This first appeared in the monthly a16z fintech newsletter. Subscribe to stay on top of the latest fintech news.

2023: A Year for Fintech M&A?

Marc AndruskoWe’re only one month into 2023, and fintech mergers and acquisitions of all shapes and sizes are practically being announced daily. We’ve got public companies buying startups (Fidelity acquiring Shoobx, Pagaya acquiring Darwin Homes), and startups buying other startups (Deel acquiring Capbase), with motivations that likely range across all three types of M&A, as described by my partner Alex Rampell:

As the macro environment continues to tighten and investors focus more on efficiency and less on growth (at least relative to recent years), startups will continue to face challenging fundraising conditions (particularly those that raised at high prices relative to their traction). Unprofitable companies without sufficient runway or an extremely compelling growth story will soon find themselves evaluating their options, and we expect M&A will surely be top of mind for them.

With this in mind, now is an opportune time to revisit another Alex Rampell-ism: what will come first, incumbents getting innovation, or startups getting distribution?

In the prolific bull market that spanned from the end of the global financial crisis (late 2009) to the onset of the pandemic (early 2020), we enjoyed record-low interest rates, vast amounts of liquidity, strong economic growth, and an S&P 500 that returned on average 16% a year. As Oaktree Capital Management Cofounder Howard Marks describes it, “the paltry yields on safe investments drove investors to buy riskier assets,” which led to a heightened interest in venture capital and startups. In that environment, startups were well-positioned to chase distribution: they had free-flowing venture dollars subsidizing expensive customer acquisition through any number of paid channels. Growth reigned supreme, and relative to any other time in recent memory, distribution was not as daunting of a concept for any fledgling company with a slick product to pursue. The name of the game was brand building and marketing, and new digital attackers were eager to steal the tens of millions of customers the incumbent ecosystem enjoyed.

That was then, however, and this is now. Due to the tightening budget situation described above, today’s startups may be harder-pressed to manufacture explosive growth in a short period of time. Yet that is exactly what they will need to do in order to compete with the larger firms, who enjoy massive economies of scale, allowing them to see high returns on capital.

We believe now is a ripe time for both sides of the equation to consider partnerships and M&A for the following reasons:

- Incumbents can accelerate their path to innovation. A 2023 Financial Brand survey of financial institutions found that respondents ranked improving the digital experience for consumers, enhancing data and analytics capabilities, and reducing operating costs as their top three strategic priorities. Fintech startups, full of strong technical talent and lean operations, can provide extremely viable solutions to all of these issues.

- Startups can accelerate distribution. Founders committed to high-impact missions on a national or global scale can quickly get their products in front of millions of customers due to the huge captive audience incumbents enjoy.

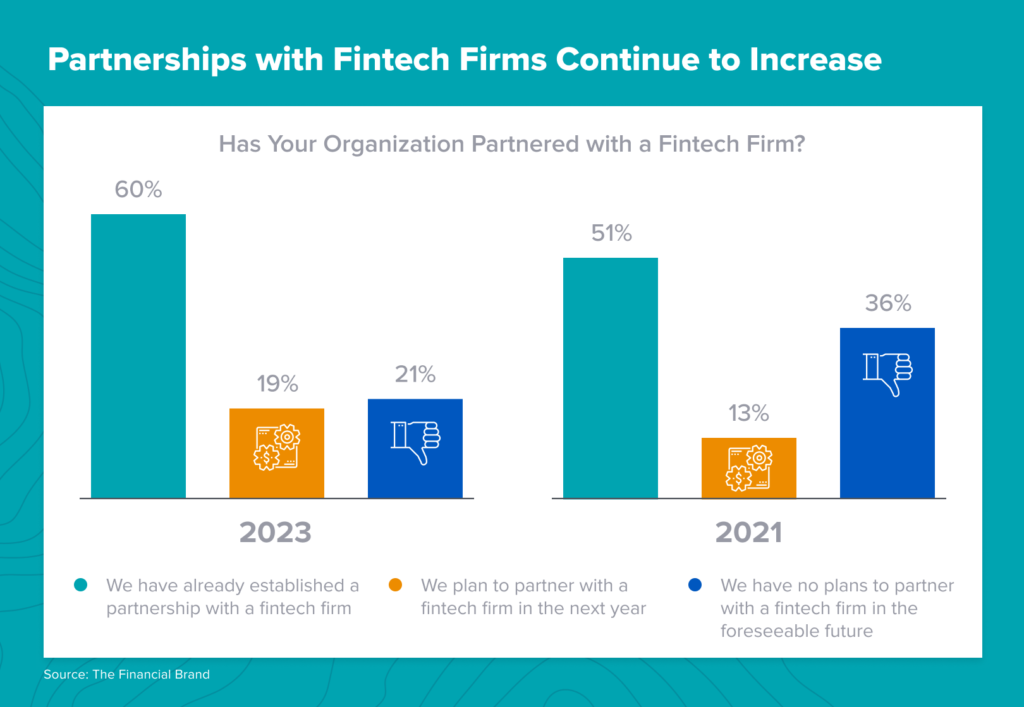

- Both sides are more eager than ever to work together. The same Financial Brand survey identifies that more and more traditional financial services firms have tested the waters with fintech partnerships. While procurement and compliance will continue to be obstacles in velocity, the stage is set for further collaboration.

Plenty has been written about what life for startups will look like in this new market environment. We hope both incumbents and startups will consider joining forces to jointly accomplish their most pressing goals. If the pace of deal activity in the first month of the year is any indication of what’s to come, 2023 could be a big year for fintech M&A.

How Should Founders Think About M&A Opportunities?

Melissa Wasser, JJ YuGiven the drought in the equity markets and the few-and-far-away mentions of SPACs and IPOs, as our colleague Marc details above, we would like (and hope!) to assume a great number of conversations are happening behind the scenes around consolidation.

We believe it’s never too early for founders to begin talking to key strategic partners. Not only do incumbents have access to massive distribution, which can super-charge your product if you enter into a partnership, but in some cases, these conversations can directly lead to a big acquisition down the road.

Just take a look at Visa’s M&A history. Over the past five years, Visa has acquired eight companies. Of those eight companies, Visa was either already an existing investor in, or had a prior relationship with at least five of them. For example, in 2021, Visa acquired Currencycloud, a B2B cross-border infrastructure solution, for £700 million. Visa was not only a customer, but also an investor in Currencycloud’s Series E financing in 2020. TrialPay, one of the startups founded by our General Partner Alex Rampell, also had a strategic partnership with Visa that included a license agreement in 2014 and an investment in 2011, before it was ultimately acquired in 2015. As another example, Intuit often begins relationships with startups via a small investment or partnership, which has led to multiple acquisitions (SeedFi, OneSaas, and Tradegecko are all examples of this).

As founders think about potential strategic relationships, our team of in-house experts and ex-operators recommend that they come up with roughly five strategic investors (or potential acquirers) and get to know key decision makers with P&L responsibility at these organizations. It’s important that these people control some form of product or capital allocation roadmap and have the will to sponsor a potential deal; meeting the corporate development person is unlikely to result in your company being bought. Also, keep these relationships warm and decide with your senior team what the best cadence is for staying top of mind, this will likely be different for each startup. Only speaking to these connections once every few years is too infrequent and unlikely to result in anything material happening. In general, founders should ideally spend 5-10% of their time just focused on capital raising and building relationships (inclusive of prospective M&A) as a background process.

As 2023 progresses, founders should assess for themselves the current market and their ability to raise capital. Remember, finding a corporate investor could not only provide funding, but also a path toward an eventual exit. Near term, it could also be coupled with a partnership to drive additional users, revenue, and growth. We know most founders did not start a company to sell it, but we believe in keeping the option open and allowing multiple paths for those who are building.

- Managing Your Facility and Tools to Automate the Process David Haber, Melissa Wasser, and JJ Yu

- It’s Time to Raise Your Debt Facility: Execution Tactics for Founders David Haber, Melissa Wasser, and JJ Yu

- The 16 Commandments of Raising Equity in a Challenging Market Manas Punhani, JJ Yu, Melissa Wasser, and Peter Blackwood

- Negotiating Your First Warehouse Facility: Trade-offs Across Terms David Haber, Melissa Wasser, and JJ Yu

- Managing Your Facility and Tools to Automate the Process David Haber, Melissa Wasser, and JJ Yu

- It’s Time to Raise Your Debt Facility: Execution Tactics for Founders David Haber, Melissa Wasser, and JJ Yu

- The 16 Commandments of Raising Equity in a Challenging Market Manas Punhani, JJ Yu, Melissa Wasser, and Peter Blackwood

- Negotiating Your First Warehouse Facility: Trade-offs Across Terms David Haber, Melissa Wasser, and JJ Yu

Rising Rates Have SMBs Feeling the Crunch

Seema AmbleWhen the Fed started raising interest rates in 2022, both consumers and small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) started to feel the impact of the move. This year, however, SMBs are likely to feel more of the financial burden from rate increases as the follow-on effects to the cost of doing business flow through—creating a potential opening for fintech software companies.

To start, let’s review the specific effects of rate increases on SMBs. As interest rates go up, interest expenses for SMBs also increase. For example, loan products, from credit cards to working capital facilities, generally have variable rates that adjust as interest rates increase. In today’s environment, this is coupled with rising expenses on everything from materials to rent—expenses that were triggered by last year’s increased rates, but will only start to be reflected this year, as price changes take time to take effect (e.g., due to menu costs, companies put off the operational cost of changing pricing). Also feeling the crunch are suppliers to these SMBs, who want to get paid faster, and the SMBs’ customers, who want to extend their credit terms, given both parties will potentially be in similarly tighter cash positions.

At the same time, lending from traditional sources—i.e., banks—has been contracting. The Kansas Fed reported earlier this month that by Q3 2022, banks had already started to tighten their underwriting standards and were pulling back their loan volumes to adjust to the heightened perceived risk of SMBs missing payments and going out of business. But they also don’t want to offer rates that look unfriendly to customers. This compounds the issues SMBs already face in finding credit due to their higher risk profiles, heterogeneity of business models, and smaller profits, which make them less attractive as clients to banks. Applying for credit through banks often takes a few weeks, paperwork, and potentially several bank visits. We’ve also seen a number of startups withdraw from the traditional SMB market (e.g., Brex). The online lenders are also going to face higher delinquencies, leading them to pull back as well. Together, these increasing costs from rate increases and lower access to credit are creating stress for SMBs.

This cash flow crunch creates an opportunity for fintech companies. First of all, since credit is harder to get, cash has become the focus. As a result, cash flow management tools have never been more valuable—specifically, tools that provide insight into cash, such as predictions around who pays on time, how long the average working capital cycle is, when payment typically happens, and the terms around current credit cards or loans. This visibility is currently missing for almost all SMBs, especially since they likely do not have a finance team the way a bigger company might. In addition to analytics, SMBs need access to credit more than ever to help smooth their cash flow issues.

Rather than being standalone offerings, these cash flow management tools should live within broader software platforms that carry data on payment flows and the health of the business overall (e.g., B2B payments platforms, vertical software, or B2B marketplaces). The ongoing data these platforms capture gives a dynamic look at the business that can assist with underwriting, one a traditional lender cannot capture. Further, these platforms capture benchmarking data against a peer set that is valuable to both the customer and towards underwriting. This data can be especially rich if verticalized and if it picks up the specific metrics that matter for an industry. While this level of visibility always has value to SMBs, it’s true now more than ever and these fintech offerings can be a helpful product for these platforms to attract customers.

- Investing in Lio Seema Amble, James da Costa, Eric Zhou, and Brian Roberts

- Need for Speed in AI Sales: AI Doesn’t Just Change What You Sell. It Also Changes How You Sell It. Seema Amble and James da Costa

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable Seema Amble, Joe Schmidt, and Brian Roberts

- The AI Application Spending Report: Where Startup Dollars Really Go Olivia Moore, Marc Andrusko, and Seema Amble

- The Rise of Computer Use and Agentic Coworkers Eric Zhou, Yoko Li, Seema Amble, and Jennifer Li

Regulatory Crackdowns Start to Push Compliance Spend Up

Joe SchmidtAs we wrote in our predictions for 2023, compliance is going to be a major focus area for fintech companies this year—and regulators are already on a roll. Within days of starting the new year, the New York State Department of Financial Services (NYSDFS) announced it had reached a $100 million settlement with Coinbase for violating anti-money laundering laws. While this may seem like a slap on the wrist when compared to some larger fines—such as Wells Fargo’s $3.7 billion fine at the end of 2022 for legal violations across several of its product lines—Coinbase, interestingly, is required to spend $50 million, or half of the settlement, on improving its compliance program.

This is intriguing for a few reasons. First, it’s worth noting that the infractions Coinbase has been penalized for happened over a two-year period in 2018 and 2019, but were only discovered during inspections that took place in 2020 and 2021. This underlines the fact that complying with regulatory requirements is one area where financial services startups should avoid moving fast and breaking things, as your transgressions will likely be found out. Second, the NYSDFS was less concerned with the infractions and more concerned with how poor Coinbase’s systems and processes were around compliance—notably know your customer (KYC), transaction monitoring, and suspicious activity reports (SARs). Third, given how important these three areas are to many types of fintech businesses, from banking to brokerage, fintech startups should look at Coinbase’s case as a warning shot of what’s to come if appropriate compliance steps aren’t taken.

While there is no shortage of reasons for why compliance software is necessary, the fact that regulators are actively requiring financial services companies to spend money on improving their compliance programs will only increase the urgency for and adoption of new software in this space.

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable Seema Amble, Joe Schmidt, and Brian Roberts

- Investing in FurtherAI Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- Oil Wells vs. Pipelines: Two Strategies for Building AI Companies Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- From Demos to Deals: Insights for Building in Enterprise AI Kimberly Tan, Joe Schmidt, Marc Andrusko, and Olivia Moore

- Trading Margin for Moat: Why the Forward Deployed Engineer Is the Hottest Job in Startups Joe Schmidt