Steve Jobs famously sold the iPhone as three inventions in one. In truth, it represented something much more foundational: the first mass-market machine that bundled compute, power, sensing, connectivity, and software into a single, tightly-engineered package.

Once that blueprint existed, everything else started to look the same. Your laptop, smart TV, thermostat, doorbell camera, refrigerator, industrial robot, drone: all of them follow the same basic recipe. Even an electric vehicle, once you peel back the sheet metal, relies on the same ingredients — batteries, sensors, motors, compute, and software, just in a different skin. We no longer live among truly distinct technological paradigms, but within a world of variations on one single idea: the smartphone, endlessly turned inside and out and scaled across every domain. Everything is a smartphone. Everything is computer.

There is an irresistible evolutionary logic to why so much of the modern technological world converged on this form. Consumer electronics are unique because they sit on a deeply modular foundation: systems can be broken down and recomposed into entirely new products with surprising ease. The same polymers, diodes, and battery cells that power an industrial robot are just as at home in a laptop. Capability concentrates at the product level, but scale accumulates far below it.e

That is why the “modular middle” of the electro-industrial supply chain ultimately determines both commercial and geopolitical success. This layer is what allows electronics to be built, customized, and improved faster than any other class of physical goods, while drawing on vast consumer-scale commodity markets to create new systems by recombination. It’s how a company like Xiaomi could move seamlessly from smartphones into electric vehicles. Control over this integration step shapes cost curves, sets performance ceilings, and determines who can reliably build complex products at scale.

Mastery of the modular middle can confer a decisive advantage in electro-industrial production — and with it, disproportionate influence over the pace of technological progress this century. China understands this. The United States largely does not. If we want to compete, we must fill in this “missing middle.”

Rise of the electro-industrials

Think, for a moment, about what your smartphone is made of. A smooth slab of glass and metal crammed with nanometric transistors, atomic sensors, lenses that bend light like a studio camera, a power source that can be recharged thousands of times without ever catching fire; all of this perfectly interlocking and operating at their thermal and mechanical limits, and all snugly integrated with software that makes this supercomputer not only remarkably powerful but also easy and even fun to use. And this remarkable device ships in the billions at consumer prices, with near-zero rates of failure, on rigorous annual redesign cycles, with perpetual process improvement every year. Nothing before in human history has demanded that level of integration at scale, and meeting those requirements required the creation of a vast global supply chain capable of mass-producing ultra-complex systems at unprecedented speed.

What makes this remarkable process practical at all, let alone feasible at such a regular tempo? Scale.

Consumer electronics is about scale; and at scale, even the most marginal improvements matter. When you ship hundreds of millions of units, small gains in cost, efficiency, size, or reliability compound directly into better products and fund the next iteration. And in a market that large and competitive, companies don’t just assemble systems. They rethink the modules inside them.

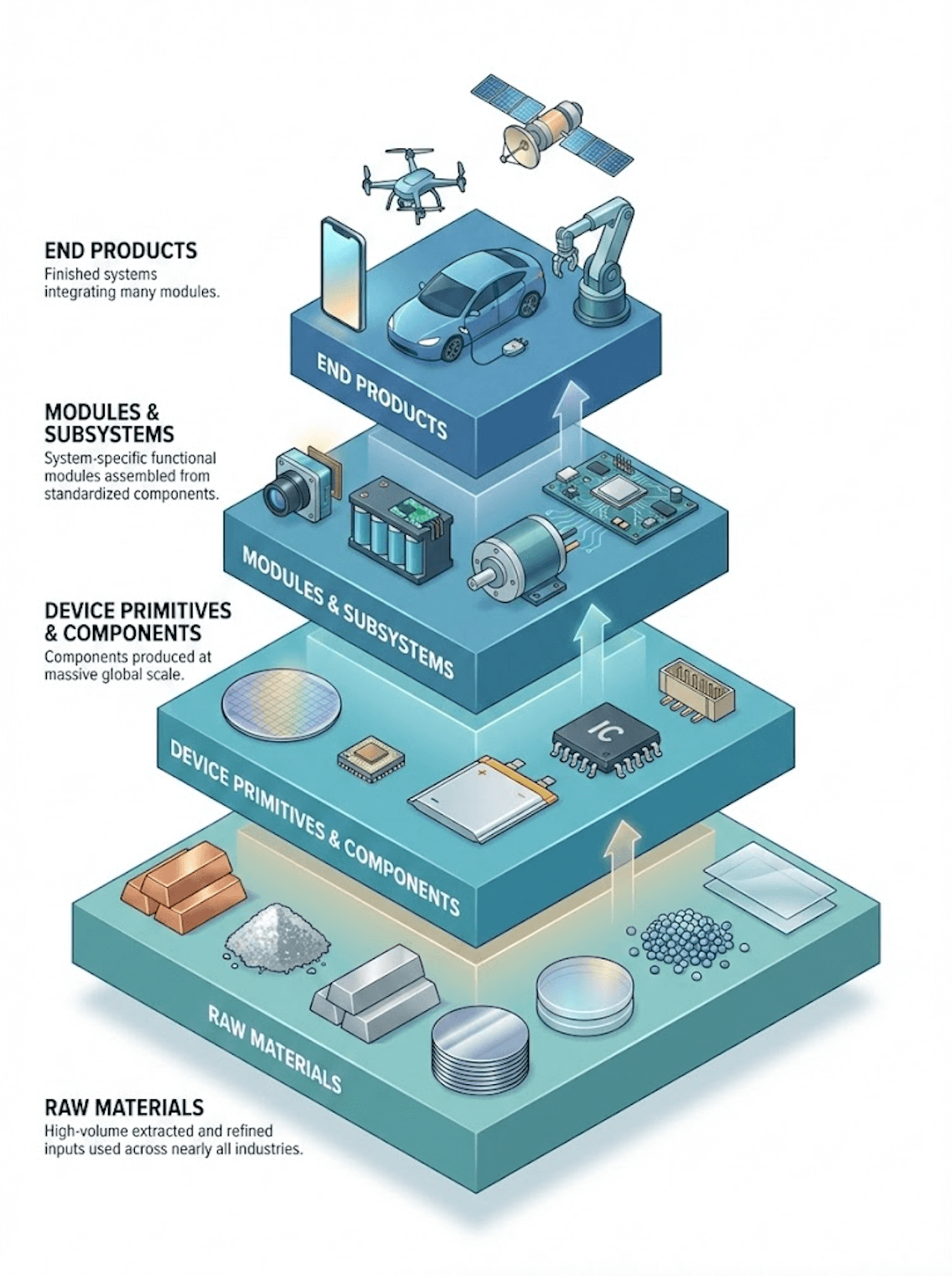

By modules, I mean the integrated subsystems that form the middle layer bridging low-cost components and high-value finished products. At the lowest level, ultra-commoditized materials like wafers, foils, and polymers are produced at massive scale and combined into standardized primitives: diodes, electrodes, windings, lenses, passives. The modular middle packages these primitives into functional building blocks, abstracting away unneeded complexity and allowing OEMs, original equipment manufacturers, to effectively tap into mature, high-volume supply chains that sit upstream.

Consider some examples. Higher-voltage SiC MOSFET switches are cheap, but turning them into a thermally stable inverter that can manage the load profile of a car is challenging. Drone motors use standard magnets and windings, but producing a sealed, vibration-tolerant motor that can keep a quadcopter stable in flight is its own craft. The inputs to batteries are commoditized chemicals; the difficulty lies in converting them into high-yield cells that can be integrated into compact, reliable packs. Each of these subsystems takes abundant, low-cost components and transforms them into something packaged, validated, and fine-tuned for a specific end-product competing in brutally competitive commercial markets.

Compare the consumer electronics stack with the traditional auto industry. Early automakers were vertically integrated — Henry Ford’s Rouge River plant being the classic example, with raw materials entering the factory at one end and finished cars exiting through the other. But as automobiles grew more sophisticated, car companies evolved into high-level integrators of bespoke subsystems designed and manufactured by phalanxes of tier-one suppliers. Firms like ZF, Bosch, and Aisin (Toyota) came to own much of the car’s architecture, which is why different automakers would often share the same underlying systems. Mazda and Lotus, for example, use Toyota drivetrains.

This was the automotive industry’s attempt to chase scale: sharing core subsystems across brands to amortize cost and complexity. But even at its best, this model never approached the volume dynamics of electronics. Automotive subsystems were still designed almost exclusively for vehicles and tightly tailored to specific platforms or regulatory regimes. The result was scale within a narrow domain, not participation in a broad, cross-sector ecosystem. More of the vehicle would be ceded to suppliers over time; incentives favored risk offloading, regulatory lock-in, and supplier-led customization. Carmakers retained assembly and branding, but stitched together supplier-defined systems. The result was an industry that neither controlled its core technologies nor captured the cost-performance curves and spillovers emerging elsewhere.

From its earliest stages, the consumer electronics ecosystem evolved along very different lines. Unlike legacy internal-combustion vehicles, electric vehicles draw heavily on components and device primitives shared across many other industries. Consumer electronics was built on broadly reusable components produced at massive scale, even as modules were custom-designed to meet demanding end-product requirements.

At first, off-the-shelf modules often couldn’t meet consumer requirements. When Apple pushed Sony on cameras, for example, existing sensors fell short. But beneath the module layer, the same device primitives were already being produced at an increasingly massive global scale. Electronics OEMs kept control of module design and built systems on top of those shared inputs with the help of modular middle suppliers. And because those inputs were used across phones, laptops, and industrial equipment, improvements spread quickly, pulling down costs and pushing up performance in a way the automotive industry never could.

Much of today’s most important technology rests, almost inadvertently, on the foundations built by that modular ecosystem. Lithium-ion batteries perfected for phones made electric vehicles viable. MEMS accelerometers built for screen rotation now stabilize drones and robots. Smartphone cameras became the eyes of autonomous systems. Wi-Fi and Bluetooth chips evolved into the backbone of connectivity. Mobile-class processors now fly in spacecraft because they outperform bespoke aerospace hardware. And of course, GPUs built for video games became the engines of modern AI systems.

Consumer electronics underpin all of the most important technologies of our time. And everything, absolutely everything, is based on the indispensable paradigm of the smartphone. An electric vehicle is a smartphone with wheels. A drone is a smartphone with propellers. A robot is a smartphone that moves. The differences matter, of course, but the family resemblance is impossible to ignore.

This explains why so many electronics companies — especially in China — now appear to be building many different types of products at once. From the outside, this looks like reckless sprawl. From the inside, it is straightforward reuse. The products change; the components do not. A company that builds smartphones at global scale already understands batteries, sensors, compute, thermal management, wireless stacks, and high-volume manufacturing. To build electric vehicles, it doesn’t need much more than that.

In December, the technology YouTuber Marques Brownlee showcased a new Chinese EV. It was a $40,000 electric sedan with the performance and polish of a Porsche. What was remarkable wasn’t that a Chinese firm had produced an impressive EV; it was that the firm in question was the smartphone company Xiaomi. Such industry “crossovers” are common in China. BYD, the global leader in batteries, builds cars, buses, ships, and trains. DJI makes drones, but also cameras, radios, and robotics hardware. These firms are not “diversifying” in the traditional sense. Rather, they are doubling down. They are repeatedly assembling the same electro-industrial stack — batteries, power electronics, motors, compute, and sensors — into new permutations.

The same pattern is visible across Asia. A company that excels in one corner of consumer electronics is capable of excelling in practically every other. Sony builds game consoles, sensors, cameras, smartphones, and robotics. Panasonic makes cameras, batteries, avionics, EV components, and appliances. Samsung produces smartphones, memory, displays, appliances, and industrial equipment. LG develops displays, batteries, HVAC systems, appliances, and robotics. These firms keep recombining the same underlying competencies into different physical forms. Their advantage is not breadth for its own sake, but mastery of a single electro-industrial production model that can be applied almost without end.

The defense electro-industrial base

Which brings us back to America.

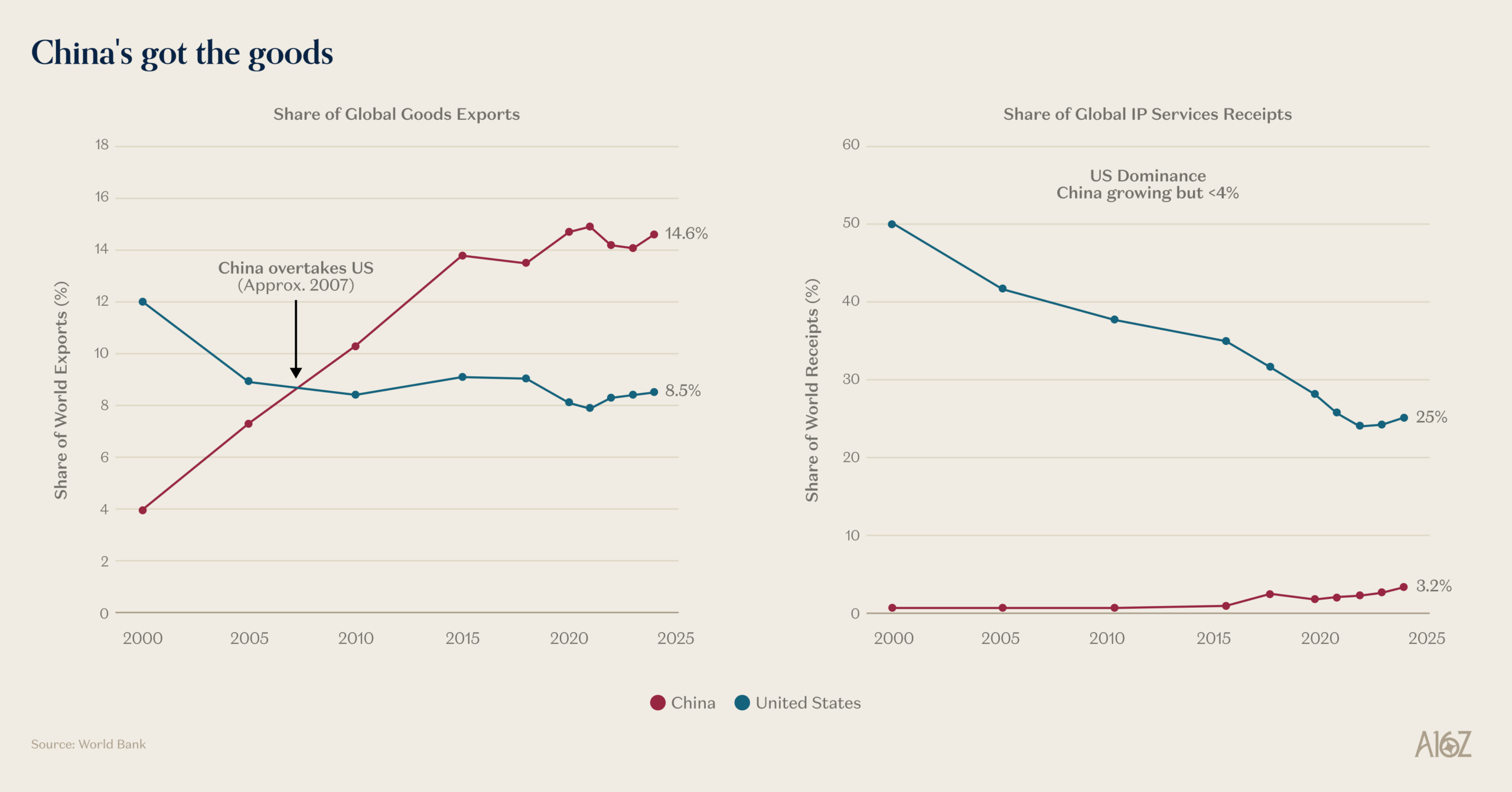

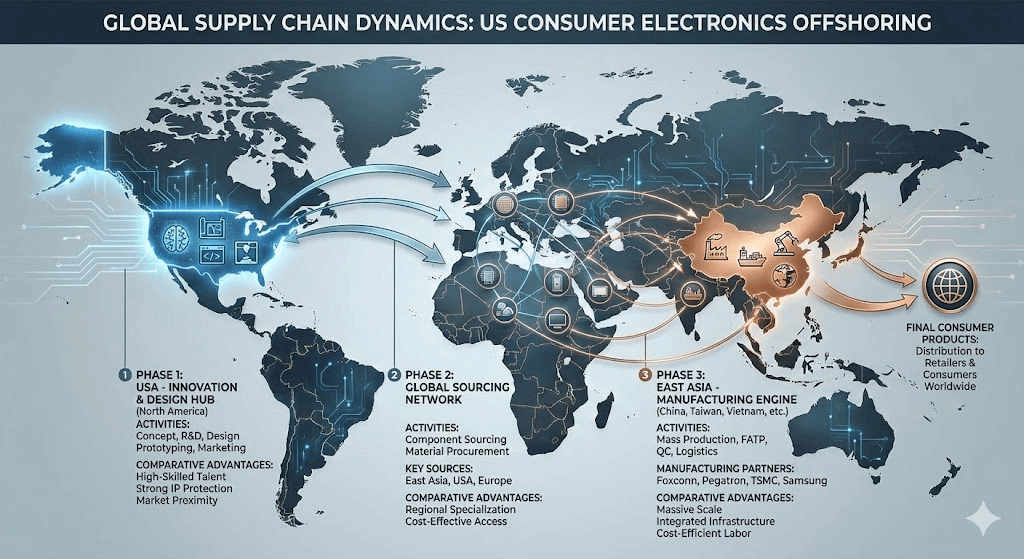

It’s a myth that the United States “lost manufacturing,” as if we’d misplaced our industrial sector or gambled it away. We made the conscious decision to stop being a country that manufactures things. We told ourselves that the real value was in design and IP, while the physical act of manufacturing was a low-value task that other people could handle. Modules and their components were the ingredients, and we were the head chefs directing legions of line cooks. Why should American companies care where batteries, motors, displays, or power electronics come from, as long as they design the final system?

But that logic ignored a harsh reality: if a country supplies every critical module in a supply chain, it’s not hard for that country to assemble the final product itself. And nowhere was that dynamic more pronounced than in consumer electronics.

In modern consumer markets, tiny errors are catastrophic. Every small improvement that can be eked out of a production process matters immensely, and every percentage point of yield, cost, and reliability becomes a matter of basic survival. Hitting those targets requires genuine technical breakthroughs across materials science, thermals, EMI behavior, and manufacturability. In the language of mathematics, the optimization problem is non-convex: there are countless local minima and false starts that can only be conquered by constantly building, learning, iterating, and building again. That constant pressure fuses manufacturing and research into a single engine, creating an industrial competence that compounds over time.

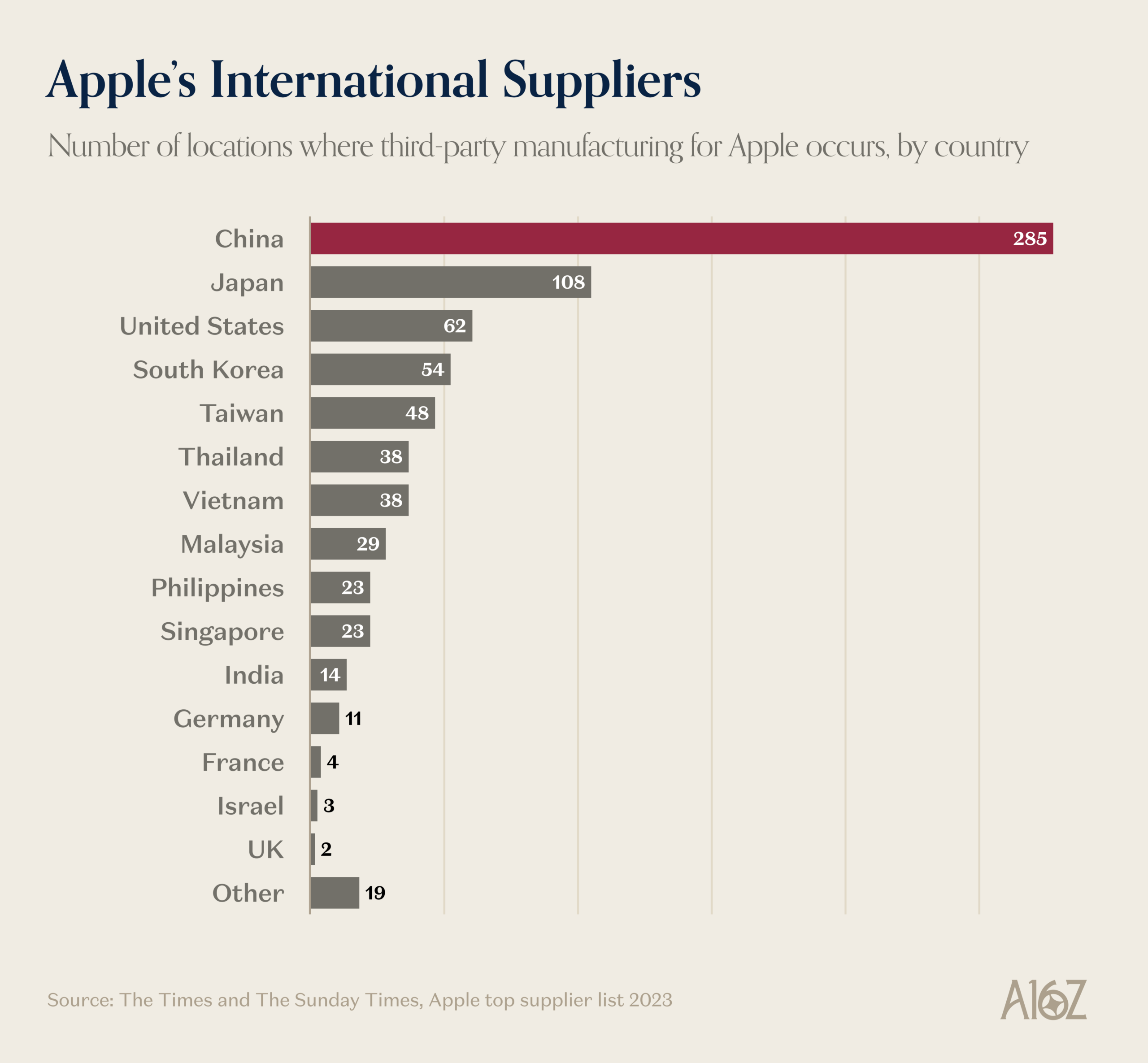

Apple understood this early. They poured billions into China, training factories, funding tooling, building new process capabilities, and effectively creating a distributed applied-research ecosystem inside each of their suppliers. What began as an effort to squeeze cost and defects out of the iPhone turned into one of the most demanding production engineering challenges of all time. And it was solved beautifully — but on someone else’s soil.

Tesla took that same industrial engine and pushed it into a new domain. When Tesla committed to Shanghai in 2018, Li Qiang — then the city’s top official and now China’s second-in-command — personally cleared obstacles, aligned national and local incentives, and helped stand up a world-class factory in under a year that now produces half of Tesla’s vehicles. The exchange reshaped both sides: Tesla gained velocity, cost discipline, and enormous market access; China absorbed Tesla’s production philosophy and leveled up its suppliers. Companies like CATL, LK Group, and a broader constellation of local firms honed their capabilities by meeting Tesla’s brutal standards for quality, speed, and scale. An ecosystem that had once been a “fast follower” soon became a global frontrunner — not just in EVs, but across each node of the entire electro-industrial stack.

The strategic consequences are enormous. Where innovation once flowed from defense and automotive firms into consumer markets, today it moves in the opposite direction. The future fight isn’t just about stamping steel; it’s about drones, spectrum warfare, power management, resilient communications, and hardened compute — systems built from the very modules and processes perfected in Shenzhen’s factories, not Detroit’s.

The late aerospace republic

America is often called an “aerospace republic” because it remains a domain of clear dominance. The industry is shielded by ITAR, and unlike EVs or drones, aerospace still relies on high-power turbomachinery that cannot easily be replaced by electrical systems tied into the global electronics supply chain. We remain the world’s best in thermodynamics; in fact, more countries can build nuclear reactors than can build top-tier gas turbines.

But this moat is shrinking. Aerospace and defense platforms are rapidly becoming electric and software-defined. Avionics, power distribution, motor controllers, and autonomy now matter as much as the airframe or combustor.

Everything that can be electrified will be electrified, because electric systems are the native substrate for code. Power electronics become the transmission, motors become the engine, and software becomes the differentiator. Across land, sea, and air, mobility is shifting to battery-electric and hybrid architectures. Rockets are the lone exception — chemical propulsion still dominates on thrust-to-weight ratio — but even these systems are increasingly going electric. Starship carries hundreds of kilowatts of power electronics and the same Tesla batteries you’d find in a Model 3 or Powerwall. The rocket equation stays chemical; everything around it becomes electrical.

Our aerospace moat that defines much of our defense prowess is far less secure than it first appears. It’s true that America still excels at turbomachinery; but we’ve offshored nearly everything else.

The major exception is Elon Musk. Tesla and SpaceX have built tens of millions of units in the United States, and a Model 3 has more in common with a Starlink satellite than with a legacy car: tightly-integrated electronics, high-density power systems, aggressive thermal management, OTA updates, and factories built for continuous iteration. It’s the same consumer electronics playbook being executed across Asia as we speak.

The lesson of Musk’s success, however, is not blind vertical integration. SpaceX only in-houses what the market cannot deliver. They build engines, tanks, and custom avionics because no supplier can meet their schedules. But they also work with STMicro for power ICs, Samsung for modems, and Xilinx for FPGAs. Even Starship depends on those batteries built through Tesla’s long-standing partnership with Panasonic.

The differentiator is that SpaceX fully owns the subsystem design and can credibly threaten to in-house any part that doesn’t meet its standards; and they proved this threat to be credible early on, when they in-housed production of their engines and structures. Electronics has kept up longer thanks to its scale and capability, but even that edge is narrowing as iteration gets faster, specs get tighter, and volume grows — which is why SpaceX now runs the largest PCB factory in the country, and is investing aggressively in advanced chip packaging.

Musk’s real insight is that cars and spacecraft should be built the way smartphones are — engineer the production system first, shape every subsystem for manufacturability and integration, and rely on existing high-volume supply chains and relentless process improvement for as long as physics allows. Musk’s companies appear unrelated: but together they form a cohesive electro-industrial conglomerate built on a common production model that others must follow to survive.

The arc toward boring excellence

When a technology becomes a consumer electronic, it follows the same arc: it starts life as a fragile miracle; then an interesting and novel product; then a boring commodity. Cars drive themselves, drones become expendable, robots leave labs, and cameras collapse into chips. Scale unlocks democratization: high-volume manufacturing lowers price, simplifies use, and spreads advanced capabilities to everyone on Earth. You, your friends, a shopkeeper in Lagos, and the President of the United States all carry the same smartphone.

This is an unprecedented global success, but left unattended it also creates a national security vulnerability. Defense-critical capabilities now emerge from the same process improvements that drive consumer electronics. The country that masters those processes gains the skills needed to shape the strategic industries of the future.

Today, the United States lacks serious modular middle firms that bind together the electronics ecosystem. Exceptional figures like Elon Musk have succeeded despite this by aggressively plugging into global supply chains and then pulling critical modules in-house over time. But that is not a reproducible strategy for the world ahead. We cannot make national success contingent on finding a hundred more Elons able to vertically integrate down to a screw. If we want the default choice to be American — fast, competitive, and reliable — we need to rebuild the missing layer. Reclaiming our electro-industrial future starts with building an American modular middle.

Critically, the goal is not deep vertical integration in the style of BYD or SpaceX. Even the best companies don’t — and shouldn’t — have to build everything themselves. Winners own system architecture and design key modules with scaled suppliers, concentrating differentiation where it actually matters: integration, software, and the customer. When a supplier can take a spec — a power system, motor driver, flight controller, thermal assembly, — and ramp it quickly using familiar parts and processes, development becomes fast, cheap, and repeatable. The aim is to anchor your product’s supply chain in as many massive markets as possible. This is the electro-industrial model worth building: architects define the system, upstream firms provide low-cost components at scale, and integration turns them into globally competitive products. Not all together inside a single firm, but across an ecosystem — here, in the United States. That’s how you get low-cost EVs, mass-produced satellites, and consumer-grade robotics in America.

And the solution must begin at the earliest stages of company formation. American startups lead in product vision, but often struggle to find suppliers willing to prototype alongside them, iterate quickly, and then scale with demand. Without a functional middle layer, these companies are pushed into premature vertical integration, sacrificing their core advantages of speed and focus simply to get products shipped.

This same gap has also pushed much of the mature American electronics sector toward foreign ODMs — original design manufacturers like Foxconn and Quanta that both design and build the product while their American partners focus on brand and distribution. HP, Dell, Lenovo, Amazon, and most appliance makers now rely heavily on this model. Between ODMs and vertical integration sits the hybrid JDM model — joint design manufacturing — where OEMs and suppliers co-design modules from the start, as with Apple and Sony on optics or Tesla and Panasonic on cells. Today, both the ODM and JDM models depend on a deep and capable ecosystem that the United States simply doesn’t have.

When companies are forced into vertical integration or risky foreign supplier bets, it’s a sign of market failure. A healthy industrial base depends on diverse suppliers who can adapt to customer requirements quickly and scale capacity on demand. Companies like Diode hint at what’s possible for PCBs, but America needs a far larger bench of key suppliers across every part of the electro-industrial stack — sensors, motors, batteries, compute, power electronics, and beyond.

There is tremendous reason for optimism. America leads in product and module design, and the upstream materials and device primitives we need are, for the most part, increasingly available. We also have the world’s deepest and most demanding consumer markets, and the brands best positioned to serve them. On paper, this should put the United States in a strong position. But in practice, closing the production gap will require a significant and durable shift to support an electronics ecosystem that now spans consumer products, industrial systems, and defense applications.

We may never match Shenzhen’s sheer density of low-cost suppliers. But software can help us stitch together a distributed manufacturing network of highly automated factories — not just to reshore high-volume production, but to continuously drive down the marginal cost of new product iteration. Without this, domestic manufacturing becomes increasingly static, bespoke, and expensive, while foreign competitors’ advantages compound through faster iteration. At the same time, we must be careful about lax subsidies that merely entrench incumbents or suppress competition; industrial policy that rewards presence rather than world-class performance will create lethargic firms vulnerable to the hyper-competitive dynamics of Asian markets. Finally, we should be intentional about inviting firms to build their production ecosystems here to learn from. American firms repatriating capabilities offshored decades ago are not the same as foreign firms just extending theirs.

America started this race with the smartphone in all of our pockets. We built the blueprint for the consumer electronics revolution; others scaled it. The billionth unit is always better and cheaper than the first. The next decade will determine whether our ecosystem remains merely architects or becomes builders. That depends on whether we can manifest the industrial layer we left behind. We will do this not through nostalgia for the factories of the past, but through mastery of the production model of the future. America invented the smartphone. Now we need to learn its lesson: the future belongs to whoever can build it.