In 2006, LendingClub introduced a then-novel business model: the ability to offer online personal loans to millions of underserved customers. The peer-to-peer lender was a media and investor darling, hailed as a tech-enabled alternative to traditional banks. When LendingClub went public in 2014, it was valued at $8.5 billion, the year’s single largest US tech IPO. Now, five years later, that fintech pioneer has lost 85 percent of its market value.

Meanwhile, mobile upstart MoneyLion launched in 2013, also providing online personal loans—a direct competitor to LendingClub. Today, MoneyLion claims more than 5 million users and is valued at nearly $1 billion.

LendingClub had significant competitive advantages, from low customer acquisition costs—back then, personal loans keywords weren’t nearly as competitive on Google and Facebook was actively promoting LendingClub as an early F8 partner—to improved underwriting (the company provided lenders with access to customers’ credit score, total debt, income, monthly cash flow, and social data). So why is LendingClub experiencing growing pains while MoneyLion sees significant growth? Though the latter started out solely as an online lender, it quickly morphed into an all-in-one lending, savings, and investment advice app.

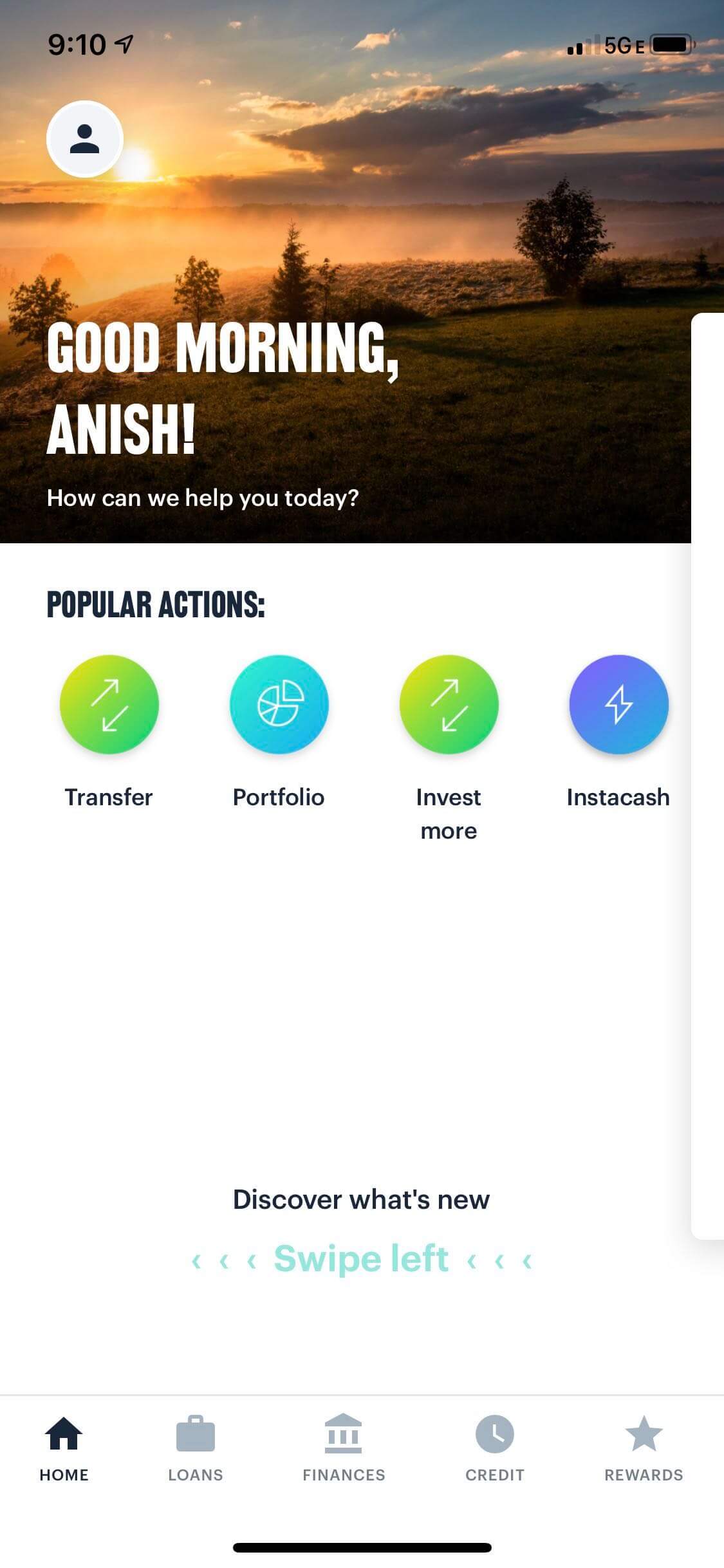

These competing companies illustrate the difference between facilitating a one-off transaction and an ongoing conversation around money. Much of first-wave fintech was narrowly focused on lending; the emerging model wraps lending into a spate of other value-added financial services. Today, the new consumer lending business doesn’t look like a lender: it looks like a swipeable financial assistant—what I like to think of as the “money button” on your phone.

Narrow services, fleeting advantages

Many of the trailblazing financial startups of the aughts were tech-enabled lenders. LendingClub, the most prominent of the bunch, was quickly joined by competitors like Prosper and Zopa. But in the increasingly crowded category of financial services, strong early growth does not necessarily equate to a long-term market position. That’s because giving people money is both easy and, from a business-building perspective, quickly forgotten—when a company extends a user a loan, it doesn’t necessarily mean that user will seek you out the next time they need cash. As a result, businesses primarily based on lending effectively need to reacquire customers over and over again. In the case of LendingClub, for example, the cost to acquire loans has risen over time (up 95% from 2013 to 2018) while, since 2018, revenue from loans has decreased 8%. It’s becoming more difficult—and more expensive—for the company to acquire customers.

Put another way, it’s easy enough to drive one-off transactions, like refinancing a student loan or borrowing money to make home improvements. But when that financial drudgery is complete, there’s little incentive for continued engagement. (If your mortgage lender started throwing parties, would you go?) In our view, the most sustainable companies will be lenders that provide ongoing value, giving customers a reason to stay.

The future of fintech: lending + services

A new wave of fintech startups understand that regularity and rhythm are the basis of any good relationship. Take Tally, for example, which is building a large-scale lending business via automating credit card payments. Or Earnin, which provides ongoing value by granting customers access to an earned wage advance, say, every two weeks. Credit Karma hooks users by offering regular updates on your credit score. The services these companies provide to users—conveniently packaged in app form—go beyond loans. And by driving continued engagement, these companies don’t have to pay to reacquire customers.

In addition, the business (in this case, providing or facilitating loans) actually improves the customer experience and the overall product. Credit cards are a classic example. By using them to make payments, the consumer earns rewards—improving the experience and the product—while the credit card company makes money via the interchange. Likewise, for Credit Karma members, taking a personal loan can reduce credit card debt, thereby improving their credit score. Another example outside fintech is Google Ads (formerly Google AdWords). When useful results are returned, it actually improves the utility of Google Search, giving consumers a reason to re-engage with the broader product. Thus, a flywheel is created between customer retention and monetization.

In the coming years, fintech companies will continue to duke it out for dominance in various core verticals, whether that’s financing a home, paying off student loans, or managing credit card debt. But the real test of who will own the money button on your phone will be in who can build enduring customer relationships. By being holistic, fintech companies can earn a place in users’ regular app rotation—then cross-sell into new product areas. Even as businesses like LendingClub and Prosper are losing ground, peer-to-peer lending remains a $138 billion market. The next wave of lenders, though? They’re pocket-sized financial assistants.