Creator economy is a buzzy, often catchall term used to describe independent contractors. But in reality, most of the innovation has revolved around passion-project content (Substack for writing, Teachable for courses, etc.) and niche side projects. To date, “creator” tools have largely been quasi-horizontal, designed to serve broad categories of largely creative pursuits: writing, podcasting, course creation, and the like.

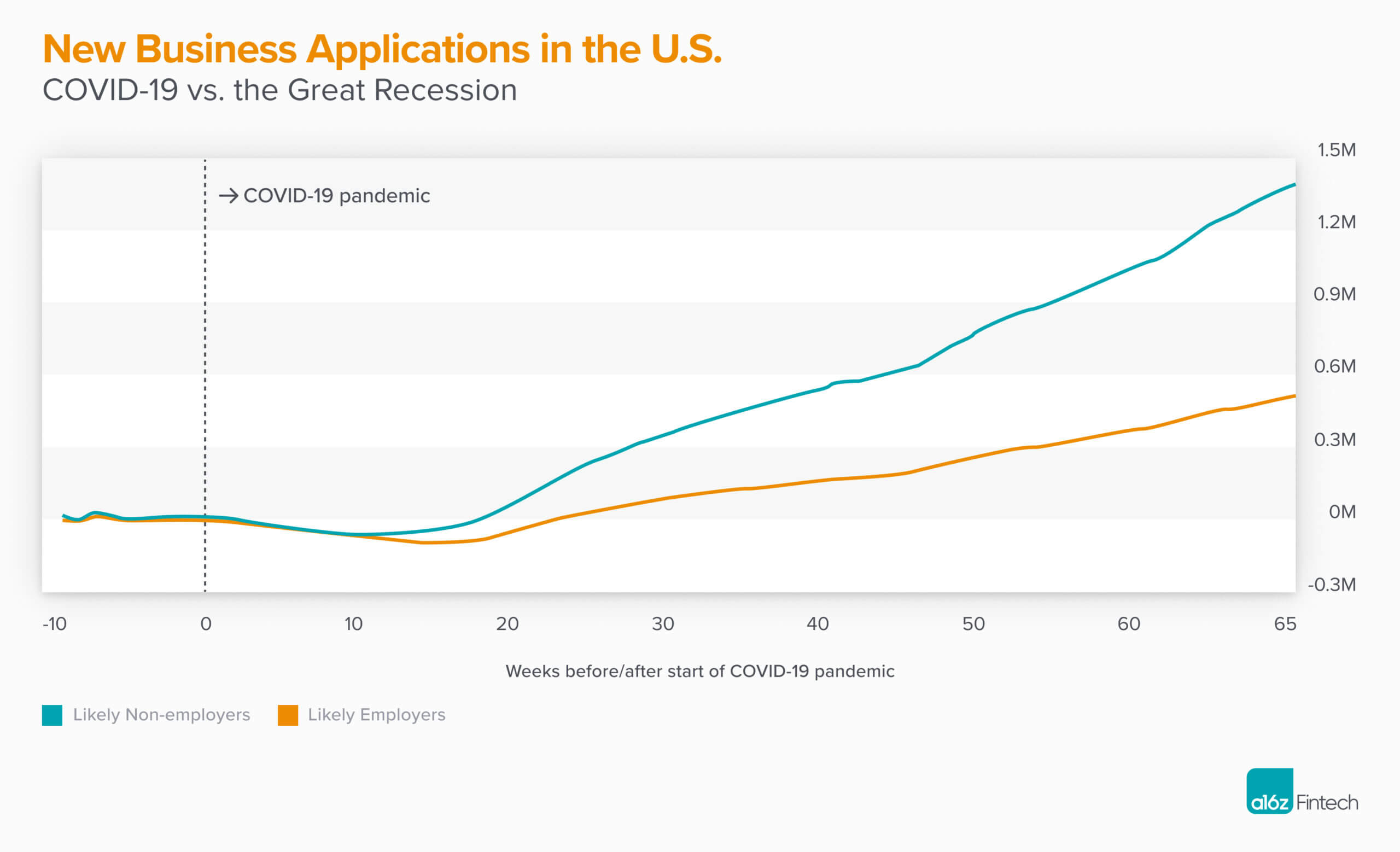

Lost in all this talk of digital nomads and side gigs, however, are the masses of independent professionals who are working on their own and making a living, but not necessarily pursuing their creative passions. Not everyone’s talents lay in the creator class. A lawyer, a recruiter, or even a venture capitalist may not recognize themselves in this new creator economy, but since the onset of the pandemic they are “going solo” — performing the work of existing professions without the infrastructure of a firm — at an astounding clip.

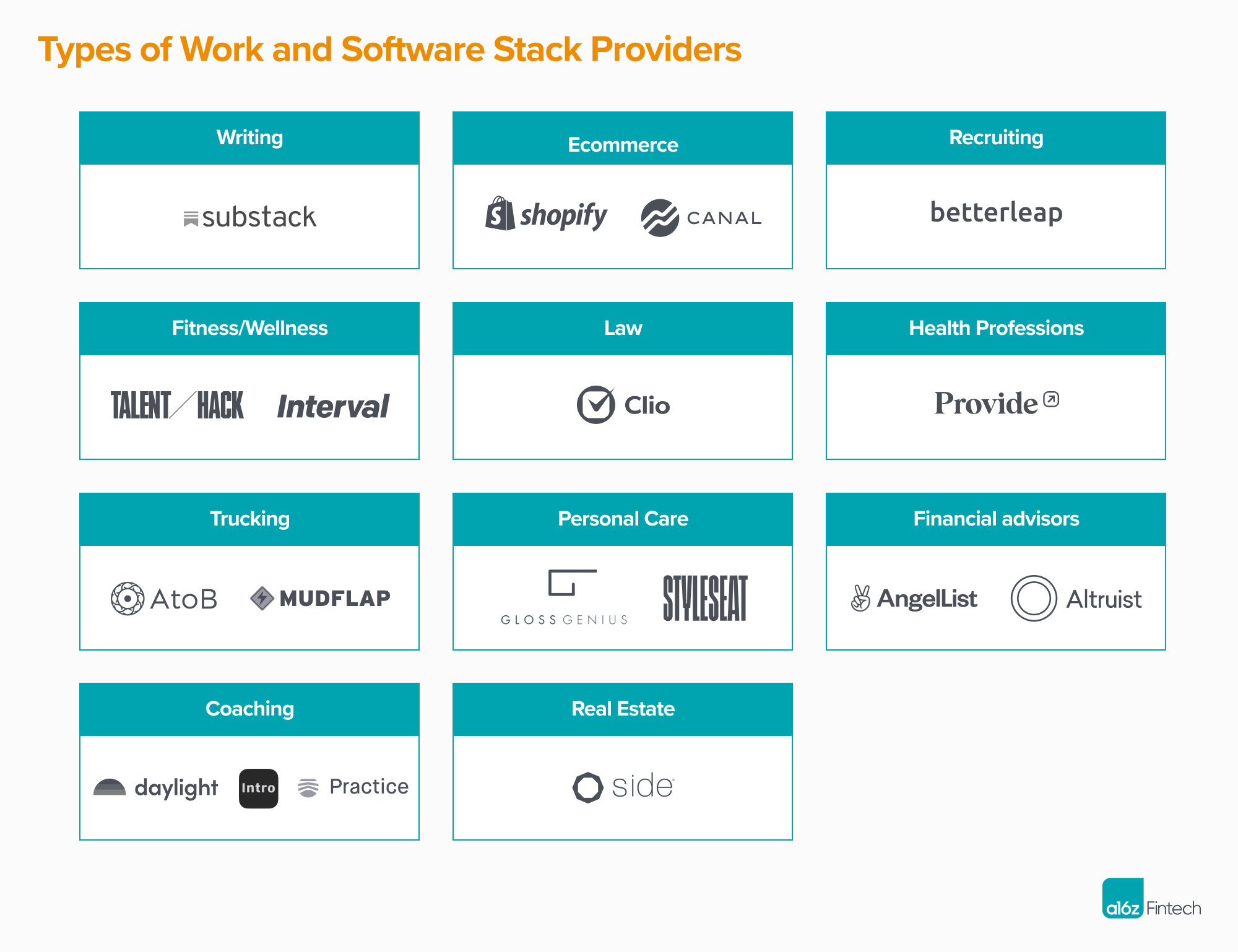

There’s a pressing need — and an opportunity — to build vertical-specific tools for workers striking out on their own. Much has been written about the proliferation of vertical software tools that help firms run their businesses, but the next generation of great companies will provide integrated, vertical software for individuals going solo.

Replacing the firm

Solo workers include two types of individuals: veterans, experienced professionals who are leaving their companies to set up shop for themselves; and rookies, career changers or young professionals who are entering a field for the first time, but without the backing (and restrictions) of a traditional institution. In both categories, these workers may have previously been daunted by the barriers, risks, and costs of going independent. They need the tools to launch, sell, manage, and market their craft so they can focus on doing the job that matters. A psychiatrist, an insurance agent, a decorator, an emerging hedge fund manager, a tutor — each requires a different set of tools to run their business.

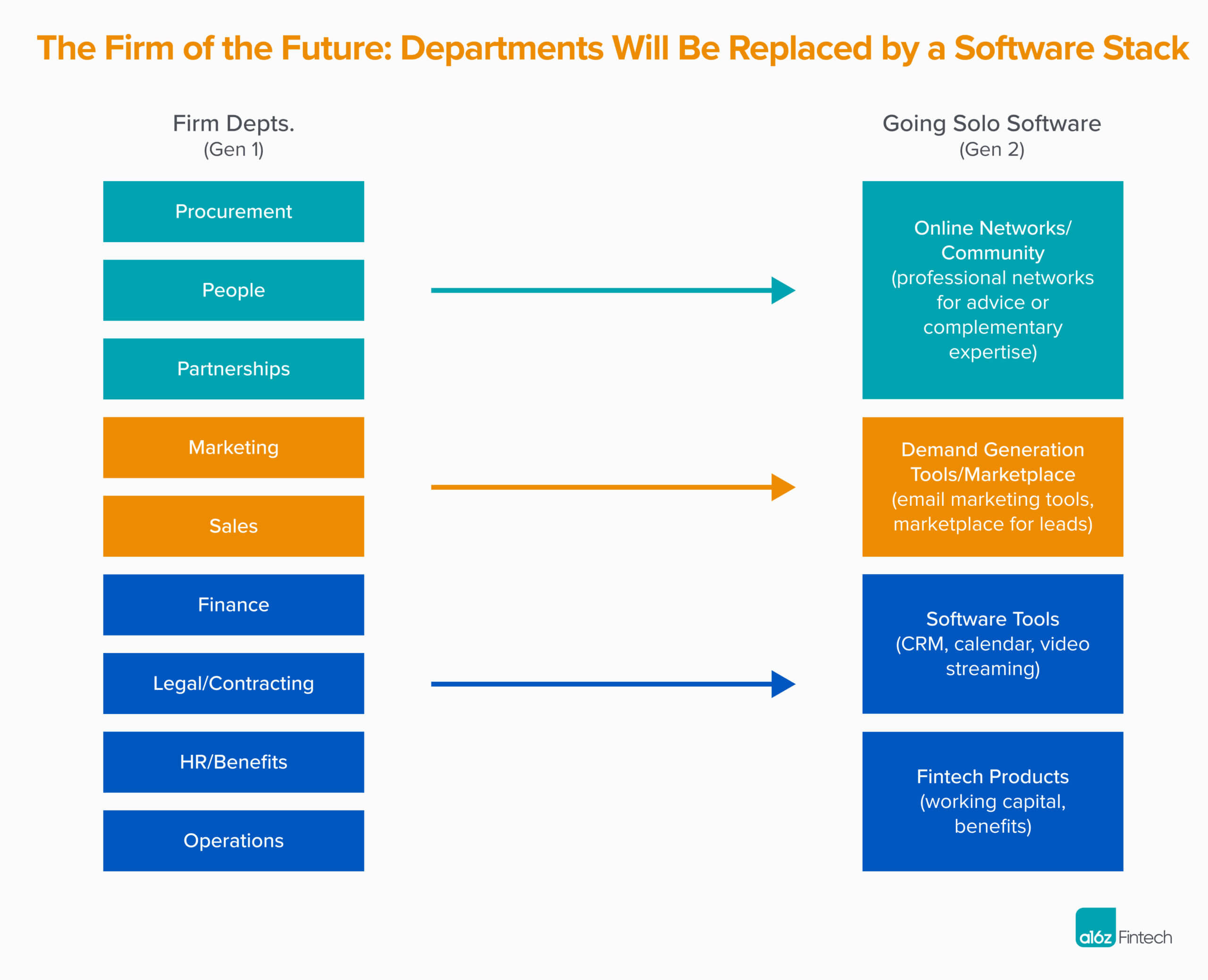

Solo workers venturing out on their own need to feel like they can replace the support of a company model. Traditionally, the firm brings three things to support the core craft or product:

- Operational support: functions like finance, legal, and HR that help people do their jobs

- Demand: generating customers (through marketing/sales, branding, and relationships)

- Networks: access to communities that support the individual

The solo stacks of the future will offer a mix of these three things (depending on what makes sense for any industry), giving workers the tools — and thus, the confidence — to leave their jobs. The software will be vertical-specific, as well, as lawyers, personal trainers, money managers, and graphic designers all need different tools, have different customers to market to, and require access to different networks to do their jobs.

One example of the solo stack is Shopify. This company provides ecommerce sellers with tools (websites, payments, etc.) and networks (drop shippers, suppliers, etc.) so that they can focus on producing, curating, or procuring the goods they sell. The seller needs the set of tools that the firm previously provided, but tailored to the individual level. This loosely breaks down into: a set of SaaS tools to manage the business (including the fintech tools to take payments and grow the business); marketing and lead-generation tools to move the business forward; and a set of networks to help these new solopreneurs be successful. Every category of work will have its own specific mix of these functions.

Building the software stack

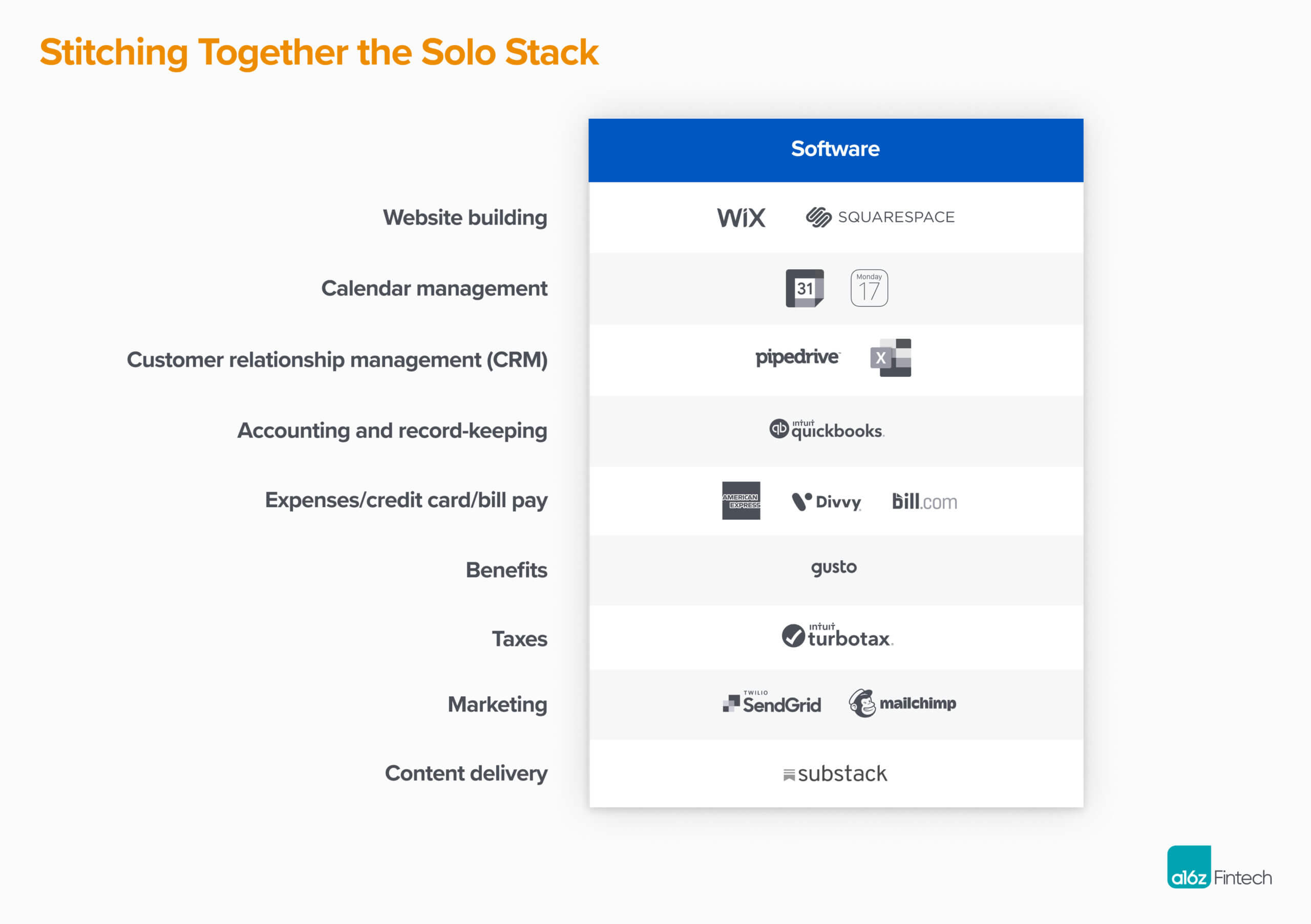

For most people going solo, the infrastructure to get started is not well known. In addition, managing accounting and bookkeeping, launching email campaigns, renting office space, and more takes a significant amount of time. This was historically the overhead that the firm provided internally or externally through accountants, office managers, and operations departments. Just figuring out what tax status to elect — an LLC or an S corp or a C corp or no corp — is not clear. By going solo, the individual ends up assembling a stack of one-off tools something like the list below, most of which do not talk to each other.

Moreover, a number of these tools lack functionality specific to the profession. Thus, the tech tools would be different: teachers need video and whiteboard functionality, whereas fitness instructors need to be able to sync music. The same is true for how to package, price, and bill products, the contracts and legal forms they need to set the business up and sign up customers, and so on. Solo workers also need software to connect them with operational needs. Finding office space for a freelance designer, a studio for a fitness creator, or a chair for a hair stylist are all different.

Imagine if vertical-specific and horizontal tools could all be bundled together and provide one “business in a box.” The stack would work together too: The calendar would sync with the customer relationship management software and the booking tool, cutting the time needed to create manual entries across software platforms. No-shows could automatically be billed the cancellation price. Expenses could automatically be routed and billed to the relevant client.

The software stack creates a “system of record” upon which everything else relies. If the software is the central hub where businesses track their customers, manage communication, and see how much money they are making, it’s also a platform for additional services, such as analytics around marketing efforts or tax estimation. Moreover, those additional services can leverage the data that the platform captures. An integrated software stack also drives stickiness — if a worker’s business runs on the stack, replacing it is difficult.

Enter fintech: operational tools and financial products

Typically, a firm requires upfront capital to secure an office space, hire people, buy or rent equipment, and procure inventory, for example. To grow, it seeks working capital loans to meet cash flow needs or term or equipment loans for large capital expenditures. For its employees, the firm negotiates and offers benefits like health and dental insurance, as well as job-specific benefits like workers’ compensation insurance.

A solo worker also needs these financial products, but accessing and negotiating them is considerably more difficult. Whereas a firm might be able to qualify for a small business loan or working capital line, an individual would need to take a personal loan with a guarantee against their sole and family assets, even if the money would be used for their business. The bank or commercial insurance company may not be accustomed to underwriting a single individual.

Here, the platform can help. The platform has data pooled together to help underwrite and negotiate better rates for a class of people, especially if it is tailored to the needs of a specific profession. This ability to take a financial leap has historically held people back from going solo. For example, Substack Pro gives writers an advance payment to support them branching out on their own.

Similarly, dentists, doctors, or photographers might need to secure lending to buy equipment that directly generates revenue. These financial products could be coupled with software that guides an individual through that initial journey.

When it comes to benefits, a fitness instructor has different workers’ compensation needs than a designer who sits at a desk all day. Solo truckers can’t negotiate for fuel card discounts, but a software platform that aggregates demand could do so. There are also financial products that could be unique to solo workers, such as income-smoothing products for contract-based payment.

Demand: Generating leads

Another critical feature of a firm is its ability to generate leads and clients. Within a firm, this can come from a brand, existing relationships, or a sales/marketing department. Customer acquisition is often the most difficult part of going solo. .

The relative importance of generating leads depends on 1) whether the platform is designed for veterans or rookies and 2) how monogamous the customer relationship is in that category.

An individual who has a strong set of clients — say, from a previous job — is less reliant on demand generation than an individual who is just starting out. An established recruiter with a strong reputation and a close network of hiring managers, for instance, may not need as much help generating demand as much as a young person trying to break into the recruiting space for the first time. The veteran is more focused on increasing retention and deepening relationships than on generating demand.

Categories with highly loyal or repetitive customer relationships also require less demand-side help. For example, when a customer has just one hair stylist or dog walker or cleaner, then both the customer and the provider need less help finding each other. On the other hand, for something like food delivery (e.g., Shef) and restaurant booking (e.g. OpenTable) where customers are often using multiple platforms and frequently looking to discover something new, lead generation is much more important.

Marketplaces that connect buyers with their customers are a classic example of lead generation. Freelance marketplaces like Upwork or Fiverr, for example, connect solo workers with one-off jobs. However, the marketplace model has its drawbacks. Solopreneurs often need to compete to retain customers, and some platforms make it difficult to maintain direct relationships with their clients. For this reason, there is always an opportunity to build a “vertical SaaS” competitor to a marketplace, especially in categories where generating leads is less critical.

The inverse of this is also true: a platform that relies on its ability to generate leads faces the threat of disintermediation. Once a provider (be it a hair stylist or a Pilates instructor) finds enough clients, the provider may elect to leave the platform. In that sense, the pure marketplace runs the same risks as traditional firms.

This is why building category-specific products is critically important.

Where providers are wary of competing with other providers, platforms will need to allow for a direct relationship with clients and other customer retention tools. Where disintermediation is a risk, platforms will need to provide enough software tools to drive stickiness. The platform may also need to build a business model that recognizes the dynamics of the particular profession it serves — that might mean charging a SaaS fee, rather than a take rate, for example.

Even on the most conservative side of the spectrum, these platforms can build a robust set of software tools for lead generation. For example, Shopify doesn’t have a marketplace, but it does invest heavily in tools and training to help generate compelling content, run email campaigns, and execute effective ad campaigns. This can help a solo entrepreneur find business while alleviating the concerns behind a marketplace.

Networks: Providing access to communities

Firms provide access to a set of complementary professional networks that would traditionally be inaccessible to an individual. A large retailer might have relationships with suppliers or shippers that the mom-and-pop store or a random ecommerce seller may not have. A newspaper has a network of editors to refine writers’ work or lawyers to fight a bogus defamation suit. Platforms for solo workers can provide access to those ecosystems, as well, without the clunky overhead of a firm. A good example is Substack’s legal defense fund, which can give individuals the courage and resources to go solo.

Firms also provide a social layer for individuals to collaborate and learn. Mentors have a stake in helping a new generation find their footing and training a new generation. Junior attorneys and accountants are often trained by senior partners. Individuals may turn to specialists within the firm if their clients have a specific issue around tax or another jurisdiction.

Colleagues also provide an outlet for sharing the highs and lows of a job. Bringing the offline community online can be challenging, especially when there is no shared coffee machine. However, platforms like Betterleap and Practice are working to create a sense of community among solopreneurs.

Making the numbers work

A natural question is which professional categories present opportunities. A very narrow industry may limit the total addressable market, but something like fitness can be broadened to include any sort of video-based wellness coaching course around diet and nutrition or meditation. Vertical software has started to pop up in a number of categories, but most are relatively unexplored.

The attractiveness of a category is measured not only by its size but also by the acquisition dynamics, specialization, and monetization opportunities. The more specialized access that the platform can provide to software tools, lead generation, and networks, the more valuable the platform can be.

Most of these businesses will likely monetize via some combination of:

- A fee for SaaS tools

- A take rate on payments

- Additional fees for other fintech products

- A take rate on lead generation

- Subscription access to a network

The mix, and the starting point for a software stack, is dependent on the core value the business provides. If the platform is generating leads and therefore revenue, charging a take rate on transactions is logical. If the platform is providing SaaS back-office tools, then a SaaS model makes sense. Most of these businesses will also monetize through payment processing.

Fintech offerings also help build a bigger business than a “niche” vertical may indicate by adding incremental revenue streams on top of the SaaS plus payments revenue. Fintech helps scale vertical SaaS in general, but that’s particularly true at the smaller end of the SMB market, when the SaaS fee is often even lower. To get things off the ground, the platform will likely start by providing some core service and then layering on additional products, likely via partnership. This decision to build vs. partner will also dictate the economics.

From a platform’s perspective, the other question is the customer acquisition model and the sales model required to build a “solo” platform. Since solopreneurs can function like a consumer, an enterprise business, or somewhere in between, threading a hybrid B2B/B2C acquisition model can be delicate. This balance requires the branding and marketing expertise of consumer business, as well as the sales and account management of an SMB-oriented business. Not only does the team need expertise in both disciplines, but the unit economics must also be able to sustain this hybrid marketing approach.

* * *

We’re still in the early days of individuals leaving their firms as they seek additional freedom, flexibility, and ownership over their work. We’re also in the initial stages of the software platforms that can identify and provide the core, company-provided services these workers previously relied upon. By enabling individuals to make the leap from the security of a firm to independent work, software will drive the continued growth of this market.

-

Seema Amble is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on investments in B2B software and fintech.

-

D'Arcy Coolican D'Arcy Coolican is a partner on the investment team where he focuses on marketplaces, social networks, and consumer technology companies.

-

Alex Rampell is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where he leads the firm’s $1 billion Apps practice.

- Follow

- X