In the wake of the GameStop short squeeze, payment for order flow—the practice of market makers paying brokers to execute customer orders—has fueled no small amount of debate: Is it a tactic deployed by large capital markets institutions to steal money from the less informed, or is it an enabler of low cost, highly efficient stock trading for all?

Much of the recent scrutiny is based on a misunderstanding of the underlying market and the complexity of the forces driving it. How does an order given to a broker like Robinhood or Schwab or ETrade become a trade? And if trading is now free, does this mean that you—the investor—are not the customer, but the product being sold? The answer (a definitive no) requires a closer look into the structure of markets and market making.

Making a market

If you want to sell 273 shares of, say, Facebook stock, what are the chances that at that *very* second, somebody else wants to buy precisely 273 shares of Facebook stock? Probably zero—queue the market makers. A market maker doesn’t bet on the direction of the market; rather, a market maker is really a risk transfer agent – someone who helps transfer risk between buyers/sellers in the market by bridging the gap in time between when you want to sell your shares and when someone else wants to buy those shares, or vice versa.

A market maker bridges this gap by warehousing (holding) the risk – the position it just bought from you – on its balance sheet by using its own capital. As compensation for taking this risk, the market maker earns a very small spread, often less than a penny per share.

A market maker bridges this gap by warehousing (holding) the risk – the position it just bought from you – on its balance sheet by using its own capital. As compensation for taking this risk, the market maker earns a very small spread, often less than a penny per share.

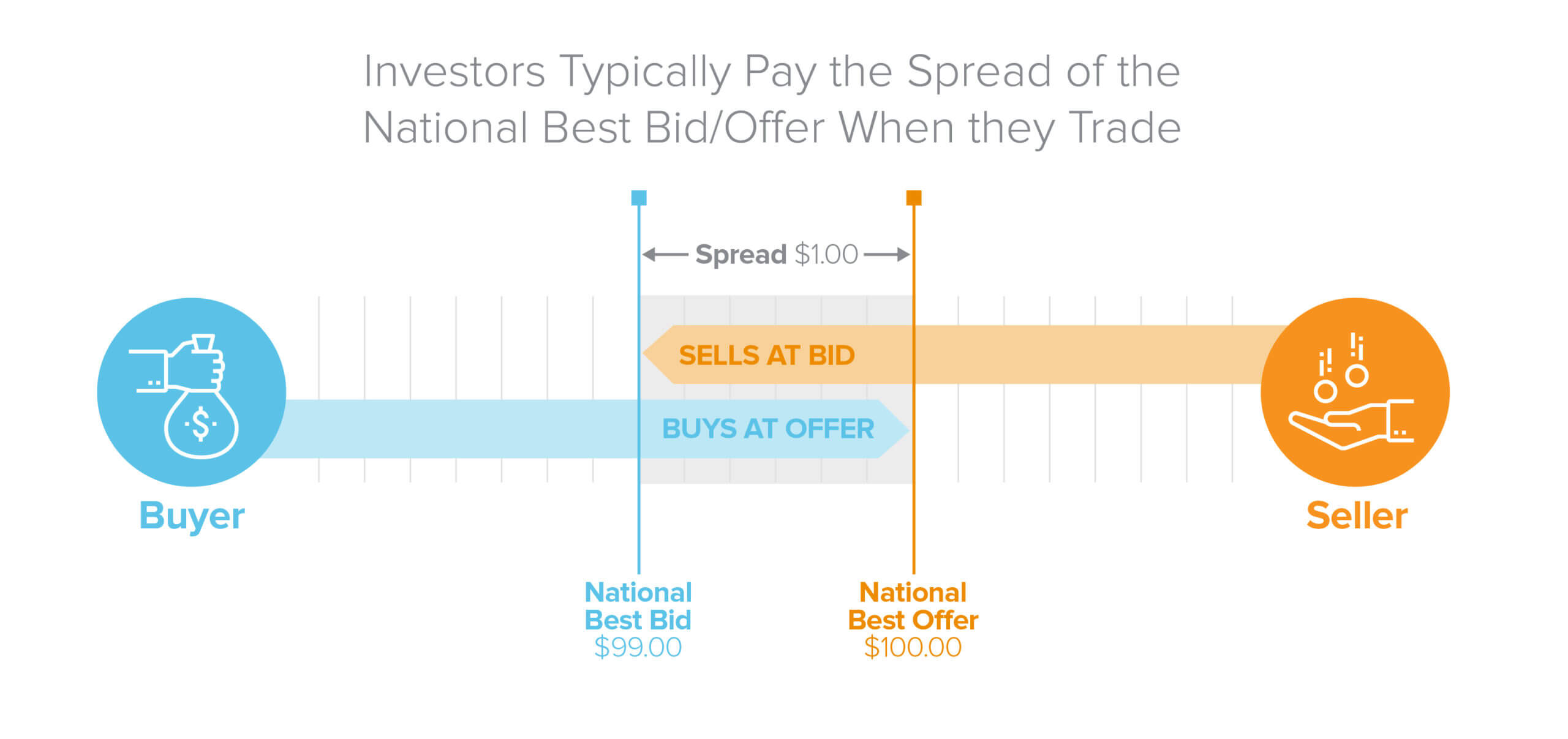

The spread, that is the difference between the bid price and the offer price in the market, is the implicit cost of being able to immediately trade (buy or sell) in the market. The bids and offers that market makers provide are often called liquidity. The more liquidity, typically, the narrower the bid-ask spread and the cheaper the implicit transaction costs. Without this liquidity in the market, buyers/sellers would have to wait around until they found someone willing to sell/buy exactly what they were buying/selling.

The iBuyer Opendoor, for example, is a market maker for homes: before Opendoor, a house would sit on the market for months waiting for a willing buyer at a particular price. Opendoor bridges the time divide, gives cash to the seller, warehouses the home, and resells it when demand surfaces. Why? To profit—taking on risk, of course—but when done right, this is clearly a win-win-win for the seller, for Opendoor, and even for the buyer.

Market makers perform the same function for stocks. Let’s go back to the hypothetical 273 shares of Facebook referenced above. A market maker will buy your 273 shares instantly, hoping to find a buyer in the immediate future. Your sell order is filled immediately at a price that is at – but often better than – the best available price anywhere else in the market. There is a common misconception that market makers are front-running stock trades, effectively saying “here’s a market order I got for Facebook, I’ll buy a bunch for myself first, and then sell at an arbitrarily higher price.” Not only is this empirically false, it’s also illegal. If anything, market makers often are “backrunning”—they fill an order at a price better than the best market price, but then have to scramble to identify an actual buyer or seller later to manage their own risk.

So what am I missing here? How does the market maker make money if the consumer gets a better price?

As described above, the market maker’s business model depends on its ability to net buy and sell orders over time. Let’s pretend that about 15 minutes before you sold your 273 shares to a market maker, someone else bought 210 shares from a market maker. When the market maker bought your 273 shares, its short 210 shares position in Facebook became long 63 shares. Most of the shares you sold to the market maker simply reduced its position.

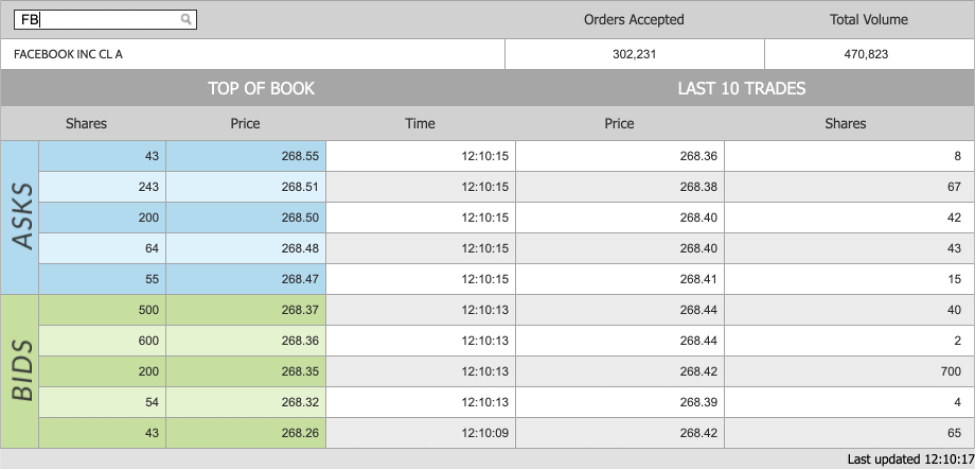

Why would a market maker do this? Well, just as with Opendoor and homes, market makers believe they will get compensated for the risk of filling the order. Market makers primarily seek to earn the bid-ask spread. Let’s say that a lot of people want to buy Facebook at $268.37, and a lot of people want to sell Facebook at $268.47. That’s what’s called a “spread” of 10 cents. A market maker would profit here by filling “market buy” orders at $268.47 (the best offer on the market), and filling “market sell” orders at $268.37 (the best bid on the market). As long as the market maker can roughly process the same number of buys as sells, there is a profit to be had. But don’t try this at home, folks—there is a substantial amount of risk that the trades are imbalanced (e.g., more sells than buys), and the price moves against the marker maker before it ever finds someone with an order to help reduce its position. “Making the spread” is effectively the market maker’s compensation for taking on the risk.

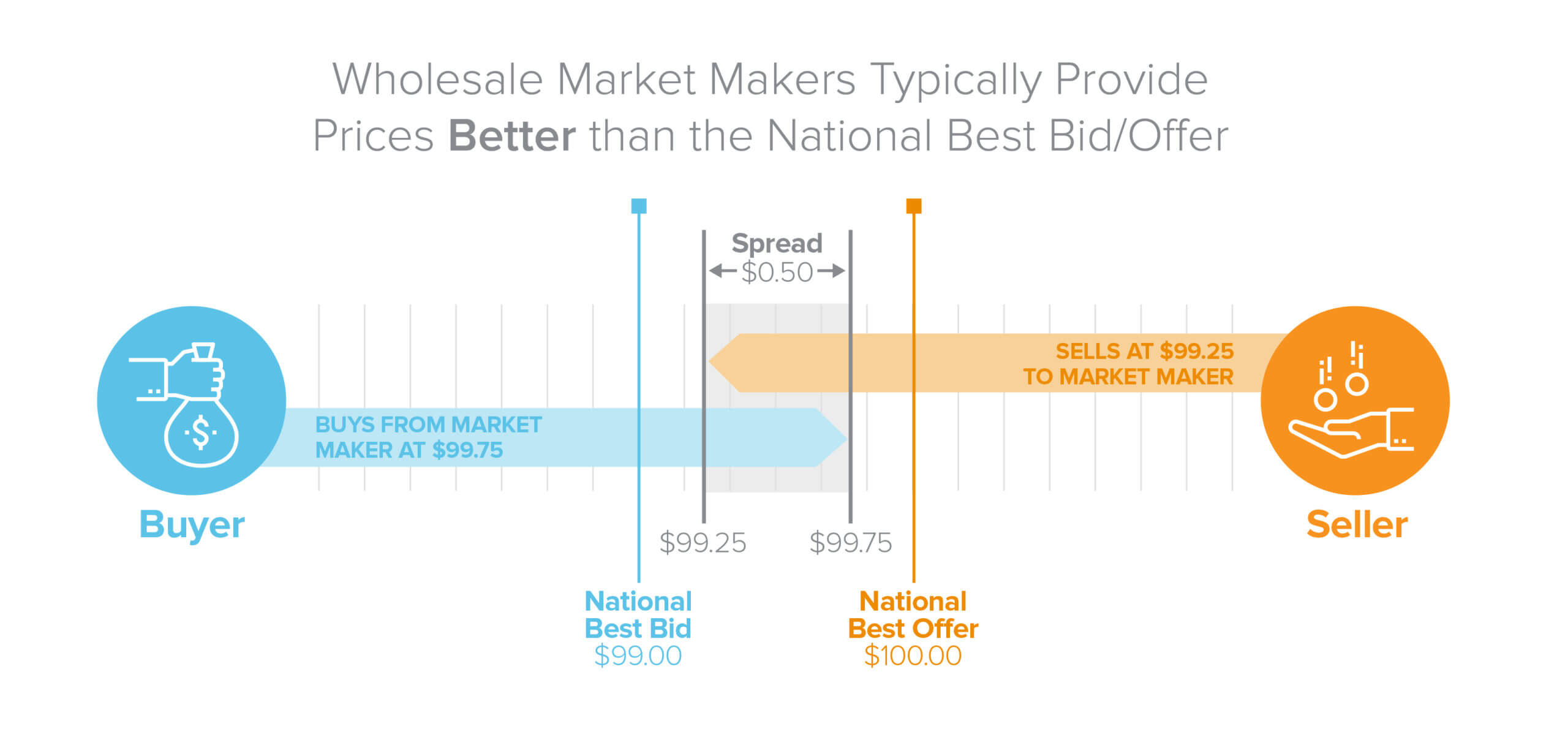

When things go according to plan, market makers receive more and more orders and can often trade “inside” the published bid-ask spread—actually improving the price you receive compared to the best quoted price on any exchange. Filling your market buy order for Facebook at $268.42 instead of routing to an exchange that would fill it at $268.47 would represent a five cent price improvement over the best offer, which the market maker can sometimes do by matching against an offsetting order now or against an offsetting order later.

For a very volatile security with a quote that moves all over the place, spreads can be VERY large. As long as the market maker is grabbing buys and sells equally, it should earn the spread, which represents a profit. But if the price “runs away” on one side of the trade—say, the market maker gets 300 shares of buying, then 1,000 shares of buying, then more and more and more buying, it then needs to “find” those shares later at a higher price, and is taking on increasing amounts of risk. Most market makers therefore have risk models around how imbalanced they allow their positions to be.

For a very volatile security with a quote that moves all over the place, spreads can be VERY large. As long as the market maker is grabbing buys and sells equally, it should earn the spread, which represents a profit. But if the price “runs away” on one side of the trade—say, the market maker gets 300 shares of buying, then 1,000 shares of buying, then more and more and more buying, it then needs to “find” those shares later at a higher price, and is taking on increasing amounts of risk. Most market makers therefore have risk models around how imbalanced they allow their positions to be.

Retail volume tends to be tautologically “small” relative to institutional volume—if any individual retail investor were buying, say, >1% of the shares in any given company, that wouldn’t be considered “retail.” Remember that the risk a market maker takes is if the price “runs away” with a flood of directional orders—ONLY buys, or only sells. Bids/asks on an exchange might be from giant institutional investors and market makers, whereas orders coming from retail investors are…from retail investors.

Retail volume tends to be tautologically “small” relative to institutional volume—if any individual retail investor were buying, say, >1% of the shares in any given company, that wouldn’t be considered “retail.” Remember that the risk a market maker takes is if the price “runs away” with a flood of directional orders—ONLY buys, or only sells. Bids/asks on an exchange might be from giant institutional investors and market makers, whereas orders coming from retail investors are…from retail investors.

Part of what makes market making difficult is the need for speed. You’ve probably heard of “high frequency trading” (HFT)—the use of computer programs to transact stock orders very quickly to take advantage of short-term market movements. To compete with HFT players, market makers have to make very quick decisions when they quote prices, and ensure they don’t become stale against market movements. Thus, not only do they take on the risk of potential imbalances of buy and sell orders, but they have to do so quickly to stay in the game.

Depending on the balance of buy/sell orders in a given stock or on a given day, it’s common for market makers to not make any profit after accounting for all of the costs they incur to manage their risks. Given the competitive and narrow profit per trade margins at which they operate, market makers can lose significant money if they do not update their bids and offers when the market moves. In other words, this stuff is very competitive and very hard.

The role of the exchanges: makers, takers, and fees

Most people have heard of the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq, but there are dozens of other venues in total that can “trade” stocks.

How does an exchange make money? There are many models, but let’s look at NYSE’s electronic exchange, ARCA. You can see a list of fees here, ARCA employs what’s known as a “maker-taker” model, paying money for orders that add liquidity (makes the price) and charging for orders that remove liquidity (takes the price). What does this mean?

The order book—representing liquidity—is a list of all of the bids (buy orders) and asks (sell orders). If you say “Hey, I’ll buy 2,000 shares at $268.11, even though it’s below the current market bid price so I know I might not get filled, but it’s a binding offer” you are *adding* liquidity to this market. If you say “Cool, I’ll sell 55 shares at the best offer ($268.47)” then you are *taking* liquidity.

When you take liquidity, you pay a fee. When you make liquidity, you get paid a rebate. The exchange profits because it charges more for “taking fees” than it pays for “making rebates”—say, $.0030 for taking, and $.0020 for making, meaning the exchange keeps $0.0010. A handful of exchanges like BATS BYX, CBOE EDGA, or Nasdaq BX invert this economic structure into a “taker-maker” model and charge a fee for “making” but pay a rebate for “taking.”

Retail is fundamentally different

In 2005, the SEC passed the Regulation National Market System, known as RegNMS, requiring brokers to obtain “best execution” for their clients within the NBBO, National Best Bid and Offer. But remember: there are dozens of exchanges, and the broker has an obligation to get the best bid (if executing a sell) or best offer (if executing a buy), also taking into account execution speed. Market makers, however, can give the retail order “price improvement” by executing it at a price that is better than published prices and warehousing the risk to offset it against existing or future retail orders. Schwab publishes exactly how much price improvement their customers get, as does Robinhood, and it is substantial. The vast majority of trades that retail brokers execute have better prices than are found on any market. Retail money isn’t dumb money at all; rather, it’s “balanced” money – a good mix of buy and sell orders, and small on a per-order basis compared to institutional flows—which increases the odds that a market maker will receive offsetting orders throughout the day, thus making it economical for a market maker to provide substantial price improvement.

Critics of retail market making argue that market makers are actually withholding liquidity from exchanges—but there is no data to support that this is the case. There are many, many venues where securities trade, and exchanges are not exactly profit-spurning entities. If there were a single monopoly exchange where *all* orders were processed, it might have more “immediate” liquidity, but at what price and at what rake? (Hint: monopolies charge a lot.)

Today, retail investors benefit from trading at better prices than are publicly available—to the tune of $3.6 billion in 2020. The fragmentation of trading venues combined with the cutthroat pricing pressure placed on market makers actually works to give consumers good pricing. It’s well understood (and many published studies, such as those by Prof. Robert Battalio at Notre Dame, agree) that the retail investor could be hurt significantly if all retail orders were forced to trade on exchanges and could no longer benefit from price improvement.

One way of thinking about this is similar to wholesale when buying normal products: when you buy a car at CarMax, CarMax buys cars in advance of demand—anticipating demand, but bears the risk of cars aging or going out of trend should they remain unsold. Consumers could potentially buy cars cheaper from the private sellers, but would have to search for sellers and wait longer. However, because of CarMax’s high-volume turnover, operational efficiency, and geographic network of distribution, it is able to provide buyers/sellers better prices than they would get at other dealerships PLUS valuable immediacy. All parties are better off.

So what is Payment For Order Flow?

The retail brokers aren’t stupid. They know that market makers are profiting on the spreads due to the balanced nature of the buy/sell orders from retail customers. Retail brokers could do the market making themselves (“internalizing” customer orders instead of sending them to market makers), or they could route every order straight to an exchange (sometimes earning maker fees directly, but also paying taker fees). So some retail brokers ask for a share of the market maker profits. Retail brokers typically route orders to a handful of market makers, allocating more to the market makers that provide the highest amount of price improvement to the retail investors.

Because of the highly competitive nature of market making, retail brokers benefit from having many robust market makers fighting to earn their order flow. In addition to better economics for retail investors, this competition among market makers provides a high degree of resiliency to the market; if Citadel kicked the bucket tomorrow, the retail broker would not be impacted much, since Citadel’s trades would just get reallocated between Virtu, Wolverine, Two Sigma, Susquehanna, and others who provide the same role.

If you don’t let retail brokers charge market makers a fee for the order flow, then retail brokers would still likely route orders to market makers in order to receive the better execution they provide to retail investors, but without this revenue stream, retail brokers may need to just raise fees on retail investors, and market makers would make more money.

Without routing to an “internalizer” or “wholesaler,” retail investors will likely face bigger spreads, less liquidity, and higher fees as everything would get routed to a costly exchange or alternative trading system when market makers couldn’t provide the better prices to retail.

SEC Rule 605 requires that market makers publish their execution stats every month. Looking at the recent data, it shows that wholesaling saves customers money—$3.57 billion of price improvement in 2020 alone.

Where do we go from here?

As with many areas of capital markets that are not clear at first glance, trying to “fix” something based on a misunderstanding of how it works…will make it worse. More liquidity in our public markets is a win for everyone, and the complex system that we have today provides more liquidity than at any time in history—especially retail investors. It may be imperfect, but it’s extraordinarily effective.