If you were interested in quickly launching a startup, here’s an easy formula for finding product market fit. First, identify an existing product in an industry with a low NPS (like most financial services) that has not traditionally been sold online. Second, create a new digital on-ramp to that existing product, such as digitizing an insurance or lending application. Third, start to buy digital ads to drive customers to said product. Assuming the digital ad market is not yet efficient, there is an opportunity here to quickly scale.

If you were to do this, you certainly wouldn’t be alone. This initial model can be a dangerously attractive way to start a company and has been tried by many financial services startups in lending, insurance, and banking over the years. It’s easy to see why — you can fully control your growth by throttling your spend, and early lifetime value to customer acquisition cost (LTV:CAC) ratios and paybacks are likely to be strong as you take advantage of a market inefficiency. But as competitors, incumbents, or both inevitably enter the market, the businesses that take this approach are forced to either find new distribution channels or expand their margins by cross-selling, upselling, or in some cases, vertically integrating.

In insurtech, a field I’ve been looking at since 2016, companies have focused mostly on the first part of this model during the most recent bull cycle of the last seven years or so. For example, a new business would spin up a digital insurance agency, buy ads to funnel leads to its product suite, and then start to scale. As few companies had built digitally native consumer funnels, these early entrants experienced significant growth, so long as they kept the cost of acquiring a customer lower than the business’s gross margin.

In fact, everyone I met with eight years ago believed that this digital agency was the initial wedge into the market, but nearly every pitch I saw focused on increasing revenue and product control by vertically integrating and forming a managing general agent (MGA). The theory was that as contribution margins started to contract in the commoditized digital agency model, the MGA structure would hypothetically lead to defensibility in the form of higher commission rates (leading to more revenue) and increased product control (leading to higher conversion).

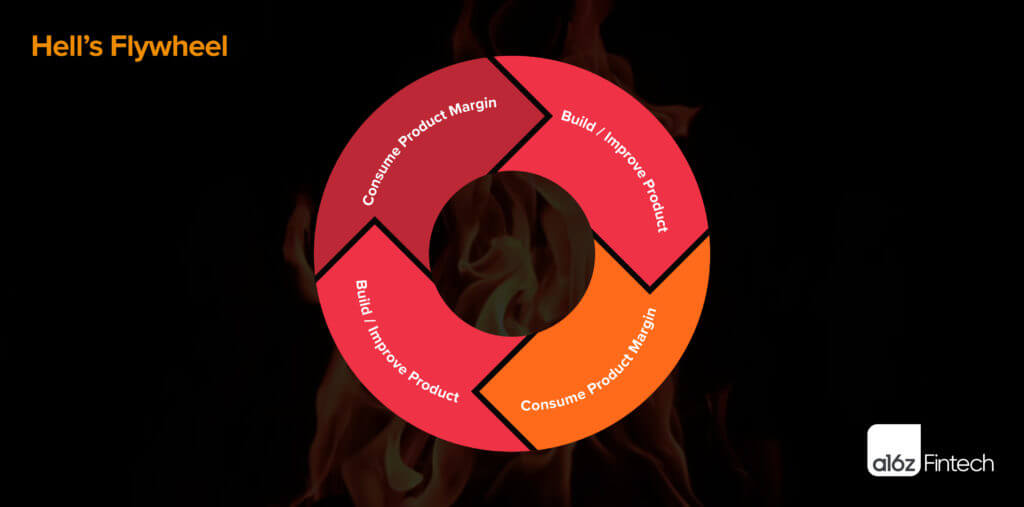

The hypothesis proved to be untrue. Instead of this verticalization leading to competitive moats and defensibility, it instead usually restarted the same vicious cycle of growth. The new MGA would spend a bit more than its non-MGA competitors, until those companies formed an MGA that had the same economics — or the cost of acquiring a customer reached the dollar amount of gross margin a policy generated. This race of margin creation/expansion, consumption, creation/expansion, and consumption is something I’ll call Hell’s Flywheel.

Unfortunately, insurtech isn’t the only place this flywheel has been tested. Businesses and investors who spent time in digital lending during its boom in the early to mid-2010s experienced the exact same downfall. There are countless other industries where the law of Hell’s Flywheel also applies.

Mathematically, there are a handful of ways a company can escape the flywheel and beat back margin destruction: having a lower cost of capital than any competitor (which is extremely unlikely as a startup), having a defensibly higher expected value per lead versus any competitor (perhaps by having either better conversion rates or more monetization methods than a competitor), having a lower cost structure than competitors (such as automation for a scaled call center), or having non-inflationary customer acquisition channels (such as distribution through a referral partner). The first three are exceptionally challenging for any business to achieve as the cost of capital and cost structure advantages are generally only impacted once a company has reached considerable scale, and conversion rates are very hard to sustainably win on. It’s worth noting that without some type of differentiation, your distribution channel may not matter and your margin will erode as competitors enter your channels. But non-inflationary CAC can be a continuous gift.

Non-inflationary CAC can be created in three ways:

- Shifting from B2C to B2B2C

- Shifting from B2C to B2B

- Finding non-democratized B2C channels

The first two methods involve uncovering the B2B business that’s lurking inside every consumer company, and then enabling a partner to either market the product to their customers and retain full customer ownership (B2B), or market the product to their customers and share ownership (B2B2C). Non-democratized consumer channels are places where there is a very deep, proprietary opportunity to market to your customers outside of any auction environment. Often non-democratized channels are only possible at scale but still require a shift in GTM thinking.

Setting the company up for success

Shifting a business’s GTM strategy from direct-to-consumer (D2C) to B2B or B2B2C is no small feat, and in many ways, it can be like starting another company. The customer totally changes as it’s now the business that is selling to the ultimate customer, and the product, marketing, and technology infrastructure all need to change to serve that new customer.

The hardest part of solving this problem is structuring the company to reinvent itself while continuing to operate the existing product that has already hit product-market fit. This generally means taking resources away from the main driver of revenue and allocating it toward activities that might not lead to growth in the short term — and may never lead to growth at all. Doing this takes buy in from the management team and the board, along with a long-term commitment. Most importantly, it takes a team.

Shifting from B2C to B2B2C: I was lucky enough to work at Ethos for a few years as we scaled from $0 to over $100 million in gross profit. I was responsible for a few things during my time there, but most notably, I helped build our B2B2C business, whereby we sold our products through insurance agents. We grew that business from $0 to millions in monthly revenue with thousands of insurance agents marketing products for us. The key aspect of this model was that it had non-inflationary customer acquisition costs, or budgeted CAC, as we could pay referral fees to our partners based on conversions, rather than leads generated. The agents we partnered with already had customers and just wanted a better way of doing business. We were fortunate at Ethos to also introduce new mechanisms that made the business more durable over time, but building an indirect distribution channel was a major win for us and helped us reach our most recent $2.7 billion private valuation.

Shifting from B2C to B2B: An example of a business that successfully shifted from B2C to B2B is Marqeta. Marqeta started in 2010 as a prepaid card business. Instead of using an existing legacy infrastructure such as FIS or First Data, Marqeta opted to build its own issuing and processing platform to support its new card. Unfortunately, the company wasn’t able to scale the first or second direct-to-consumer card idea and escape Hell’s Flywheel. Instead, the business pivoted into offering the platform it had built to support its own cards to other businesses, such as Square and Doordash, which had already acquired clients and wanted to better serve them. Marqeta is now a roughly $3.4 billion public company.

Shifting into non-democratized channels: Hims is a business that’s known for reinventing consumer healthcare delivery and started with men’s products. Early on, digital channels for other healthcare delivery services were inefficient and the company was able to scale rapidly. Once at scale, they did some very clever non-inflationary advertising, such as buying restroom/urinal space at Oracle Park. Zappos also used non-democratized channels when they essentially bought advertising spots at the bottom of all the TSA trays at a few regional airports so they remind the shoe-less passengers staring at the bins they should buy their next set of kicks from Zappos. Both are examples of non-democratized and non-inflationary distribution channels that are possible after reaching scale.

As the focus returns to positive unit economics and defensibility, more companies will inevitably run into issues scaling direct-to-consumer offerings and will turn to trying to create budgeted distribution. If your company is going to go through this type of transition, here are a few thoughts on how to structure the transition:

- Decide between shifting to B2B2C, B2B, or non-democratized: The hardest part about starting something new is to figure out which direction to run in. At Ethos, we simultaneously tried a handful of things, all of which were informed by where products similar to ours were already selling (~89% of life insurance is sold through an agent and 50% is sold through an independent agent). My partner Alex has a wonderful piece on when B2B2C business models make sense where he states that B2B2C is “easiest to sell when Business A does NOT want to be in the business you are offering.” The agents we worked with were in the business of selling products, not manufacturing them, so it was complimentary. If a prospective partner does want to be in the business you’re offering, it might be simpler to choose white label B2B so long as there’s a clear reason for adoption.

- Re-establish a startup mindset. By this, we encourage you to keep your team lean, as overstaffing can kill these new efforts, and ensure your builders are as close to the customer as possible. To start, this might be one generalist and one technologist, much in the same way a startup might begin. Make sure every team member is hungry, even if this means hiring less tenured employees over established executives. And remember to take a long view; one of the biggest mistakes companies at this stage make is not adequately funding — financially or with head count — their new business unit and giving the team enough time to execute.

- Ensure teams are self-reliant. Make sure that your teams have everything they need to build and don’t have to rely on the mothership for resources. For example, if you are building a new initiative, you don’t want to rely on the VP of Engineering to allocate resources to your sprint, because he or she probably cares more about building and maintaining your company’s core product experience and won’t prioritize working on anything new. At times, this may mean different teams are doing duplicative work, but this redundancy actually helps the new initiative move faster in the short term while also potentially protecting it from changes in the core experience. For example, when we were working on the early versions of the agent business at Ethos, our engineers copied over many sections of the code base so our agent-based product experience was not impacted by the tests we ran on the consumer funnel.

- Create go / no-go deadlines. It’s critical the new team has room to fail fast and figure out what works and doesn’t work. As there’s considerable ambiguity with the new initiative, adding a timeline to experiments can help avoid creep and allow you to make decisions faster. For example, the team may want to set a goal around solving for a specific problem by a set date, such as “by our next fundraise we need to have proved XX” or “we are funding this with $Y; to unlock more money here’s what needs to happen.”

While using growth channels you can easily toggle up or down can be deceptively attractive, the unfortunate reality is that there is no alpha in paid marketing and many businesses can greatly benefit by building the sustainably profitable distribution channels described above. If your business is stuck on Hell’s Flywheel, I hope these thoughts give you peace of mind that escape is possible and has been done many times before. Following the above steps and connecting with others who have been on the journey before can greatly increase your chances of success. And as with any startup, above all else hire and empower the right people and the results will take care of themselves.