This article is the first of four installments in our new series, How Fintech Companies Can Simplify Their Funding Strategy.

One of the most common conversations we have with fintech entrepreneurs looking to launch a new financial product is about determining the right strategy for funding their business. Whether you’re a vertical software company looking to launch a factoring product (selling accounts receivables at less than par), or a fintech lender trying to finance a new asset class, choosing the right funding structure can have a meaningful impact on the trajectory of your company, its ability to scale, and your bottom line.

In our new four-part debt series, we’ll walk through 1) choosing the right funding structure, 2) defining key terms and tradeoffs to know when negotiating a debt facility, 3) preparing and executing on a facility, and 4) managing and reporting on a facility once it’s in place. Our goal is to give you all of the tools you’ll need to set your fintech company up for success.

To start, in this article, we’ll first focus on breaking down the various funding options that you might want to consider. Then, we’ll walk you through how to choose the most appropriate option for the financial product you’re looking to bring to market.

Before we begin, we’d like to acknowledge that most of the following advice is oriented around helping you avoid using equity as financing strategy for your new financial products. Instead, we wish to identify other options that can help you preserve your runway and avoid significant dilution. We also suggest applying a simple rule to your consideration of any first funding structure: the simpler the better, for as long as possible. By going with what’s “simple” for your first facility, you’ll lighten the operational complexity of managing the facility while having more time to focus on your product and build asset performance.

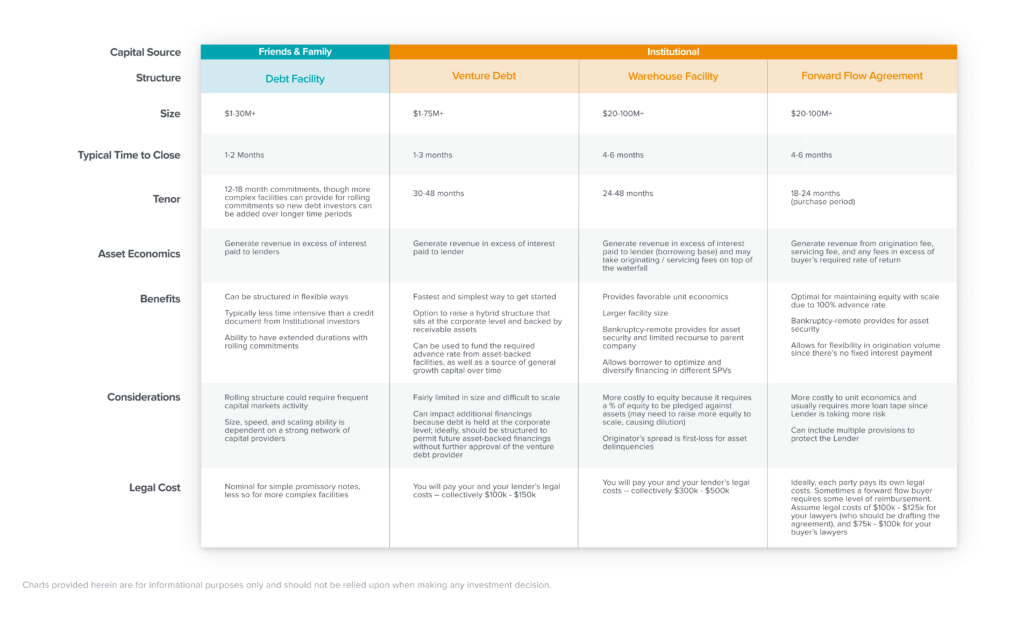

At a high level, there are four potential structures that many consider when launching a new financial product. Depending on whether you’re raising capital from friends and family (a network of high-net-worth individuals, or HNWIs) or institutional investors, they include:

- Friends and Family: Raising capital through family, friends, and HNWIs

- Debt Facility: Capital using some type of debt instrument, which can range from the very simple (e.g., corporate-level promissory notes) to the more complex (e.g., a structured facility offered through a special purpose vehicle, or SPV)

- Institutional: Raising capital through banks, credit funds, and other institutional investors

- Venture Debt: A term loan or revolver to fund assets, which sits at the corporate level

- Warehouse Facility: A bankruptcy-remote special purpose vehicle (SPV) — that is, a separate entity that protects the parent company from losses in the event that a particular pool of assets don’t perform, since the risk lies within a separate entity — that holds capital and assets

- Forward Flow Agreement: An agreement where the buyer agrees to purchase assets within specific parameters from the originator

Another structure, which is often discussed, but is rarely implemented, is an investment vehicle, whereby an originator raises a fund that will invest in the assets it originates. This structure seems ideal in concept, because capital is more permanent and terms can be more flexible (avoiding covenants and other restrictive terms that often accompany institutional facilities). However, such a structure raises several legal questions, including whether the originator would need to register as an investment adviser. It also limits diversification to the amount of capital raised per fund (which for an early stage business is typically fairly modest). Given these considerations we won’t spend time discussing this structure below.

To understand the basics of debt financing, it helps to have working knowledge of asset-backed debt—if you need to catch up on the topic, check out our post on 16 Things to Know About Raising Debt for Startups. We’ve laid out some core comparisons across each funding structure below.

Each facility comes with different tradeoffs. Note that early founders typically focus on facility cost (i.e., interest rate and fees). Cost, however, will depend on capital markets conditions and the predictability of asset performance. While cost is an important consideration, it should also be viewed in the context of other terms that you will negotiate. We’ll go deeper on how to think about these trade-offs in our next installment.

What makes the most sense, structurally, for your first product will depend on 1) the duration of your product, 2) your scaling plans, 3) loan predictability, and 4) your speed to market. These factors will impact the type of facility that’s available, which in turn has tradeoffs for economics, equity, and risks. Let’s take a closer look at these four factors.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Duration of your product

TABLE OF CONTENTS

First, the duration of your financial product is a key litmus test for choosing a funding structure. How quickly capital turns over can impact how much you’re willing to tie up your own equity to finance those products vs. needing to find off-balance sheet sources of funding. Below, we’ll describe some of the considerations for fintech companies originating shorter (<1 year) working capital oriented products, medium-term loans (1-5 years), as well as longer-duration assets (5 years+).

– For short-duration assets: Working capital-oriented financial products like cash advances, charge cards, factoring, and other forms of receivables financing, typically have <1 year durations and have the benefit of turning over quickly. Given the short duration of these products, many founders choose to keep more of these assets on-balance sheet and leverage their own equity (as you can recycle that capital multiple times in a given year). Note that short duration assets are also ideal for new, esoteric products, as they allow you to test asset performance more quickly and provide loan tape (loan origination data) to institutional lenders.

The most common paths to funding shorter-duration assets are either venture debt or warehouse facilities. Venture debt can be a great short-term solution, but it is unlikely to be a long-term funding option for a few different reasons. First, venture debt providers will typically only extend a portion of equity raised. Second, the debt sits senior to your equity (at the corporate level) and doesn’t benefit from being backed by assets exclusively. With this in mind, many entrepreneurs choose venture debt as a quick option to get started and build a track record, but with the goal of transitioning to a warehouse facility.

With a warehouse facility, lenders typically require an advance rate (often 80-95%), which means that you will be required to commit 5-20% per dollar borrowed in equity (and take any first losses). Combining venture debt with a warehouse facility can cut into this equity need, but note lenders typically want to see the company have some “skin in the game.” We’ll go into more detail on how to think about the tradeoffs of these terms in a future debt series post.

A forward flow agreement, on the other hand, typically isn’t preferred for very short-duration assets due to the time it takes for buyers to purchase assets from the originator. For example, if a lending product is 10 days and the buyer purchases loans from the originator every day, but an ACH payment takes 1 day on a 10-day receivable, then they’re losing out on 10% of the return. Buyers are also wary of the operational burden associated with the purchase of very short-duration assets.

– For medium-to-long duration assets (1-5 years): If the pricing your buyer offers is appropriate, it typically makes sense to consider an entirely off-balance sheet option like a forward flow agreement. The key consideration here is the time the equity capital would be locked up in the asset for a warehouse facility or using venture debt. For example, If you originate 3-year loans, your equity capital would be locked up in the asset for 3 years until the principal is paid back. If you originate $100M of loans with a 90% advance rate, then you would need to lock up $10M of the company’s cash over a 3-year duration. This would be a very inefficient and expensive use of equity capital and potentially require the company to take on a lot more dilution in order to fund additional originations. However, note that your buyer will require a risk premium for longer-dated assets, so you will always need to weigh any such dilution against the pricing being offered by a forward flow buyer.

Typically, in a forward flow agreement, the fintech company charges the customer an origination fee and then sells the whole loan (typically at par) to a debt buyer and charges an ongoing servicing fee. The benefit to this approach is that you don’t need to use equity to fund growth; however, you will miss out on the net-interest income that the assets may generate in a warehouse facility (as the buyer will capture that premium given it is taking all the risk of asset non-performance). To illustrate how dramatically one can scale without requiring much equity, at Bond Street, we were able to access over $900M in debt capacity via forward flow agreements while only raising $11.5M in equity.

– For long-duration assets (5+ years): These can be some of the most difficult to finance for young startups, so tread carefully. Being required to keep a significant portion of these assets on-balance sheet can cause significant dilution / tie up valuable working capital. With this in mind, it’s very important to either have an asset that you believe can generate significant enough yield to attract a third-party lender (i.e., double-digit net unlevered returns) or one that a lender will be confident can easily be securitized with scale (i.e., student loans / mortgages). A forward flow agreement or warehouse facility with securitization, are likely the best options for these long-dated assets but can be difficult to access without being able to articulate predictability in asset performance.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Scaling plans

TABLE OF CONTENTS

How quickly do you expect to grow your originations? You want to make sure you can scale your origination volume within the capacity of your facility and take into account the amount of equity that will be required given the advance rate you’ve negotiated.

If you’re uncertain about the pace of your originations, then the most straightforward option could be to raise venture debt or a friends and family debt facility to test your loans, build your loan tape, and have negotiating leverage when you raise a larger facility. However, companies with significant existing distribution will quickly scale through the committed capital of their venture debt facility. What you’re solving for is consistently having the capital to deploy at the pace of your originations. If you can time it right, venture debt can also be a temporary option to build loan tape and build confidence in lenders to provide a larger facility as your originations scale. The same logic is true for a friends and family debt facility. If you have the distribution to quickly raise a facility from HNWIs, then it could serve as a viable path to build loan tape and eventually raise a larger asset-backed facility. Note that you’ll always want to have an eye on the pace of your originations and begin raising more funding capacity at least six months ahead of hitting your existing limit.

If you’re certain about a large, incoming volume of originations, you could try raising an asset-backed vehicle like a warehouse facility or a forward flow agreement. As mentioned, a warehouse facility may provide attractive asset economics (particularly for shorter-duration assets) and a forward flow could also serve as an attractive scaling option (particularly for longer duration assets). The size and terms of the facility will vary correspondingly to your asset performance, so if you have the ability to wait and build loan tape (i.e., testing the loans with venture debt first), then you’ll be able to receive more favorable terms than you otherwise might have.

Loan Predictability

How certain are you of your asset performance? Certainty of scaling plans typically goes hand in hand with certainty of asset performance.

If you’re not confident in the predictability of your performance, either because you’re originating a new / esoteric asset (or you just have limited funding history), it may make sense to pursue either a friends and family debt facility or a venture debt facility to build a track record.

If there’s some level of predictability around asset performance, for example, with an existing product that is being originated in a new way (e.g., factoring for a new market), then there are likely established institutional players who can help finance assets via venture debt or potentially an asset-backed facility.

When there is high confidence in the predictability of assets, either from existing loan tape or from key insights into the underlying credit profile of borrowers, then there’s a larger market of institutional investors including asset-backed debt investors that could be interested in funding your product. In that case, it may be worth committing time and resources to setting up an asset-backed facility where the risk would be transferred to a warehouse facility or to a forward flow buyer. However, warehouse facilities and forward flow will have protective provisions such as asset performance-based triggers and financial covenants.

Speed to market

And finally, how quickly are you looking to launch your product? Oftentimes founders choose to prioritize speed to market when faced with intense demand, competition, or other time constraints.

The absolute fastest route to launching a new financial product is to use equity, however, given the high cost and its finite resource – founders typically use this as a last resort (or as a temporary solution). When it comes to raising outside debt capital, the fastest routes are either raising venture debt or a friends and family debt facility. Venture debt can be raised quickly (following your last equity round), especially if raised from your bank provider, as much of the onboarding diligence is already taken care of. Many of these lenders also view venture debt as a bridge product they can use to graduate the company to a larger warehouse facility over time. A friends and family debt facility could also be an option, however, it requires a strong network of HNWIs to fundraise from. With both approaches, committed capital is typically fairly modest in size, and the risk of the assets usually sit at the corporate level. Warehouse facilities and forward flow agreements are longer-term solutions, though they usually take several months longer to set up.

We recognize that raising debt can be a confusing process. We hope that this piece provides you with a useful framework in navigating different funding structures. In our next piece, we’ll explore key terms and the tradeoffs you’ll need to weigh when negotiating your first credit facility.

This report contains debt terms and market insights compiled from discussions with numerous experts. Thank you to everyone at Atalaya, Coventure, Jeeves, Paul Hastings, Point, Silicon Valley Bank, Tacora and Upper90 who contributed to this research, with special thanks to Rich Davis and Eoin Matthews.

-

Nathan Yoon is a partner at Andreessen Horowitz in the Capital Network team

-

Melissa Wasser is a partner on the Capital Network team, focused on fintech companies.

-

David Haber is a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, where he focuses on technology investments in B2B software and financial services.