How do you scale from a scrappy, early-stage startup with a handful of employees to a growth-stage company with hundreds, or even thousands, of employees? Hire the right executives. These first principles lay the foundation for making those key hires.

Once your company has a product that customers want and a go-to-market strategy to get it to them, you’ll face a new set of challenges: scaling operations.

Finding product-market fit in the early stages of a company’s development usually comes from the vision, creativity, scrappiness, and resilience of the founders and first employees. Founders are involved in most hiring decisions, and the organization tends to grow linearly. Once a company finds product-market fit, however, you’ll often need to ramp up business and operations exponentially to continue delivering value to customers.

Building your executive team is one of the most important elements of effectively scaling in the growth stages. People often talk about growth-stage companies in the context of pre-IPO companies. While this guide does cover IPO considerations, it defines growth-stage companies more broadly as companies who have found product-market fit and are now scaling. The limiting factor in how quickly you can scale is typically how quickly you can ramp up hiring. The best growth-stage executives serve as beacons for talent. They quickly tap their networks to build out entire teams and functions, and then they help develop the organizational processes and structure to effectively lead those teams.

While hiring new executives is almost always necessary during the growth stage, that doesn’t mean you’ll up-level your entire leadership team once you find product-market fit. Your existing team has often built the company and its culture from the early stages, and some of these leaders will be able to grow with the company, helping to scale that original culture by building loyalty and providing continuity and organizational context as you grow.

How, then, do you figure out which executives you need to hire, and how do you make the right hires? It’s not an easy question to answer. Even when you know the hire you want to make, you still have to recruit and retain an executive who is very likely in high demand. Not surprisingly, executive hiring takes up a significant amount of most CEOs’ time. Even so, almost every growth-stage company will hire executives who don’t work out. Mishires usually result from misdiagnosing what’s needed from an executive, and they’re costly mistakes to correct.

We put together this playbook—based on decades of Andreessen Horowitz operating team expertise—to share the best processes and tools for hiring executives to scale your company from product-market fit through IPO. In later sections, we’ll cover the executive hiring process, executive compensation at growth-stage private companies, and tips and best practices for hiring and onboarding some of the most common executive roles.

First, though, we lay out our first principles for executive hiring.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Conduct no more than 2 executive searches at a time

TABLE OF CONTENTS

In our experience, the average executive search takes 130 days. Though a good hiring process can expedite this timeframe, hiring a top-tier executive will still take substantial time and resources. A CEO can only effectively conduct 2 executive searches at the same time. In some scenarios layering on a third might be necessary, but only if 1 of the other 2 searches is in good standing or coming to a close. You may have 7 hires you want to make, but you simply can’t run multiple executive searches at one time without grinding other work to a halt or setting yourself up to make suboptimal hires.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Hire for what you want to accomplish in the next 12–18 months

TABLE OF CONTENTS

People often think about the executives they’re hiring and is this person going to do anything for 4 years, or 5 years, or 6 years; I think that’s not always the right question to ask. In fact, I had a board member once—Dave Strohm, who was a mentor to me, I think of him as the Yoda in my life—and he once said an expression that I’d never heard before, ‘horses for courses.’ It’s sort of an archaic expression. In horse-track racing, there’s like dirt courses, there’s grass courses… And you want to run the right horse for the right course.

—David Ulevitch on the a16z Podcast: What Time Is It? From Technical to Product to Sales CEO

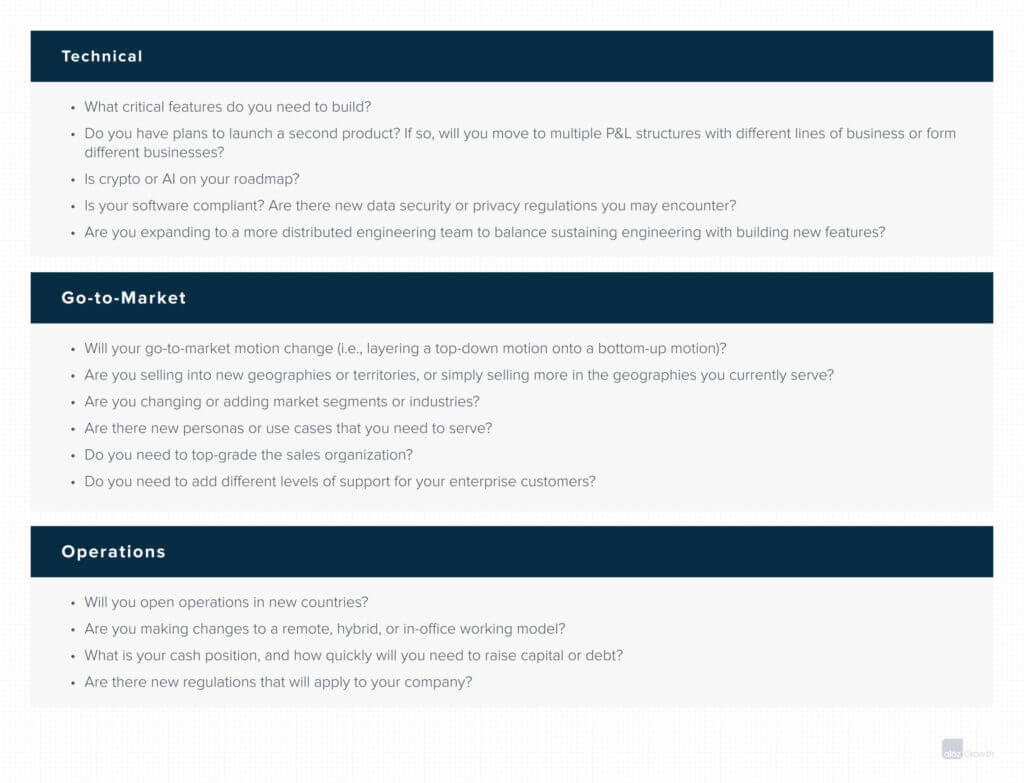

While executive hiring follows some general patterns,* those patterns are more useful for understanding the broader talent landscape than for figuring out your specific hiring priorities. Your hiring priorities will depend on the strengths and weaknesses of the current leadership team and your goals for the next 12–18 months, not on hitting a particular revenue milestone or fundraising series.

Sometimes figuring out the gaps in your business may mean realizing that someone else is better equipped to own a particular function than you are. That may be easy to stomach when you’re a technical founder hiring a finance leader—but harder if you’re a technical founder bringing in a product leader.

We recommend that the CEO update the board on the health of the executive team and organization at least annually. This will help establish a cadence of reflection about what is and isn’t working and inform your hiring priorities. When looking at your current executive team, it can help to articulate: What are your business priorities in the next 12–18 months? What are the critical gaps or needs that you have around those priorities? And what executive roles might be most helpful in addressing those gaps?

Moreover, different executives often excel at different stages of growth. A common failure mode is hiring a great executive at the wrong stage. For instance, in the early stages of growth, you may need a head of engineering who can rapidly scale hiring for work on a single product. By the later stages, you may need an engineering leader who can manage a series of director-level reports and engineering efforts across multiple products. The more precisely you can identify your needs for the next 12–18 months, the more likely you are to hire the right executive at the right time.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Organizational structure and executive hiring go hand in hand

TABLE OF CONTENTS

To level-set about organizational structures more broadly: the bigger your company gets, the more difficult it becomes to maintain close communication, establish a shared context, and facilitate quick decision making. Your organizational structure is the communications architecture of your company, and getting the right structure in the right place at the right time gives your teams the resources and context they need to make good decisions. Org structures evolve as companies scale, and by the time you’re bringing on C-suite executives at the growth stage, chances are you’ve cycled through a few different structures. As new executives come on board to help the company reach new levels of scale, you might need to adjust your existing org structure in order to set up those new executives to tackle whatever problems they need to.

But there’s no silver bullet to designing org structures. To quote Ben Horowitz: “the first rule of organizational design is that all organizational designs are bad. With any design, you’ll optimize communication among some parts of the organization at the expense of others.” As a CEO, then, your job is to understand who needs to communicate and what decisions need to be made in order to address the particular problem you’re trying to solve. This generally involves making some tough tradeoffs. For instance, let’s say you’re bringing on a senior vice president of engineering to lead your move to a multiproduct structure. This raises the question: do you organize your technical teams as business units with separate P&Ls or as functional teams? The former allows those teams to move quickly but can often result in a disjointed experience for the customer, whereas the latter can make it easier for the entire team to understand what they’re building and why—but can also require teams to get buy-in from more cross-functional teams, which, in turn, slows down shipping rates.

In some cases, shifting the org structure when a new leader comes on board can be relatively simple. In an effort to move your legal function in house, for instance, you might bring on a general counsel and create a net-new legal team or department. In other cases, however, you may up-level a role, and the functions that currently sit with other leaders may now report to someone new. For example, if you have a COO who currently oversees legal, finance, and customer success, but you decide you need to bring on an experienced CRO to help ramp up top-down sales, you may need to prepare the COO that customer success will report into the new CRO.

Artificial intelligence and org structures

With the unprecedented rise of ChatGPT, generative artificial intelligence, and AI more broadly, many companies are figuring out how to best implement these tools in their company. Even if you aren’t building an AI product, AI is likely to have an impact on how your teams work. An emerging consideration for effective org design is where and how to integrate AI to both augment and automate how humans work.

The biggest gains won’t come from simply using AI, but by designing org for human-plus-AI workflows. As of this writing, we’ve heard from growth CEOs who have already started to see massive gains in engineering productivity and automated portions of customer support by effectively architecting AI into their org structure. However, these use cases aren’t simply about giving ChatGPT to your engineering or support teams. In some cases, companies are building their own language learning models (LLMs). In others, they’re fine tuning existing LLMs for their use cases, with an eye to AI architecture that effectively puts humans in the loop and org structures that effectively integrate AI.

Let go or level?

Sometimes the organizational changes that come with an executive hire will require letting go or leveling a current leader. In the best-case scenario, an early-stage leader will recognize that working for a more senior executive is an opportunity to learn from a tried-and-tested operator at the next level of scale. However, even if you outline your reasoning perfectly, an existing leader may opt to leave rather than be leveled.

Letting people go who helped you build the company is hard, but keeping people around to manage teams beyond their current skill level is one of the worst things you can do for your company. It may be tempting to think that you can mentor an existing leader who isn’t cutting it and help them grow into the role, but the sad truth is that it’s a bad use of your time and theirs.

Keeping a leader who isn’t cutting it risks diminishing the quality of their team’s work, increasing attrition, and establishing a pattern of people circumventing the substandard leader to get work done. At the very least, these leaders slow your growth. In the worst cases, these leaders take a negative toll on the broader culture and become an existential risk to the company. When your company has outgrown a leader, you owe it to your company to bring in the leadership you need.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

The CEO should lead the hiring process

TABLE OF CONTENTS

While you will work with a human resources team and possibly a search firm to build out your talent pipeline, you can’t outsource your role as the company’s leader in attracting, vetting, and ultimately deciding on new leadership because:

- No one knows your company better than you do. The initial conversations with a potential hire set the tone and scope of their role. If you aren’t involved in actively leading that conversation, you risk misdefining or miscommunicating the company’s needs and hiring someone who is the wrong fit.

- No one will sell a company to a tier 1 executive better than you, the CEO, will. Top candidates have plenty of options, and hearing directly from the CEO signals to them how important the role is to you and to the company.

- You signal the importance of the role to the rest of your organization. Internally, your involvement signals the executive’s role and function as an important priority. Especially when an executive role comes with org changes, this primes the org for change and makes it easier for a new executive to ramp up.

Change is unavoidable when a company seeks to scale. As Peter Senge, a senior lecturer at the MIT Sloan School of Management and founder of the Society for Organizational Learning, puts it: “Leadership in a learning organization starts with the principle of creative tension. Creative tension comes from seeing clearly where we want to be, our vision, and then telling the truth about where we are, our current reality. The gap between the two generates a natural tension.”

Provided there is a great vision, as a company enters the growth stages, the CEO must set a clear direction with objectives and measurable or quantifiable outcomes. Taking the company from early-stage vision to growth-stage reality requires hiring functional leaders who come equipped with a talent network as well as proven processes and systems to help build and measure results. These leaders will ultimately carry the company through the transition.

Building this executive team and navigating the resulting change is one of the most important—and often one of the loneliest—parts of the CEO job. But as tough as some of the decisions may be, hiring the right executives at the right time can transform your company.

Next, let’s look at The Hiring Process.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Further reading

TABLE OF CONTENTS

We’ve drawn insights from some of our previously published content and other sources, listed below. In some instances, we’ve repurposed the most compelling or useful advice from a16z posts directly into this guide.

Hiring Executives: If You’ve Never Done the Job, How Do You Hire Somebody Good?, Ben Horowitz

How do you hire people who are better at their jobs than you are? Know what you want, run the right process, ask the right questions, assemble the right interview team, and do your due diligence when it comes to reference checks.

What Time Is It? From Technical to Product to Sales CEO, a16z podcast with David Ulevitch and Sonal Chokshi

Nothing is straightforward about running a company. Any change you make will inevitably affect something else. So how do you know which knob to turn and at what time? Here, Ulevitch offers insights into building the right team for your stage of growth.

The Sad Truth About Developing Executives, Ben Horowitz

Is it your job as a CEO to develop your executives? According to Horowitz, the answer is a resounding no. Here, he outlines 6 reasons why being a functional manager can be detrimental to your job as well as ways that you, as a manager, can help your executives succeed.

*A Practical Framework for Scaling Your Executive Bench, Michelle Delcambre

This is one of the better breakdowns we’ve seen about scaling your executive bench. This article maps out data points from 30 outlier companies’ executive benches after each funding round over a period of 10 years.