B2C2B — also known as bottom up — has helped companies like Slack, Zoom, Dropbox, and other software companies break into B2B. Now B2C2B is coming to digital health, as a wave of startups are first selling products and services directly to consumers, and then when they reach a critical mass moving into insurance companies, employers, and other organizations.

But executing these two go-to-markets in parallel adds complexity. In this video, our team talks to six leading digital health builders — from Maven, Benchling, Buoy Health, Marley Medical, Bold, and Butterfly — for their takes on eight of the most important questions B2C2B digital health startups have to answer.

- How do you acquire users? [9:02]

- How do you build an engaging consumer product? [12:37]

- How do you price for consumer? [15:27]

- When do you go B2B? [18:54]

- How do you find your B2B buyer and product-market fit in the enterprise? [20:43]

- How do you sell B2B? [22:41]

- How do you balance two GTMs at scale? [25:33]

- What’s the role of professional services? [27:40]

For more on building digital health companies: a16z.com/digital-health-builders

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Transcript

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Julie: Hi everyone, I’m Julie.

Jay: And I’m Jay.

Julie: We’re really excited to be here kicking off the series about go-to-market in digital health. One of the biggest dimensions of evolution in digital health, arguably, over the last few years has been how companies are actually coming to market, how new products and services are being distributed to end users, and how these products and services are getting monetized.

As a founder who started a company over 10 years ago at this point, the sheer number and level of sophistication with which digital health companies are coming to market is just completely mind blowing.

Some of the examples that we’re going to cover in later playbooks include: selling to SMBs, two-sided networks, risk-based contracting with payors, and the emergence of new channel distribution platforms. But in this current session we’re going to cover this concept of B2C2B, or what you might call the bottom up, top down sales motion.

What is B2C2B?

Julie: This is the healthcare version of a trend that we’ve seen play out in B2B software. You might think about Slack or Zoom or Dropbox, or these products that you as an individual user can obviously adopt.

But what these companies are then doing is saying, now there’s a critical mass of these users and they might all work for the same company. Let’s actually parlay that bottom up motion into an enterprise sale to that company, and also potentially introduce more advanced features that are more enterprise grade. And that’s really the motion that we’re seeing play out in healthcare.

I’ll pass it off to Jay. Jay, can you walk us through why we’re seeing this now in healthcare when we didn’t really see a lot of this kind of activity in the past?

Why are we seeing B2C2B now?

Jay: We’re seeing digital health companies sell directly to the end user before going to the enterprise buyer with increasing frequency. And there’s probably a number of reasons that are driving that trend, but there’s at least four that I think we should call out — two on the consumer side and two on the enterprise side.

On the consumer side, there is an increasingly tech forward consumer and end user driving health care purchasing. We all are delighted by our technology enabled experiences in other parts of our lives. We get to call a car, order food, purchase clothes, pay a friend all with a tap and a swipe on our phone. And so we expect intuitive virtual first experiences in our healthcare system, especially after the work from home life we’ve adopted in 2020 and 2021.

These same consumers have far more discretion over and are steering a lot more of the healthcare spend themselves. There is a recent report estimating nationwide out-of-pocket spending on healthcare (i.e., not reimbursed by insurance) is set to hit almost $500B in the U.S. in 2021 and projected to grow to about $800B by 2026.

And then on the enterprise side, we frequently hear from many senior enterprise buyers (chief information officers, chief human resource officers, and other executives) about the record number of vendors pitching them new digital health solutions. This vendor fatigue is leading to a bottleneck. As a result, there are many promising B2B digital health solutions out there that don’t make it through the purchasing funnel.

And that third trend seemingly coincides with a fourth, which is a rising bar for validation. Enterprise buyers in healthcare and life sciences increasingly expect evidence that the solution works before buying.

For digital health startups, this creates a chicken and egg problem: how do you prove ROI without people using your product? B2C2B makes it possible to go to the enterprise and say, “Hey, a hundred or a thousand of your employees, your members, your constituents are already using this offering and are getting value out of it.”

The 8 Questions we asked founders

Jay: We’ve seen B2C2B work across a number of areas, including care navigation, women’s health, behavioral health, and many more. In fact, there are a lot of different flavors of B2C2B, and when we talk about consumers and end users, we could be talking about patients, employees, clinicians, or medical researchers. When we talk about businesses, we could be talking about employers, providers, payors, or life sciences organizations.

And while we as investors see B2C2B as a significant trend, we are fortunate in our jobs to meet and work with some of the best digital health companies today. So we interviewed founders and builders from some of those companies to ask the toughest questions that come up for B2C2B digital health companies:

How do you acquire consumers? How do you build a product that keeps them engaged? How do you price the consumer product? When is it time to go B2B? How do you find your business buyer and PMF with the enterprise? How do you actually sell to the enterprise? How do you balance two motions, one to the consumer and one to the business, at scale? What’s the role of professional services? But we started our interviews with the most basic question. Given the complexity of B2C2B, why are founders going this way instead of sticking to a more traditional and tried-and-true commercial motion?

Why choose B2C2B?

Jay: While B2C2B can be more complex to execute, it gives startups the power to acquire and engage users directly without first contracting with the payor, as we heard from serial digital health entrepreneur Chris Hogg, whose most recent startup Marley Medical is developing a virtual first clinic for patients with poorly managed disease. In Marley’s case, the consumers are people diagnosed with chronic diseases, and the businesses are the payors that pay for the healthcare services that those folks receive.

Chris: I think in order to understand B2C2B, we need to understand the B2B2C motion and why this has taken over. The reason is there were really no other options. If you’re not in the normal classification system, you have to go direct to the payer, who is either the payor or an employer, and contract directly on the product side of the house for a new product.

Now with virtual care, we are a normal product. It is a normal clinical service. In the eyes of a payor, they know how to pay for these types of services. And so we can invert the model and focus on our growth, focus on patient acquisition in a direct to consumer motion. There’s many ways that you could do that online through referrals or whatever, but control the ability to bring patients in, and then still get paid by payors because now we’re a traditional service. That could look as an in network provider, if you can figure out a code stack that works for you and covers the services. It could be in capitated arrangements, but you’re getting paid on these patients who you’re acquiring directly.

In a nutshell, the B2C2B motion is trying to control the growth through direct patient acquisition. I can build up my own funnels and channels to acquire patients, but then still get paid by the traditional system of payors and employers.

Jay: The power of direct acquisition carries with it a number of benefits. When digital health companies get to engage with their end consumer earlier, the result is often better products and better healthcare.

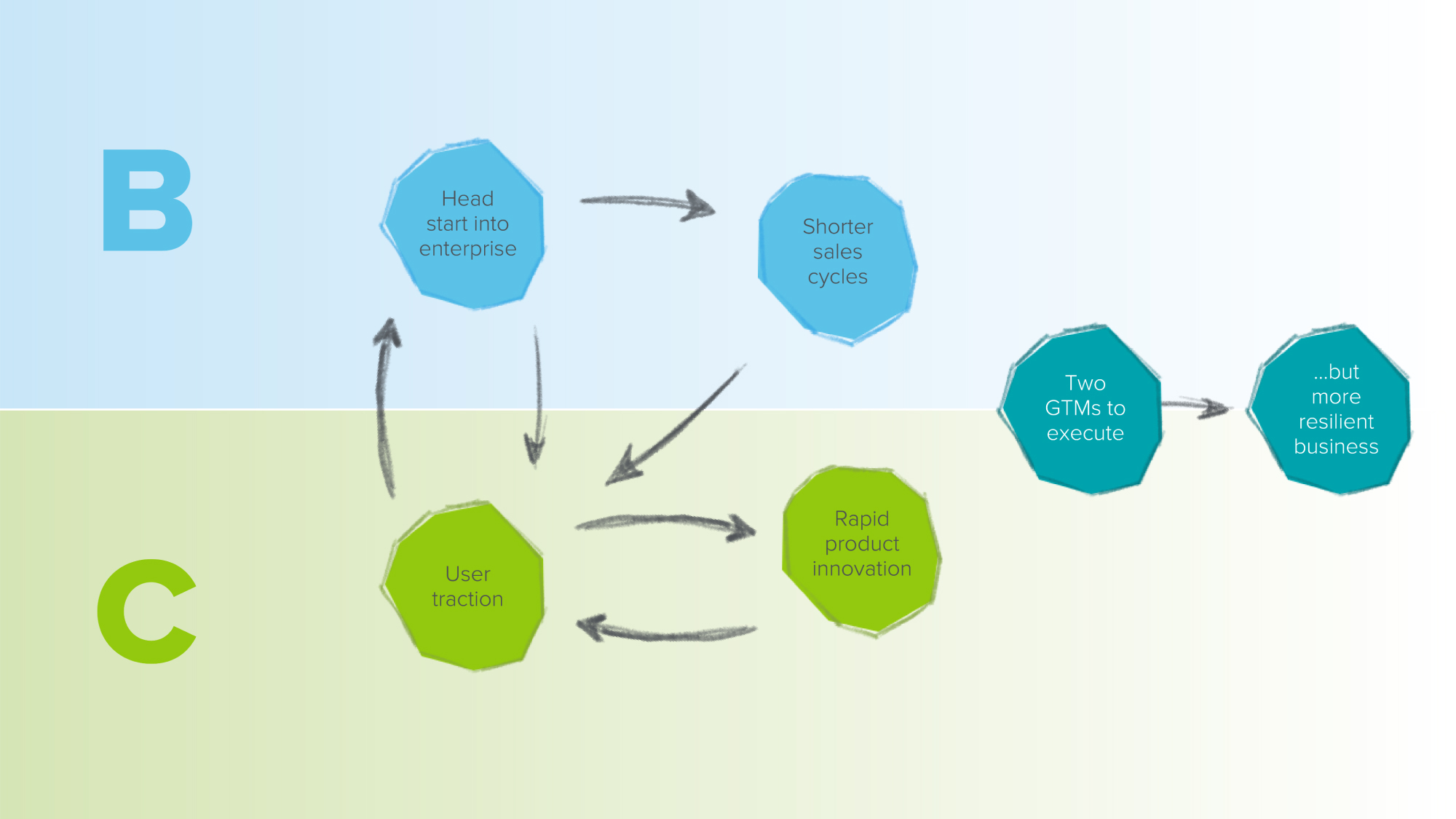

Companies reach product-market fit faster because they’re able to iterate and improve the product to keep acquiring users. Get enough of those users, and you can use that as a wedge to sell into businesses. Entering the enterprise with momentum and utilization data can help you shortcut an otherwise long enterprise sales cycle.

Now the biggest challenge we hear about with B2C2B is that you’re signing yourself up to execute two GTM motions in parallel, with the limited resources of a startup. The upside, though, is that if you achieve high engagement and stickiness in both motions, you’re unlocking a more resilient business model with greater long-term defensibility.

To this end, we heard from Kate, the founder of Maven, a women’s and family health platform and marketplace, that B2C2B can also make it easier to show earlier indications that things are working.

Kate: Because investors didn’t really know as much about digital health, you just when you raise money have to show momentum. And so we had to show some kind of momentum at every single fundraise and we needed a certain amount of capital in the early days to build out our product to be operational in all 50 states so that we could sell it into the enterprise.

We also just needed to show a certain amount of consumer momentum because our story to the investors was, “Hey, we’ve launched this new virtual clinic for women’s and family health. Consumers love it, and now we’re taking it into the enterprise.” That was a much better story and showed traction than just, “Hey, we have this thesis that this is an important category, and we have two small companies to pilot with. Will you fund us?”

1. How do you acquire users?

Jay: In the early stages, the goal is acquiring users. But how do you find & reach them? A lot of that comes down to what one founder called “consumer-channel fit.” Different businesses have different end consumers, and if you understand where your specific end users are looking for digital health information — whether it’s online on Facebook or offline in community gatherings, you can acquire them at a lower cost. For instance, Butterfly generated initial interest for its point of care ultrasound devices by targeting the most influential clinicians.

Bill: There are people that are deeply passionate about point of care ultrasound, and so we tapped into that. We looked at who was the most researched. We look at what centers they were in?

It was, it was, we very carefully targeting them. And then of course we were at the major trade shows back then, and I’ll never forget the first conference I went to at butterfly. You walk around the trade show floor and all the booths were empty. Ours would have a line in every direction.

Jay: And in another example of consumer-channel fit, Maven tried Facebook ads, but found they just didn’t do well at reaching their target demographic as other channels did.

Kate: There’s two things we did. First, giveaway marketing. Giveaway marketing, for those people who don’t know what it is, is when you partner up with a lot of other like-minded brands, you find a prize and you then blast your customer bases to sign up for the prize. Then you get email lists and off the email lists you try to convert people to use your product.

We did this very early on. It was one of the biggest marketing channels that we went out the door with in 2015. One of our early investors was an early investor in Noma, which is a wonderful restaurant in Copenhagen that everyone wanted to go to. Now that I’m seeing giveaway marketing and what people will sign up for, “it’s oh, here’s a hat.” And then, all these people sign up to win a hat. We offered an all expenses paid trip to Noma in Copenhagen. It was awesome. And then we went out to all these consumer brands. We launched it, and then we got something like 20,000 emails of women from like-minded brands that we could go market Maven to. It was a lot of work, and we had someone on our team doing this full time, but it was from a cost standpoint pretty cheap.

Then off the back of that, we would run and pick consumer campaigns to drive engagement in the product. One of our earliest consumer campaigns that was really successful was called therapist speed dating. We cut down our therapy appointments to 10 minute increments, and then we would offer free therapist speed dating to find a therapist for you to then book your therapy appointment. We would get the emails from these giveaways and then we would go drive this offer and campaign into our product that was just ours, and we started to get consumer volume off the back of some of this.

That was one motion. The other motion was, honestly, we just did field marketing.

2. How do you build an engaging consumer product?

Jay: Of course, acquiring users only works if they stay engaged, and that comes down to building a product that actually meets their needs, while also preparing for the complexities that come with scaling a digital health product.

Chris: The key challenge is to not build a product that you think people are going to need and use, but to really work backwards from the problem. I think one of the challenges that folks got into with B2B2C is that isn’t so acute. You’re able to build something that you can pitch well to buyers, but it might not be something that fits a problem that actual patients and users need to solve.

Especially with a direct to consumer acquisition approach, you have to try to break it down. What is a small unit that I could try to sell to this person or try to acquire them into? Because what you’re trying to do is prove there’s demand, prove that people want this product, or at least are willing to engage with it and then build it out over time.

Of course, the big challenge with healthcare versus a pure consumer product is that this is healthcare. This is health data. This is very meaningful stuff, and there is a minimum chassis that you need to do that. You can’t just throw out medical recommendations and see if they land.

The challenge is finding that balance of building something really small and atomic, but building it well, so that you’re a mini HIPAA compliant platform. Even if you’re just bringing people in online and HIPAA doesn’t apply to you, you’re already thinking about how you’re managing people’s data.

Jay: We heard something similar from Saji at Benchling, an informatics platform for life sciences researchers. They started by giving away the product to academic researchers and then staying close to their early users to iterate on the product.

Saji: You need to build for a very small group that you can then logically expand pretty easily. If we can get one academic lab being really successful in, let’s say, doing molecular biology research, why can’t we get a second? Why can we get a third? And so rather than trying to go broad, we were just very narrow and pointed, but the space we were in had a lot of room for expansion. That’s kind of how we thought about it.

If ten people or a hundred people were totally addicted to the software, that was a really good sign because what are the chances that we found just the exact hundred people who’d be completed addicted and then there’d been no one else after that? So I’d preach more focus in the early days for most of those companies.

3. How do you price for consumer?

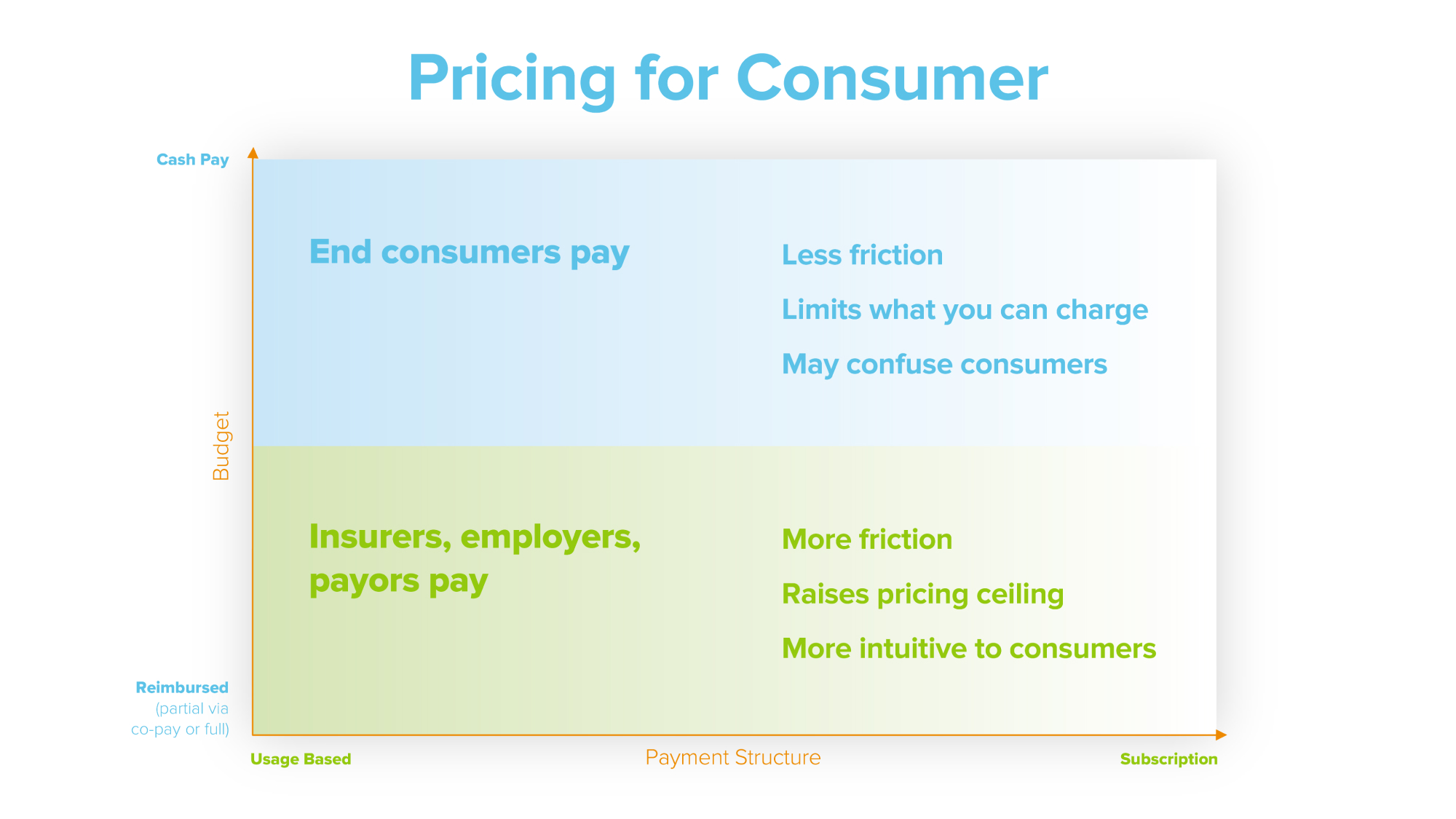

Jay: Another important topic in the early days of B2C2B is pricing. Almost no founder we spoke thought they perfected pricing. There are a variety of models, but you’re really balancing two trade-offs — the budgets you go after and the pricing structure you offer.

On budgets, you can simply do a cash pay model where you have end consumers pay, or you can allow for reimbursement where the insurer, the employer, and so forth covers part or all of it. Cash pay naturally has less friction for the buyer, but that also may limit you on how much you can charge overall. And you may run into confusion as different consumers have different expectations for who covers their digital health services.

Kate: Even though some of our early marketing was Maven is cheaper than the price of a copay. There was a lot of consumer confusion still around, “wait, shouldn’t my insurance pay for this?” When it became a more transactional, like I just need a prescription for something, then it was more straightforward because you were getting something physically. But when it was a service, it was harder to understand why your insurance wouldn’t pay for it, even if you hit people over the head with the logic of, but it’s cheaper than what your insurance even has.

Jay: If you choose a cash pay model for the end user, how do you set the right price? Here’s how Butterfly did it for their point of care ultrasound device.

Bill: The view, first of all, is it had to be very affordable. It had to be at a price point where clinicians would just put in their credit card and then also could be afforded by many parts of the world. Jonathan, our founder, really just decided $2,000 is the price and made everyone else figure out how to get there. And I think it was the gut feeling that $2,000 was that right price point that they could get the consumer, in this case the clinician, to put in their credit card.

Jay: The second tradeoff is around how you structure your pricing, whether you price for usage or in a bundled offer. If you do usage-based pricing, that might seem more fair: you pay for what you use. But you may discourage usage and, more importantly, the user feedback that is super informative to your early product development.

Alternatively, you can structure your pricing in a subscription, such as a monthly fee. That may allow for a more natural usage pattern — customers can use as much as they want for a fixed fee — but it does add more friction for the initial purchase.

Ultimately, in B2C, you are pricing for engagement more than revenue. But as we heard from Amanda at Bold, which develops fitness programs for seniors aging in place, what you do in B2C has implications for your B2B pricing.

Amanda: We were actually less fixated, candidly, on the B2C pricing strategy. It was what is the potential ROI story that we can tell on the B2B side, and then on B2C we really privileged engagement. We did pricing experiments, and that was great, but I would say, be mindful of whatever you put out as your B2C pricing, because you will have to explain the difference between B2C and B2C2B.

Jay: When it comes to B2B pricing, we heard from founders that most business buyers preferred simplicity, but that really it was a matter of aligning incentives with the business you were selling into. For instance, payors are used to a per member per month [PMPM] model, so that tends to be their preference, while most employers would rather have the simplicity of an annual license.

4. When do you go B2B?

Jay: But stepping back from pricing, the bigger question is when should you flip the switch and go B2B? We generally recommend turning on enterprise when you see repeatable usage patterns among a core customer group through concrete data gathering. Several digital health founders have told us that their enterprise buyers basically expected them to have run a randomized controlled trial demonstrating the ROI before signing a partnership.

Amanda: We launched our research study at the same time that we launched our DTC [direct-to-consumer] offering. The moment that we had our six month outcomes, and we looked at what the six month outcomes were as far as reduction in annualized fall rates and improvement in balance and strength and mobility, that was for me the moment that I felt really excited and confident to take that story and that offering to enterprise customers. We felt like we were sufficiently de-risked in the eyes of someone who would be excited to be innovative, but wants to know this isn’t a total sort of shot in the dark. The hard data from that research study also allowed us to think about what is the ROI and over what time period.

I think another way to do it — and I get this question a lot — is volume. Maybe you haven’t done a research study, but you have really big volume and you can start collecting that data and saying I already have this existing base of individuals. I think that’s another way to position and share impact when you’re having B2B conversations.

5. How do you find your B2B buyer and PMF?

Jay: Once you go B2B, you have a headstart from the B2C motion, but you still have to figure out how your end consumer connects to a business buyer. At Benchling, they followed their academic users into life science companies.

Saji: You had these brand new companies oftentimes being spun out of academic labs that used Benchling that were doing breathtaking things: gene editing medicine, lab-grown meats, you name it. Some of the scientists who used Benchling for free in schools started to go over there, and then we just followed them and followed the user.

Actually though, at first, we really struck out trying to sell anything to these companies. Scientists had used Benchling in school, and they liked it, but they weren’t going to buy it. The business value wasn’t there.

That’s when Benchling really started to grow. It went from a productivity suite for end users to building the single source of truth for the business, and the end user experience was what enabled us to get the data to then present back to the business, like here’s all your scientific data in one place, highly organized and structured.

Jay: For Benchling reaching an enterprise buyer meant evolving their product offering to meet the more complex needs of an enterprise organization. Similarly, Butterfly overcame the resistance of hospitals to allow clinicians to use a third-party device, even one those clinicians paid for themselves, by creating additional enterprise features.

Bill: We knew their concerns around security and governance and integration, and so we built a software package for that. That then created the right dynamic, where we actually had a product to sell, which had higher recurring SaaS dollars attached to it. It was a win-win from that perspective: we could solve the clinicians problem of wanting to use it in the hospital, and then we’re driving increased subscription revenue and deepening our tentacles in terms of the integration into the organization and spanning across the organization to do more.

6. How do you sell B2B?

Jay: So far, we’ve heard that the timing of when you go B2B comes down to having an ROI case and a sufficient volume of users. And then you have to find your enterprise buyer and layer in the additional product features they care about. But once you are in front of that buyer, how do you actually sell?

Bill: One of the things I deeply believe is that people and organizations buy with their heart and rationalize with their brain. That storytelling about what this device can enable using it at scale and how it’s integrated into care and to care pathways is why people are buying it. You then just simply need to justify the ROI on the backend as to why that makes sense for an organization. Health systems have thin margins. They can’t be investing in things that don’t have some sort of ROI, or at least a breakeven. You have to create your price, but the storytelling is much more important, and then the price just has to be justifiable at the end of the day.

Jay: Throughout the conversations with founders who have successfully gone B2C2B, we heard about the importance of never losing focus on the end user. Even when you are selling to enterprise, end user product engagement is your advantage. Here’s Andrew Le, founder of Buoy Health, explaining why even as a B2B company user engagement is the most important metric.

Andrew: The fact that people use something, anything is the most important metric of success for the buyer. Which leads me to that evolution back to the consumer. Why would someone want to use something? Because it’s super useful to them. That’s it.

When you think about selling to the employer space, our head of people wasn’t buying stuff for Buoy looking at a calculator and being like, “how much money did I save on email this week because I bought Slack?” They weren’t saying, “how many times did I not have to keep an Excel sheet updated, or get people to log on to Excel and how much time and effort that would take, but instead people logged into Namely. They’re not doing that kind of calculus. They’re just looking at how many people are using Namely or how many people are using Slack or how many people are using insert service, benefit, product, whatever it may be.

For us, the reason it circles back around to the consumer was like, “shoot, we should just care about being super, super useful to the consumer, to the end user.” That’s all that matters. And playing with the numbers or playing with different ways of measuring ROI is in and of itself a red herring.

7. How do you balance two GTMs at scale?

Jay: Once you’ve gone to the enterprise, a company is effectively executing two go to market motions at once. It can almost create this schizophrenic pressure. How do companies in the later stages balance the needs of the consumer with the needs of the enterprise? Like Andrew at Buoy, for Amanda at Bold, it’s about always coming back to the end user.

Amanda: There’s absolutely considerations. Are you integrating with Epic? Can you collect this additional information that we’re going to need to verify that they’re eligible through their health plan? Honestly, when we add those pieces in, I think about we establish the best practice and then we start to see how implementation can actually pull us away from what we believe our high bar standard should be. Then, we rally the team to say, okay, how do we tick off the needs that our enterprise customer requires? And we absolutely will do that, but then pull ourselves back up so that we aren’t allowing the default to be this perhaps lower engagement, higher friction experience and incrementally improve.

That has been really helpful for our product team, as far as understanding there’s going to be some deviations, we have to keep experimenting. But we know what’s possible, so let’s get back to that maximally engaging experience.

Jay: While focus on the end user is important, you also have to manage enterprise expectations. Otherwise your product team can end up pulled in too many directions.

Bill: It’s the age old problem of going into the enterprise because you’re talking to a leader of a really important health system that could be your first reference account and they’re demanding some feature or capability, it’s easy to make the mistake of over promising. What I’ve learned on the commercial side is tell your product and engineering people to be conservative, start there. Whatever they give you to be conservative, add a quarter to it.

8. What’s the role of professional services?

Jay: Once you have sold into the enterprise and are now managing two go-to-market motions in parallel, professional services can play an integral role in making these more complex customers successful using your product.

Saji: Big organizations need help. They’re so large that they need extra support to make changes and who better to know how to implement your product than you. Those are your people who know your product, and they’re going to bring back that knowledge to your R&D teams and help make the product better.

Adding promotional services was an incredibly important business decision for us. Now you need to make sure that you’re not using professional services as a band-aid to cover for bad product or to avoid building product in certain areas, or to have to customize the software. A big part of the thesis behind Benchling was that we could build something that was highly configurable, so it could be applied to different scientific use cases, but didn’t require a bunch of programming for our different customers, who are stuck in some customization hell, so we heavily employ services. We sell services with every deal we do. It doesn’t matter if you’re a tiny startup, and it’s a very fixed quickstart package kind of thing, a couple of hours. If you’re a giant enterprise moving everyone to Benchling, we may be doing services with you for 18 months across 2000 people in 20 sites. The customers, the enterprise ones especially, want to know not only are they buying the software, but services are a guarantee that they’re gonna be successful with the software.

Jay: Okay, so we’ve heard from founders about the journey from the early days of engaging your first users to balancing two motions at scale. And perhaps most exciting in all of this is that B2C2B keeps those who build digital health products close to the end users who need them.

At a16z, we are incredibly excited about the potential of this approach to improve healthcare and lower costs. I’ll pass it back now to Julie to share our perspective on what our team pays most attention to as investors.

Investor perspective: what we look for in potential investments

Julie: So we wanted to just share a few things about what we would look for in evaluating investment opportunities. There’s really three major pillars to that. One would be focused on the C part of the motion. Really at the earliest stages, we’re looking for B2C traction, and it largely looks the way that you would evaluate any B2C business. You’ll look at the cohorts. You look at adoption, retention, stickiness. You look at marketing efficiency — your CAC [customer acquisition costs] versus your projected LTV [lifetime value].

This is really where compared to a B2B2C motion or even just a straight B2B motion, you would really expect to see far more user data and validation earlier in the trajectory of that business than you would otherwise.

The other thing to point out on the C side is really product velocity. One of the benefits, as we mentioned earlier, of doing the B2C motion to begin with is the ability to have much higher speed of iteration on your actual product. That is certainly something that we would qualitatively look at as well. So, that’s pillar one.

Pillar two would really be around the B. When you’re looking at a seed or even a series A stage company, there might be less quantitative data to look at on this front. Here we’ll look for just the early validation. How many cycles have you spent on the enterprise side? Do you actually have a pipeline of enterprise logos and an ability to really tell that enterprise story in a reasonably compelling and articulate way? Certainly bonus points if you actually have a contract with an enterprise buyer and have actually gone live with an enterprise.

And then the final pillar that we generally look for is: does your financing plan and your actual company build plan appropriately accommodate the fact that you will be investing in essentially two motions in parallel? As we mentioned before, B2C2B sounds great, but it actually is quite a bit of work to build a consumer muscle at the same time as building that enterprise muscle. And so we just want to make sure that founders fully appreciate that.

So in closing, thank you for joining us for this first in a series of digital health go to market playbooks. If you happen to be a digital health builder who is thinking about, or actually executing on, any of these go to market strategies, we would love to hear from you, so please do reach out with your feedback and comments.

Benchling, Bold, and Marley Medical are a16z portfolio companies.