This post originally appeared as my opening statement in my debate with my friend Steve Blank in The Economist.

We are not in a technology bubble. We have not even taken a major step towards a technology bubble. Predicting such things is a bit like predicting the end of the world; the prediction will eventually come true, but almost everyone who listens to you in the meanwhile will regret having done so.

Let us start by understanding the nature of bubbles. Warren Buffet recently made the following remarks about the housing bubble:

The only way you get a bubble is when a very high percentage of the population buys into some originally sound premise…that becomes distorted as time passes and people forget the original sound premise and start focusing solely on the price action…People overwhelmingly came to believe that house prices could not fall significantly. And since [property] was the biggest asset class in the country and it was the easiest class to borrow against it created, you know, probably the biggest bubble in our history.

So let us first ask if “a very high percentage of the population” has bought into a distorted premise about the future growth prospects for technology. If they have, then we should be able to see some evidence that the dominant public technology companies are moving towards bubble valuations. Here is a telling statement from an analyst on Apple’s most recent quarter:

Apple’s stock price to earnings ratio has dropped to 16.72. Ex-cash it’s 13.5. On a forward basis (my estimates) it’s 8.3. Apple’s valuation is now a case for business historians to discuss because I don’t think there are modern precedents.

—Horace Dediu, Asymco

If we are in a bubble, that is a bit of an odd commentary for a company that grew revenues 83% year-over-year and grew earnings 93% year-over-year. Similarly, Google, well on its way to owning the dominant smart phone operating system and which maintains a near monopoly position in search, trades at a price/earnings (P/E) ratio (ex-cash) of around 13.7.

Amazon trades better than both with a price of 24 times last year’s cashflow. But this is still hardly a bubble multiple. For comparison, the average P/E for the Standard & Poor’s (S&P) 500 over the last 100-plus years is approximately 16x. In the last bubble, the S&P hit 44x in January 2000. Currently, the S&P is trading at 22x.

So it looks like the market leaders are trading closer to recession multiples than bubble multiples. But what about newer companies like Netflix, Salesforce.com, and LinkedIn? All of those companies trade at high multiples. Do they signal that we are moving towards a technology bubble, or are those multiples high for excellent underlying reasons (Buffet’s “sound premise”)? Before we can accurately consider the prices of these firms, we need to note the four main reasons why technology companies should be trading at higher multiples than they traded at in the past.

Generational adoption

“Science advances one funeral at a time.”

-Max Planck

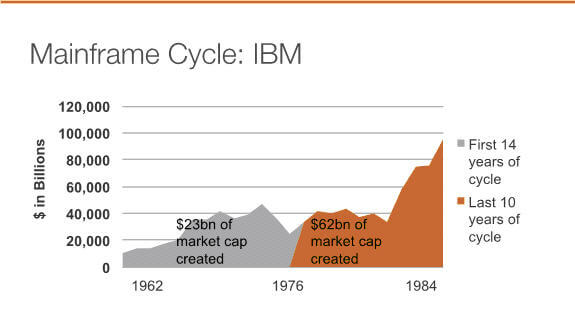

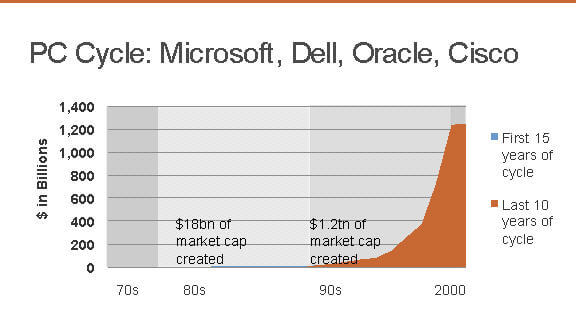

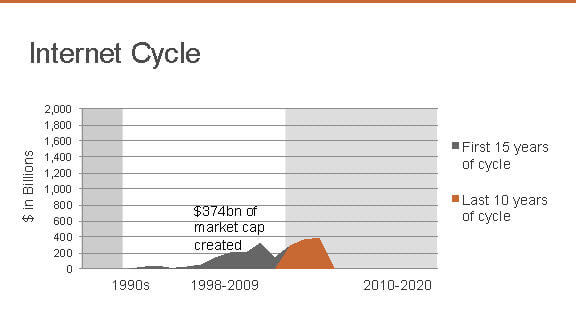

History shows that major technology cycles tend to be around 25 years long with the bulk of the purchases occurring in the last five-to-ten years. This has to do with adoption rates; this period seems about right for the oldest cohorts (less likely to adopt new technologies) to die off and for younger cohorts (quickest to use new technologies) to enter the market.

Let us look at examples of the last two major computing cycles (prior to the Internet).

As you can see, we are poised to hit the major adoption wave for the Internet technology platform over the next 8 years.

The internet is working

A lot has changed since the internet bubble eleven years ago. Firstly, the cost of running an internet application has fallen 100-fold. In 2000, I was CEO of the first cloud computing company, Loudcloud, where the price for a customer running a redundant version of a basic internet application was approximately $150,000 per month. The cost of running that same application today in Amazon’s cloud costs about $1,500 per month.

Secondly, developers are more productive. In 2001, Stewart Butterfield abandoned plans to build a massively multiplayer online game (MMOG) after costs became too great; he built photo-sharing service Flickr instead. Now Stewart’s new company, Tiny Speck, is again building that MMOG, but today it is working brilliantly. Why? Because Stewart’s programmers are ten times more productive than they were in 2001 due to massive advances in programming language technology.

Thirdly, the market is far bigger. In 1998, I was working at Netscape, which owned well over half of the browser market. We had about 50 million users, more than half of them on dialup connections which could not run many interesting applications. Today, there are over 2.1 billion people on the internet, most of them using broadband connections. The true market for internet businesses is about 50 times larger than during the actual technology bubble.

With costs 100 times lower, programmer productivity ten times higher, and the market 50 times larger, it stands to reason that many more internet businesses will work today than did the last time around.

The markets for internet businesses will double in size again over the next five years

International Data Corporation (IDC) estimates that there will be 1 billion mobile internet users by 2013. That estimate will prove to be low. There are currently 4.5 billion mobile phones worldwide; within five years almost all of them will be more fully featured “smart” phones offering better access to the web.

As smart phones become the volume leaders, the component costs for smart phones will fall below the corresponding component costs for low spec “feature” phones—a trend that will eventually render feature phones obsolete. As a result of smart phones replacing feature phones, the internet will double in size over the next five years.

Software is eating the world

Back in 1994, very few people would have predicted that the largest bookseller in the world would be a software company. Today, not only is it a software company, but all of Amazon’s most important competitors are also software companies.

Books were just the first of many industries to be eaten by software. Some other examples:

Magazines and newspapers—really requires no explanation.

Music distribution—the largest music distributor in the world is a technology company, Apple; its largest potential threat, Spotify, is a software company.

Radio—the most valuable radio company in the world is Pandora, a software company.

Animated film—in order for Disney to remain relevant in the animated film industry, they had to buy Pixar, a software company.

Direct marketing—the largest direct marketing company in the world is a software company, Google.

What is next?

Oil and gas—new finds are increasingly software driven.

Financial services—many of which would be far better served by an integrated software platform.

Local business—increasingly present in the online world via offerings from new companies like Groupon, Foursquare and Square.

As software eats one industry after another, the market for technology business expands, rendering previous market size estimates obsolete. That is not to say that no price is too high for a technology company, but there is a fine case that the old prices are too low.

Have we taken a big step towards a bubble?

So now let us look at those high multiple companies (Netflix, Salesforce and LinkedIn) in the context of these underlying trends.

First, Netflix—software is eating the world and Netflix is eating the cable industry. Much like Yahoo once lifted the valuable bits out of America Online (AOL; the US internet company), made them global, and became far more valuable than AOL, Netflix is lifting the valuable bits out of the cable business and making them global. Today, Comcast is worth $66 billion and Netflix is worth $13 billion.

Second, Salesforce.com—the internet is now working and customers like it way better than the old software model. We have over 60 companies in our portfolio and none of them use any products from the current software leader, Oracle. Nearly all of them use Salesforce.com. The company is worth $18 billion and Oracle is worth $158 billion.

Third, LinkedIn—there are now 2.1 billion people on the internet and over 100 million maintain their resumes in LinkedIn. LinkedIn is already quickly becoming the world’s recruiting database, and it seems quite logical that there will be only one (who wants to maintain their resume in more than one place?). LinkedIn has already built a series of popular recruiting products that produced $93m in revenue last quarter. The internet is growing, and LinkedIn looks like it may become a gigantic company.

I am not arguing that the above companies are not overvalued; I am simply arguing that their valuations have not become completely divorced from any rational thought. If they have not, we have not taken a major step towards a bubble.

The problem with predictions

One may still argue that a bubble is coming. A bubble will almost certainly come eventually—that is the nature of human psychology and of markets.

But what is the value of predicting a bubble with no time frame? What does that even mean? If we are approaching a boom and huge growth in technology over the next several years, do you want to miss it due to the eventual bubble? If the true goal of the bubble promoters is simply to encourage caution in investing, when does that advice not apply?

For all of the reasons that I have laid out here, I urge this House to reject the motion before it.