Go to Europe these days – to Berlin, London, Helsinki – drop in on any of the regional tech confabs and you will quickly see that the European startup scene is in the most bustling, vibrant shape it’s ever been. The potential is everywhere, and the energy is undeniable. Then you return Stateside, in my case to Palo Alto, and Europe isn’t just irrelevant among the tech industry power-set. It has virtually ceased to exist.

That is a mistake. Blame for the ruptured relationship lies on both sides of the Atlantic, but it is Europeans that have the power, and should have the motivation, to mend things.

I’m proud to be Estonian and European, but recently realized that very soon I will have been living in California for 10 percent of my life. I had a front-row seat to the first Internet boom as an exchange student at the super-wired Monta Vista High School in Apple’s backyard. I returned to the U.S. with some frequency initially as an executive with Skype, and later to pursue a business degree at Stanford. My latest perch in Silicon Valley today is as an entrepreneur-in-residence with venture capital firm Andreessen Horowitz.

Let me give you a small taste of the way Europe was woven into the discussion at Stanford’s Graduate School of Business. Over the course of four quarters I heard one professor make one joke about short-term macroeconomic troubles in Greece. We also had a visit from a well-dressed and charming British banker in our private equity class. That’s it. No European startups, no cases of European success stories or failures. A joke and a banker.

A few isolated examples of systematic bridge building, like the fantastic five-years-running European Entrepreneurship seminar at Stanford’s Engineering school can fulfill targeted curiosity, but Europe is not visible as a theme in other classes across the curriculum.

Important Places

I’m not blaming Stanford. In talking to many people about my growing realization that the place of my birth simply didn’t matter to most people in the Valley, I began to understand that there is a mental hierarchy of “important places” for people building, investing in and studying tech companies in Silicon Valley. They exist in the following order:

1. Silicon Valley. Practically considered, the opportunity cost of venturing out of the bustling 30-mile radius of Sand Hill Road, whether you are an entrepreneur, investor or academic, is usually just too high.

2. The U.S. East Coast. Yes, stuff is happening in Boston and New York, but not so much that a once-a-month trip can’t cover most of it.

3. China. Massive tech companies do rise in China and go public in the United States, and Chinese investors have gobs of cash to invest in the Valley. There is a constant back and forth between both Pacific coasts. But it’s not just geography, and the historic manufacturing relationship that is stimulating this cozy dynamic. The Valley is looking more and more towards China for the next tech trends and expansion opportunities.

4. The rest of Asia. India’s diaspora links to the U.S. are strong. Southeast Asia’s growth is hard to miss, and there is interesting mobile stuff happening in Korea and Japan.

5. Latin America/South America. Markets in Mexico and Brazil are increasingly ripe for Silicon Valley tech, but the region is still a distant gleam for most companies.

6. Europe. Here is what I mostly hear about Europe: “I took my wife/husband to Paris last year for our anniversary, and we dropped by Rome. Great food, so much history, Europe is wonderful!” For vacation.

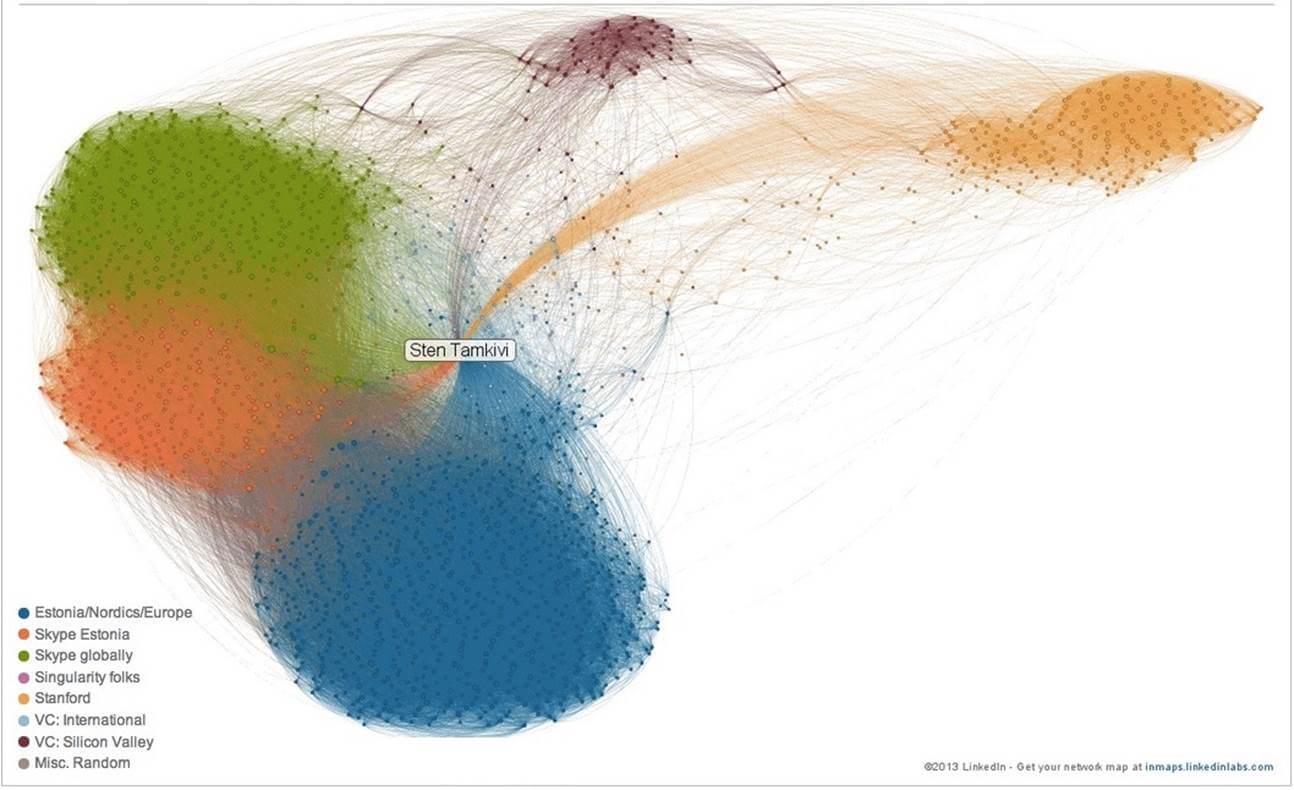

Rather than relying solely on my anecdotal examples of “important places,” I turned to LinkedIn. Mapping my network through the lens of the topic at hand, I can confirm that, while Estonia, the Nordics and Europe in general comprise a tightly knit blue blob, and Skype in Estonia (orange) and internationally (green) is an organism in itself, the Silicon Valley venture capital and serial entrepreneurship circles float as a distant burgundy cloud. And the international graduate student and teacher body of Stanford is even further out on the right.

Those familiar with Granovetter’s theory about the strength of weak ties should feel a wave of joy here. Sure, there are benefits of weak ties, but then again, there are virtues to tight-knit communities talking to each other frequently, sharing the successes and learning from each other’s mistakes.

And that is exactly what is missing between the U.S. and Europe — a real bridge. So how do we build one, and what can both partners in constructing this connection hope to gain?

Let’s start with Europe.

Why the Hell Are You in Silicon Valley? And Don’t Say It’s the Money

Raising money tends to be the No. 1 rationale from founders when asked why they’re in the Valley. It’s also the No. 1 mistake people make. You will be far more successful raising seed and early-stage VC financing close to home, on whichever side of the Atlantic it may be.

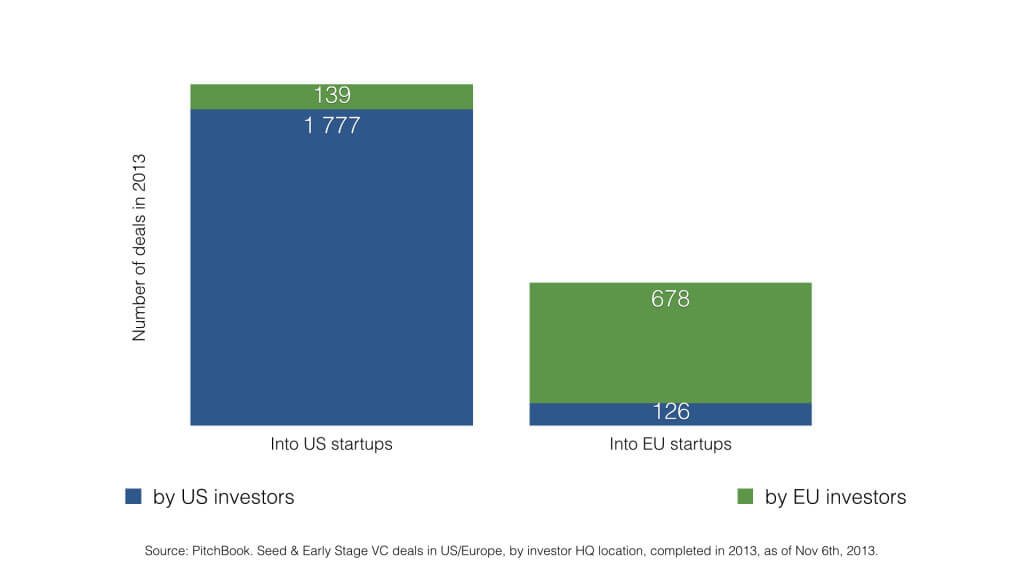

Yes, the internationalization of the venture capital industry is well on its way, and one can draw quite pretty graphs of the increasing money flow across the globe. Bollocks. Here’s why you, European entrepreneur, aren’t going to get that money.

Looking at closed early-stage deals listings in Pitchbook, it is very clear that U.S.-based VCs invest in U.S. companies, and European VCs invest in Europe.

In my experience, this mindset applies to institutional investors in a clearly structured way, but is a notable behavior even for private angels in AngelList. Investors believe that there is much more that they bring to the table than just money – but that ineffable “value” is hard to bring across long distances and multiple time zones. No matter how much the video calling has improved, board seats, hiring networks, corporate development efforts and just quick (unscheduled!) calls work much better in proximity. Raise your money at home.

Part of building a solid bridge with the U.S. is having a solid reason for being here, other than money. Selfies at Infinite Loop Drive and group pictures in front of Facebook and Google headquarters don’t count.

One good reason for touching down at SFO might be that it’s because the companies that matter in your space – the ones you want to compete with, learn from, partner with or steal bored employees from – are in Silicon Valley. Ditto for customers.

That said, you need to honestly evaluate decamping from Europe against your own personal strengths and networks. I am in the thick of things on Sand Hill Road. Yet that relative advantage doesn’t change the fact that I have been building software companies for 16 years in Estonia and worked mostly with teams around Scandinavia and in Prague or London. This is where the best engineers I know are. This is the core of my network. This is my actual unfair home-court advantage.

If anything makes me stay Stateside, it must far outweigh the strongholds I’m leaving behind. That applies to every European (indeed everyone wherever they are from) pondering a move to Silicon Valley.

Why Silicon Valley Should Love Europe Back

So if exchanging money for equity isn’t the way to create tighter bonds between Europe and the Valley, the question becomes: how can we build more non-financial ties between our scenes?

When building high-value ties in any network, the question should never be what you get, but rather what can you give to the other party? What can you help with? What can you teach? What can you spare? This tends to be true with your friends, your community, and your country – and how you ought to think about transatlantic relationships.

If we Europeans can muster the confidence, and the U.S. can tone down its arrogance, Europe actually has a lot to give to Silicon Valley. Here are just a few examples.

Talent. Silicon Valley’s weakest spot today is finding enough good engineers and designers. The European contribution here in the simplest case is talent. The next level of complexity, but more sustainable for both sides, are development outposts across the pond. This could also take the form of M&A targets that Europe could offer – something that Meg Whitman in her eBay CEO days used to call “off-balance-sheet R&D” when buying up another innovative marketplace team in the Netherlands or Sweden.

What about making this a two-way street, and providing interesting-timed job adventures for early-career Valley experts? Why be the 3,481st guy in Facebook, when during a three-year stint in a cool European city you can be No.1 in the entire country in what you do? Yes, moving American hotshots to Europe can be a tough sell, but we did it successfully at Skype, and companies like Soundcloud are doing it again.

Sharing new models. For any European who has spent an extended time here, Silicon Valley can often feel surprisingly backwards. When it comes to online and mobile applications truly embedded in how people go about their daily chores, how they sign and exchange legal documents, how they interact with the government, how they do their consumer banking, how they receive services from their doctors and so forth, many places in Europe are light years ahead of what is widely available in the U.S. We can share those ideas and expertise.

400 million customers. For most successful entrepreneurial ventures, there comes a day when growth needs to be found outside of the home market. And no matter how much the mobile handset makers talk about the next billion people coming online in Africa, and how lucrative the already-online billions of users in Asia are, the most common scenario for the Groupons and Airbnbs and Ubers of the foreseeable future is still to figure out their expansion strategy for the U.K., Germany and France.

Europe is still the rational next market for most U.S. rocket ships who are looking to find customers with above-average incomes and access to credit cards who live on infrastructure you can deliver your products and services to. Who better to help U.S. entrepreneurs crack Europe than Europeans?

Global skills. The value of understanding foreign markets does not stop with Europe, though. Far too much of U.S.-originated innovation is born in the form of English-language, iOS-only apps with hard-coded dollar signs. European entrepreneurs, especially those from the smallest countries, are much better trained at operating globally in multi-currency, multi-cultural markets. As a proof point, look at how the likes of Finnish Rovio (Angry Birds) and Supercell (Clash of Clans) or Skypers in London or Tallinn and Evernoters in Zürich or Moscow have conquered the astonishingly tough Chinese and Japanese markets.

Security and privacy. In the post-Snowden days we’re living in, there is a new set of questions around the physical and legal location of users’ data and the regulations governing its privacy. Although the rules and behaviors driving this have been evolving in a U.S.-centric way thanks to U.S.-based Internet giants, if you look at where the users of the Internet live today, less than 10 percent of them are in the United States. And that share is declining.

It is obvious that nations other than the U.S. will have an increasing say in the governance mechanisms and regulation of the system with Europe at the forefront. And this is not just a government thing. The European tech scene can help its U.S. peers figure things out as private entities first.

If we Europeans can follow through with an approach of giving something unique and valuable, as opposed to just trying to get funding from the other side, I believe the European and Silicon Valley tech scenes have a shot at moving closer together. For U.S. players, this would presume paying a little bit more attention to the world outside. For Europeans, it’s mustering a bit more confidence in ourselves.

I am sure more non-financial bridges can be built. And as it has been shown by some VC investment-related research: Cold hard cash will eventually follow the international corridors where smart people are already on the move.

Sten Tamkivi has been a software entrepreneur for 16 years and spent the recent half of his career as an early executive at Skype in Tallinn, Estonia. Sten is now an Entrepreneur in Residence at Andreessen Horowitz. This story orginally appeared in TechCrunch.

-

Sten Tamkivi was the CEO and co-founder of Teleport.org.