In the 2000s, hundreds of millions of people devoured web games like Bejeweled and FarmVille, powered by Adobe Flash. In contrast to siloed console or PC games, these browser-based Flash games were incredibly accessible: they could be played instantly by clicking a web link and shared easily via email or messages. Yet as smartphones and app stores have grown ubiquitous over the last decade, native apps — those installed directly on hardware — have largely won out due to performance and security advantages. Adobe Flash itself was officially deprecated months ago, marking the end of an era, and of a technology that many game developers credit with jumpstarting the modern games industry.

Yet while Flash may be dead, its legacy lives on. Thanks to improved technology and new platforms, we’re on the cusp of a resurgence in instant games, which do away with downloads and long-winded onboarding flows. A new class of instant games today melds the click-to-play ease of early Flash games with the quality and performance of app-native games. Platforms like Snapchat, Facebook, and WeChat are already embracing instant games in different forms.

This frictionless, inherently social mode of play has the potential to vastly expand and democratize access to games, unfettered by the constraints of hardware. And in the near future, a decentralized network of these experiences could disrupt — and even surpass — the dominance of the App Store itself, upending how we develop, discover, and distribute games.

But first, wherefore Flash?

Since its inception two decades ago, Flash games had two key benefits: accessibility and ease of creation. Flash games loaded in seconds, without downloads or installation. And since Flash was supported by the majority of web browsers at the time, the games were inherently cross-platform. Without barriers to entry, successful Flash games spread like wildfire: The Pong-inspired Flash game Insane Orb, for example, was played over 46 million times on a single website. Flash’s web distribution also allowed creators to bypass the publishers that controlled retail distribution for PC and console games at the time. Anyone could host Flash games, which led to the creation of thousands of web portals like Newgrounds and Kongregate that curate and promote the best titles.

Most importantly, Flash games were relatively easy to build due to an intuitive scripting language and workflow that incorporated art and animation. Flash games could be built in just months, compared to years for console and PC games. This ease of creation not only encouraged experimentation, it opened doors for aspiring creators. Almost anyone could launch a Flash game — and if it wasn’t successful, a new one could be made quickly. As a result, the Flash decade from 2000 to 2010 has often been described as one of the most creative periods in games history.

In fact, many of today’s most recognizable game studios, including Supercell and Zynga, started out building Flash games. But as in-app mobile gaming took off, Flash games waned. In an open letter to Adobe in 2010, Steve Jobs famously condemned Flash, arguing that it was unsecure, closed-off, incompatible with mobile, and a drain on battery life, among other critiques. Seven years later, Adobe announced that Flash was nearing end of life, with the company officially deprecating the standard earlier this year.

The next avatar of Flash: instant games

Yet over the past few years, new technologies and platforms have led to the rise of the next generation of instant games. Like the original Flash games, next-gen instant games are frictionless, accessible through links, and relatively easy to create. But unlike their forebears, modern instant games can run at near app-native quality with console-level graphics.

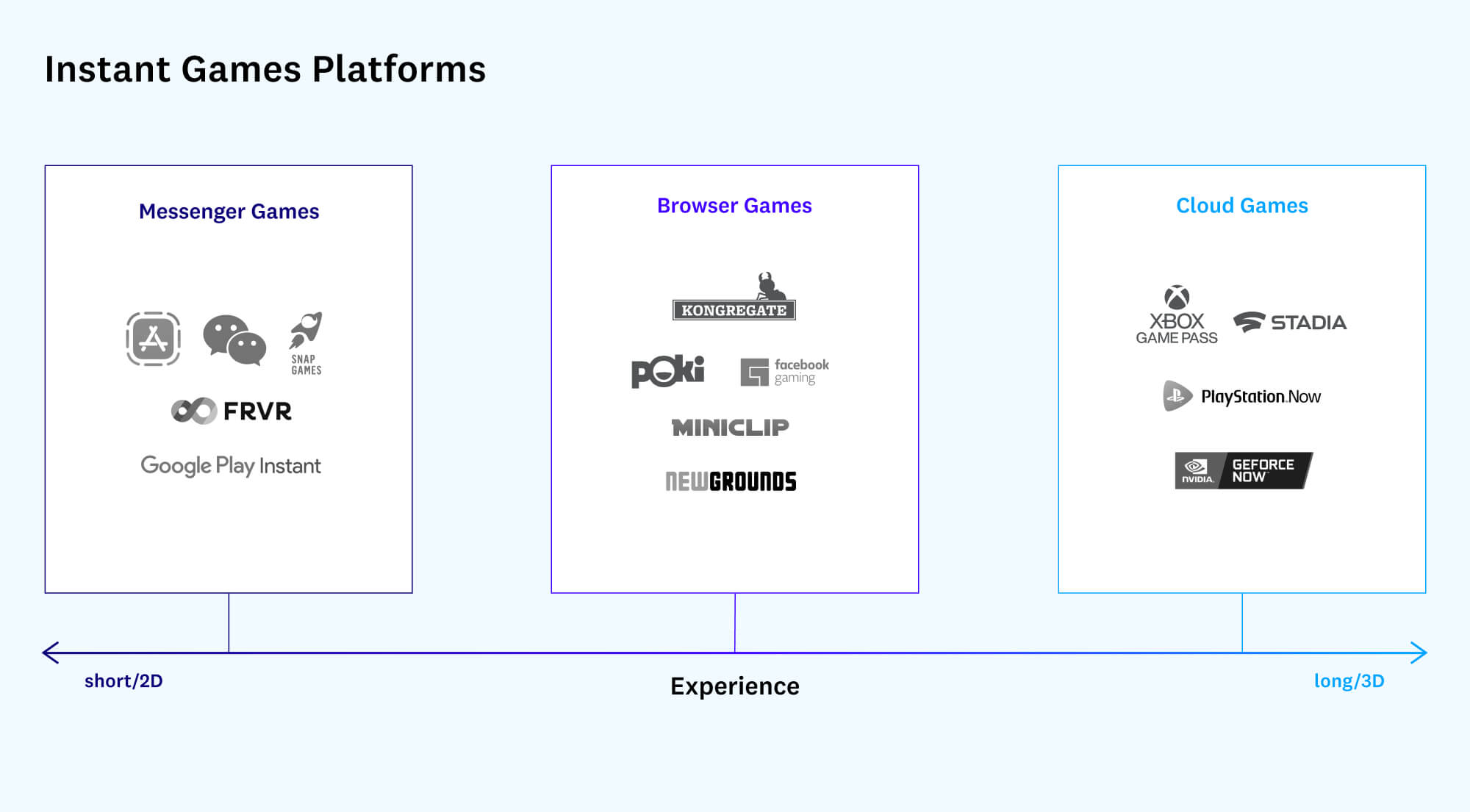

So, why now? For developers, there are more ways to create instant games than ever before. Apple and Google have been pushing binary streaming via App Clips and Google Play Instant, which enables users to play game segments on their smartphones without app installation. Messenger-based platforms like WeChat have created an entire ecosystem of games as mini programs or “apps-within-apps.” Browser games portals like Newgrounds have been on the rise again with over 29 million visits in the past six months. Microsoft is investing heavily in cloud streaming AAA PC/console games through xCloud, and Facebook is streaming mobile games with Cloud Games.

These platforms all focus on increasing accessibility via instant play and reducing barriers to entry for users.

Web apps have also made tremendous progress in the past decade. While early HTML5 apps — the web standard that partly contributed to the deprecation of Flash — suffered from latency and responsiveness issues, modern web apps have made significant strides in performance optimization, from asynchronous JavaScript and lazy loading to larger CDN networks. Modern web apps written in WebAssembly or JavaScript frameworks can run complex programs at near app-native quality levels and at global scale. Netflix and Twitter are both constructed as web apps, for instance.

Graphics rendering on the web has also improved significantly. Open-source APIs such as WebGL and WebGPU provide web apps with access to GPU acceleration, enabling full 3D games to be rendered in-browser. As tablets and laptops start packing console-quality integrated graphics chips, we are not too far off from a future where browsers reach graphics parity with the latest generation of consoles. Web-based 3D engines are also emerging, such as Babylon.JS and Playcanvas, which allow developers to construct 3D assets and worlds more easily. Using Babylon, Mojang recently launched Minecraft as a web game where players use a custom URL to invite friends to build voxel worlds together in-browser.

The instant social network

Beyond the underlying tech, however, is what these games enable today: social. Next-gen instant games are poised to capitalize on the social networks, video discovery channels, and new social mechanics that have emerged over the past decade.

In the Flash era, social activity centered around networks like MySpace and Facebook; today, instant games can spread via links on Discord, Facebook Messenger, Reddit, Snapchat, TikTok, WeChat, and Whatsapp, to name a few. Because of this, successful instant games today can grow at a staggering rate. Tiao yi Tiao, a viral “jumping” game on WeChat, hooked 100 million daily users in just two weeks, primarily through players messaging their friends.

Modern instant games can also go viral on video platforms like Twitch and YouTube, both of which rose to prominence after the Flash era and now drive game discovery. Instant games that are easy to understand and playable in-browser are especially ripe for streaming due to the ability to drop in at any time and get the gist.

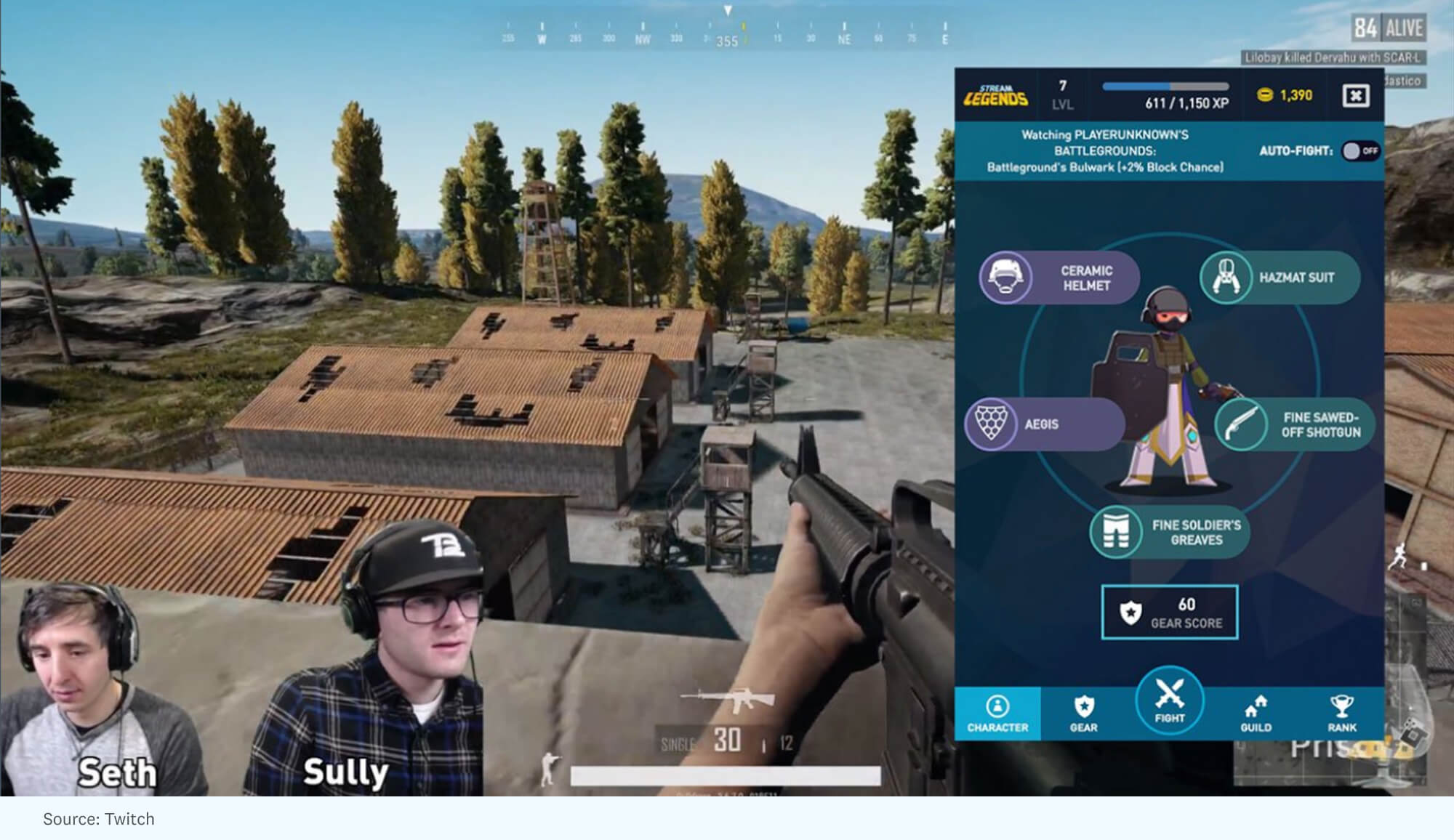

An entire ecosystem has emerged around Twitch extensions, which are mini web apps that run on top of a livestream and add new functionality such as leaderboards, overlays, and mini-games. Proletariat’s StreamLegends extension, for example, is a mini-RPG installed on over 50,000 channels; viewers help build a streamer’s town by battling monsters and collecting loot, all played in-browser and on top of a livestream.

When you combine social with video platforms, it becomes evident that the market could be larger than ever before. The hit social deception game Among Us grew from hundreds of users to 500 million monthly users on mobile and PC in a year, fueled largely by social media memes and Twitch livestreaming. Not only did a few popular streamers broadcast Among Us to their followers, but multiple livestreamers would play the game together, multiplying their social reach. How much larger could Among Us have been if it were an instant game? What if anyone could drop in and start playing instantly without having to download an app?

The next billion-player game could very well be an instant game that combines similar multiplayer social mechanics with frictionless, drop-in gameplay. This game could spread virally on all social networks and video platforms. And if built as a free-to-play, live-service game that is continually updated post-launch, players would be able to spend thousands of hours immersed in the game across any internet-connected device.

Of course, there are still hurdles to overcome on the way to achieving this vision. Pointing to low retention numbers, many industry veterans today dismiss instant games as a fad. What’s often overlooked, however, is that the majority of instant games today are casual, single-player experiences — very few have long-term progression systems or social features built in. A high-quality instant game built from the ground up to be inherently multiplayer — and run by a dedicated team with free-to-play games expertise — would likely result in a very different player retention profile.

Distribution, distribution, distribution

We’re already seeing signs of this future of instant play. Snap recently announced that over 200 million users have played instant games on its platform, 30 million of whom are active every month. Voodoo’s Aquapark.io, a waterslide game, launched on Snap last fall and has already reached over 45 million players. Playco‘s EverWing, a vertical scrolling shooter game, has over 400 million players on Facebook. End Game’s Fortnite-inspired battle royale game ZombsRoyale.io — where 100 players compete to be the last person standing — has reached over 80 million players across web and mobile, according to its makers.

But while those numbers are considerable, these games all reached sizable audiences mainly on a single social network or hardware platform. As instant games grow in scope and incorporate deeper multiplayer experiences, it’s inevitable that we will see an instant game go viral across all platforms, breaking out of today’s walled gardens.

And as these cross-platform instant games become more popular, distribution will likely move toward a more decentralized model. Instead of going to a central app store, we would discover and play instant games based on links shared by our friends and family. So what happens to app stores in this new world? They would become less gatekeeper and more curator. In this model, game developers would be able to engage with and distribute to their audiences directly, picking and choosing the right platforms for a particular genre or target audience. As game developers directly monetize their audiences via commerce, subscriptions, tips, and other approaches, we will continue to see new business models for games emerge, beyond ads and in-app purchases.

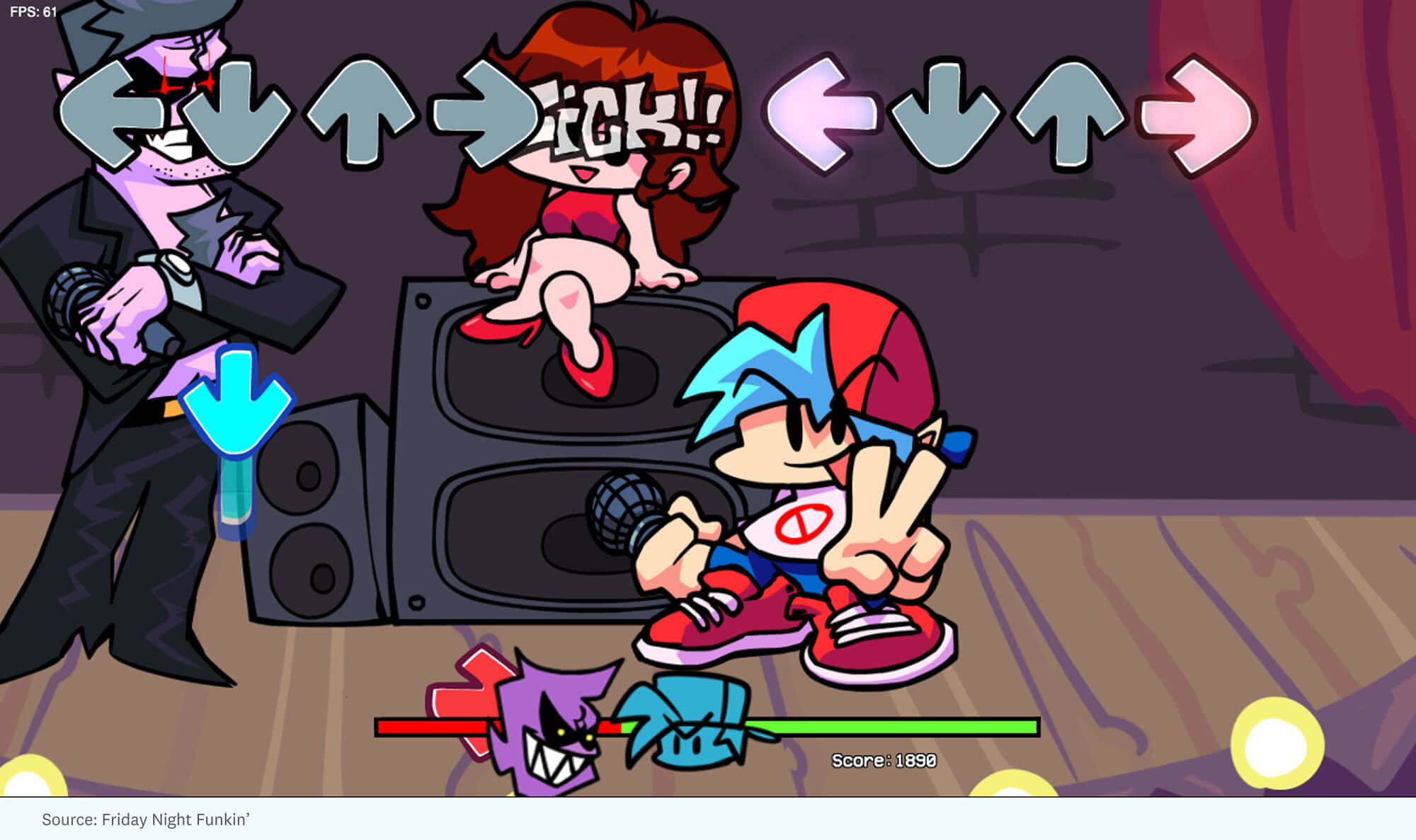

If 100 hundred true fans becomes all it takes to set up an instant games studio, we will also see the rise of a new class of game creator — one that straddles the line between game developer and influencer. And with open-source libraries, cloud computing, game engines, and no-code tools, it will be easier and faster than ever for all kinds of creators to build games. A team of just four friends made Friday Night Funkin, a Dance Dance Revolution–inspired instant rhythm game that has garnered over 30 million plays and more than $2 million in donations.

* * *

If cloud-native games seek to revolutionize the games industry by building new types of high-end games that we’ve never seen before, instant games represent low-end disruption, from the bottom up. The potential market is all the gamers who are currently over-served by consoles and gaming PCs, as well as those who don’t self-identify as “gamers,” but would play if the right game and friends were just a click away.

Long-term, it’s likely that these two motions — instant games from the bottom up and cloud-native games from the top down — will converge. One thing is for sure, though: Those who dismiss instant games at first glance risk missing out on the new 4 billion-person game board that’s being formed, as all internet users become gamers.