In the early days of the energy industry, fortunes were made in two very different ways. Oil wells generated massive profits by tapping a single rich deposit. Pipelines, the steel arteries that moved oil between wells and customers, created value by carrying flow at scale. One strategy was about owning the repository, the other about connecting it. Both produced enormous returns.

AI founders face the same choice: drill an “oil well” by going deep into a single workflow until you own the system of record, or build a “pipeline” that moves data and automates judgment-heavy work across many workflows. Both can generate venture-scale outcomes – they just require different approaches to building, selling, and compounding advantage.

Since the beginning of enterprise software, the most lucrative B2B companies have become a system of record. By becoming the system of record, they lock in customers, create workflow dependency, and build durable moats.

AI accelerates this playbook. Unlike legacy systems built 30+ years ago, startups today can deliver order-of-magnitude improvements that make incumbents look instantly vulnerable. With boards and management teams primed to “buy AI,” these startups are shortening sales cycles and opening replacement opportunities that previously didn’t exist.

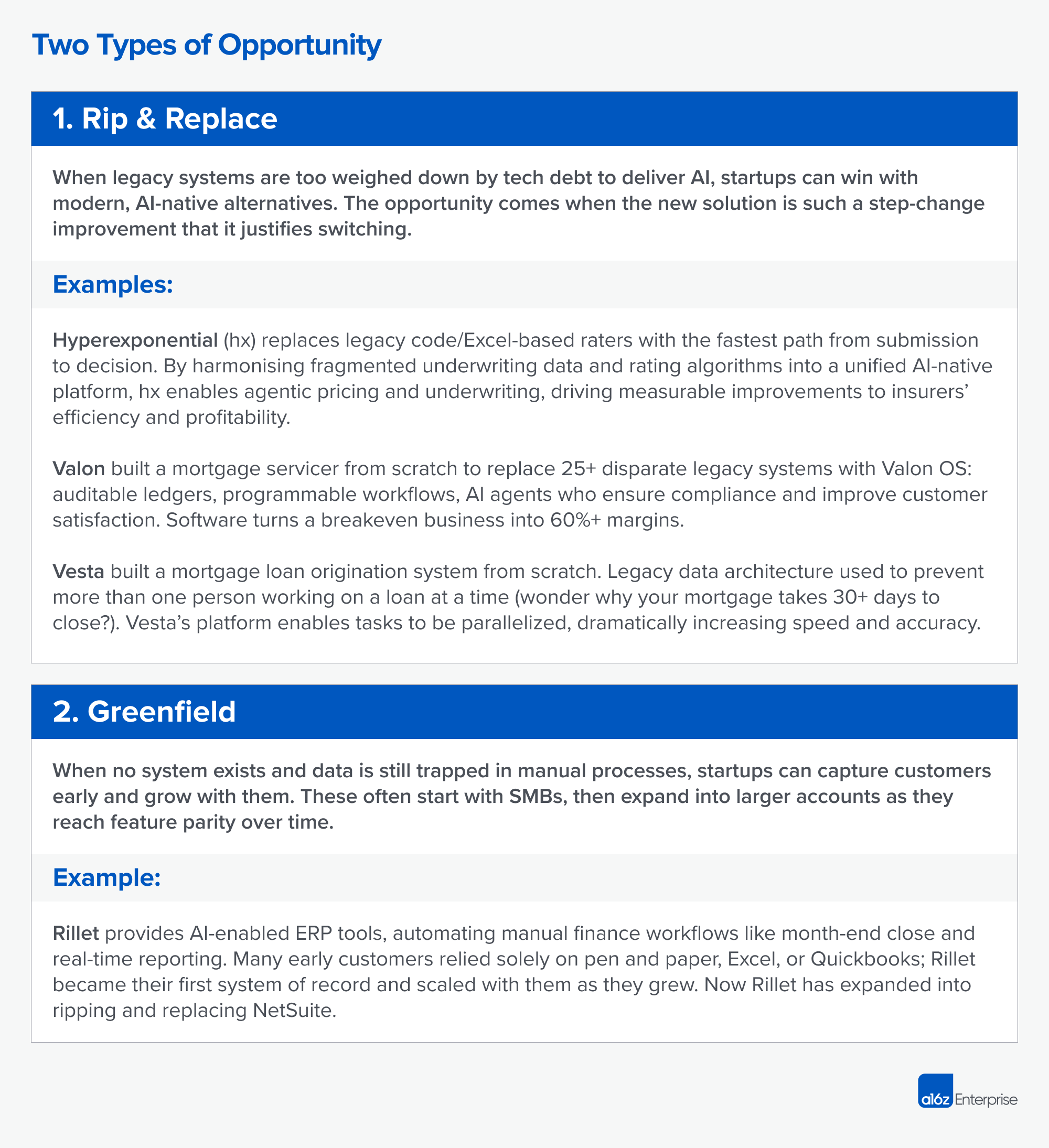

The oil well approach works best where unstructured data, or data residing in disparate systems, when organized, unlocks significant improvements in customer experience. We’re seeing this approach fall into two types of opportunity:

Defensibility for these companies is structural. Once they own the core data model, they can build applications no other provider can, leading to workflow dependency and compounding switching costs. Oil wells take longer to drill, but once established, they create deep, durable moats.

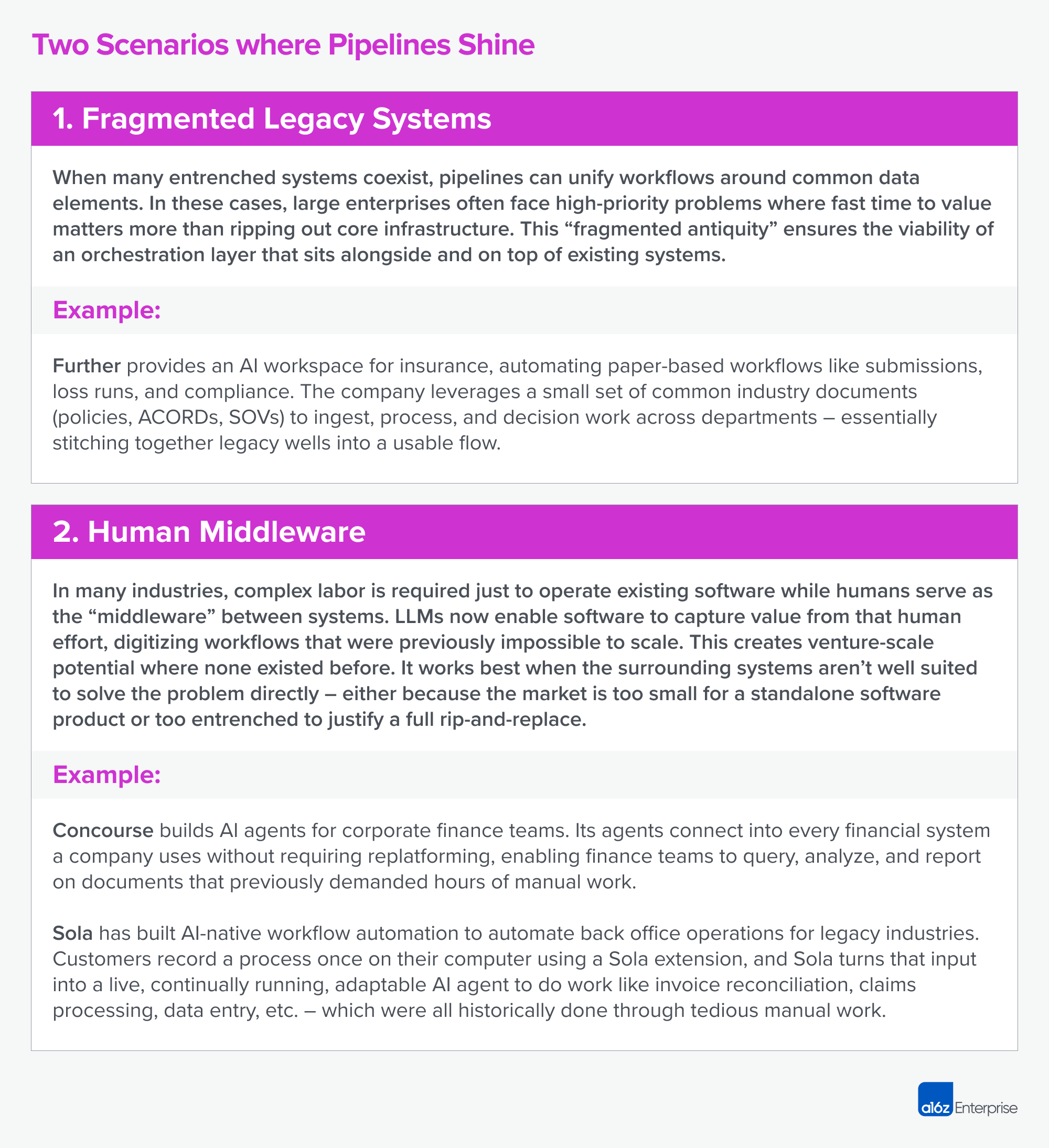

Conventional wisdom said building around systems of record was just a feature, not a business. And in some cases that’s still true – incumbents can absorb certain orchestration tools as they grow. But many legacy wells are too embedded or compliance-heavy to change quickly, while the demand for AI-driven efficiency is higher than ever. AI expands the opportunity further: agents can now take on work in markets that were previously too small to justify a solution, or too irregular and unstructured to automate.

Rather than replacing core systems, pipelines automate the glue work humans do between systems including processing unstructured information, making context-dependent decisions, and executing across workflows and departments. These are tasks typically reserved for humans, which opens up large opportunities to solve problems software historically ignored.

Unlike oil wells, pipelines don’t require customers to rip and replace. They gain traction quickly by reducing human effort and stitching together siloed systems. Over time, each new workflow reinforces the platform, creating compounding stickiness.

Why Customers Don’t Have to Choose

While startups need to pick a strategy, customers don’t. In complex enterprises, oil wells and pipelines often coexist: one part of the business may need a new system of record, while another just wants lightweight automations to bridge old systems or reduce the human labor required to run them.

Choosing With Intention

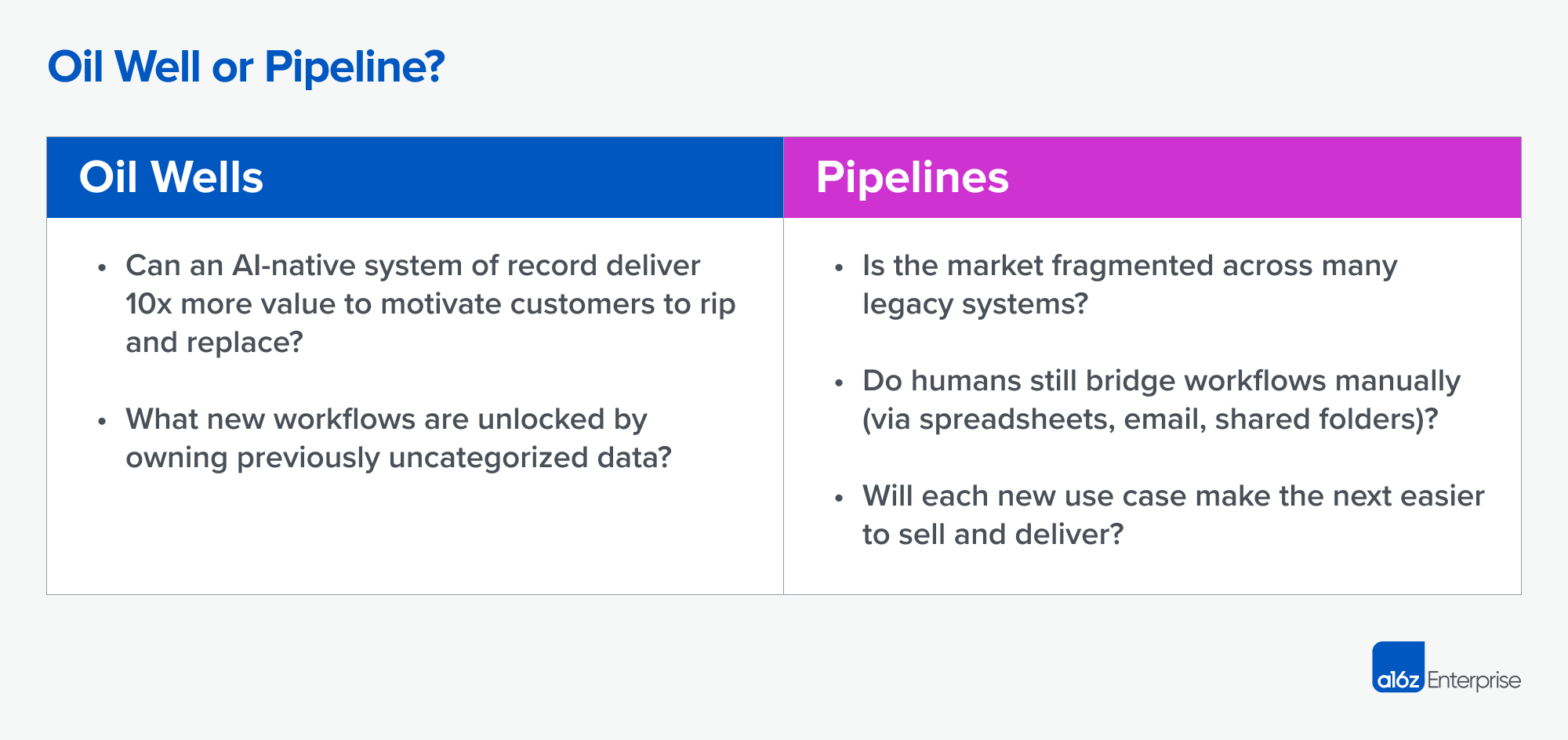

Both strategies can create massive companies, but which one works depends on the shape of the market. Oil wells make sense when the opportunity lies in owning critical data and unlocking entirely new workflows from it. Pipelines make sense when markets are too fragmented or labor-intensive for a full rip-and-replace, but where AI can capture value by automating judgment-heavy work. So although customers don’t need to choose, founders do.

The right model depends on the market. These are the questions that reveal it:

The Bottom Line

Oil wells and pipelines aren’t competing metaphors. They’re complementary strategies for building enduring AI companies. Wells win by owning the ground truth; pipelines win by orchestrating the work around it. Both can be massive. What matters is not trying to do both at once, but knowing which game you’re playing and winning.

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable

- Investing in FurtherAI

- How Big Bank Fees Could Kill Fintech Competition (July 2025 Fintech Newsletter)

- From Demos to Deals: Insights for Building in Enterprise AI

- Trading Margin for Moat: Why the Forward Deployed Engineer Is the Hottest Job in Startups