Conventional wisdom holds that passive trading is the rational investing strategy. Active traders are often portrayed as gambling rubes or lucky opportunists who will (eventually) be handily beaten by index funds. But the steady growth of platforms like eToro and Robinhood, coupled with the acceleration of investing communities like WallStreetBets, has tipped the power from institutions back to individuals and created a renewed interest in active trading.

The internet has always aggregated fringe behaviors; now it enables individuals to coordinate trading strategies in a way that was previously only possible through institutions. That technological shift, coupled with cultural upheaval—thanks to a combination of loose monetary policy and an uncertain economy, younger Americans’ path to financial progress is steep—has catalyzed a lean-in mindset around investing, particularly among Gen Z.

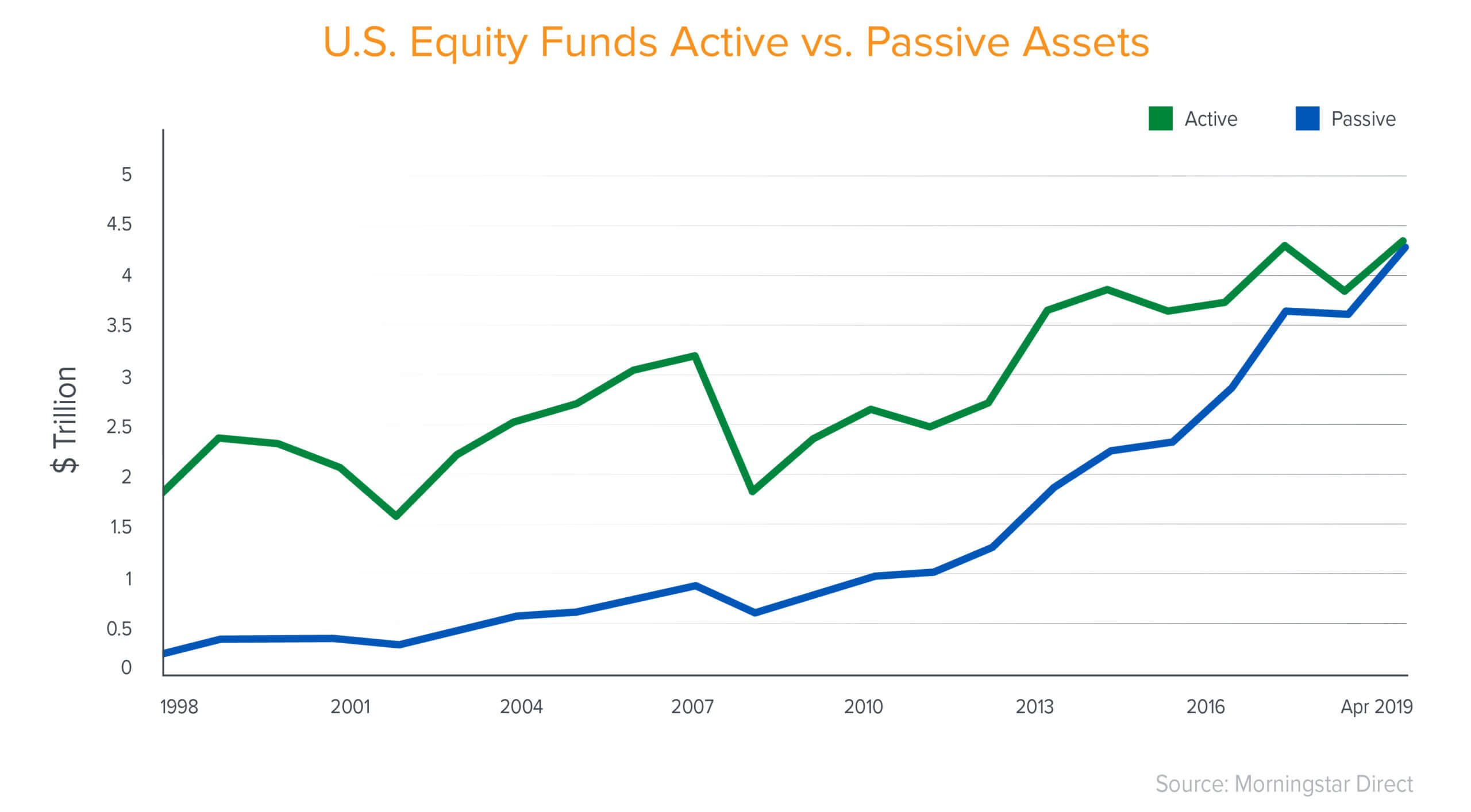

This is a relatively new phenomenon. Passive investing first became part of the American investors’ portfolio in 1976, when John Bogle, then the CEO of Vanguard, launched a new type of investment vehicle called an index fund. Bogle created the Vanguard 500 Index (VFINX), which would track the S&P 500 and allow retail investors to buy a basket of stocks that represented the market—without buying every single stock. Genius! Though it wasn’t the first vehicle of its kind, what Bogle had invented was a publicly available index fund. He became a major voice in evangelizing this new type of “smarter” investing. Since then, innovations like low-cost mutual funds and the diversification of index funds (to track all types of indexes and baskets) have made passive investing increasingly common among retail investors. In September 2019, passive equity funds overtook active investing for the first time.

(Charts provided herein are for informational purposes and should not be relied upon when making an investment decision.)

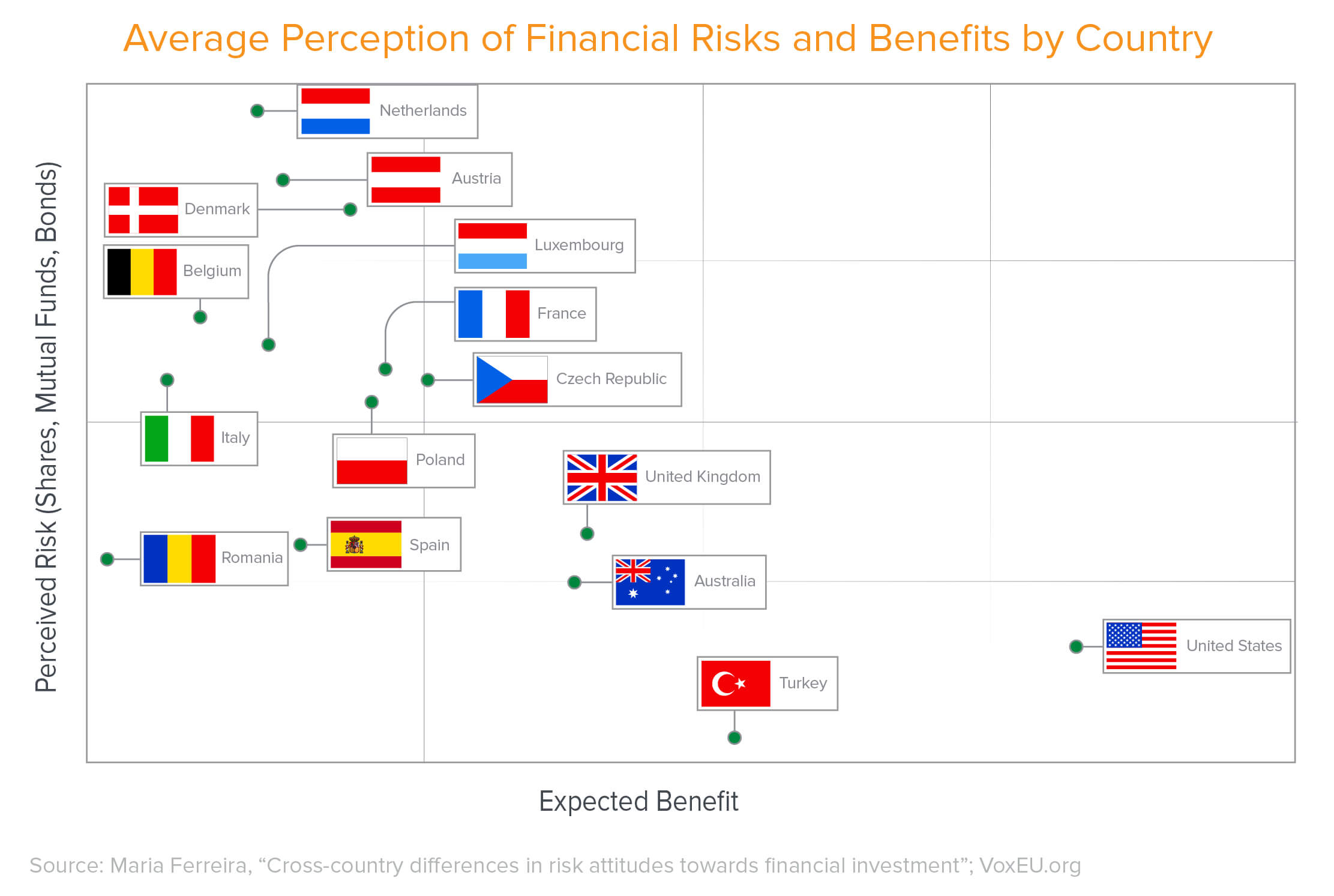

(Charts provided herein are for informational purposes and should not be relied upon when making an investment decision.)

However, in recent years we’ve seen momentum start to shift back towards active investing. The status-quo—passive-only investing strategies—is being challenged by newer generations of investors entering the market. The reasons behind this shift are part psychological, part structural.

First, American psychology and attitudes around money are changing. A combination of illusory superiority bias—the belief that we are more financially savvy than we actually are—and a culture of financial optimism leads most retail traders to believe they have above-average trading ideas and strategies. (This, of course, is contradicted by proponents of passive investing, who point out that active strategies underperform passive ones in returns especially when accounting fees.) In part, the psychology of American exceptionalism extends to active trading.

In addition, Gen Z faces an uncertain path to financial progress. A combination of asset price inflation (QE and COVID stimulus packages) and generally loose monetary policy has driven the transfer of wealth from the asset-poor (young) to the asset-rich (old). A new generation of Gen Z investors are willing to take risks to counter a deck that may be stacked against them. Active investing is a natural extension of hustle culture, in which risk is embraced and failure is accepted (and even celebrated); YOLO behavior on WallStreetBets is just one example. Furthermore, Gen Z retail traders have never experienced a market contraction—the oldest of them were 10 in 2007 when the S&P began its 50 percent decline. For many, passive investing is viewed as a strategy for the already rich to *stay* rich, not for those wanting to *get* rich.

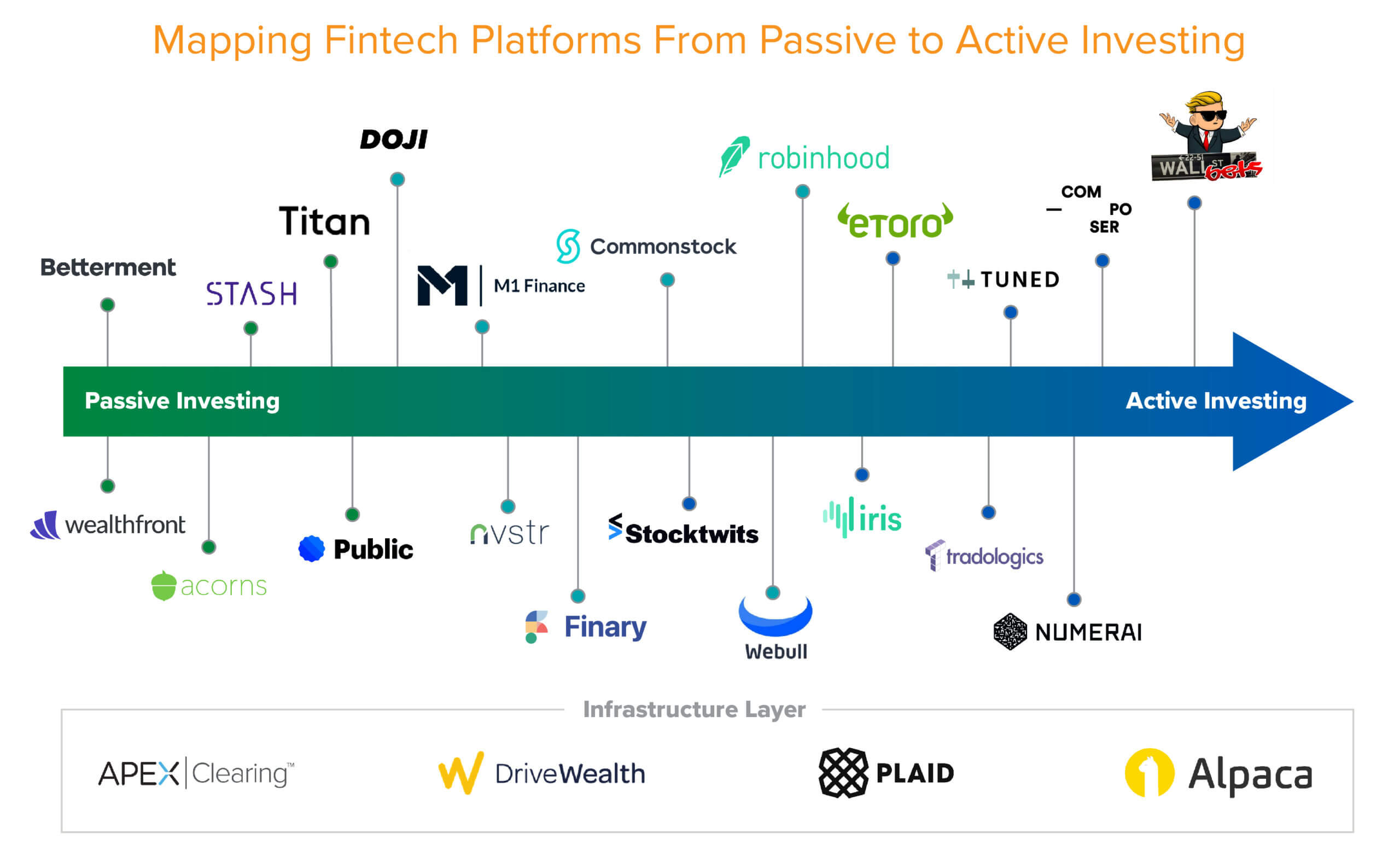

Beyond the psychological forces driving younger active traders, part of the fuel is structural. Innovations in infrastructure have lowered the barriers to entry for retail investors. No-fee trading was first introduced by Robinhood in 2013; only recently have large brokerages like TD Ameritrade and Charles Schwab eliminated their fees, opening up equities to all investors. Similarly, the rise of fractional investing through companies like Acorns and Stash has enabled investors to participate in the market with as little as $10 or less, which was previously unimaginable. Finally, brokerage-as-a-service platforms like DriveWealth and Alpaca allow existing apps and new investing platforms to offer brokerage capabilities to their users.

As a result, we’re seeing of four types of active investing emerge, supported by a growing set of dedicated tools:

Distributed hedge funds

In the old world, the best investors worked on Wall Street, executing their strategies behind the balance sheets and research departments of hedge funds and banks. Now, individual retail investors can share and coordinate their own research, trading strategies and collective balance sheets to match the sophistication and scale of these hedge funds.

These investors can post a trade idea and others can register their approval with their dollars, all verified through proof of trade. Status is conferred by correctly predicting outcomes, and in the future, incentives could align through shared economics (say, 20 percent carry for the community). Trades could even be coordinated in participants’ accounts, so capital wouldn’t have to be pooled; software would facilitate “voting” on trade ideas and execute those trades. Previously, only hedge funds had the access and capital resources to deal in this type of trading. Through communities like WallStreetBets and execution layers like Numerai, that coordination is becoming more distributed.

Individuals as institutional scale asset managers

Wall Street has always had star stock pickers. The internet version of this phenomenon is the unbundling of indexes—enabled by platforms like Apex and startups like Doji—and the ability for anyone to follow in the footsteps of Cathie Wood and create new ones. A truly efficient market means the best ideas should attract the most capital. In the past, people have mostly flocked to ETFs from name-brand funds like Vanguard Funds and Fidelity Index Funds. But in the future, retail traders will follow individual investors that align with their investing style and return profile. eToro’s copy trade approach in crypto and Doji’s “create your own ETF” approach are just two versions of what this might look like.

Low-code trading IDEs

Just as Github and Figma provide collaborative environments for programmers and designers, there are now a number of emerging collaborative development environments for hobbyist and prosumer quants. With a “Github for investors,” the best managers in the world could build a public record of successes and participate in the economics of fellow investors that leverage their primitives. Whereas this was previously only happening among quants in banks and hedge funds, now new tools and increased consumer interest are extending this capability to the masses. Composer, Tuned, and Tradologics have started to build early examples of developer-first trading platforms.

Bottoms-up communities

In the past, investing conversations were largely fragmented through #fintwit, Discord channels, YouTube, and group chats. But through Stocktwits, WallStreetBets, Commonstock, and more, investing communities are becoming increasingly centralized. The integration of proof of trade and trade execution has also provided much needed transparency, differentiating the current generation of communities from past efforts like Cake Financial. The infrastructure exists to open up trading data and put it at the forefront of new social platforms.

Those who chalk up the recent rise in active investing to a bull market miss a number of structural catalysts behind it. The psychology of American exceptionalism, coupled with a challenging path to financial progress for Gen Z, are two of the largest cultural drivers. Those factors, coupled with recent technology shifts, portend that active investing is here to stay. In short, retail portfolio theory—buy and hold for 30 years—is being replaced by new investing approaches, including bottoms-up communities and zero-cost passive investing. We believe that in the years to come, active strategies will have a place in every retail investor’s portfolio.

* * *

-

Anish Acharya Anish Acharya is an entrepreneur and general partner at Andreessen Horowitz. At a16z, he focuses on consumer investing, including AI-native products and companies that will help usher in a new era of abundance.

-

Matthieu Hafemeister Matthieu Hafemeister is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz focused on early stage fintech investments. Matthieu joined the firm in 2017. He first spent time on the a16z Corporate Development team, working on late stage investments across verticals and helping portfolio companies raise downstream capit...