One sunny afternoon this April, a Chinese teenager nicknamed Gallen was backpacking through Bali, hunting for things to do. But he didn’t turn to TripAdvisor for crowd-sourced suggestions (too time consuming) or scroll through Instagram for local geotags (too imprecise). Instead, Gallen enlisted recommendations from other nearby tourists through a WeChat group chat organized by the online travel provider Ctrip.

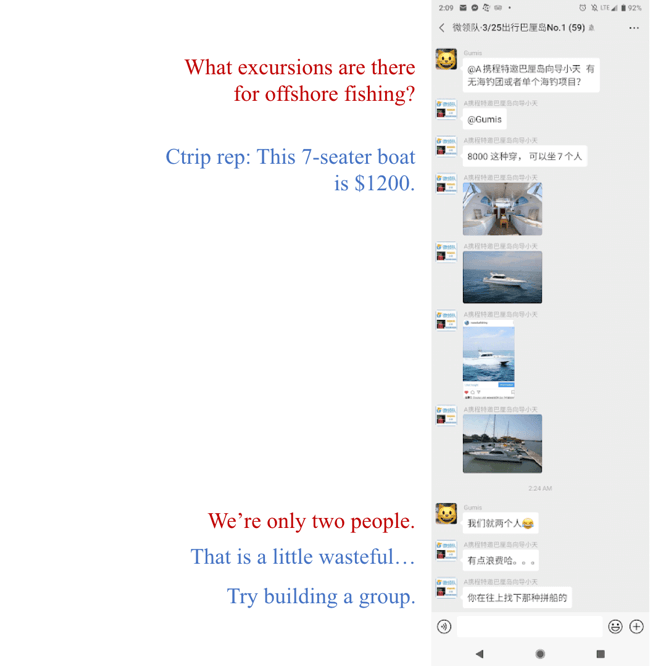

The Chinese company’s virtual-tour-manager program (VTM) uses WeChat group chats—populated by other Ctrip travelers in your destination city at the same time and overseen by a Ctrip representative—to provide a real-time concierge service. Through the group chat, Gallen ended up renting a car with a local Chinese-speaking driver and spending the day with other solo travelers at Pandawa Beach on Bali’s southern coast.

In early 2015, “conversational commerce” was hailed as the future of online shopping. Back then, the term was commonly applied to tech like shopping bots and voice assistants. But the subsequent rise of private messaging suggests that group chats may actually be the secret to turning conversations into commerce. Companies across verticals in China, including travel providers, gyms, edtech startups, and parenting groups, are all leveraging private group chats to build trust, interactivity, and community into their brand experience.

The shift from sprawling social networks back to smaller, more niche groups is becoming increasingly apparent in the US, as well. Even Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged the trend in a blog post this spring, noting, “We already see that private messaging, ephemeral stories, and small groups are by far the fastest growing areas of online communication.” But while group chats in the West are most often populated by our friends, China provides multiple examples of companies using group chats to facilitate deeper customer relationships and social commerce.

Turning trust into transactions

Brands have discovered that user trust is a crucial metric in turning a network into a transaction platform. (It’s one big reason Apple and Amazon have been able to expand into new revenue streams so quickly.) In the West, companies have adopted strategies like end-to-end encryption and real-name policies to reinforce a sense of security. In Asia, messaging platforms use a different set of tactics to build trust.

On WeChat, for example, group chats are discovered entirely by word-of-mouth or QR code—there is no global search option. The QR code is automatically disabled once a group reaches 100 members. Once the group grows to that size, users can only join if invited by a friend; groups are capped at 500. This means that even large group chats have a built-in social filter, since anyone who joins the group is likely the friend of at least one other existing group member. As a result, every group feels like a secret, known only to other members.

Cultivating a sense of safety is key. Unlike WhatsApp and Signal, which reveal users’ private cell phone numbers to the group– or the now-defunct chats within Facebook Groups, which exposed users’ real identities–WeChat allows its users to adopt aliases. Those anonymous usernames act as a privacy shield, giving users control over how their identities are displayed. (Though it’s hidden from other group users, WeChat does require a phone number and real-name verification to sign up, which curtails anonymous troll abuse.)

Another trust-building policy is truncating messages. Newcomers who join WeChat or WhatsApp group chats are unable to view any of the previous messages, which lends a semblance of privacy for existing group members.

Once brands have developed trust among users, they’re able to leverage these social networks into new revenue streams in a variety of areas.

Concierge Services

Customer service chat portals are already popular on modern ecommerce websites and can be easily implemented with third party software. But group chats on messenger apps can help transform traditional customer service into a crowd-sourced concierge service. Ctrip’s virtual tour manager, just one example, was used for 10 million trips in 2017 and 14 million trips in 2018.

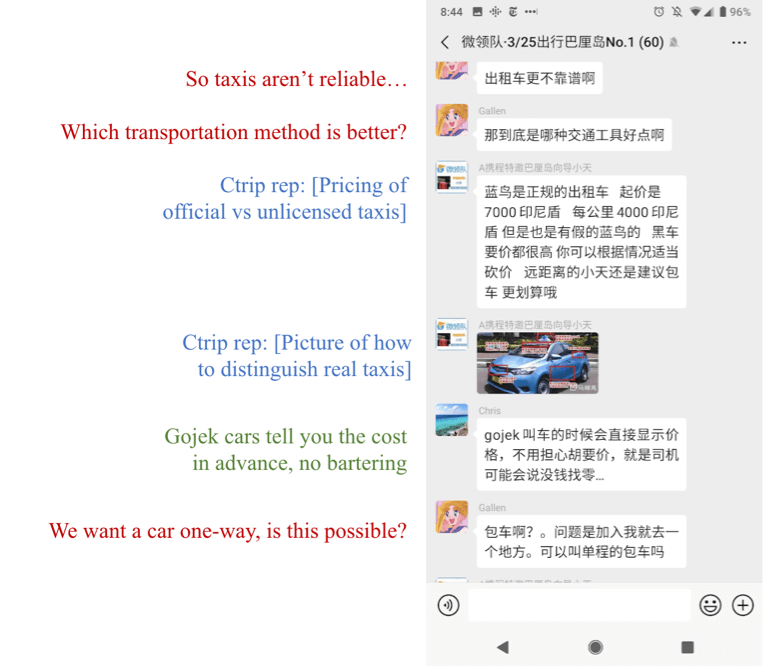

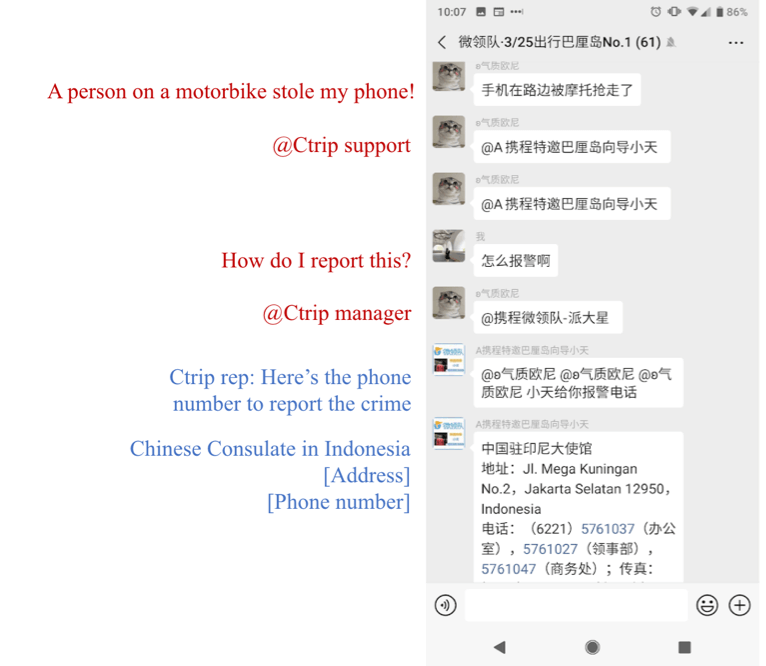

Common concierge requests in VTM group chats include airport pickup, drivers, tours, and spa and restaurant reservations. The group chat dynamic allows Ctrip to upsell services and share relevant information in a way that feels communal, rather than commercial. In addition, Chinese travelers get the reassuring perk of access to a bilingual service representative. During the Las Vegas shooting in October 2018, Ctrip used VTM to quickly locate its customers visiting Vegas and offer them flights home the following day.

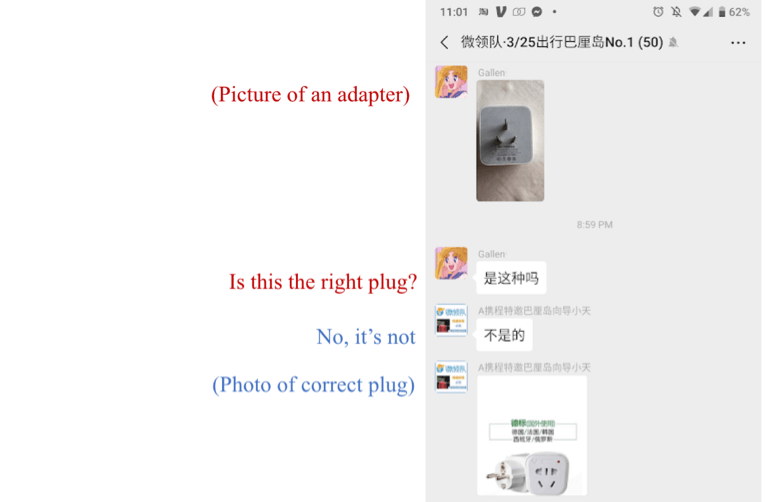

A traveler asks a Ctrip representative which electricity plug to use.

Another customer asks a Ctrip representative how to choose a local taxi. The rep replies with a photograph teaching the group how to tell official taxis from unlicensed ones.

When a traveler reports that his phone was stolen, a Ctrip representative replies with instructions on how to contact local police.

Classes

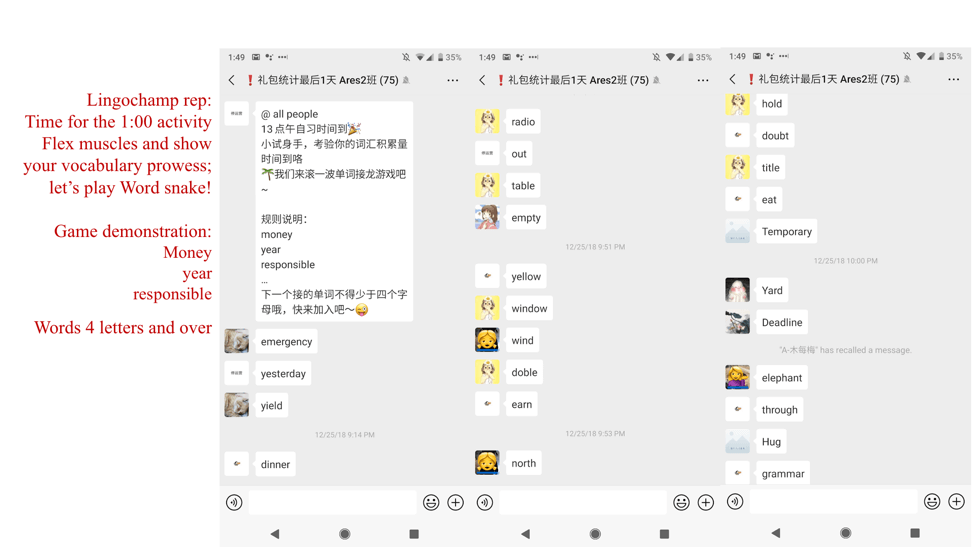

Academic and non-academic classes can use private group chats for student activities and peer motivation. AI-powered English learning app Lingochamp uses WeChat group chats to supplement its lessons. Upon purchasing a course, students are invited to join a WeChat group along with the instructor and roughly 100 fellow students. Each day, the instructor assigns a new activity, such as conducting mock interviews, studying song lyrics, or playing educational games like Word Snake (pictured below). Not only do these groups lend a social component to what is otherwise a one-on-one tutoring app, they also facilitate student relationships beyond the scope of the course.

A Lingochamp representative initiates a game of Word Snake among Chinese students learning English.

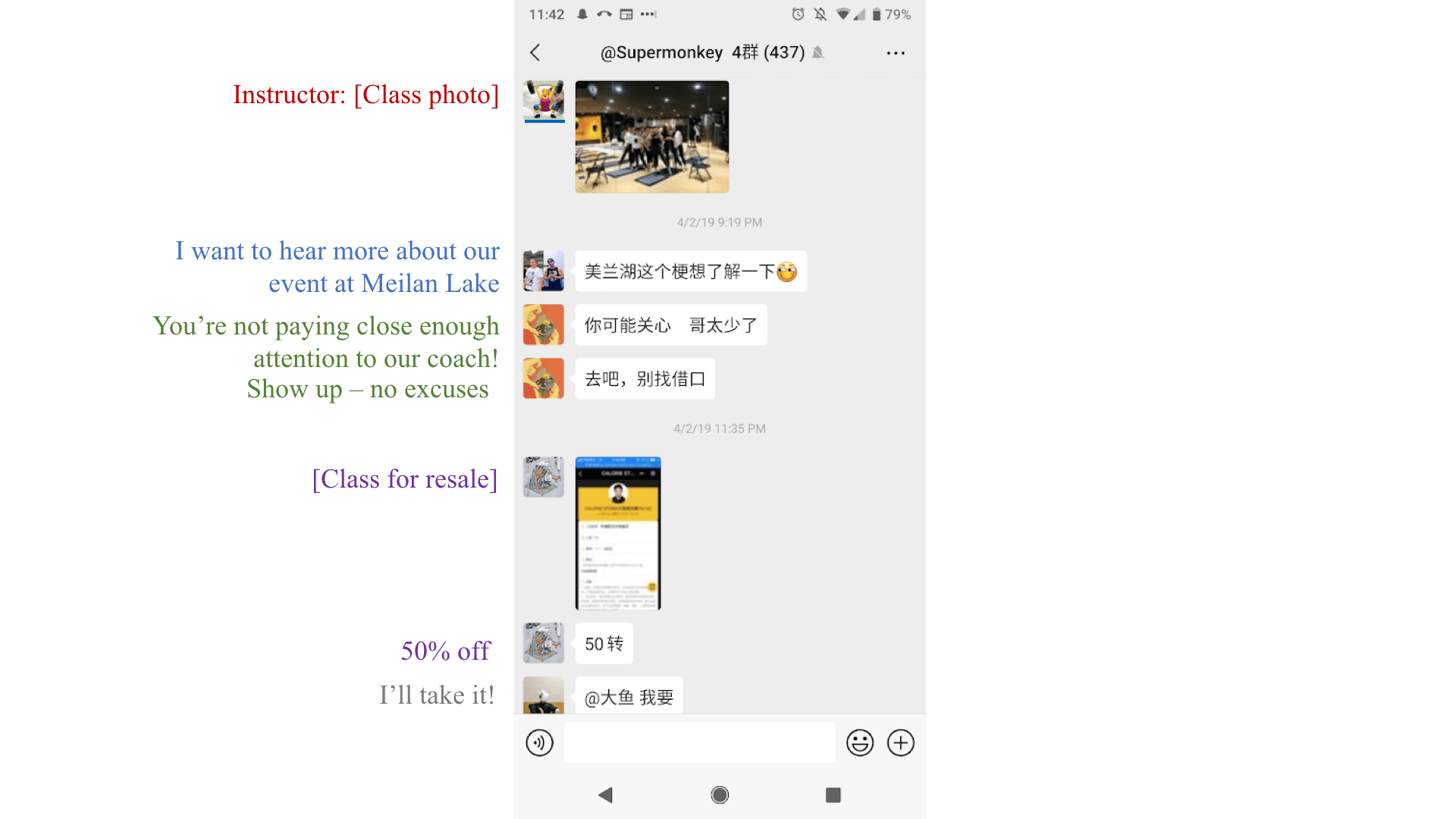

Similarly, Supermonkey, a network of tech-enabled gyms that has raised over $60M of venture capital, utilizes group chats to build offline relationships among gym-goers. When a user signs up for a Supermonkey workout class, he or she receives the instructor’s WeChat contact card and is added to the class’s chat group. There, Supermonkey instructors share social-media friendly class photos, nutrition tips, playlists, and more. Students also interact with one other—making plans to go dancing, reselling spots in upcoming classes, and chatting. Since Supermonkey does not require any monthly or annual membership, it relies on these “online classroom” groups for customer retention.

Gym-goers post photos, resell class passes, and send messages in a Supermonkey group chat.

Class-based private group chats are also gaining traction among businesses in the US. Lambda School, a San Francisco startup that provides online tech training at no up-front cost, uses Slack. Using the app, Lambda students can work together on projects and direct questions to fellow students or administrators. Other Lambda School Slack channels are intended to add long-term value beyond coding lessons: There are statewide groups to help students create offline connections; #career_help for career advice; and a motivational group called #hired where students post selfies and job acceptance letters. It’s not a coincidence that when co-founder Austen Allred was asked what Lambda School uses Slack channels for, he responded, “Literally everything.”

Consultations and Commerce

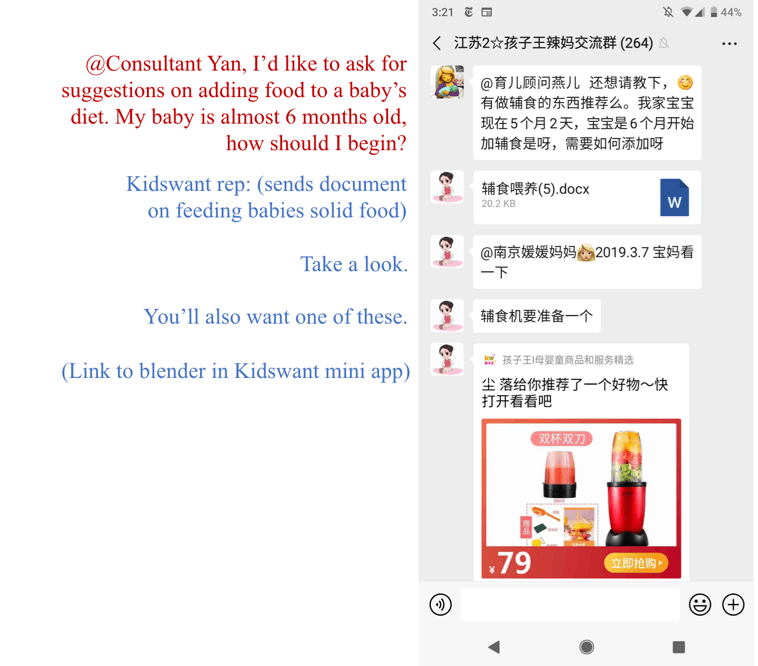

Sales representatives can be highly effective in persuading shoppers to make purchase decisions in physical stores. Some companies are exploring ways of bringing a similar experience into the home via private group chat. Kidswant, a maternity and kid-focused retailer that has raised over $55 million in venture capital, is an ecommerce company that has opened more than 250 physical retail stores in China. The company employs over 6,000 child care consultants, many of them former clinical nurses or professional caregivers, who often split their time between working in-store and answering questions online in private group chats. In-store consultants can add shoppers to Kidswant group chats, where parents might book private lessons or ask questions on topics ranging from breastfeeding to pediatric massage. The app recommends WeChat groups for nearby stores, so online shoppers are connected with other nearby parents. Consultants can also share promotion links and product reviews within the chat group.

In a group chat, a Kidswant consultant gives advice for introducing infants to solid food.

Similarly, Ctrip employees facilitate purchases for airport rides, Chinese-speaking drivers, boat rentals, and day tours in VTM chat groups.

The poster child for this form of chat-related commerce in China may be Pinduoduo, a group-buying business in which the unit price of an item becomes cheaper as more users purchase the deal together. Founded in 2015, the now public company has more than 366 million monthly active users. Pinduoduo’s dramatic growth came from leveraging WeChat group chats: to secure lower prices, netizens created shopping groups with friends and strangers for the purpose of sharing deals. Pinduoduo’s rapid ascent in the Chinese ecommerce space proves the merit of viral loops, especially when group chat sharing is part of the purchasing experience.

The next phase of “conversational commerce”

From chatbots to shopping via smart speaker, previous modes of conversational commerce have largely failed to live up to the hype in the US. But perhaps the reason is not that we are still waiting for next-generation technology; rather, we’ve been viewing commerce too narrowly, as an individual experience. Group chats set up by businesses don’t have to feel transactional; to users, such chats can feel more like interest groups than one-on-one sales pitches. They can provide community and crowdsourced knowledge in an organic way while simultaneously helping the brand behind them build trust and sell products.

Additional reporting by Avery Segal.