I’ll start by saying I’ve never even watched Law & Order, or Law & Order SVU for that matter. But I’m committed to out-punning and out-90s-pop-culture-referencing my partner Joe on all of our respective content. So I hope this resonates.

I’ll continue with a warning: the below is not a market map. Instead, I’d like to summarize my key learnings on Legal AI, having met many startups and software buyers focusing on it over the past 18 months. While I don’t expect these learnings to be revelatory, I’ve come to believe they are the forces–sometimes subtle and nuanced, other times glaringly obvious–underpinning the market structure as it exists today.

In-House Tools: Only a Fraction of Their Potential

While law firms command the lion’s share of prestige in the legal world, their clients (and their in-house teams) are the ultimate beneficiary of legal services; so let’s start there.

What’s the AI tool in-house lawyers have actually been using the most so far? Arguably, ChatGPT. It’s become the default base-case scenario: attorneys dabble with GPT for whatever tasks they can offload, and they ignore AI for everything they can’t. In other words, generative AI is often being used ad hoc – a quick contract tweak here, a snippet of research there. This low-barrier, general-purpose tool is filling the gap while dedicated “legal AI” software is still finding its footing.

Despite enthusiastic interest from in-house legal teams to invest in AI tooling, the actual capabilities in deployment today cover only a narrow slice of what’s possible. Broadly speaking, the tools that have gained traction so far are confined to things like better document redlining and faster legal research. Useful, yes, but it’s a fraction of what lawyers do. And there are a few problems with the status quo:

- Platform risk: Unless you own the word processor or email client where lawyers live, you’re stuck integrating into someone else’s platform – and those platforms are quickly rolling out AI features of their own.

- Low switching costs: These tools tend to be intuitively useful and quick to show value, but that also makes them easier to replace. If another product can do the same contract markup a bit better or cheaper, there’s little keeping customers from jumping ship.

- ChatGPT as competition: Let’s face it – for a lot of basic use cases, plain old ChatGPT itself is a viable alternative. It’s often good enough, constantly improving, and essentially free. If your shiny new legal AI tool doesn’t dramatically outperform a few well-crafted prompts in ChatGPT, lawyers might shrug and stick to the familiar base case.

Now, this isn’t a knock on the current set of in-house legal tools. Many have shown rapid traction, clearly tapping into pent-up demand. But in my view, they’re missing two key elements of the broader opportunity:

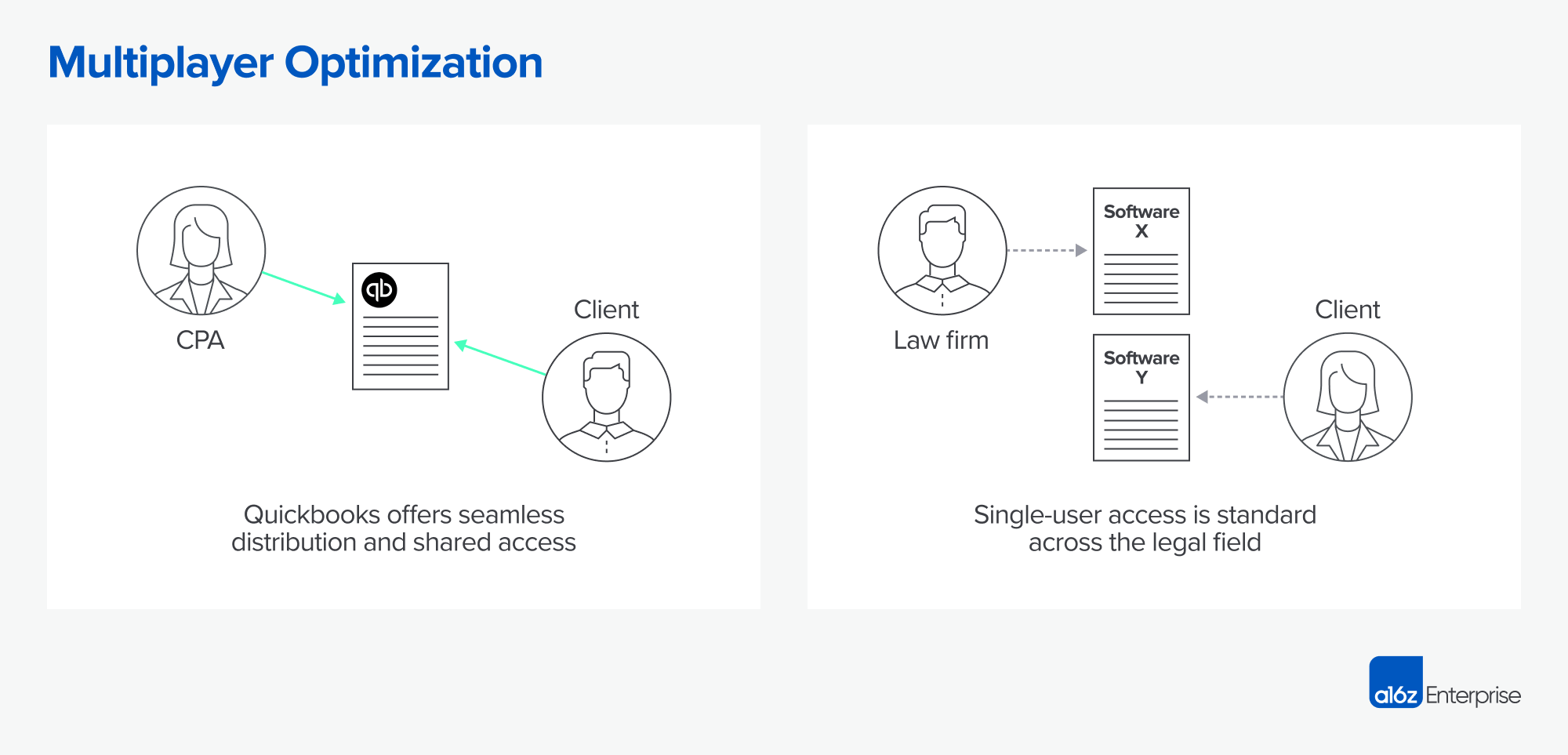

- Multiplayer Mode: None of these tools are truly multiplayer in the sense of connecting different organizations. Sure, they might be used by multiple people within a legal department, but where are the tools that bring together a company’s in-house team and their outside law firms on the same platform?Having studied the accounting software market, this feels like a missed opportunity. The big wins in accounting (think QuickBooks, Sage Intacct, Bill.com, etc.) massively benefited from accountants as key distribution nodes. Those products achieved multiplayer mode early: for example, a small business and its external CPA could share the same QuickBooks file, or a payer and vendor could transact together in Bill.com. That collaborative usage delivered real value and even created network effects – accounting firms would recommend the software to their clients, which in turn reinforced the accountants’ own workflows. I have yet to see a legal tool optimized for getting law firms and their corporate clients working together in one system. Could legal tech achieve a similar dynamic?

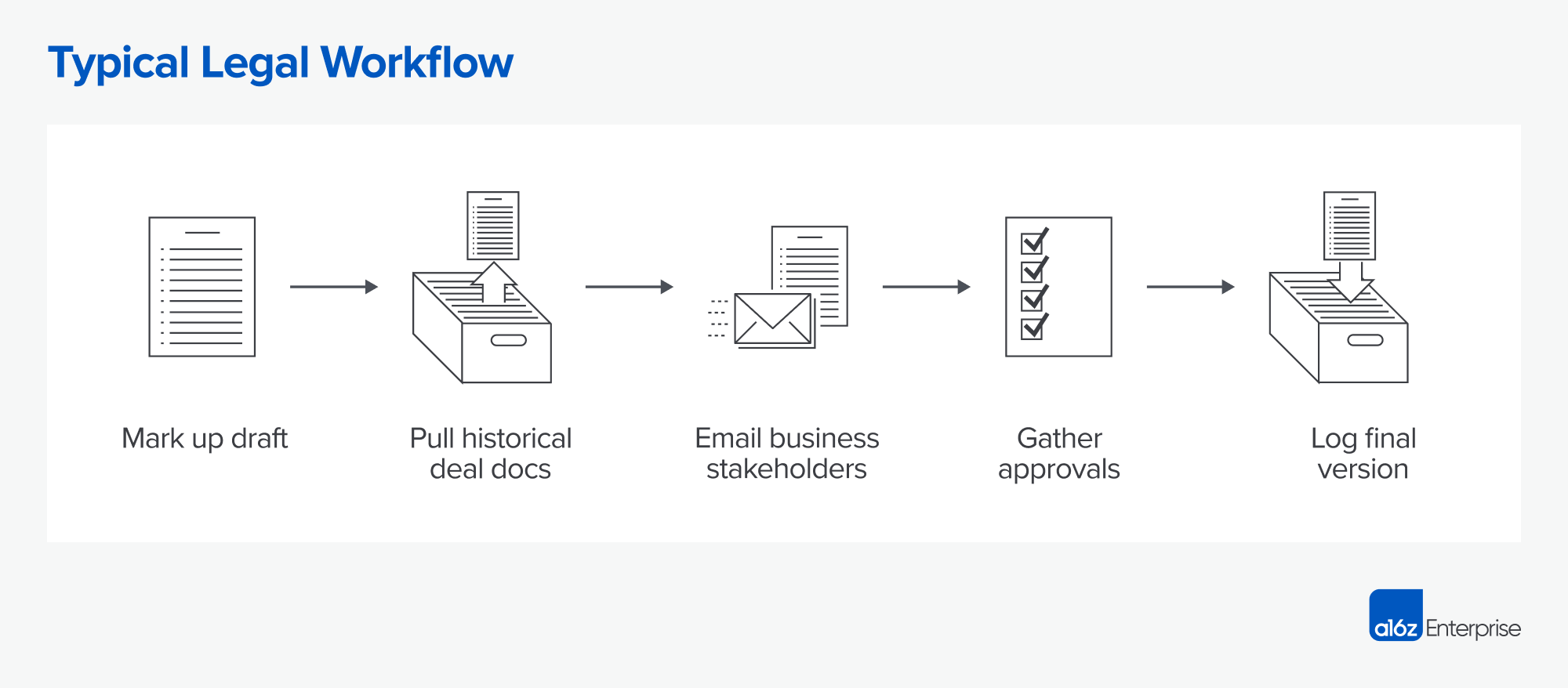

- Workflow Coverage: Redlining a contract or pulling up a few case-law references are handy capabilities, but they still feed into a larger workflow that remains mostly manual. After you mark up a draft, there’s often a slew of other steps: pulling historical deal documents from the Contract Lifecycle Management system (e.g. Ironclad) or file storage service (e.g. Box), emailing business stakeholders for input, gathering approvals, logging the final version into a repository, and so on. In other words, today’s AI tools address individual tasks, not the end-to-end process. If the goal is to actually automate the work, we may need something more akin to a Monday.com or Zapier for legal teams – a platform that orchestrates the entire sequence of legal work – rather than a collection of smart point solutions.

In-house legal departments are clearly eager for AI solutions, but so far they’ve gotten mostly point fixes. “Base case” is lawyers using ChatGPT on the side, and a handful of AI add-ons for contract review or research. So, what will it take to break out of that base case? Can we imagine legal AI products that achieve the kind of ubiquity and network effect that CFO-suite products did by connecting accountants with their clients? To explore that, we have to talk about something less flashy but absolutely critical: how these professionals make money. In other words, if you want to sell into the legal world (and perhaps even connect multiple parties in one product), you need to understand why business models are everything.

Business Model is Everything

Like other professional services, most legal work is billed hourly. At a typical “white shoe” law firm, the average associate might bill around $700 an hour and is expected to rack up roughly 2,000 hours per year. That yields about $1.4 million in revenue per associate. Now, consider the cost side: if you average out the Cravath-scale pay (widely known compensation data for big law), that associate costs the firm roughly $500k a year in salary and bonuses. Net net, they’re bringing in on the order of $900k in profit for the partner who oversees their work. With a common associate-to-partner ratio of 4:1, a single partner could be generating around $3.6 million in profit from their team of associates – and true rainmaking partners often leverage even larger teams and drive higher totals.

Why does this matter? Because, as the saying goes, show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome. A startup selling into a big law firm must understand the magic equation above that keeps the partnership model humming. If your product can introduce even more leverage into that equation – say, by enabling each partner to handle more matters and generate greater profit per partner – then it will practically sell itself. On the other hand, if your product’s promise is orthogonal or (heaven forbid) detrimental to the firm’s ability to bill and collect revenue, you’ll be swimming upstream against a very strong current. In plain terms: a time-saving tool that cuts hours out of a law firm’s day isn’t obviously a win for an hourly-billing firm. Increasing efficiency doesn’t delight a business that makes money by selling time.

When we invested in Eve, a big part of our thesis was that the plaintiff law model – which operates on contingency fees rather than hourly billing – would be a fertile ground for AI. In a contingency practice, efficiency directly equals more revenue: an AI that can automate hefty portions of case work means those lawyers can take on many more cases, win more settlements, and ultimately earn far more (since they get a percentage of the outcome). That’s a massive boon to their business model and earning potential. In contrast, try selling a pure “time-saving” product into a firm that bills by the hour… you can see the issue. Unless that firm is at capacity and can immediately backfill the saved hours with new billable work, you’re asking them to give up revenue.

Now, some might argue that eventually the big firms will be forced to adopt AI and pass along the efficiency to clients (perhaps moving to flat fees or other models under competitive pressure). The rebuttal sounds like this: “If Firm A uses AI to do the work in half the time, they could charge a lower price or take on twice as many matters; Firm B will have to follow suit or lose business, and the whole industry’s pricing will reset.” In theory, yes – but in reality, we haven’t seen this materialize at the top end of the market yet. The most prestigious firms are holding the line on the billable hour model, and clients are still willing to pay those rates, especially for high-stakes matters. The market perception remains “you get what you pay for.” When the risks are existential (bet-the-company litigations, critical M&A deals, etc.), clients aren’t clamoring for the cheapest lawyer – they want the best, and they expect to pay accordingly. Until a true external force (whether client demand or a new competitive entrant) compels a change, elite firms have little incentive to voluntarily slash their hours or rates using AI.

This is one reason I’m excited about startups tackling areas of law where the incentives do align for all parties involved. The plaintiff-side contingency model is one such area: everyone – the lawyers and their clients – benefits from tools that increase the chances of success and streamline the work. Likewise, certain high-volume corporate law workflows that are currently flat-fee or fixed-cost could be ripe for AI, because the law firms in those cases are motivated to improve their margins (by using less associate time) while the clients still pay a set price. In any case, the key is finding a wedge where using AI makes more money for the service provider or doesn’t threaten their revenue. If you can do that, you’re no longer fighting the tide – you’re riding a wave.

Is Brand the Only Current Source of Power in Legal AI?

If you’ve looked into the legal AI space, you’ve certainly heard of Harvey. And if you’re an investor or buyer in this market, chances are you’ve chatted with a Harvey user or at least a law firm that’s piloting it. Often those conversations go something like: “So, how are the lawyers at Big Firm X actually using Harvey day-to-day?” The answer, more often than not, is: “Well, they’re not really using it much… yet.” It might sound underwhelming – by many accounts, Harvey isn’t (at this stage) deeply embedded in most lawyers’ daily workflows. But guess what? That’s okay. Harvey is playing the long game in a vertical that runs on trust, reputation, and patience.

In many ways, Harvey has achieved something magical in a very short time: it’s become the default choice for AI at a significant number of prestigious law firms. The old adage in enterprise software is “nobody gets fired for buying IBM.” In legal AI today, nobody gets fired for buying Harvey. The product itself may not (yet) have a network effect – one lawyer using Harvey doesn’t inherently make another lawyer more effective, the way one new user might improve a social network or a file-sharing platform. But there is a compounding competitive advantage at play here: brand. Each additional white-shoe firm that publicly partners with Harvey makes the next firm that much more likely to jump on board, whether out of FOMO, competitive pressure, or simply the validation that “all our peers are doing it.” Legal is a tight-knit industry; CLOs and innovation teams swap notes, partners at different firms talk at conferences, and everyone wants to know what everyone else is trying. Harvey’s strategy has leveraged this phenomenally well.

Harvey recognized early on that a bottoms-up, product-led growth motion would be nearly impossible in the big firm market. An individual associate or even a partner can’t just start shoving sensitive client data into a new AI tool without the firm’s blessing – not at a reputable firm with strict confidentiality and IT rules. So Harvey went top-down: from the early days, they sought enterprise-wide agreements with firms, getting buy-in from a coalition of stakeholders. This often meant involving the firm’s innovation committee, IT and knowledge management teams, and some forward-thinking partners who could champion the cause. By landing the whole firm (or a large practice group) in one go, Harvey sidestepped the need to win over end-users one by one at the outset.

The result is that Harvey now sits inside a lot of major firms, perhaps not heavily used yet, but very much there and available. And Harvey has time – a luxury in startup land! Even if active usage is low in year one, the firm has signed on and is unlikely to rip out the platform, because everyone agrees that the legal profession stands to benefit massively from AI in the long run (“text in, text out” workflows are perfect for AI). These firms want to be prepared, and they’ve essentially placed a bet on Harvey as their partner for that journey.

But if There Were Network Effects, They Might Look Like…

We hear a lot of pitches about how each new client supposedly makes the overall AI smarter for everyone (via model fine-tuning, feedback loops, etc.). In practice, though, true data network effects in legal are extremely limited by design. Law firms guard their data like treasure, and rightly so – no firm is going to agree to a vendor using their confidential work product to go train some model that a competitor firm down the street will also use. The idea that “our model learns from each lawyer’s interactions and that makes it better for all lawyers” hits a wall when those interactions involve highly sensitive documents and facts that cannot leak outside. So, at least for now, each large client’s data has to remain siloed. Most legal AI companies are pre-training on public data (SEC filings, case law, legislation, etc.), which means everyone’s essentially drawing from the same well to start. Sure, you can fine-tune on a firm’s internal data to make the product better for that firm, but those gains won’t directly transfer to other clients. In short, it’s hard to build a traditional data moat or cross-client network effect in this industry under current conditions.

What is possible, however, are positive feedback loops within a product’s usage at one client, or within a particular subvertical. This is a slightly different concept from a classic network effect, but it’s important. Let’s look at Eve again. Eve’s platform focuses on plaintiff-side litigation, and it exhibits a kind of flywheel effect: the more case work Eve helps a law firm complete (and the better outcomes those cases achieve), the more the system learns from those successes. For example, it can better assess new case intakes over time – identifying patterns in what makes a case likely to win or settle favorably – and thereby help the firm be smarter about which cases to take on. Those improvements reinforce Eve’s value throughout the case lifecycle for that firm. While Eve isn’t sharing data across different law firms, it is continuously learning within each firm’s environment and, at a higher level, improving its domain-specific models on patterns that generalize (like how certain fact patterns correlate with outcomes in, say, personal injury cases). This kind of self-reinforcement can create a competitive edge and strong customer loyalty, even if it’s not a viral user-growth loop like we see in consumer apps.

In sum, Harvey’s success so far highlights that brand and trust can function like network effects in legal tech: being the name everyone knows (and no one gets fired for buying) is incredibly powerful. And while no product has a Facebook-style network effect in this space (nor is one likely, given data silos), the best companies are finding ways to create stickiness and improvement over time – whether through strategic GTM moves or through iterative learning in their niche.

Conclusion

The legal AI boom is real – it feels like every day I hear about another sharp team building a product for some corner of this enormous market. The excitement (and hype) is understandable: few industries deal so natively in text, documents, and knowledge as law does, and thus few seem as ripe for AI-driven transformation. But not every idea will stick, and not every startup will survive the gauntlet of law firm and legal department adoption. From my front-row seat, what separates the signal from the noise are a few key things, which are the primary drivers of where I’m most excited to invest:

- Solving the Incentive Puzzle: The most promising companies deliver clear ROI in the context of their customers’ business model. They’re not fighting the billable hour – they’re aligned with how users make money (or save it) in a big way. That’s why we’re particularly drawn to companies tackling contingency-based models, high-volume fixed-fee work, and automated intake/orchestration for firms looking to scale.

- Brand and Trust: In a conservative, tight-knit industry, being the credible, “safe” choice can become a moat. We’re interested in companies that either have a real shot at becoming the default AI partner for a large segment of the legal market, or are laser-focused on nailing distribution within a single tight-knit subsegment—not just chasing logos.

- Beyond Point Solutions: Finally, we’re looking at teams rethinking legal workflows, not just tools. The most compelling legal AI companies are building products that create positive feedback loops, enable multiplayer collaboration, or own the end-to-end workflow, rather than just inserting an AI feature into an existing task.

The legal profession is often portrayed as slow to change, but we’re seeing the early signs of a real transformation. From in-house departments looking to automate grunt work, to law firms exploring how to augment their armies of associates, to plaintiff attorneys scaling up their case loads – everyone knows change is coming. The base case (ad hoc ChatGPT usage and a few AI point tools) is only the beginning. The escape velocity will come from cracking the go-to-market code, aligning with incentives, and building products that get better the more people rely on them. Do that, and you won’t just have a legal AI tool – you’ll have a platform with staying power in an industry that’s ready to evolve. Case closed.