At a16z, marketplaces represent one of our favorite business models. Our annual Marketplace 100 provides insight into the latest consumer marketplace trends across industries.

But we on the healthcare team have long lamented: why are there so few scaled consumer marketplace businesses in healthcare? There were four on the Marketplace 100 list this year (a record!)…but healthcare represents on average 12% of household spend. So shouldn’t we have more consumer health companies on this list?

Interestingly, all four healthcare marketplaces on the list focus on finding therapists. In fact, mental health was the fastest growing category by increase in spend on this year’s Marketplace 100. We thought we’d double click on this to understand: a) why mental health has emerged as a viable consumer marketplace category; and b) what other categories of healthcare may be conducive to big consumer marketplaces.

The healthcare industry’s laws of physics

First it’s worth unpacking why marketplaces might be harder to build and scale in healthcare than in other industries. We often talk about the unique “laws of physics” of healthcare, which certainly apply here. These include:

- The three-sided nature of healthcare (patient, provider, payor), and the related difficulty of integrating comprehensively with insurance across multiple carriers and provider networks

- The lack of price and scheduling transparency, and the unwillingness of a broad enough set of providers to publish prices and real-time appointment availability for all of their services

- The infrequent use of healthcare for the majority of consumers, making it harder to have LTV to justify the CAC

- Challenges around qualification of customers, given the inherent information asymmetry between consumers and providers in terms of exactly what diagnosis a consumer might have, and therefore, what specific service they might need

- Relatedly, the importance of referral behavior between providers, which can even be a requirement for insurance reimbursement; this can make the provider discovery problem less relevant in some specialties

Robust marketplaces match high volume consumer demand with dedicated supply, giving both sides the ability to transact in a self-service manner. But thus far, we’ve seen more “middleman” models in healthcare–where an intermediary helps match supply and demand, but without true self-service transactions.

Health insurance is an example of this. Insurance carriers maintain proprietary networks of providers with pre-contracted rates–but they do little to help consumers actually find the right provider, book appointments with them, and pay them for their services.

So what is it about mental health?

All four companies that made the Marketplace 100 list–Headway, Alma, Sondermind, and Path–are helping mental health professionals take insurance, and connecting them to consumers who need their services.

Most mental health providers historically have not accepted insurance. They’re often solo practitioners who don’t have the bandwidth to contract with each insurance company, and basic insurance contracts pay less than the provider could make by charging consumers directly.

New mental health marketplace companies propose to handle the complex logistics around insurance contracting and billing, and negotiate better payment rates than providers could get on their own. On the backend, these marketplaces are structured as MSOs (Managed Service Organizations) that deal with the logistics of insurance and other back office support services.

In mental health, the drivers of successful growth have been:

- Very high consumer demand driven by increased incidence of mental health issues during Covid, and the cultural destigmatization of therapy

- Widespread adoption of telehealth, propelled by both necessity during the pandemic, and favorable regulatory changes

- A historical dearth of therapists who take insurance, which has resulted in…

- …insurance companies that are desperate to expand their mental health provider networks, and are therefore willing to pay competitive rates to platforms that can expand their network coverage

The key element that makes these marketplaces work is the fact that they offer deep supply-side services that benefit both the provider (by diversifying their revenue stream beyond cash pay clients) and consumer (reduces out-of-pocket costs per appointment).

In a space where the consumer matches with one provider whom they see repeatedly, there is increased risk of disintermediation, absent any other reasons to stay with the marketplace platform. But in the case of mental health, the therapist and consumer are unlikely to cut out the platform because that would mean losing the ability to get insurance coverage, as the insurance contracting, billing, and payment operations are managed by the marketplace companies.

There’s also a network effect that drives stickiness; as the marketplace onboards more supply (and therefore demand), they can contract with more insurance carriers and negotiate better rates with them–making the platform more compelling for all sides.

What will make other consumer healthcare marketplaces thrive?

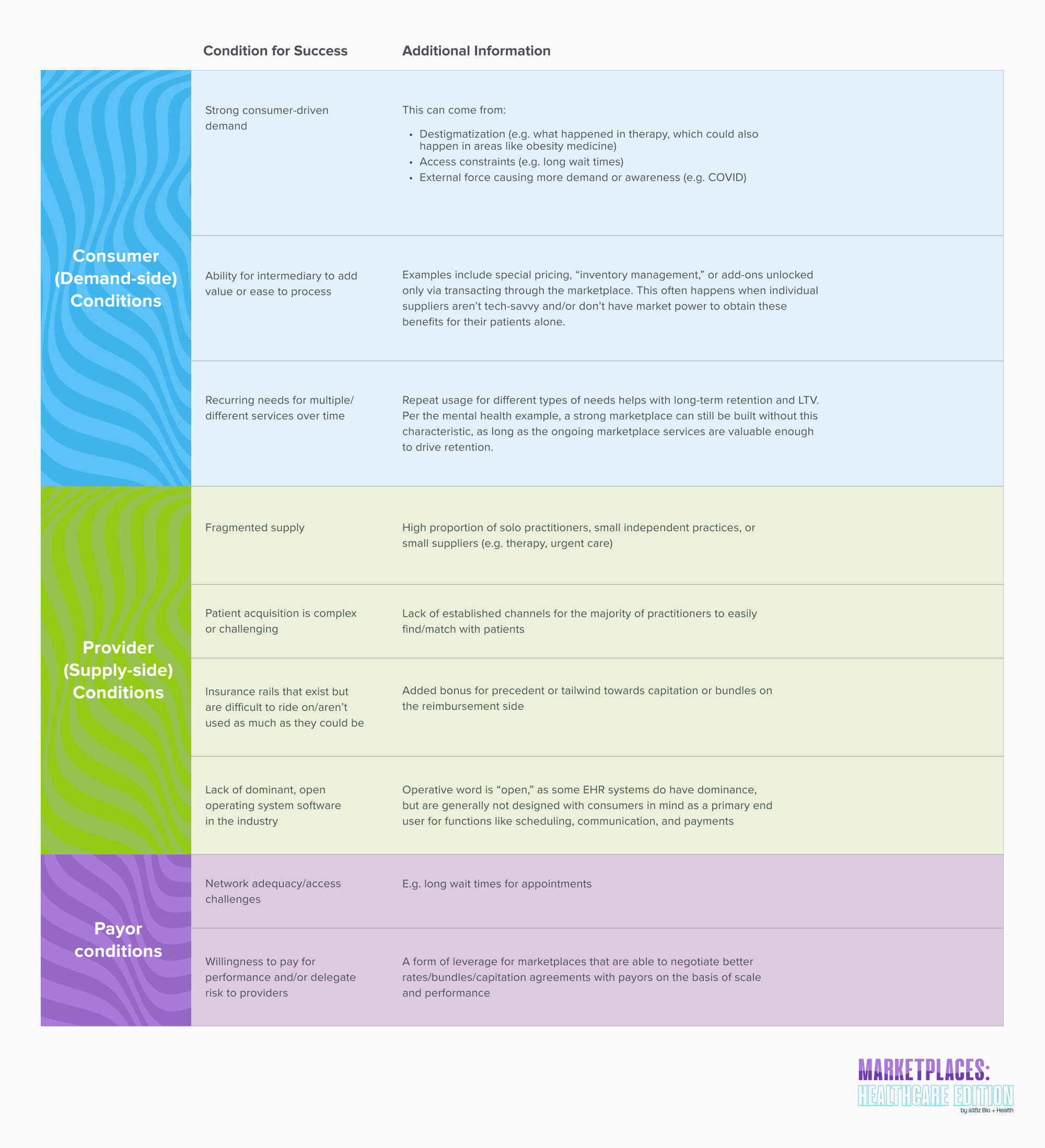

The mental health market naturally exhibits many of the conditions that we believe will drive successful consumer healthcare marketplaces. Those include the following (note that not all are needed for success):

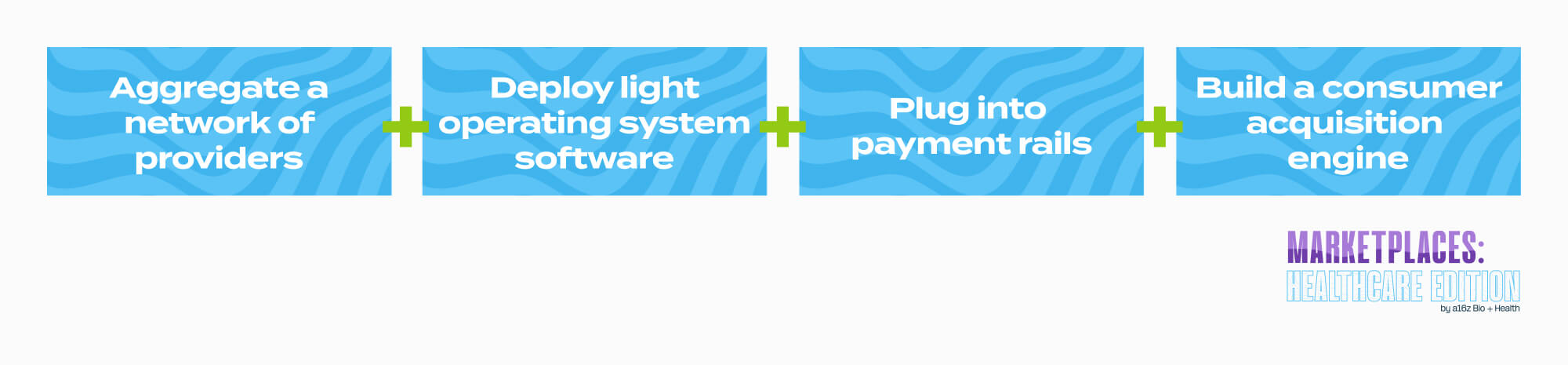

On the execution side, the following playbook for building a marketplace has worked in mental health, and we believe it can be replicated in other specialties:

- Aggregating a network of providers: This can be accomplished by providing value-added services that hit a key pain point for the providers, and by offering a network effect benefit that could otherwise not be achieved without being part of a marketplace.

- Deploying light “operating system” software: Marketplaces can provide software tools to providers and consumers that assist with things like scheduling, virtual visits, communications, referrals, and clinical data collection.

- Plugging into payment rails: This includes payor network contracting and credentialing, negotiating strong rates that could include capitation or bundles, processing claims and payment collection, or offering financing plans for the demand and/or the supply side.

- Building a consumer acquisition engine: This can be done through advertising, building a referral network, or creating a strong consumer-facing experience that organically attracts demand-side users.

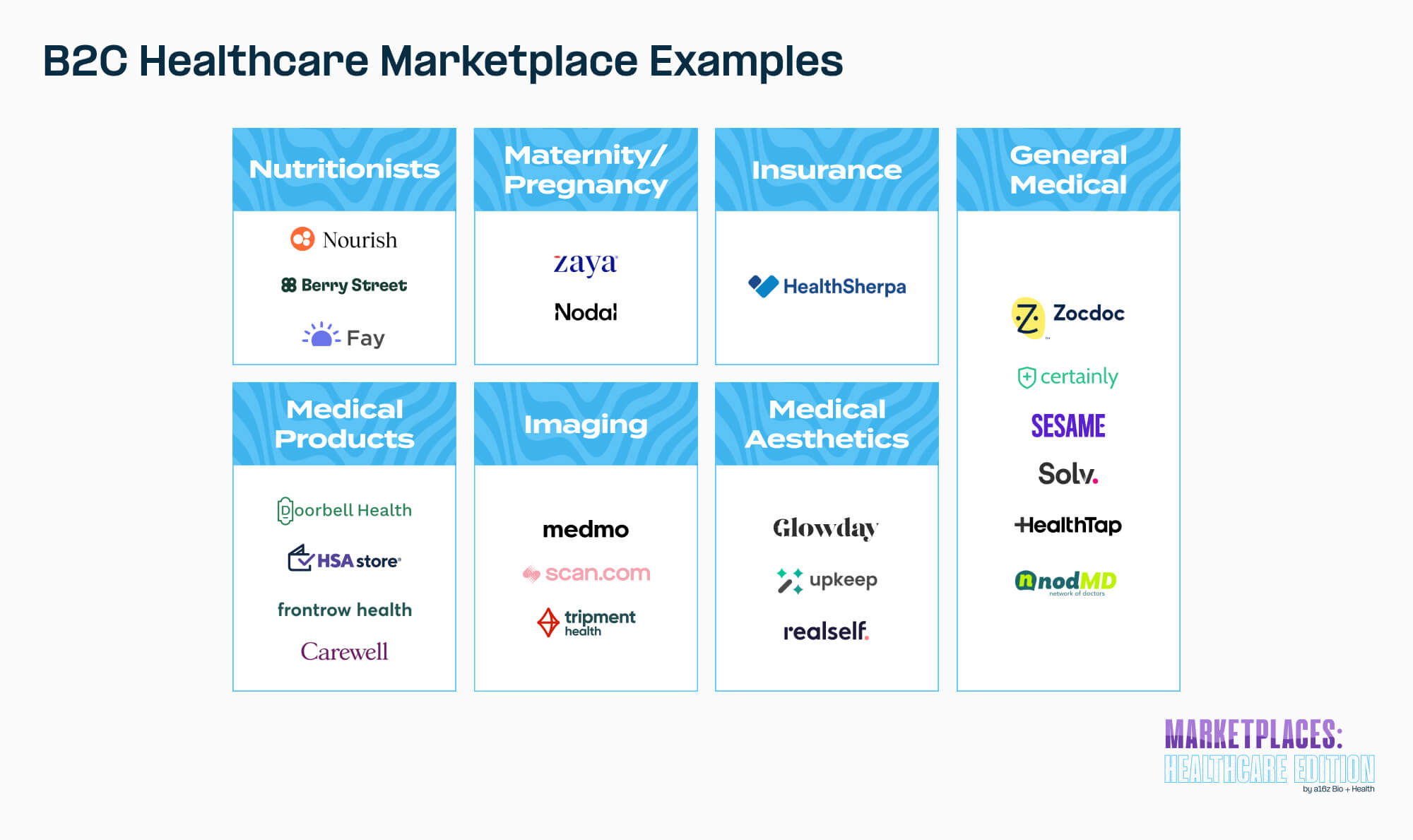

These frameworks can also be applied to medical products. We’ve seen a few consumer healthcare marketplaces that are aimed at specific product verticals with fairly high repeat behavior, like in the senior care items space, and for over-the-counter health and wellness products that qualify as HSA expenditures. Marketplaces can work well here when physical inventory is distributed across a wider set of suppliers, which makes it more difficult for one seller to hold and offer a wide SKU mix alone. This also often implies that the inventory is specialized (non-commodity items), so the marketplace can help aggregate and even provide additional fulfillment services, such as expanding the supplier’s shipping range or helping them activate automatic reorders.

We see consumer healthcare marketplaces as directly matching supply and demand in a way that the provider primarily owns the patient relationship. This means we’ve excluded platforms where the patient onboards to and pays for the service, and then is matched with or is able to select a provider after the fact.

Learnings from consumer marketplaces

A number of lessons from general consumer marketplaces apply to healthcare. Perhaps the most important is how to get both the demand and supply sides excited about participating in a marketplace.

Patients are worried about adverse selection, and may believe the best providers wouldn’t participate in a marketplace. And providers may feel they don’t need the additional demand, or are concerned about the quality of patient “leads” they’d be getting. We see three potential solutions here that might unlock a successful marketplace model, depending on the dynamics of the specific category.

Category type #1

Quality of supply matters up to a certain standard. No healthcare marketplace has quite the same dynamics as a platform like Uber, where supply has been essentially commoditized. Beyond a base level of safety and reliability, the quality of the driver is somewhat marginal in terms of passenger experience–ETA and price matter more.

However, there are likely some healthcare categories that live close to this end of the spectrum, where patients are looking for a provider that is qualified enough to solve their problem, but the difference in experience between the median provider and the 90th percentile provider is less stark. Lab tests and urgent care might fall into this bucket. It’s important to have these services done in a safe and certified environment, but beyond that, availability, location, and cost likely matter more to the patient.

In these scenarios, a marketplace’s role is to show the demand side that the supply meets that basic qualification bar, and offer transparent availability and pricing information. Uber background checks their drivers and displays a driver’s rating and number of trips completed to the passenger. For a healthcare marketplace, this will likely involve confirming credentials, but also might involve displaying reviews from patients, average wait times, and percentage of fulfilled appointments.

Category type #2

Quality of supply is paramount–and these suppliers can be brought online. In some categories, having the best provider does matter, as the marginal difference between the median and 90th percentile provider is much larger. And getting these best providers to list themselves online is much more achievable than it might initially appear, because the service selection motion is highly elective, or consumer-driven, versus physician referral-driven. An example would be certain elective surgical procedures, like hip replacements or cosmetic surgery; mental health therapy falls into this category as well.

The challenge, then, is to convince patients of their quality. On traditional consumer marketplaces, quality is often conveyed in three ways: (1) objective data, (2) subjective reviews, and (3) the platform’s own (sometimes manual) credentialing of the top sellers. A classic example is Airbnb. A seller’s profile typically includes their response rate and response time (objective data), feedback from past guests (subjective reviews), and, if they qualify for it, the “stamp” of being an Airbnb Plus host who meets extra criteria and quality bars (the platform’s own credentialing).

For healthcare marketplaces, this might include things like special qualifications, reviews or testimonials from other doctors they’ve worked with, or the platform’s own assessment of the provider’s procedure volume and quality of outcomes. For recurring services such as therapy, objective data could include benchmarking around the percentage of patients who rebook or retain with the provider (over a reasonable time period).

Category type #3

Quality of supply is paramount–but these suppliers are reluctant to come online. In this last category, quality of supply is also crucial, but quality suppliers are less likely to want to join a marketplace. This can be for a few reasons, some of which are more “fixable” than others:

Lack of demand generation need

Some providers are consistently overwhelmed with demand–and they will likely be the hardest to get onboard a new marketplace. One wedge is to approach them with SaaS tools to manage their practice (scheduling, automating follow-ups, procurement) or financial services (factoring, BNPL) that can improve their existing business.

Over time, a marketplace may be able to “drip” in new patient leads that they source once they are already embedded in the provider’s practice workflows.

Brand perception

Some high-quality suppliers may be reluctant to list on marketplaces as it feels like a negative stamp on their brand, especially if they are displayed alongside what they perceive to be lower quality providers. An example of this in traditional marketplaces is Amazon, which many premium brands have historically avoided.

In these cases, it almost always comes down to the branding and curation standards of the marketplace itself. Can the marketplace commit to vetting and onboarding only the best providers? If so, there are ways to give providers confidence around this? One example is only onboarding new supply (especially in the early days) via referrals from providers who are already in the network.

Concerns around demand quality

Some providers may be concerned that a marketplace will provide them with lower quality leads, or leads who no-show. From the consumer marketplace world, an example of this is high-end sneaker merchants experiencing fraud on the buyer side of eBay, as described in the Marketplace 100 podcast. These merchants would successfully ship an order–but then get chargebacks on (fake) claims that the sneakers were knockoffs!

A version of this in healthcare has to do with information asymmetry–consumers may not know exactly what kind of doctor or service they need for their condition, and end up booking with the wrong type of doctor, thus wasting a visit (and, potentially, fees) while needing to rebook with a different provider. A marketplace can add value here via “vetting” demand, either manually (ex. a quick call with the prospective patient) or in an automated way (ex. a self-service triage app).

There are likely other supplier protections to be built specifically for healthcare, similar to what StockX did for sneakers in inspecting each pair themselves. This might include not charging the provider for leads that end up needing to be referred elsewhere. Marketplaces could also implement no-show fees to discourage that behavior on the consumer side, as well as features that notify consumers with future appointments who may want to take a sooner slot that gets canceled, so that the provider’s schedule stays dense and productive.

Conclusion

We strongly believe there is a trillion dollar opportunity in becoming the front door to healthcare—the marketplace where consumers go to find and book appointments across multiple conditions and specialties, buy the lowest cost drugs, and even shop for insurance. We’re optimistic that upstarts with the characteristics described above could break out and achieve this in a way that mirrors the success of those that have landed on Marketplace 100. We look forward to seeing more than 4 consumer healthcare marketplaces on the list in the years to come!

-

Daisy Wolf is an investing partner on the Bio + Health team, focused on consumer health, the intersection of healthcare and fintech, and healthcare software.

-

Olivia Moore is a partner on the investing team at Andreessen Horowitz, where she focuses on AI.

-

Connie Chan is a General Partner at Andreessen Horowitz where she focuses on investing in consumer technology.

-

Julie Yoo is a general partner on the Bio + Health team, where she leads investments into companies that are transforming how we access, pay for, and experience healthcare.