This was originally posted on the a16z Growth Newsletter on Substack. To receive analysis like this in your inbox early—plus additional media recommendations and insights from the Growth team—be sure to subscribe.

It’s no secret that every new platform shift ushers in a new set of winners. These new winners take advantage of both new technology infrastructure and new business models to far outpace financial models and consensus expectations. We call this breed of winners modelbusters.

We’re talking about modelbusters now because we’re going to see many, many more of these companies in the AI era. AI is the biggest platform shift of our lives, and we’re excited because it will create new ways of spending time as consumers, new ways of working, and new business models. The bigger the shift in UIs, amount of data accessed, and business models, the more the tech shifts favors the newcomer over the incumbent.

Before we discuss the current opportunities in the AI era, though, we want to spend the rest of this post breaking down the modelbusters concept—what modelbusters are, why they matter, what forms they take, and how their success is seen—so founders have a blueprint, along with a few gut checks to test if they’re on the path toward building a modelbuster.

Two forms of modelbusters

Modelbusters usually take one of two forms: companies with a larger-than-anticipated TAM and companies that add product lines that open up even more opportunities for their business. These two forms aren’t mutually exclusive; some companies have started as one type and turned into both. And though not all modelbusters are category creators, almost all successful major category creators are modelbusters. Though we won’t get into the nitty-gritty of each company’s business here (stay tuned for those), we’ll walk through several examples at a high level to give you a sense of how and why they’ve outperformed.

Larger-than-anticipated TAM

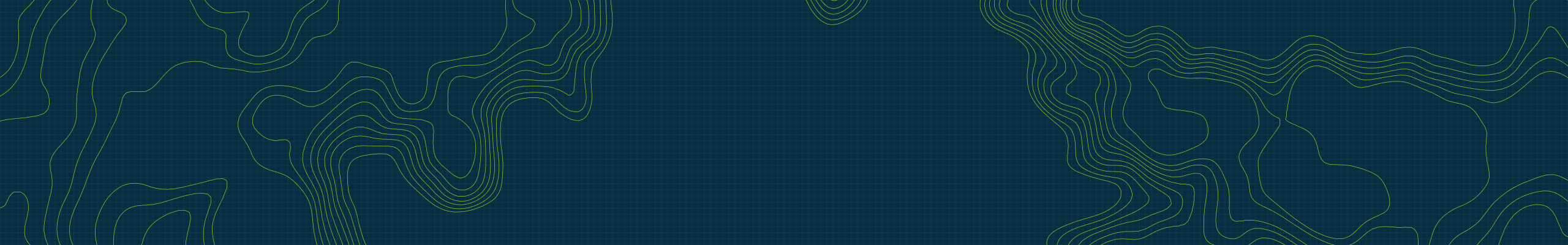

When there are platform shifts and 10x better products come to market, everyone consistently underestimates how fast and broad the adoption can be. Take Apple and Roblox* as examples.

iPhone

When the iPhone launched in June 2007, Steve Jobs said it would roll three separate devices into a single product and reinvent the phone. Still, plenty of analysts thought it was a gadget that would serve a small niche of high-end executives and tech enthusiasts, and they passed off Apple’s own sales target—10M units by calendar-’081—as aggressive. Fifteen months later, however, the company had already blown past that estimate and vaulted to the #3 mobile phone vendor worldwide, leap-frogging Sony Ericsson and LG in the process.

Apple was probably the biggest company in the world, covered by practically every analyst, and everyone still underestimated the opportunity by nearly 3x. The models missed the TAM in three key ways: 1) reenvisioning the phone experience did expand the TAM beyond tech enthusiasts (turns out everyone wanted a phone in their pocket), 2) Apple built a robust App Store ecosystem on top of iOS, which created strong network effects and a massive monetization opportunity for the company, and 3) the iPhone’s UX delighted customers, making it painful for them to switch to other phones while also encouraging them to upgrade their devices year over year in to gain access to new features.

Roblox

When we first invested in Roblox, it was largely viewed as a rudimentary gaming platform for young kids, which was obviously a niche with a limited lifetime value. But Dave Baszucki didn’t imagine Roblox as a kids’ toy: he saw it as a cloud-native developer platform and virtual economy capable of “growing up” with its users.

He spent over 15 years building out rich creation tools and an integrated, self-contained marketplace so that any user could become a creator and earn money on their own experiences at a cost of under $0.10 per user-hour (or free, if they chose!). This marked a sea change in the kind of entertainment available to consumers, since it was a fraction of the cost of any other entertainment on the market—which ultimately incentivized more users to join the platform.

That upfront investment paid off with a powerful user-generated flywheel. As more players joined, developers had the incentive and the tooling to build more sophisticated games for older age brackets. What looked like a child-only audience turned out to be a springboard to an “over-13” segment that exploded to 61M daily active users and now grows almost three times faster than the under-13 base (36% YoY vs. 13%).2 Now, they’re building products for the over-21 audience.

In short, this platform-enabled flywheel created better games, more engaged users, stronger expansion to other cohorts, and ultimately, a financial performance that far outpaced what anyone would’ve modeled.

New products unlock new opportunities

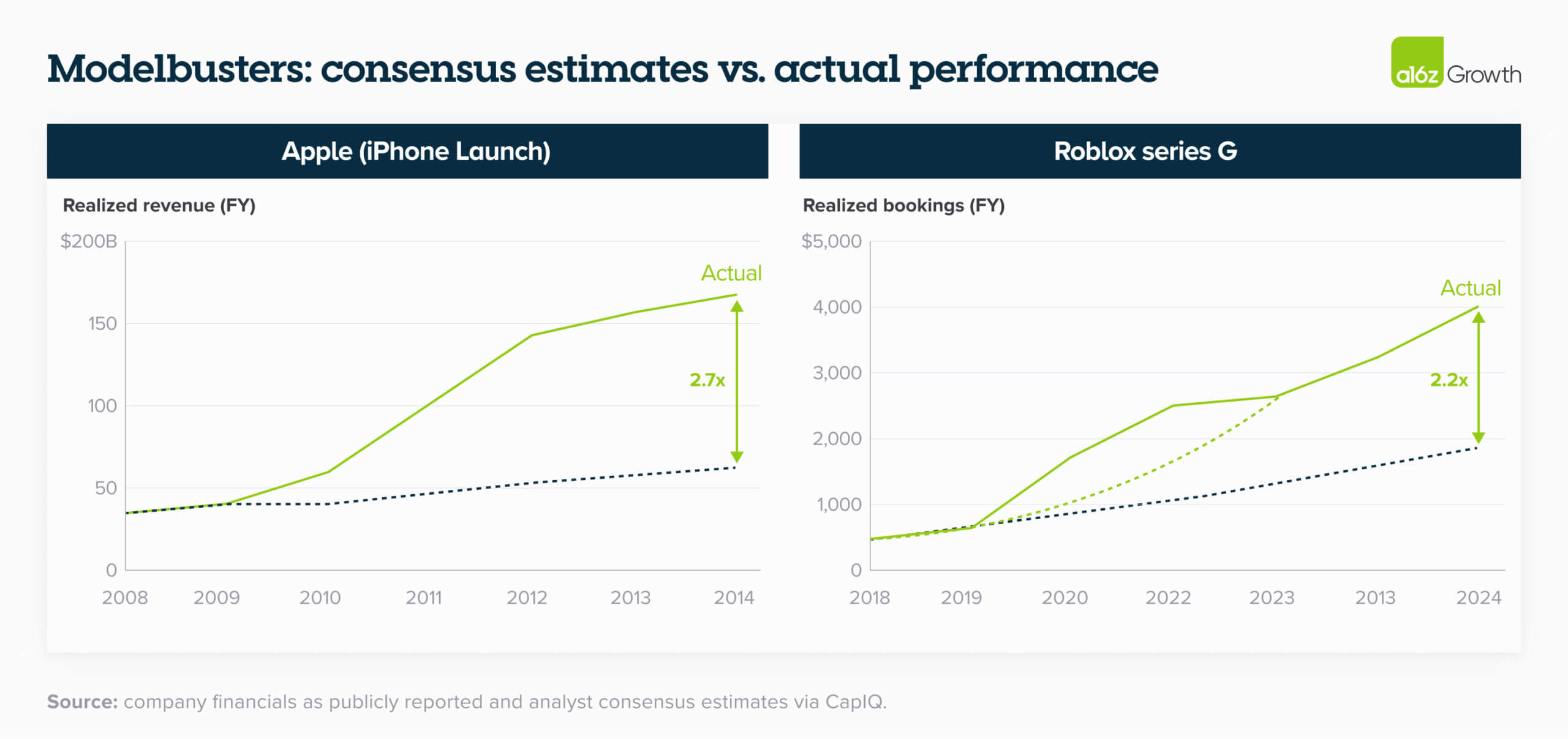

Other modelbusters launch new products that allow them to serve adjacent markets or capture more wallet share from existing customers. (Many of these companies are what we’d call true platform companies, but we’ll dive deeper into their specific characteristics in a separate post.) Let’s look at CrowdStrike and Anduril.*

CrowdStrike

Back in 2019, most sell-side analysts pegged CrowdStrike as a cloud-native endpoint-security consolidator—essentially the next Symantec or McAfee replacement with a capped TAM for “legacy” antivirus (AV) users. Founder George Kurtz saw something much bigger: he believed that CrowdStrike could grow into a cross-category, cloud-based security platform.

Years before starting CrowdStrike, George had built an antivirus startup that he sold to McAfee, and he knew from experience that traditional antivirus software wasn’t sufficient to prevent endpoint attacks. Cloud was just taking off, and he bet that companies would need cloud-based agents to do the monitoring for them. So, he invested early in building an architecture that would support these agents, sacrificing his short-term margins for a unified data pipeline. Unlike legacy AV tools that shipped periodic signature updates, CrowdStrike’s agent continuously streamed rich telemetry to the cloud, enabling real-time detection, response, and analytics far beyond what on-prem scanners could offer.

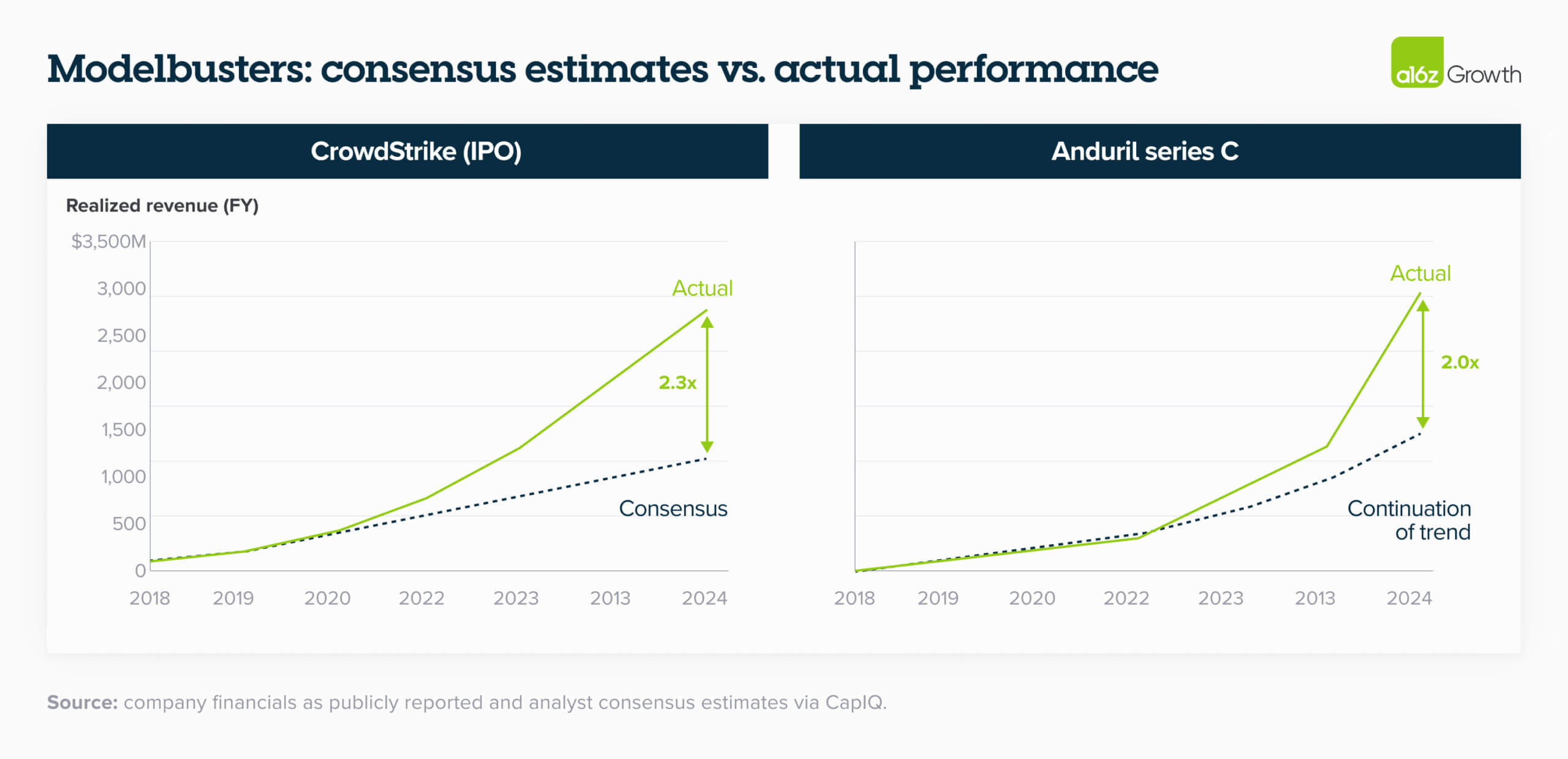

This early bet allowed CrowdStrike to win in the AV category and also laid the architectural foundation for every subsequent security module that CrowdStrike released on its Falconer platform, from threat hunting and identity protection to IT hygiene. George was also fanatical about innovating in house to edge out the competition in adjacent markets; he’d do things like offer engineers time off to ideate on new product ideas and give stock to the winners. Whereas CrowdStrike’s competitors needed to bolt on new products and modules through M&A in order to build out their product suite, CrowdStrike built 29 modules organically. And because those modules all relied on the same architecture, CrowdStrike could simply flip them on in the console with no extra installs or integration, which made cross-selling much easier. Eventually, this allowed the company to redraw a previously narrow category like AV into the much more robust endpoint detection and response (EDR).

The payoff shows up in the numbers: 48% of customers now run 6 or more of CrowdStrike’s modules, fueling roughly $500M of net-new ARR annually without adding a single new logo.3 CrowdStrike’s expansion into other products meaningfully expanded their addressable market and extended their ability to compound at high rates, which led to revenue outpacing sell-side consensus—growing at over 2x the modeled rate.

Anduril

Some modelbusters’ innovation engines don’t open up adjacencies or new customers per se; they open massive opportunities that others just wouldn’t be able to capture. In Anduril’s case, they used Silicon Valley-style product innovation, a software-native business model, and procurement know-how to leapfrog other startups and break into the innovation-averse Department of Defense, unlocking a $3T budget in the process.

Before Anduril, the innovation burden in defense lay with the DoD: the DoD sketched out the products they wanted, let defense contractors bid on it, and paid those contractors on a cost-plus basis. Unsurprisingly, this led to a lot of bloated spend, inefficiency, and delayed timelines. Anduril turned this business model on its head by building their own products, without a DoD contract, and selling them into the DoD themselves.

While this product-first thinking definitely carried upfront risk for Anduril—they weren’t getting reimbursed for any of their products by the DoD—it tightly aligned the company’s economics with rapid innovation and iteration, which ultimately provided the DoD much more innovative products than they’d get otherwise. It also allowed the founders to take advantage of the move to the cloud and build its autonomy stack, Lattice, as a cloud-native, sensor-agnostic software platform that lives across datacenters and “tactical edge” sites. By streaming rich sensor feeds from its different products into Lattice, Anduril enabled real-time AI model training, mission planning, and software updates at scale, which would be impossible under the old one-off, cost-plus model.

And when it came to selling their products into the DoD, Anduril’s founders leveraged their experience navigating the defense procurement process at Palantir to secure a “Program of Record” status across multiple product lines. This allowed the company to sell newly built offerings through a streamlined procurement channel, giving them a distribution leverage that’s nearly impossible for other startups to match. Plus: since all of Anduril’s products run on the same cloud-native Lattice OS, Anduril can cross-sell upgrades, intelligence services, and new autonomy features across programs and turn discrete contracts into a unified revenue stream across the DoD’s diverse procurement lines.

Fast forward to today: Anduril has been able to cross-sell its 35+ products into artillery, ISR, and electronic-warfare budgets with massive spend categories still left to tap.

How do you know if you’re building a modelbuster?

Though the companies we mentioned above are all built in very different sectors, they highlight the key commonalities between all modelbusters: what—not how—products; pull—not push—markets; network effects in some of the best cases; and strong compounded growth.

What? > how? products

Though spreadsheets and financials can signal if you’re on the path toward building a modelbuster, you won’t know if you’re on track from those alone. You also need to know the markets, live in the products, and be fluent in consumer behavior.

Generally, modelbuster products are “what?” products, not “how?” products. “What?” products fundamentally reimagine existing products or present entirely net-new capabilities. Think of the iPhone, Anduril creating entirely new defense products with no modern competitors, or Roblox’s cloud-based, developer platform and innovative gaming economy. “How?” products, on the other hand, innovate on the delivery method. That might look like being the first company to sell a particular brand of shoes online. You might eke out a competitive advantage now, but that’ll be competed away once others catch on. Focus on the “what?” products: fundamental innovations are much harder to compete with.

Pull, not push, markets

Customer love is one of the best predictors of whether a founder’s company will grow into a modelbuster. While it’s important that founders have a strong POV on how their product uniquely delights customers, we want to hear from customers that the founder’s vision actually connects with them. In fact, David keeps a Post-It note on his computer that says, “is the market demanding more of your product?” If it is, it’s likely you’re a company that “pulls” in customers instead of “pushes” your product to them. If your customers are drawn to and love your product, chances are they’ll likely stick around and buy even more of it.

This customer love shows up as best-in-class gross and net retention. CrowdStrike’s numbers are a good reminder of this: the company has 97% gross retention and 112% net retention on a $4B+ ARR base.4

Network effects

Network effects are the strongest form of competitive advantage: they compound your lead in the market by building competitive moats. Every new user, data point, or integration makes the product better, lowering acquisition cost and accelerating adoption much faster than linear models can capture. (Just look at Roblox.)

Network effects aren’t a required ingredient for modelbusters, since they’re generally associated with marketplaces. If a company doesn’t demonstrate network effects, strong market leadership + brand + go-to-market excellence is a close second when it comes to competitive advantage.

Strong compounded growth

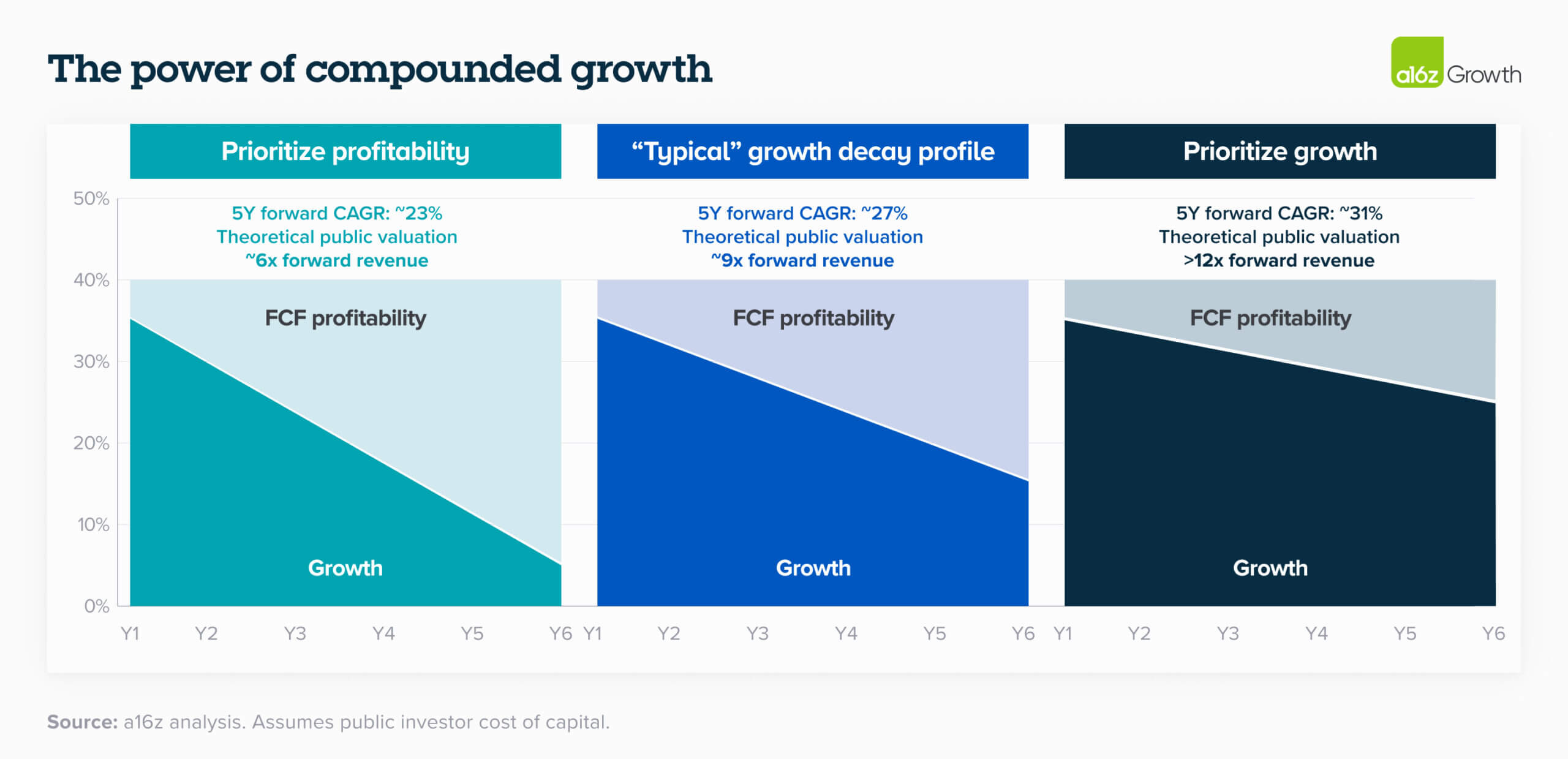

The magic of modelbusters lies in the power of compounded growth: they grow faster and for longer than any financial model could anticipate. Over the long haul, driving faster revenue growth boosts your company’s current valuation much more than targeting higher profit margins.

If we use the traditional rule of 40 framework, assume that companies can trade off a point of margin for a point of growth, and standardize the premium markets attribute to growth, every point of growth is worth ~2x more than a point of margin.

This doesn’t mean founders should only focus on growth. But high valuations today come from expectations for high future growth above all else.

The next generation of modelbusters

As we mentioned at the top of the post, we believe the AI opportunity is massive. The AI infrastructure buildout we’re already seeing is on pace to invest over $1T in a 5 year span, greater than all of the US shale industry in the early 2010s, the broadband buildout in the late 1990s, or the Apollo space program in the 1960s.5 This generation of AI companies is the fastest growing the world’s ever seen and we’ve started to see some business model shifts, which makes us confident that we may see more creative ones crop up soon. We’ll unpack these dynamics, and how we believe the AI supercycle is laying the groundwork for a new generation of modelbusters, in our next post. Stay tuned.

*a16z Growth portfolio company

- 1 Jobs: Apple Is Third Largest Handset Supplier.

- 2 Per Q1 2025 supplemental materials provided by Roblox.

- 3 Per CrowdStrike Q4 FY 2025 reported earnings.

- 4 Per CrowdStrike Q4 FY 2025 reported earnings.

- 5 Analyst estimates and public company filings from CapIQ.

- 6 Based on analysis of Pitchbook Data, Inc. and SVB analysis as of April 2025.