any two willing parties to transact directly without the need for a trusted third.”

I want to talk about some features that blockchains enable and one of them is immutability. Any record when added to the blockchain can’t be changed after the fact. This makes it ideal for a system of tracking property ownership. Applied to Afghanistan, this could have formed the foundation for a whole legal system and an economy.

Any record when added to the blockchain can’t be changed after the fact. This makes it ideal for a system of tracking property ownership. Applied to Afghanistan, this could have formed the foundation for a whole legal system and an economy.

In fact, it’s not just Afghanistan that this could help. Various national, state and county level governments are looking at actually putting records, land records, on the blockchain because it’s far cheaper and more efficient than the alternative old system.

The second feature is auditability. Any transaction posted to a public blockchain can be traced from start to finish along every intermediate step. Applied to Iraq, this means that the sender of military aid, which in this case was the U.S., would have been able to trace along the whole path that that aid took and ensure that it got to its intended recipient. If anybody tried to siphon it off along the way, it would have been far easier to tell the source of that corruption.

Any transaction posted to a public blockchain can be traced from start to finish along every intermediate step. Applied to Iraq, this means that the sender of military aid, which in this case was the U.S., would have been able to trace along the whole path that that aid took and ensure that it got to its intended recipient.

This has applications not just in corrupt countries where there are aid organizations operating. In fact, many multinational corporations are looking at using this technology to secure the integrity of their global supply chains.

And the last feature I want to talk about is liberty. What if Dr. Hussein and the millions like him had bitcoin instead of a bank account in Syria? What if they had their identity documents saved to a public blockchain instead of carrying them in their pocket? Well, they could have crossed the border and started all over again.

Liberty is not something that’s just for the people of Syria who are suffering in the refugee crisis. It is the most fundamentally American political value that I can think of. This applies to a far greater range of countries than just places in the war-torn Middle East.

What if Dr. Hussein and the millions like him had bitcoin instead of a bank account in Syria? What if they had their identity documents saved to a public blockchain instead of carrying them in their pocket? Well, they could have crossed the border and started all over again.

In Russia, where corruption between state officials and oligarchs has stymied the growth of the economy since the fall of the Berlin Wall.

In Zimbabwe, where despite a wealth of natural resources, the lack of property records and respect for property rights has prevented that economy from getting off the ground since it gained independence 50 years ago.

In Venezuela, where corrupt government officials live opulent lives, while the average person, in the time it takes them to walk from their home to the grocery store, the money in their pocket can’t even buy a gallon of milk because of a 10 million percent inflation rate.

Finally, in Haiti, despite 10 years and billions of dollars of aid to rebuild the country after the 2010 earthquake, the infrastructure is just as dilapidated, the conditions are just as squalid, and the people are just as poor as when they started.

Liberty is not something that’s just for the people of Syria who are suffering in the refugee crisis. It is the most fundamentally American political value that I can think of. This applies to a far greater range of countries than just places in the war-torn Middle East.

Because I was so excited about the potential of this technology, I decided to make it the focus of the next stage of my career. I left the military in 2017, and I had the opportunity to attend Stanford University where I got my MBA. While I was there, I just immersed myself in everything that I could that was related to blockchain and cryptocurrency – studied cryptography, studied economics, computer science, helped found the Stanford Blockchain Club.

After graduation, I ended up finding myself here at a16z investing in entrepreneurs and founders, supporting them. These are the people who believe, like me, to their bones that this is a technology that can fundamentally change the world for the better. And they’re building that future every single day.

And speaking of that future, this is my son, Oren. Just as my parents thought about how to secure peace and prosperity for my generation, so do I think about how to do the same for his. But his generation is more than just him. He represents the sons and daughters of my friends who never came back from Afghanistan or Iraq. He represents the sons and daughters of all of those people I met all over the world during my military career who were suffering for circumstances completely outside of their control and found themselves caught up in cycles of conflict that they had no way of ending.

If my son Oren decides to be the sixth generation of our family to serve in the military, I hope he doesn’t have to fight the same war for the same reasons that I did. Thank you.

-

Alex Pruden