One of the first challenges I faced when I joined Credit Karma’s product team four years ago was adapting my more generalized product management experience to the specificity of fintech and financial services. In that first year, I learned (sometimes painful) lessons about the differences between building social products and building fintech products for consumers.

Now, as a fintech-focused investor, I’ve become attuned to these nuances when evaluating the probable success of fintech products. In the ensuing years, we’ve seen fintech move from a specialized vertical, like lenders and challenger banks, to a more generalized horizontal (every company is a fintech company). Product leaders across many categories—from Uber to Google—are looking to adopt banking, lending, payments, and more. I’ve previously described this trend as a race between consumer companies trying to build financial services and financial services providers trying to build consumer products. But while many are now exploring fintech applications, the dynamics of building such products are unique.

Want more a16z?

Sign up to get our best articles, latest podcasts, and news on our investments emailed to you.

Thanks for signing up.

In my deep dive into financial services as GM of consumer products at Credit Karma, I developed a set of questions that helped us hone the intent and design of the product and shape the user experience. That framework ended up inspiring many helpful conversations and vastly improved the quality of our output.

Here are the three questions that every fintech product manager should be asking themselves.

Who is this for?

Can we uniquely segment our audience by credit bands, income, or another uniquely identifiable trait?

Every product manager knows that having an innate understanding of the customer is central to the product’s success. What’s less understood is the unique segmentation of customers in financial services.

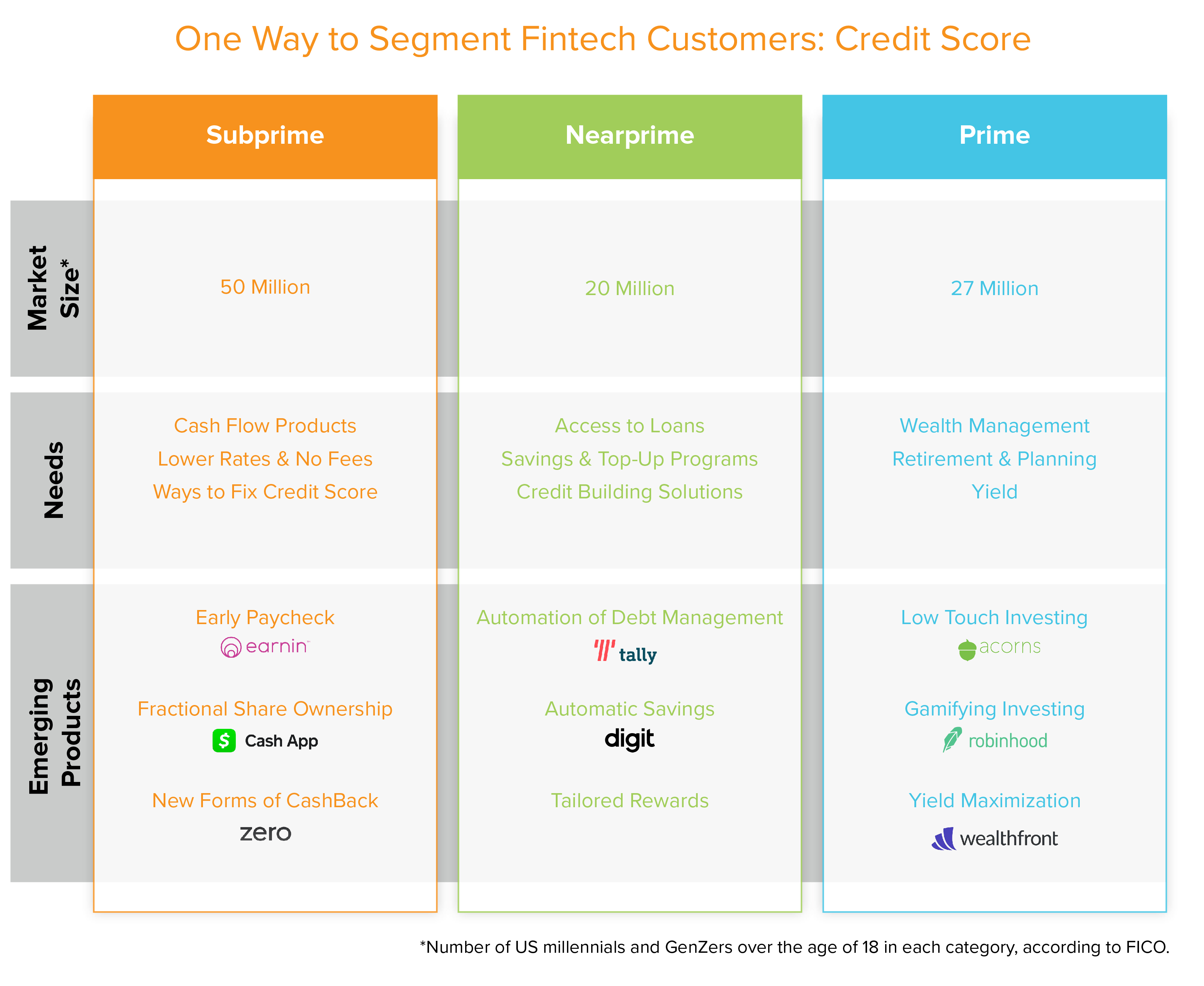

The best proxy I’ve found for these unique segments is credit score bands, usually defined as super-prime (760+), prime (720-760), near-prime (640-720), and subprime (640-). Though credit scores are woefully limited in some respects, credit reports do provide a useful proxy into income volatility (in that no one intentionally misses a payment) and the amount of credit that’s been extended to the consumer in the past (a measure of one’s ability to pay).

There are two benefits to this approach. First, it allows you build a simple model for each customer segment’s core financial needs: subprime has the most potential for income volatility and cash flow needs, near-prime has mixed access to credit and term loans (and it’s usually expensive), and prime consumer have the most choice, confidence and access to credit. The other benefit to categorizing your audience in this way is that it’s easy to uniquely target these consumers—you can easily A/B test product features and marketing messages to these segments.

A similar “grouping” approach can be taken with income and other financial attributes. The key idea here is that not all consumers have the same financial pain points. Users’ needs, wants, and attitudes toward money are driven by the past and present: their current means and their financial history. Product managers should look to segment potential customers and tailor products to them, accordingly.

Will they love it?

Most product managers mistakenly focus on functional outcomes. It’s actually much easier to impact users’ cognitive and emotional outcomes.

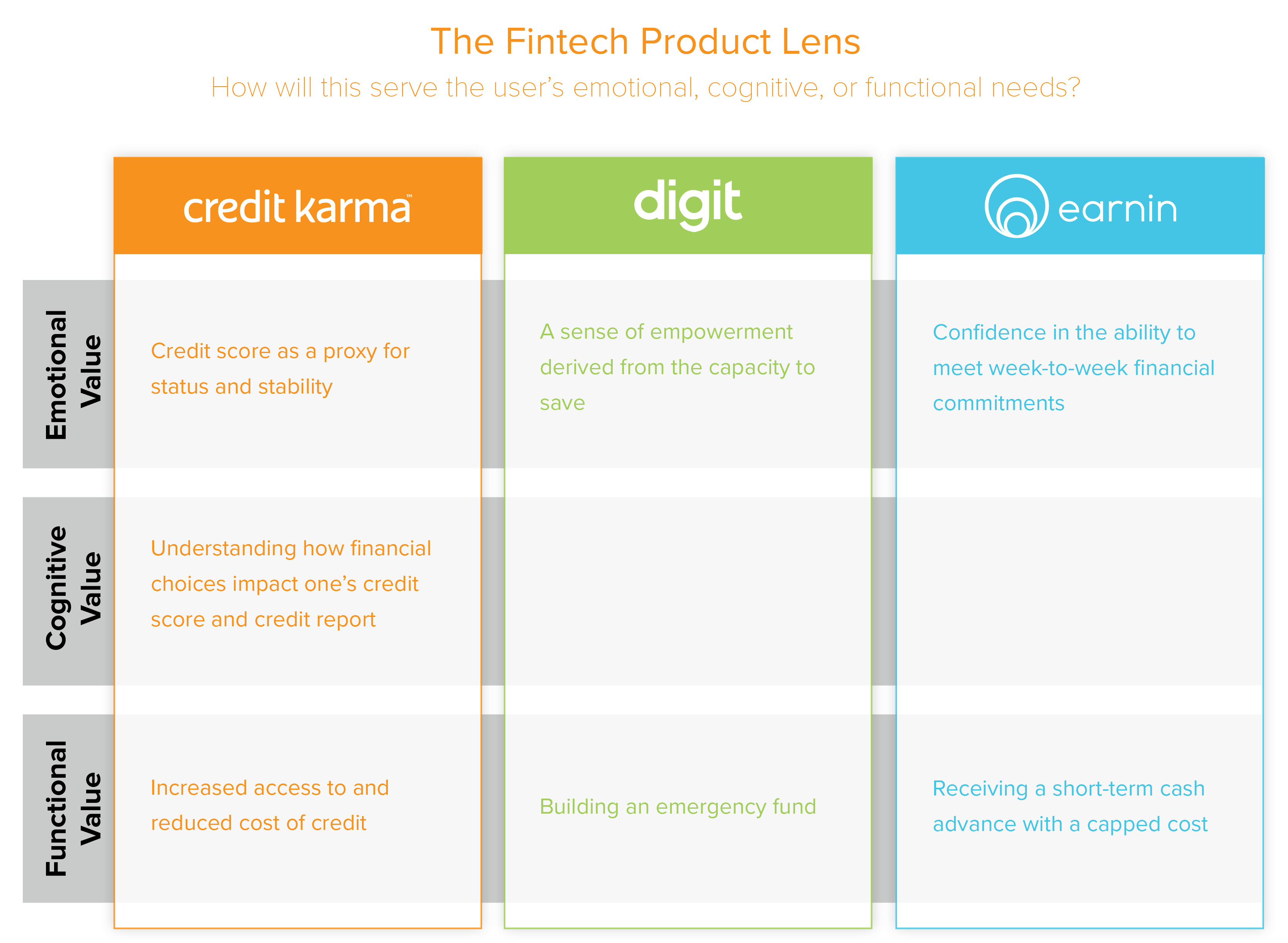

I’ve adopted a simple framework inspired by Sachin Rekhi’s Hierarchy of User Friction: How will this feature serve the consumer’s emotional, cognitive, and functional needs? Here are the differences:

- Emotional: I feel better about an aspect of my financial life.

- Cognitive: I better understand an aspect of my financial life.

- Functional: I see tangible change in my financial life, such as more money, less expensive debt, or better credit.

Though we aspire to drive functional outcomes for all consumers in fintech (wouldn’t it be amazing if everyone in America could have more money in their pocket!), that last category—the appreciable result—is usually the hardest to impact. Why? Many of these functional solutions require fundamental behavior change, increased earning power, or rewriting the past. Instead, PMs should assess how they can help consumers better understand and feel in control of their money.

In the case of Credit Karma, for example, curiosity is one of the top reasons consumers try the product. And one of the top reasons they return to the product is that credit score has become a proxy for status and a reflection of one’s stability—it’s an independent measure of how well you’re “adulting!” Both of these drivers are largely emotional. This provides a useful lens through which PMs can assess nascent products.

Will they be surprised?

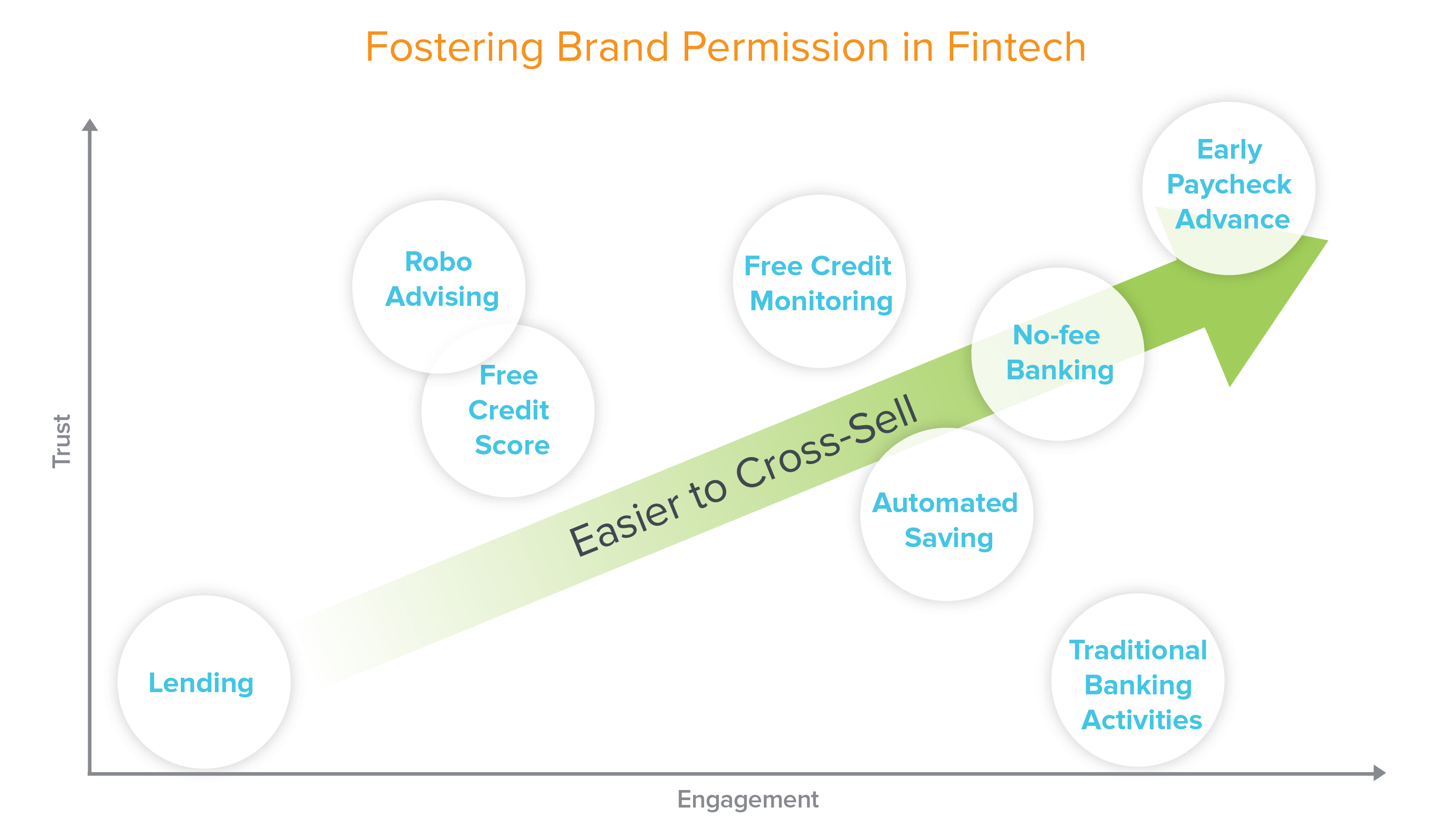

Brand permission and brand stretch are key concepts, particularly as non-fintech companies like Apple and Google start offering banking products and fintech companies pursue the concept of self-driving money.

Though consumer attitudes toward online financial services are changing (remember how insane it seemed that people were giving Mint their bank credentials?), fintech products still face a higher bar for adoption than other types of consumer internet products. After all, this is your money. For that reason, product managers should be asking themselves, “How much of a stretch is it for our brand to be offering this service?” Relatedly, “How much brand permission do we have?” Essentially, this boils down to customer trust. Brand permission is accrued when you make (and keep) a set of promises to a consumer, then deliver on that commitment long-term. That typically occurs when a product has high engagement and drives financial progress for consumers:

Put another way: will consumers give your product the benefit of the doubt? A company like Apple has tremendous brand permission. Thus, when Apple offers a credit card—even though it’s a marked departure from previous products—its customers are willing to give it a try. Conversely, it’s not a stretch for Wells Fargo to offer robo-advisory services. But consumers are currently so distrustful of the brand, given its recent shenanigans, that they’re likely to be reticent in trying a new product offering.

A product manager’s guide

Having worked as a product manager in a range of consumer categories, fintech is both the most promising—in terms of its macro, life-changing potential—and the most fraught. To succeed in fintech requires having a laser focus on your particular subset of customers. Being naive to the distinct dynamics of a particular industry can needlessly burn a lot of engineering cycles. It’s important to identify the pain point you’re solving for, whether that’s emotional, cognitive, or functional (or, in a rare jackpot, all three). And perhaps more than any other industry, financial services companies are predicated on the ability to build brand trust and boost engagement. It’s a high stakes, high reward endeavor. These three questions will help you refine your focus—I hope they’ll be as helpful to you as they have been to me.