“Imagine a widely used and expensive prescription drug that claimed to make us beautiful but didn’t. Instead the drug had frequent, serious side effects: making us stupid, degrading the quality and credibility of our communication, turning us into bores, wasting our colleagues’ time. These side effects, and the resulting unsatisfactory cost/benefit ratio, would rightly lead to a worldwide product recall.”

-Edward Tufte, The Cognitive Style of Powerpoint

I’m not sure I’ve ever seen a company’s Seed Round pitch deck include a quote from its subject medium’s greatest hater. But, there you have it. Succinctly expressed, indisputably true: “PowerPoint makes us dumb.” And in the five years since founding Gamma, Grant, James and Jon have done something I didn’t think possible: they’ve actually made progress on the root of the problem. They built “PowerPoint but it makes you smart.” And higher-agency, too!

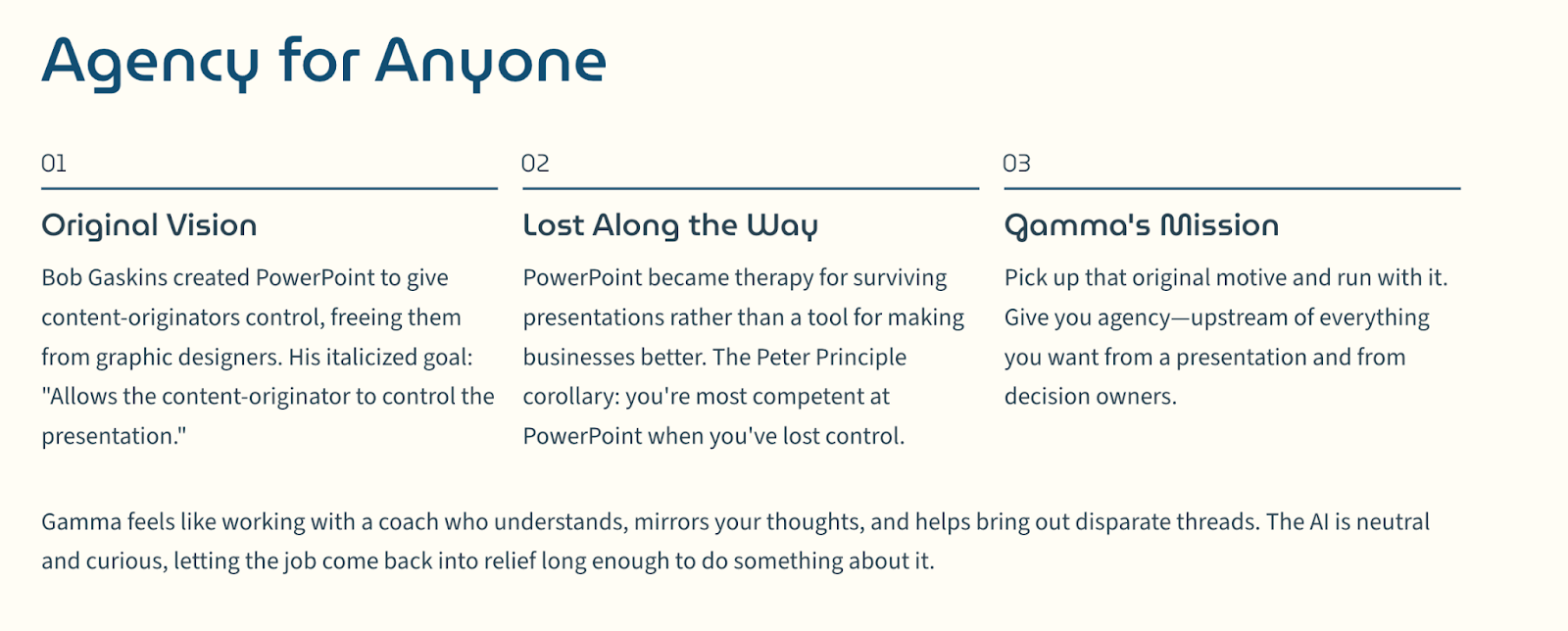

Following yesterday’s announcement that Gamma raised their Series B led by a16z, I want to share how much I love what they’ve got cooking. Gamma is a genuine attempt to improve our thinking with better defaults, and break us out of patterns of learned helplessness:

- The trope criticism that AI turns us into lazy, linear thinkers was already true about PowerPoint; whereas the prompt box is actually a gift for lateral thinking.

- PowerPoint’s real job-to-be-done has always been, “Help the presenter survive the presentation.” Our tools should aim higher than this!

- The original vision of PowerPoint’s founder was “Putting the content-originator in control.” We’re getting there with Gamma, four decades and billions of slides later.

In a world where agency is everything, you don’t want PowerPoint to be your therapist. You want Gamma to be your coach.

Word and Excel are tools, PowerPoint is something else

PowerPoint has always been a little different from its “founding generation of desktop software” peers. Unlike Word, Excel or Outlook, we don’t think of PowerPoint as a tool, exactly; that’s not what it is. Ian Parker wrote in The New Yorker in 2001: “PowerPoint is more like a suit of clothes, or a car, or plastic surgery. You take it out with you. You are judged by it—you insist on being judged by it. It is by definition a social instrument.”

Everyone reading this, I assume, has used PowerPoint plenty in their lives (or lightweight clones like Google Slides). So you’ve been there: starting with a blank slide, facing your hero’s journey. And PowerPoint does come to your assistance, sort of, in this situation.

But it doesn’t exactly help you communicate something (you do that in Word, or Excel); or coordinate something (you do that in Outlook, or nowadays Slack). PowerPoint’s job is simply to help you survive the presentation. It helps you cope: “You have no real power over this situation, yet you represent it.” And the experience of making slides, one after another, flows from that initial job-to-be-done of divide-and-conquering the presentation into individually survivable sections, slides, and bullet points.

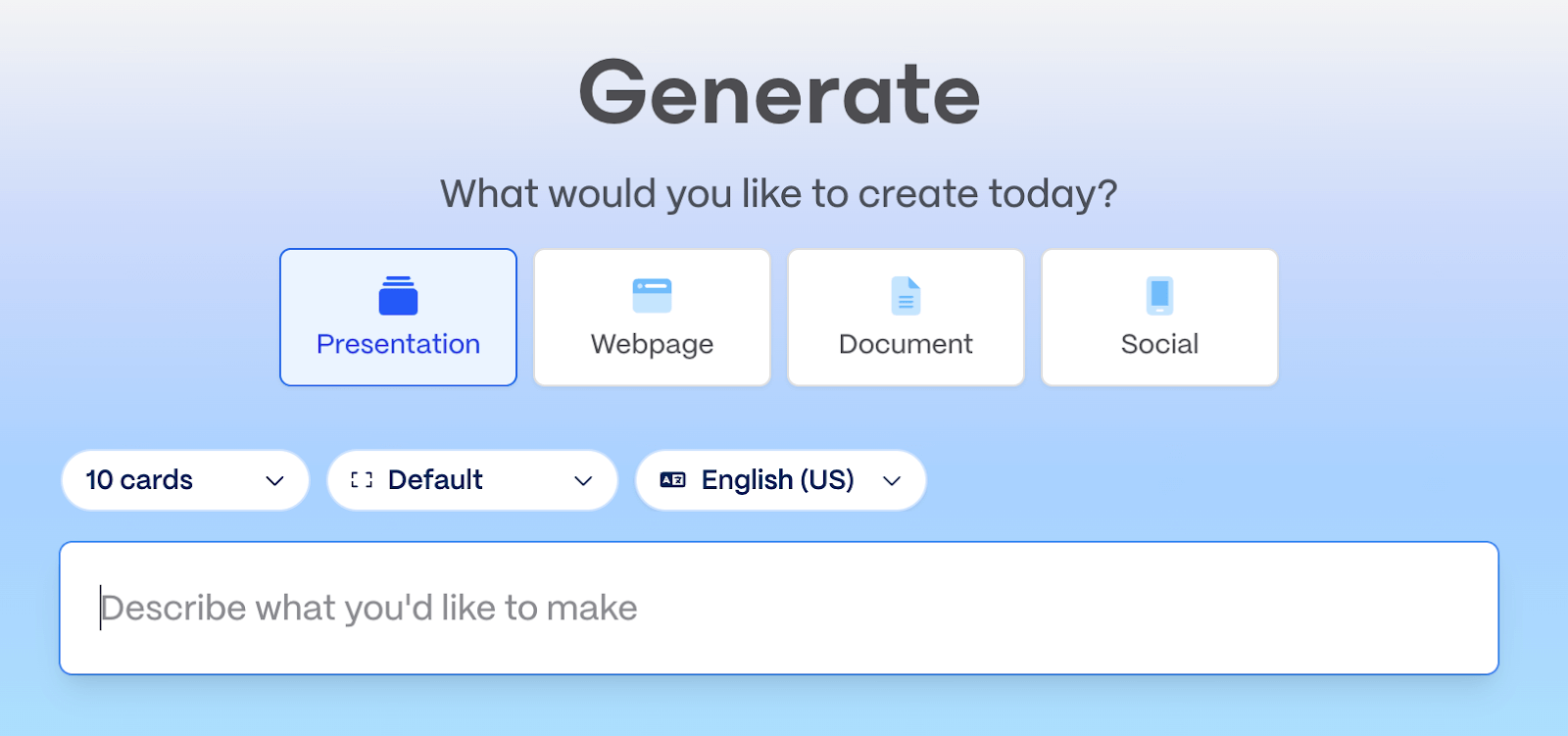

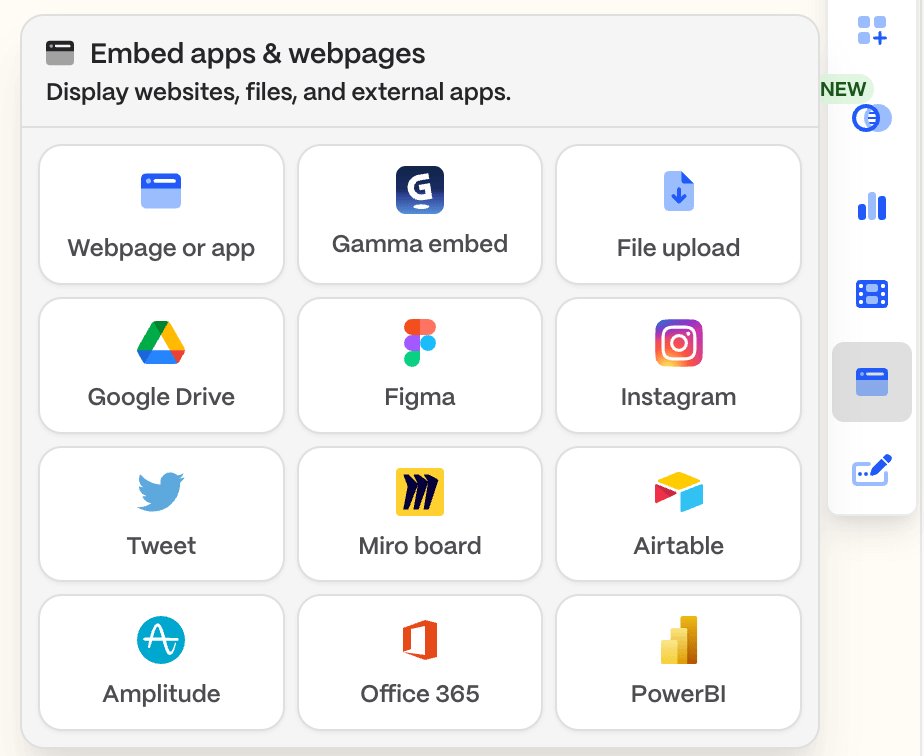

Opening up Gamma, on the other hand, is a different sort of energy. Your first encounter with the product, at the start of your hero’s journey, isn’t a blank slide that must be built to survive (and then another, and another.) Instead, it’s a prompt box: “Describe what you’d like to make.”

From your first interaction with the presentation, your relationship is different. You have to explain yourself: “Here’s what’s going on.” You can take all the time you need, but you need to actually think through the situation and make sure you’ve provided all of the context that you need for a good result. And that sets you up to do a different kind of thinking, and a different kind of work.

Slides: the original slop

Critics of AI tools, whatever they might be hating on, usually converge on a common line of attack: “These tools ruin our thought process, because they train us to think of work as, “Tab tab tab, please fix, next next next.” The accusation is that AI tools rob you of your capacity for thinking. When the tool is too much of a crutch, the output becomes slop.

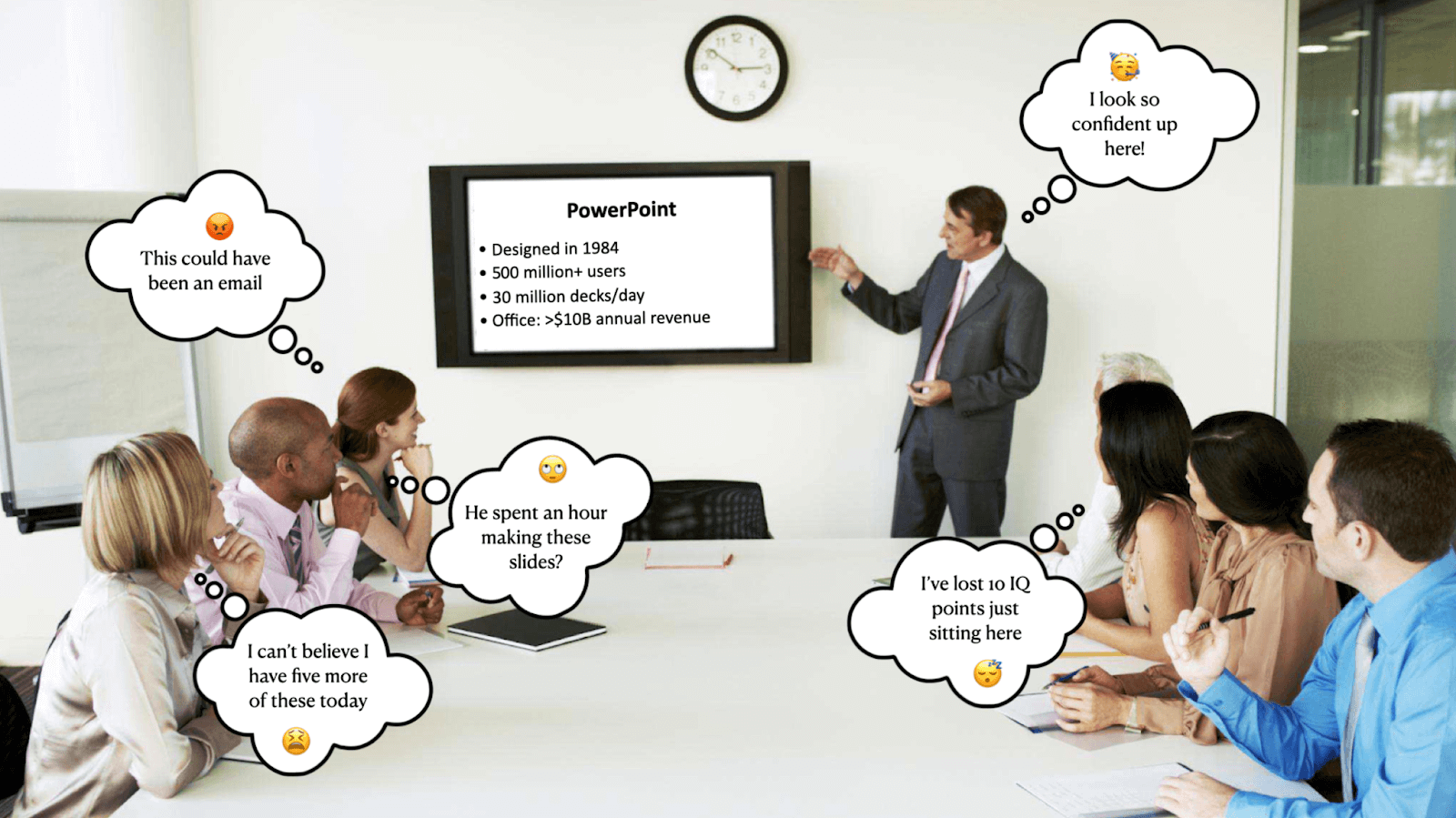

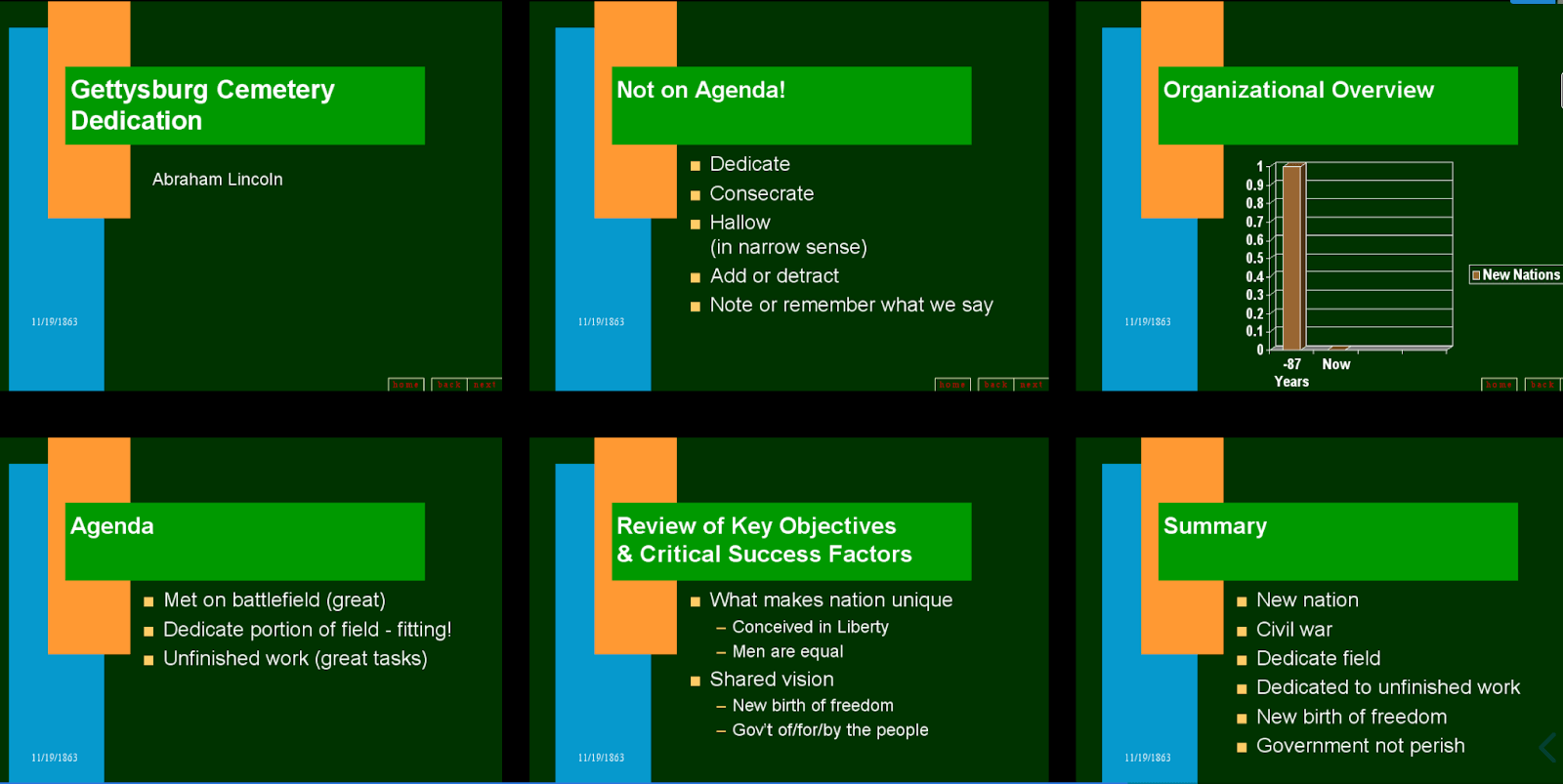

The irony here is that this is already something we’ve said about PowerPoint for decades. Slides are the original slop! Compared to a written Word document, which is well suited for communicating a complex idea, it is tremendously difficult to build a slide deck for such a purpose without getting lost in the sauce. It is very easy, on the other hand, to create something like this:

Rich parallel narratives in PowerPoint aren’t impossible, but they don’t flow naturally from the interface. The deck format – “One damn slide after another”, in Tufte’s famous description, is a medium defined by its primary constraints:

- Bullet point lists

- Jump cuts between slides

- See how these bullet points jolt you out of the nuanced picture and into stop-motion?

Compared to a paragraph or a page of writing, the slide deck format steers you into a strategy to slice your argument into a linear sequence of story components. These days the “Jump cut” technique is mostly associated with Youtubers and Tiktokers, who cut videos into more and more jarring cut-cut-cut sequences; but PowerPoint is really the medium that mastered this frontal assault method years ago. Here’s Tufte again: “With information quickly appearing and disappearing, the slide transition is an event that attracts attention to the presentation’s compositional methods. Slides serve up small chunks of promptly vanishing information in a restless one-way sequence. It is not a contemplative analytical method; it is like television, or a movie with over-frequent random jump cuts.”

By this point you’d be within bounds to interject, “Well, don’t Gamma presentations suffer from the same problem?” The constraints of slide-by-slide, line-by-line, seem to be common to the two formats when you’re making a presentation. What’s different is how those fractal units of information come into being; which in Gamma’s case, is the tricky but rewarding task of prompt engineering it to get into starting shape.

Great slide decks obviously are possible; when you see one, you know. The problem is that we so rarely produce them. Because the interface of sitting down with a bunch of blank slides is so obviously the wrong way to start building a presentation; or at least, it’s obvious as soon as you try using Gamma and get used to a prompt box as your new interface.

“What is going on here?”

I cannot understate how important it is to start with the prompt box, as the framing device that shapes your approach to the problem at hand. In contrast to the “start by editing empty slides” format, the prompt box is a native interface for opening up your lateral thinking.

At this critical stage of the product, you’re just trying to explain yourself. You are not concerned with the problem of “any given slide has to stand up to scrutiny as to whether you have the authority to present it.” You don’t need the salve of jump cuts and fractally compartmentalized bullet points to deal with the intractable problem of mandate constraints, because at this moment it’s just you and the AI, and you just need it to appreciate what’s going on – non-judgementally, no-stress. It’s not your boss. It’s a robot that just wants to understand.

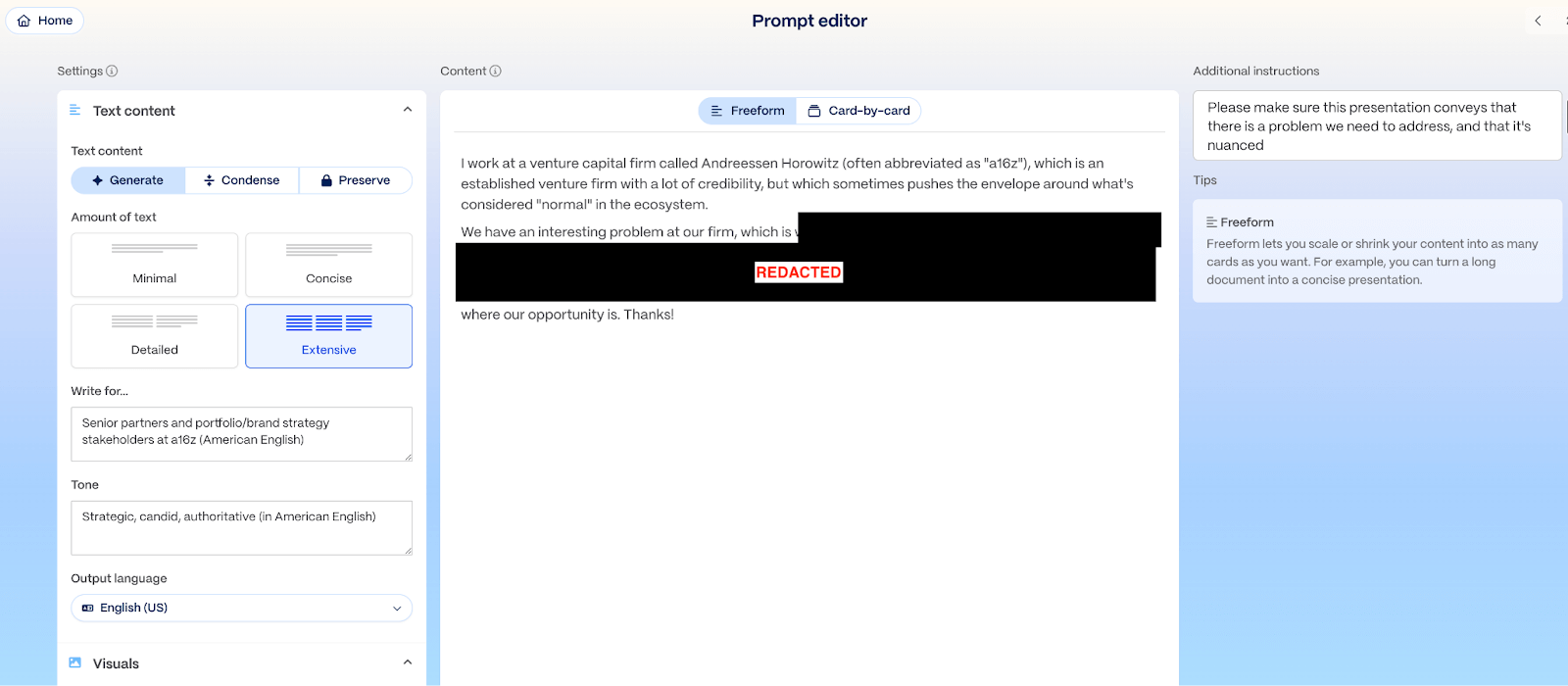

Prior to learning more about Gamma as a part of their fundraising process, I started playing around with the product for the first time – I’d never actually used it before. And man, let me tell you, that initial prompt box (which expands into a more powerful dashboard once you click through) is a powerful format for getting you to actually think through the situation. I tried putting it to work on a problem we’re thinking through on the New Media team right now, and I was absolutely blown away by how effortlessly the product guided me into actually thinking critically about the presentation, and how effortlessly it set our conversation up for success. It made us think better.

I regrettably cannot share any more of this presentation with you, but I was astounded by the results.

Of course, you have to assemble and tweak your slides later on; that’s still (for now) a reality of making a presentation. But, proportionally, you spend much less time on the jump-cut slide interface, and quite a bit more of your time pondering the actual problem. Moreover, for every given slide that needs to show something, you have the same potential: “What do I want this to do?” as your starting prompt to build a slide out of company content and data.

As Gamma builds out the product and gets deeply integrated with company data sources, you can easily imagine the prompt box within a slide as the very best way for an executive or manager to interrogate their company data and explain it. You have agency within this product to actually go represent how the organization works, where an opportunity is emerging, or how a problem actually manifests. You have the same agency over the problem as a software engineer has in front of VSCode: “What is going on here? What do you want to do about it?”

When it comes time for the presentation itself, the other amazing thing that’s different about Gamma is that the presentation itself is intended to be consumed non-linearly. You can swap it into text, you can effortlessly click into embedded topics if you want to explore them, and you can take many different paths through the story depending on where the conversation takes you. You’re less stuck in the tyranny of linear sequence, since the software is not really a set of slides; it’s a composition of ideas that happen to be rendered that way, but also can render in other ways to fit the situation.

This is part of why Gamma has extended so naturally into other formats beyond the slide deck, like creating web pages. It reminds me of the feeling you had using Dreamweaver or other early website builders back in the day – like you suddenly have all this agency to tell a story in whatever creative way you want.

The mandate is the message

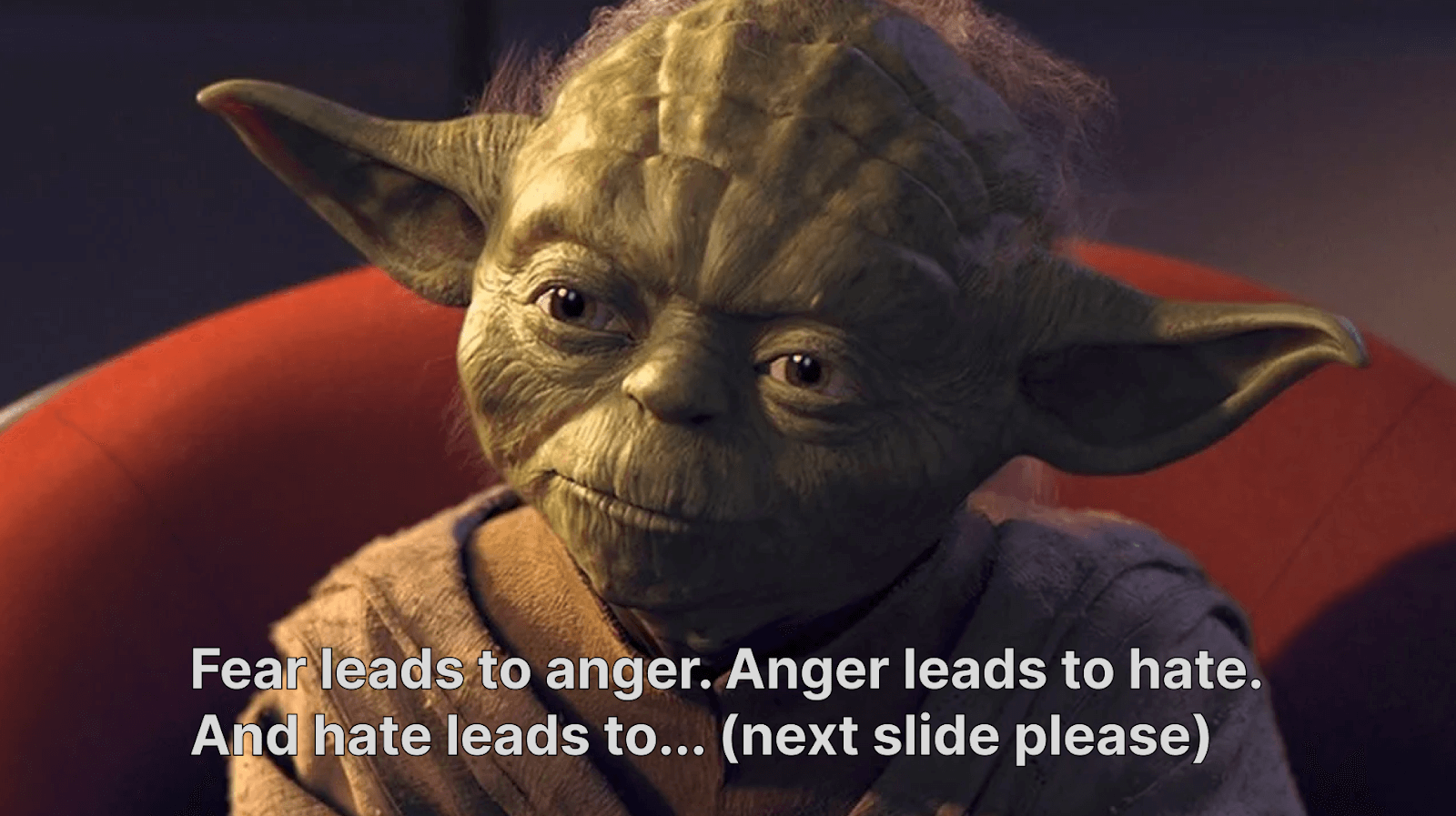

Gamma’s prompting interface does another important thing beyond improving presentation quality. It also helps us unlearn something important, which is the fear that comes bundled with the slide deck medium: “Don’t you dare extend an argument outside of the boundary of the slide: you will be misunderstood, and it will be held against you.”

Maybe more than any other reason, I think this is why people hate PowerPoint so much: because hate, at the end of the day, comes from some sort of fear. This is where Gamma’s impact on work gets more profound, into less measurable but more emotionally significant territory.

The unstated rule of PowerPoint is that the narrative sequence of both the whole deck and of any bullet point sequence within the deck must silently conform to the company’s org chart. That’s because the central challenge that every slide-builder must confront is that every bullet point, and every slide, must defend its existence in isolation. You only see one slide at a time, and since any given slide could get stuck on the screen for forty minutes, they must be built for the presenter to survive that experience. No slide can afford to appear illegitimate to the presenter’s mandate; therefore no chunk of information can, either.

Most of the time, PowerPoint is not exactly doing harm; it’s just going to steer you somewhere uninspiring. But occasionally the slide format can actually derail things in a bad way. When every bullet point and slide must defend their existence alone, they are more likely to present fully untested or inaccurate assumptions as fact. Their validity derives from their eligibility, not from their factual or contextual legitimacy.

Compared to writing a paragraph or a page, where the medium naturally wants to express, “What is going on here?” a slide deck wants to tell something different: “What is the mandate of the presenter?” which is a fully different thing. Tufte wrote that slides “[ram] through unstated assumptions, not because the presenter does not want to address them, but because they cannot address them; they are powerless to do so.” The purpose of the bullet points is for the presenter to survive scrutiny, not for the message to do so.

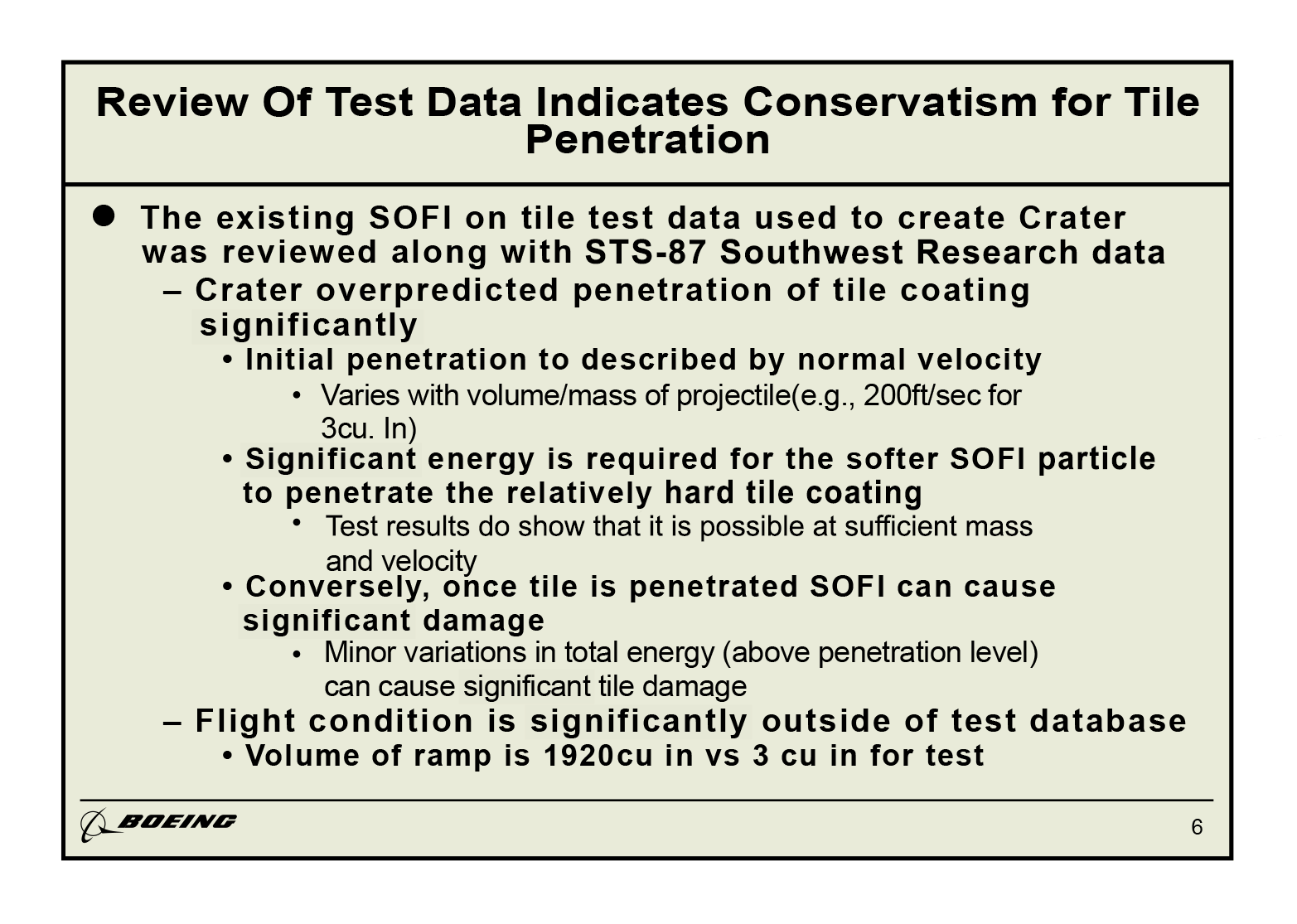

Tufte’s famous essay culminates in his half-trolling half-serious accusation that PowerPoint software is to blame for the Challenger Space Shuttle explosion. (Specifically, for NASA’s calculated dismissal of reentry risk, despite observed problems at liftoff. Tufte’s accusation isn’t out of left field; NASA took the notion seriously in its postmortem.) It’s a familiar claim to anyone who’s ever worked in a big company: the engineers knew there was a problem, they tried their best to communicate the problem, but their mandate and medium constrained them to present that problem in a particular way that buried their call to urgency.

The written message ought to have been pretty clear:

“The space shuttle suffered damage in liftoff, and our prior test data (which suggest that such damage is no big deal) is irrelevant because the scope of the present damage is hundreds of times larger than what we had tested.”

In contrast, the PowerPoint version maps to the org structure: the fact that reassuring test data exists in the first place occupies a more senior bullet point than its sub-propreties, including “it is sometimes not applicable, including right now”:

We’ve tested for this before, and it was fine

- When we simulated this sort of damage, it wasn’t a big deal

- However, the on-the-ground conditions are far outside the test conditions

This is a good illustration of learned helplessness. Whoever assembled this slide knew exactly what the stakes were and what the data (didn’t) show; but reached a slide title all the same: “Review of Test Data Indicates Conservatism for Tile Penetration”. The mandate was the message.

There’s a famous quip called the Peter Principle, which you may know. It goes, “People are promoted within organizations until they reach a level where they’re incompetent at their job; at which point they stay there.” You can imagine a corollary for our modern workplace: “The first job level at which you struggle in the role is the level where you’re most competent at PowerPoint.”

I honestly think this is true, in some sense. Anyone who’s well into a professional career has experienced, at some point, the scary feeling that they have lost control over their situation. This often comes after a promotion, maybe into a managerial or a staff role, where you’re in some small crisis and you must construct a slide deck for a meeting to try and rescue things. This is a tough situation, and I feel for each one of you that’s recalling some such experience from your past life. In that moment, the job-to-be-done of PowerPoint is therapy. It tells you, “we’re going to make it through this, together”: not by solving the situation, but by surviving it, with the divide-and-conquer method into slides and bullet points.

If your goal is to survive, PowerPoint is your ally. But if your goal is to actually acquire some agency over the situation, and make a difference to your business, you should try something new.

Agency for anyone

One of the funny subplots of PowerPoint history that many people don’t know is that the software program itself – from whom every copy of PowerPoint has descended since – was written by Whitfield Diffie, the cryptography legend of Diffie-Hellman key exchange, who prototyped it at Bell Northern Research. (His involvement more or less ends there, though.) The real “founder” of PowerPoint that we recognize in hindsight is Bob Gaskins, who really created the product and grew it through its acquisition to Microsoft.

Gaskins’ original goal for PowerPoint, ironically, was to help presenters gain independence from the organization: by freeing them from dependencies on graphic designers & presentation professionals. From Ian Parker’s New Yorker piece: One phrase [of Gaskins]—the only one in italics—read, “Allows the content-originator to control the presentation.” For Gaskins, that had always been the point: to get rid of the intermediaries—graphic designers—and never mind the consequences. Whenever colleagues sought to restrict the design possibilities of the program (to make a design disaster less likely), Gaskins would overrule them, quoting Thoreau: “I came into this world, not chiefly to make this a good place to live in, but to live in it, be it good or bad.”

In a funny way, Gamma has picked up that motive and run with it, towards a frontier that I’d like to think that Gaskins would’ve appreciated. The big goal is to give you agency. Because agency is upstream of everything you actually want out of a slide presentation, and from managers and decision owners.

Gamma, at its best, feels like working with a coach. They’re here to understand, to give you a mirror for your thoughts, to help bring out the disparate threads of the problem. And they’re here to help you perform at what your job actually is – “make the business better.” It’s part of an important category of AI use cases where, in an important way, the AI is much better than a human. In this case, it’s because the minute you talk to a human about a business problem, you’re exposed to Conway’s law, and to the political reality of the organization, before you can properly sort out the different strands of the problem and synthesize an interesting path forward. But when your counterpart is a neutral, curious tool that just wants to understand what’s going on, the job itself comes back into relief, long enough for you to do something about it.

PowerPoint could, when used at its very best, illuminate unobvious truth & effect real change inside organizations. Its users have achieved greatness, occasionally. But tools matter, and default interfaces matter, because anyone who is curious and capable in their job can achieve greatness if they’re given the opportunity. Every presentation should be that opportunity, for anyone. And with Gamma, I think more of them will.

Gamma is hiring! You can check out open roles here.