Fifteen years ago, if you asked “what are smart people doing on weekends?” a really good answer would’ve been “making YouTube videos.”

YouTube celebrated their twenty year anniversary earlier this year, and while we all enjoy a good reminiscence of the early videos that made us laugh, we don’t always appreciate how countercultural it was to actually be a YouTuber in those early days. Even after the YouTube Partner Program launched in 2007, the idea that you could earn a living from a channel seemed far-fetched for a while. The world already had so much video content, from the major studios down through the long tail of the 110th channel in your cable bundle: how could there possibly be any commercial demand for even more?

We now know, in hindsight, that the world was actually short video 15 years ago. And we know that because of what’s happened on YouTube since. When anyone with a camera and an editing suite can find their audience, we discover all kinds of channels and businesses – from Hot Ones to Mr Beast to Dwarkesh – that obviously deserve prominent placement in our content universe. The supposed “long tail” was so much bigger than anyone could’ve known.

Maybe this is the right historical guide for thinking about LLMs, web apps, and the future of the internet. YouTube changed content forever by collapsing “creatively making content” and “running a microbusiness” into a straightforward sequence of steps. You still needed to be creative and driven, but the rest got a lot simpler. So why shouldn’t we see the same thing happen with software?

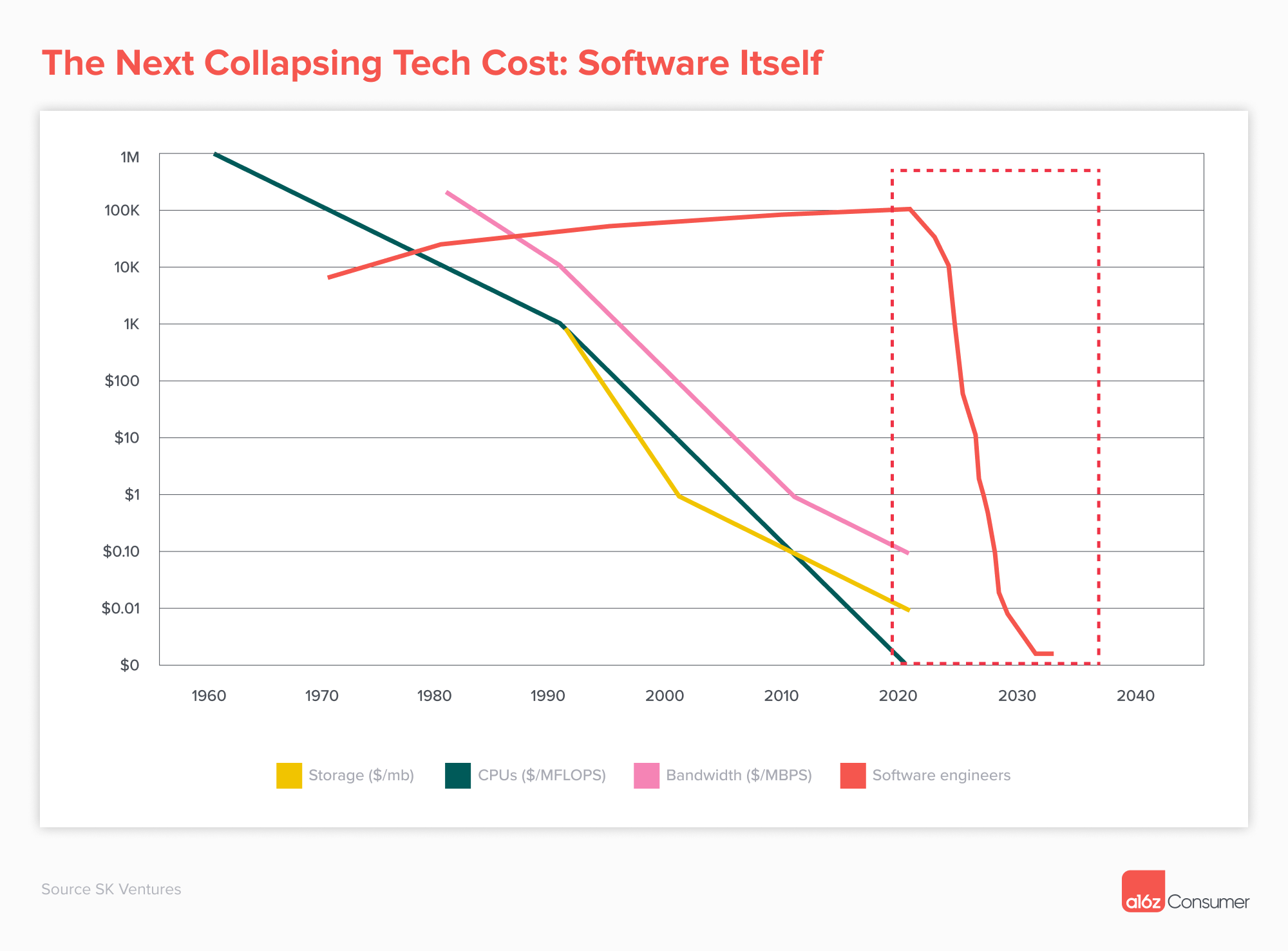

The web has always been great at facilitating permissionless creation by anyone. But it wasn’t until LLMs that the definition of “anyone” changed from “developers” to “literally anyone with an idea and access to a coding agent.” Five years from now, we might look back and realize that the world was short software, because the only people equipped to build it were engineers. In other words, this is the YouTube moment for the rest of the internet:

- “The world is short software” is a thesis that’s equivalent to “the world is short content” in 2006. In 2006, you would’ve pointed to 100 cable channels and said “this is enough.” The same is true for the state of software and websites today.

- LLMs finally make it possible to build niche software and apps that previously would not have made it to market. You wouldn’t hire a bunch of engineers to build a product for 100 people, but you can build (and monetize!) smaller-TAM products using app-gen and coding tools.

- Long tail web apps will be built by a particular kind of “professional”, and Youtubers are the best template we have for what that kind of professional looks like

Content is now an application; apps are now content

Paul Bakaus has pointed out that when people talk about the internet, they’re actually talking about three distinct things: the content layer of the web, which consists of blogs, sites like YouTube, Substack, and traditional publishers, the commerce layer of the web, which consists of marketplaces like Amazon and Shopify stores, and the app layer of the web, which for the majority of the internet’s history consisted of “serious” cloud-based software, like enterprise platforms and social networks.

LLMs influence all of these layers in different ways. The commerce layer is the subject of another post, but we’re definitely seeing LLMs play a major role in product recommendation and purchasing; not only in novel AI discovery mechanisms like search, but more importantly in the recommendation engines themselves. But commerce aside, there’s a big reorientation afoot around how we think about “content” on the internet, and how you’re rewarded for it.

Content has always been the “traditional long tail” of participating on the internet, back 30 years to the first web browsers and beyond. And every decade, there’s a major storyline around that long tail of content getting captured by some centralizing force: AOL initially, or Facebook later on.

This time around, the big storyline is that LLMs crawling websites are a new and even worse form of content capture – because they effectively become the application by which you consume information that historically would’ve been traffic to the content creator. Publishers despair over a phenomenon called “Google Zero” (the day organic search traffic asymptotically approaches nothing), while an interesting set of new forces push back, like Cloudflare’s foray into pay-per-crawl and into new micropayments standards like x402.

Meanwhile, something fascinating is happening on the other end of the internet: apps are becoming the new content.

In the long run, the internet gets more participatory

There have been entire categories of software that were never built, simply because of insufficient ROI, too much cost, or because the preferences of ~20 million developers dictate the software we all use. But we’re going to find out what they are, very soon.

It’s now easy to prototype, build, and ship entirely novel applications, using new app-generation tools like Replit, v0, Loveable, Figma Make, Bolt, and Base44. Previously, this would have required engineering know-how and maybe even an entire team of developers. Now, you just need $200/month (or less!) and a good idea.

There’s a well-known joke that the majority of Gen Z have aspirations of being a professional YouTuber or TikToker when they grow up. People love to argue and finger-wag about whether this is a realistic goal, and ignore a more basic observation: kids yearn for entrepreneurship and the American dream on the online frontier. And the main outlet for that aspiration thus far has been YouTube and TikTok.

LLMs enable an entirely new kind of creative persona on the internet. If you’re a passionate person who wants to build and monetize your app ideas, now you can. In a previous era of the internet, you would have had all kinds of upfront costs that would have been prohibitive to get an idea off the ground, and you would have needed a constantly-increasing number of customers to justify your existence. With LLMs, it’s easy to ship a product and get paying users quickly.

Here’s a concrete example: my wife has recently gotten into manifestation. She is scarily good at it (so much so that I am now extra careful about getting on her bad side). She’s now building an online app for her friends to learn the practice of manifestation too. A few years ago, she might have advertised this service on Facebook, and struggled to make the content engaging and dynamic for her audience. Now she can build an app and own her relationship with her customers directly.

And I know for a fact that it’s not just happening in my household: I’ve seen everything from a lofi Brazilian air traffic control streaming site to a platform for jamming with an AI band, built with Replit. As an indication of how powerful this is: earlier this year, Replit hit 150M in ARR, and is seeing demand take off for their coding agent offerings.

We also should expect to see this phenomenon expand beyond the web. Companies like Wabi are making it easy to build entirely new personal mobile apps around things like weight-lifting, clip-art generation, fasting, and reminders to touch grass.

Making apps: a new kind of show business

A few years ago, Nadia Asparouhova wrote a fantastic book with Stripe Press called “Working in Public”. The book told an interesting story about how the work of open source software development was changing in the Github era: how the maintainers of popular projects have to spend a lot of their time managing fans who want to participate and contribute. Making things in public is starting to become a kind of “show business”. It’s not enough to make something good – you have to think almost like a streamer.

Now, with vibe coded apps and the long tail of software, we may see something similar play out at much bigger scale. It isn’t quite the same challenge, but the skill set is probably the same: the people who succeed are going to be a certain kind of professional. A totally different kind than the “professional” software developers who came before, who have different instincts around the medium and how to build things that resonate.

It’s worth remembering, with some humility, that virtually no incumbents from the traditional TV world became big YouTube stars. For a long time, the major TV shows (like late-night comedy shows) treated Youtube as a dumping ground for “Extras” like bonus footage or outtakes. It’s entirely possible that traditional software builders and investors end up misunderstanding vibe coded apps in the exact same way – not dismissing them entirely, but missing their purpose.

Just like we saw with YouTube, the most successful new apps will likely be driven by individuals and personalities: these are people who have existing distribution, who’ve already created natural schelling points for their communities, and who build “unboxing videos, but software”. But platforms like Wabi also point toward a different possible outcome for this too. We may see hyper-personalized applications on the web, for much smaller audiences. This is tremendously liberating: software no longer needs to be practical. It doesn’t need billions of dollars in revenue to justify its existence. It just needs to have a good idea behind it, and a couple of people who understand its value, and appreciate the professional instincts – professional ala Youtuber – that it takes to succeed.