Leia esse artigo em Português. / Lee este artículo en Español.

The Brazilian fintech company Nubank is now the largest neobank in the world, with 33 million customers and a $25 billion valuation. That valuation is already half that of Itau’s market cap, the largest public bank in Brazil, which has been around for more than 75 years. Even among fintech enthusiasts, Nubank’s rapid rise seemed to come out of nowhere—from slightly more than 1 million applications in 2016 to more than 30 million in a few short years. Nubank has become one of fintech’s most impressive companies in terms of scale, growth, and velocity. One key advantage? Nubank figured out early on what has since become obvious to the rest of the world: there is an enormous amount of untapped opportunity in Latin America for financial services of all types.

As is often the case, growth appears gradual for a long while, then happens suddenly, seemingly all at once. Latin America is currently experiencing an explosion of fintech activity, and this is just the beginning. Here, we unpack the key market dynamics that make Latin America a promising place to start a fintech company, the tailwinds and headwinds in the region, and where we see opportunities for the next billion-dollar companies to emerge.

There’s a large, latent demand for fintech in Latin America

In Latin America, financial services have notoriously low adoption rates; the majority of consumers are still underbanked or unbanked. This extreme demand sets the stage for new fintech players to both better serve existing customers and introduce consumers to the formal financial system for the first time. There are many systemic reasons for this historic lack of financial services, including:

1. Latin America is large

The region is home to more than 650 million people across 33 countries. Its two largest countries, Brazil and Mexico, have populations of 210 million and 130 million, respectively, and GDPs of $1.8 trillion and $1.3 trillion. Other countries in the region have also reached significant scale, including Colombia (50+ million people; $300+ billion GDP), Argentina (45 million people; $445 billion GDP), and Chile (19 million people; $280 billion GDP). Building a company in Latin America provides an incredibly large addressable market to build better products and distribute them to a vast number of eager new customers.

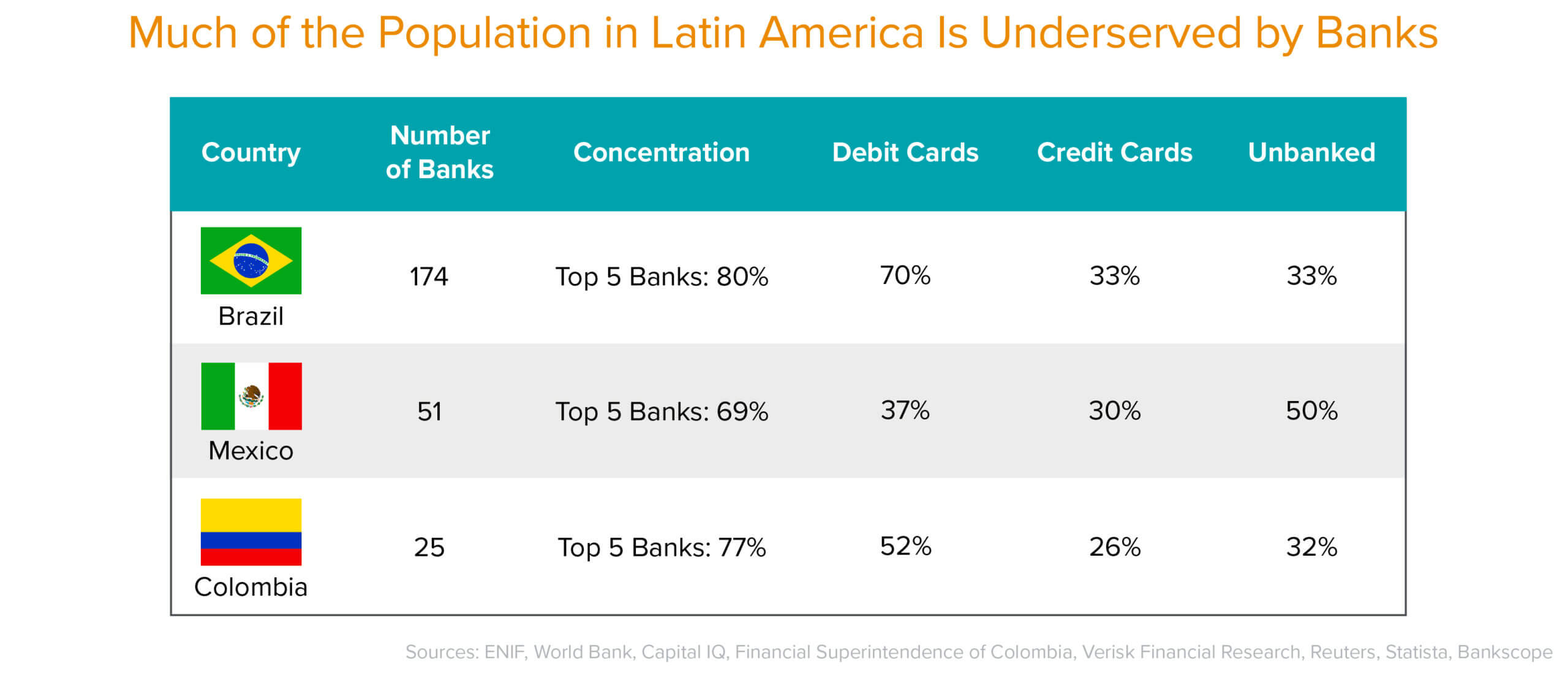

2. Latin American banks cater to the affluent

By embracing stringent underwriting requirements and limiting access to financial products, incumbent banks in Latin America exclude a large portion of the population. In Mexico, for example, over 50 percent of people are unbanked, over 30 percent have no access to any financial product, and just 31 percent have access to credit products. Credit, which is a powerful tool for individuals to afford college, start a business, or buy a home, is also extremely expensive and not readily available to most. As a result, there is massive pent-up demand from customers who have historically been locked out of the financial system by incumbent financial institutions.

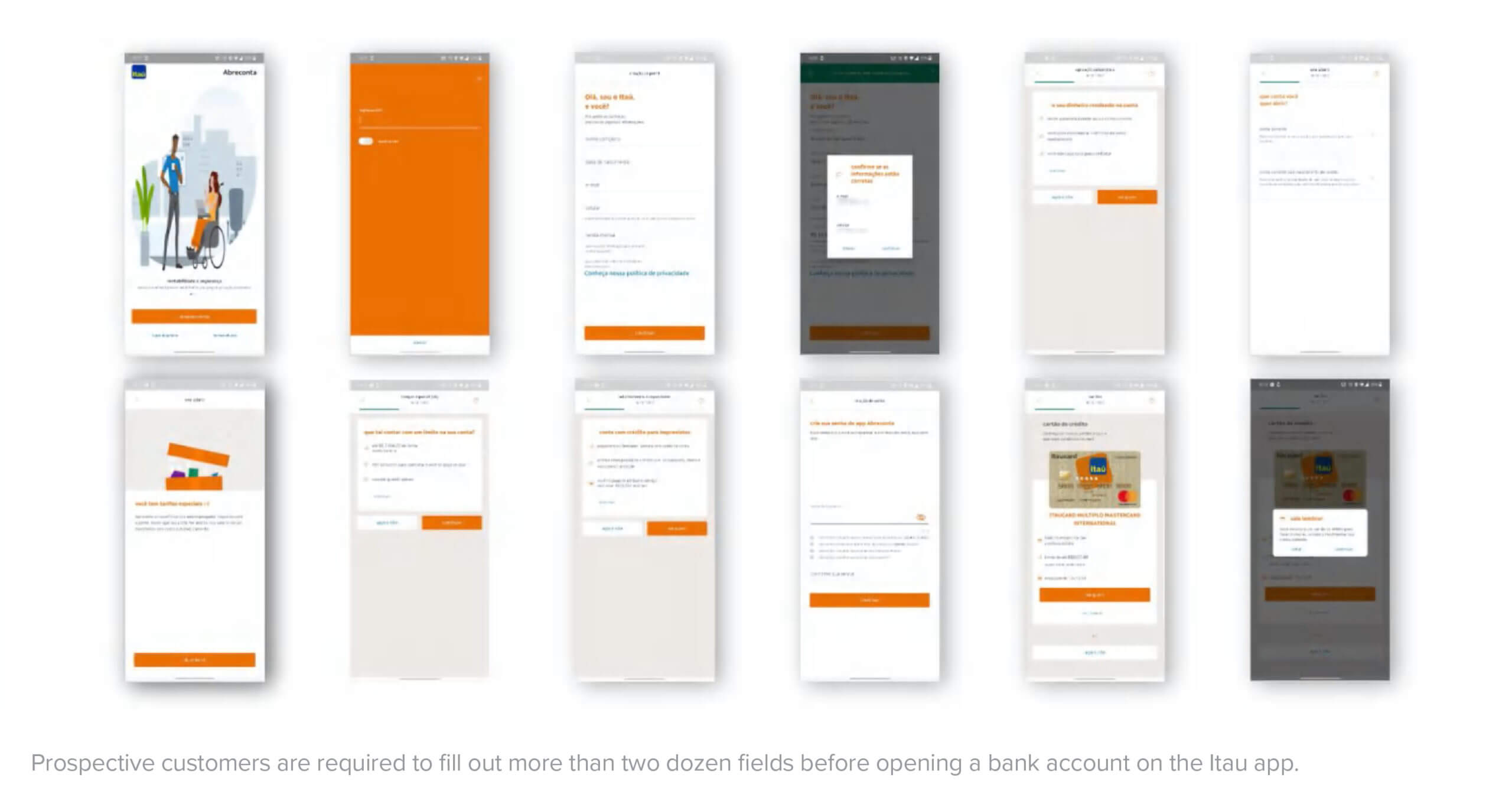

3. For those that are served, the digital banking experience is underdeveloped and inefficient

Until recently, most banks in Latin America didn’t have a mobile app and required in-person banking for the majority of their users. In Colombia, for example, consumers must still visit a physical branch to open a bank account and for many other services. Banks have long ignored tech-driven, mobile-first approaches; for consumers, the digital banking experience is often sorely lacking. At Itau, one of the largest banks in Brazil, for instance, prospective customers must fill out 26 fields—which takes more than 15 minutes—to open an account on its app, according to Idwall. If that wasn’t enough of a deterrent, it takes another 18 hours for the account to get approved! And this in itself is a significant improvement: five years ago, applicants had to visit a branch in-person to open an account, then wait weeks for approval.

4. Economies are largely cash-based

The Latin American economy still relies heavily on cash—in Mexico, more than 90 percent of payments are in paper money; in Brazil, it’s around 70 percent. Though ecommerce has seen a dramatic surge over the past year (Mexico, for example, saw a 32 percent year-over-year increase in 2020), buying products online is still relatively latent, as only a subset of the population have the financial products to participate in these online economies. In fact, the default for most customers in Latin America is to order online, then pay at the local convenience store in cash. As economies around the world have shifted to digital and card payments, Latin America is poised to take a similar trajectory.

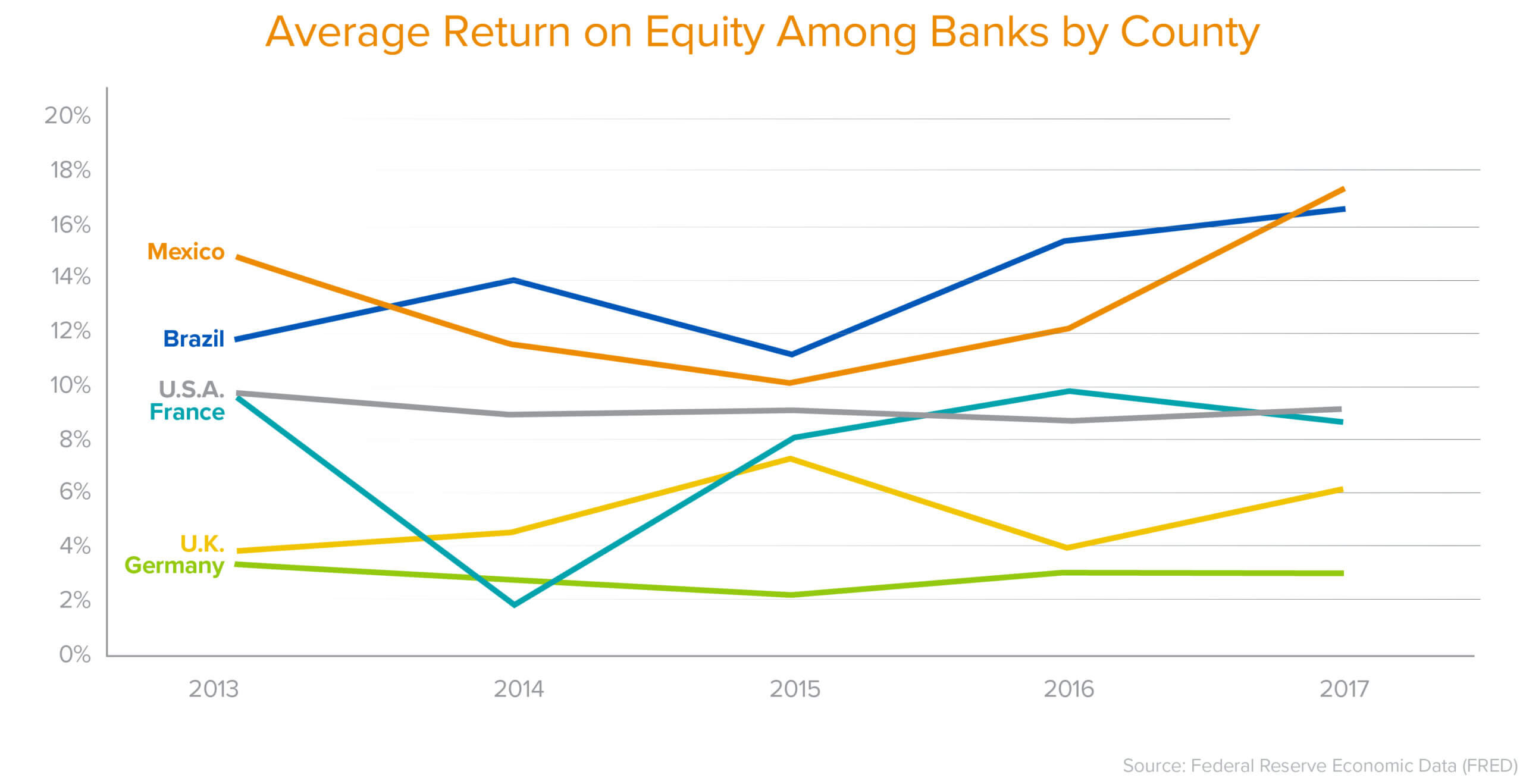

5. “Your margin is my opportunity”: Latin American banks are some of the most profitable in the world

Big banks in Latin America have had few incentives to innovate. In Mexico, there are 51 banks. Colombia only has 25. Compared to the thousands of banks in the U.S., there is a significant delta in the number of choices consumers have. The low amount of banks in the region is exacerbated by the extreme bank concentration and monopoly the largest institutions have. For example, in Brazil 80 percent of deposits are concentrated in the country’s top five banks. This creates mismatched incentives between the financial institutions and their customers. As a result, banks in Latin America have some of the healthiest margins of any financial institutions across the globe. In Mexico and Brazil, the return on equity, or ROE—a metric useful to understand bank profitability—hovers around 18 percent, almost five times that of French banks and twice that of American banks. These large profit pools are indicative of the opportunity for fintechs to offer better, more accessible, and more affordable products for consumers.

A combination of factors indicate a tipping point

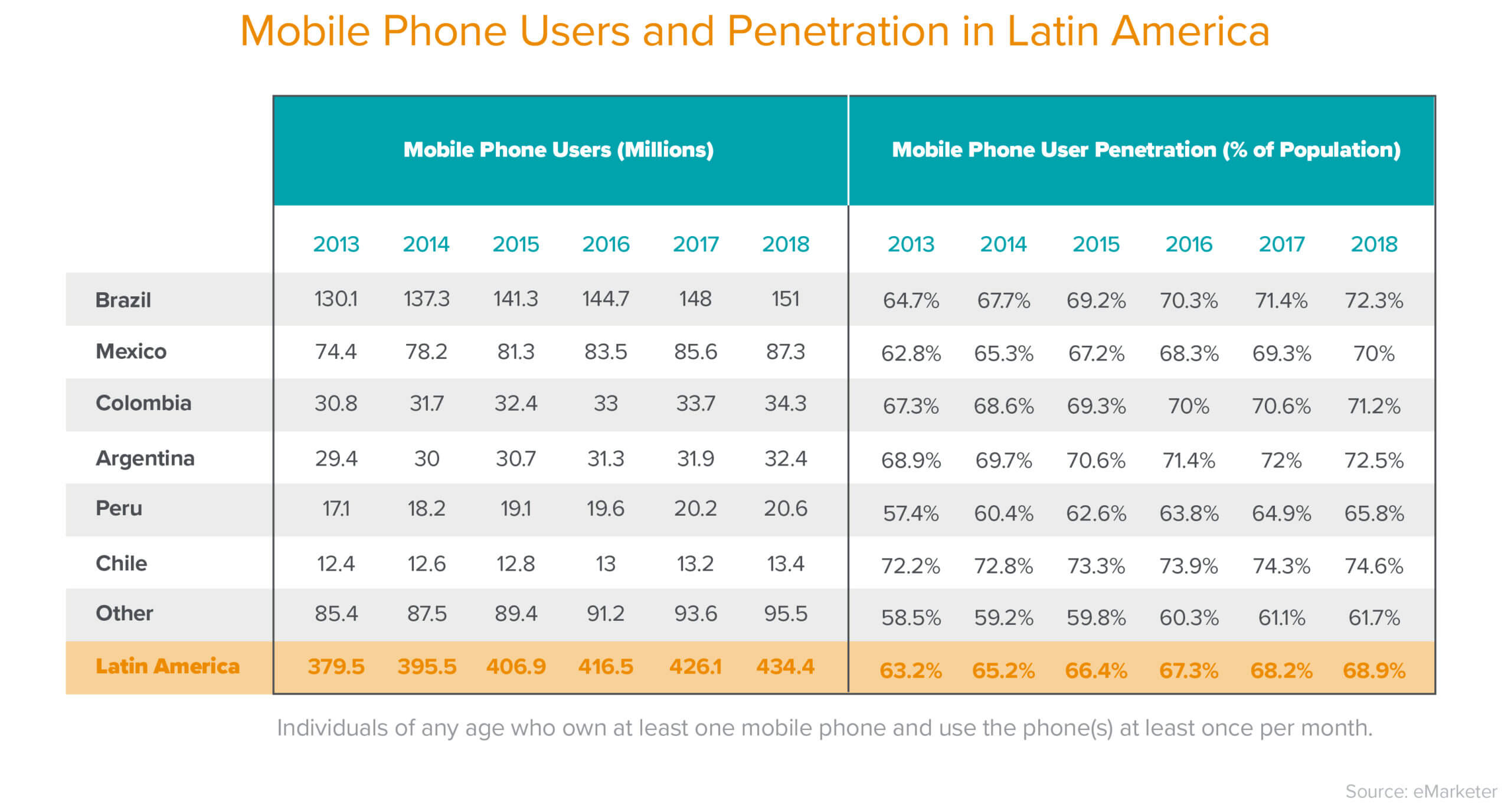

The status quo described above has remained largely unchanged for decades. But there’s reason to believe that changing consumer expectations, widespread smartphone adoption, and loosening regulation are creating an opening for financial innovation.

1. New consumer expectations and methods of distribution

In Mexico, 43 percent of the population is under the age of 25. This large, youthful consumer base expects their banking service to more closely mirror the consumers apps they use on a regular basis. Additionally, smartphone usage is becoming the norm, rather than the exception. Six years ago, only 35 percent of Mexicans had access to smartphones and internet penetration was below 50 percent; today, more than half of Mexicans have smartphones and 70 percent have internet access. That means many new customers have a potential bank branch in their pocket. In addition, Brazil is WhatsApp’s second biggest market, with 120 million users. The app is used throughout Latin America to text, shop, and pay.

2. Fintech-friendly regulation

Given that financial services are one of the most regulated industries worldwide, a pro-fintech government can significantly ease the creation and adoption of new companies. In 2018, Mexico passed the Fintech Law “Ley Fintech,” which created a framework for fintech companies to offer new products and operate legally under the same regulatory and supervisory requirements as traditional financial institutions. The government has three major priorities: to encourage the formalization of the economy, to increase financial inclusion, and to transition away from cash in an attempt to curb corruption and tax evasion. The Ley Fintech, which is set to take effect this year, encompasses regulation around mobile payments, digital wallets, crowdfunding, and cryptocurrencies. The law also offers new rules for open banking and APIs: legacy financial institutions will be required to allow other financial institutions to access their data to build better products for the Mexican consumer.

Brazil approved its Open Banking project in 2019 and the first phase went live in early 2021. Participation by large banks is mandatory, where each will provide APIs to enable third party developers to build applications with consumer data (shared with their consent).

Although Mexico was the first to pass such open fintech regulation in Latin America, other countries, such as Peru and Argentina, are expected to follow suit in the next few years. Chile, for one, announced a preliminary framework around open banking, as well as initial parameters around regulating crowdfunding, robo-advisors, and payment agents. Recent regulatory tailwinds provide a huge opportunity for fintechs to compete with the legacy financial institutions in Latin America.

3. COVID as an accelerant

The pandemic has had a profound impact on financial services around the world. But the COVID crisis has been a particular driver for fintech in Latin America, spurring innovation out of necessity. Though cash is still the predominant method of payment in Latin America, business shutdowns prompted the increased acceptance of digital and online payments. Many consumers tried out new financial products and apps, in lieu of visiting physical bank branches. Similarly, many businesses that once relied on foot traffic have begun offering online shopping, accepting card payments, and integrating with digital platforms. Ecommerce has seen double digit growth over the last few months. In Latin America, COVID has accelerated the demand for digital financial products by many years. The time for fintech is now.

4. The existence of real-time payment infrastructure

In the U.S., it still takes two days for funds to arrive, and the Fed has pushed the rollout of FedNow another 2+ years. In contrast, real-time payments have existed for over 10 years in Mexico. Brazil is in the process of rolling out its own version of real-time payments, called PIX. New fintechs are poised to take advantage of these efficient rails and make money work for consumers and businesses in the region.

The opportunities for fintech in Latin America

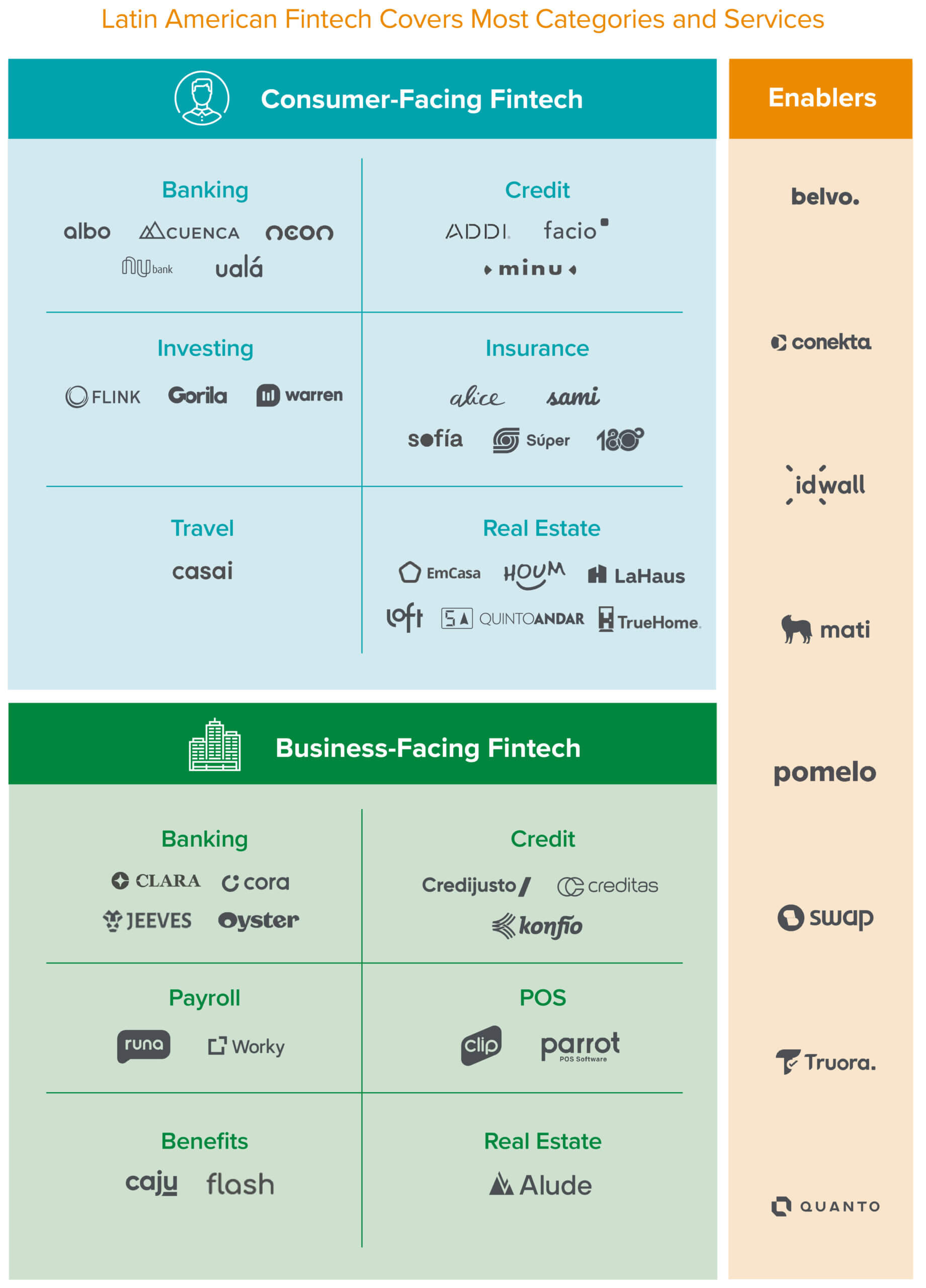

New full stack players

Today, as discussed, most Latin American countries are dominated by a handful of (mostly unloved) banks. As we’ve seen in other areas of the world, opportunity exists for new players to pick a customer segment and develop financial services tailored to those needs (e.g, Chime free banking and get your paycheck early, or HMBradley high APR savings, or more vertical specific players, like banks for landlords and property managers). Beyond banking products, opportunity exists for better investment platforms, as it’s still extremely hard to access the markets in many parts of the world, and more accessible, affordable insurance. Teams that will build these verticals will not only have insights into the product pain points of a specific demographic, but will also develop new distribution strategies to capture the latent demand ignored by current institutions.

Infrastructure

Talk to any of the existing or emerging “full stack” players above, and you’ll hear stories about how hard it was to build some layer of the infrastructure or how difficult it was to partner with a legacy partner. These “picks and shovels” opportunities are some of the most exciting in the region.

For example, fraud is a major challenge in the region. Card-not-present fraud is the highest in the world in Mexico, followed by Brazil. It’s estimated that approximately 20 percent of new user accounts created in Latin America are fraudulent, which puts the region at almost 2x the global level. Better services for KYC, KYB and AML, and identity in general are needed. Bank data is still underutilized and heavily protected by the financial institutions (although this should change in many countries with new fintech regulation), which is important for better credit decisions and risk models. Credit scores are also not widely used—many bureaus report negative effects only and do not have broad coverage. This complicates underwriting and results in higher rates for consumers. These are all promising areas for new fintechs to pursue and will be accelerants to more innovation in the region.

Business services

Not only are we seeing an increasing number of fintech companies, but there is explosive growth in the number of startups across many sectors in the region. All of these companies will need modern financial products: payroll, business credit cards, employee benefit solutions, and more. The rapid digitalization of business in the region also presents interesting accelearants to the need to modernize the way incumbent businesses operate and the tools that they need to compete. Pen and paper and on-prem solutions are being replaced by online and digital-first solutions to issue invoices, manage bookkeeping, and accept payments. We expect the trajectory for business services to be similar to what we saw in the U.S. over a decade ago. New, localized products and companies are poised to take advantage of these dynamics. The business customer base in Latin America is large, growing, and has high expectations for the modernization of banking; this presents a broad opportunity for startups.

Real estate

The concept of a Multiple Listing Service (MLS)—the best proxy to a single source of truth of real-estate listings in the U.S.—does not exist south of the border. In Latin America, real estate transactions are plagued with low transparency, lengthy processes, and very few financing options. Mortgage lending accounts for approximately 10 percent of Mexican GDP (around 10 percent in Brazil), which is much lower penetration than the 50 percent in the U.S. Not only is understanding what one’s property is worth nearly impossible (no Zillow!), but when trying to buy or sell a property there is no broker exclusivity and no platforms that might enable a buyer or seller to skip brokers entirely. This means that sellers are motivated to work with multiple selling brokers. Those brokers may list the same property on multiple listing sites, and brokers often aren’t financially motivated to push the process forward, given their lack of exclusivity. For buyers, this makes the process of purchasing a home challenging, as listings are often out of date (inventory is not available anymore). When we combine these dynamics with the fact that approximately 82 percent of Mexicans are more interested in buying than renting, startups like Loft are already looking to take advantage of this market and simplify the home buying, selling, and financing process.

Pan-LatAm expansion

Financial services companies are challenging to scale across borders—even more than companies in other sectors. In addition to having different cultural norms and languages, fintech companies must grapple with different regulation, preferred methods of payment, currencies, and infrastructure. To date, most companies to date have picked out a core market (preferably a large one), then set about proving that they can expand (usually making major changes to their business in the process to accommodate country differences). But as streamlined regulation and modern infrastructure eases these challenges, it’s possible that in the not too distant future, we will see more brands emerge that are able to cover many more of Latin America’s countries, opening up financial access for consumers and businesses alike.

In Latin America, success will come to teams with a deep understanding of local consumer or business needs, as well as the nuances of country-by-country infrastructure. Companies can accelerate their time-to-market by liberally applying fintech learnings and advances from around the world. We’ve been incredibly grateful to the companies and friends in the region that have helped us grasp these dynamics. We’re excited to support the next wave of Latin American fintech entrepreneurs!

-

Angela Strange is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on financial services, insurance, and B2B software (with AI).

-

Matthieu Hafemeister Matthieu Hafemeister is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz focused on early stage fintech investments. Matthieu joined the firm in 2017. He first spent time on the a16z Corporate Development team, working on late stage investments across verticals and helping portfolio companies raise downstream capit...

- Investing in FurtherAI

- Oil Wells vs. Pipelines: Two Strategies for Building AI Companies

- How Big Bank Fees Could Kill Fintech Competition (July 2025 Fintech Newsletter)

- How Will My Agent Pay for Things? (May 2025 Fintech Newsletter)

- What’s Working in AI, Rebuilding Core Banking (March 2025 Fintech Newsletter)