Generative AI is Coming for Insurance

Joe SchmidtBecause underwriting, selling, and servicing rely so heavily on humans processing large quantities of written or verbal communication, existing tools have struggled to properly automate these services and materially impact loss ratios (losses on written premiums) and expense ratios (underwriting and servicing written premiums). Large language models (LLMs), with their ability to proficiently collect and distill large amounts of data, could change this as they can augment or fully replace the process of a human combing through large amounts of data.

While current machine learning technology allows for improved decisioning on simple products like auto and home insurance, more complex underwriting processes like commercial and life insurance remain challenging. This has less to do with the process of decisioning relevant data and more to do with collecting and synthesizing the relevant data. While traditional ML models have helped dramatically improve more standardized underwriting processes like home and auto, LLMs could potentially help with the more complex group by gathering data to help underwriters make better decisions, especially in more intricate cases like large commercial policies where more context and follow-up questions are required. For example, most large commercial policies cover dozens or more locations, and each location has specific nuances (such as electrical panels, fire doors, sprinkler density/effectiveness, management effectiveness, amount of combustible storage) that must be gathered from the applicant, understood by the underwriter, and evaluated against underwriting guidelines. LLM-powered workflow software for underwriters could drive down underwriting time and cost while increasing accuracy.

On the sales side, considered purchases, like life or disability insurance and annuities, are primarily sold offline through human agents and brokers because they’re complicated products that buyers often have questions about. (Consumers are quicker to buy mandatory insurance products, like home or auto insurance, online.) LLMs trained on customer data or materials on what policies are appropriate for a certain customer situation could help answer complex questions for consumers about what policies they should buy and how that policy might impact their unique needs.

And finally, carriers and agencies employ large policy-servicing divisions to help with changing policies, customer support, and claims, as well as “internal wholesaler” teams to constantly monitor and service the production of affiliated agencies or brokerages. Think of these as vertical-specific call centers where a representative needs to distill what a customer, agent, or broker actually needs during a conversational dialogue, and either respond with the answer or enter the appropriate information into a system. Allowing LLMs to manage some of these conversations could dramatically improve efficiency and profitability.

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable Seema Amble, Joe Schmidt, and Brian Roberts

- Investing in FurtherAI Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- Oil Wells vs. Pipelines: Two Strategies for Building AI Companies Joe Schmidt and Angela Strange

- From Demos to Deals: Insights for Building in Enterprise AI Kimberly Tan, Joe Schmidt, Marc Andrusko, and Olivia Moore

- Trading Margin for Moat: Why the Forward Deployed Engineer Is the Hottest Job in Startups Joe Schmidt

Opportunities & Risks with Third-Party Payment Links

Sumeet SinghFor the first time in more than a decade, Apple’s stronghold on app distribution and monetization may be threatened, as a U.S. appeals court confirmed in April 2023 that Apple can no longer prevent third-party payment links in the App Store. The case dates back to 2020, when Epic Games—whose founder Tim Sweeney was a vocal opponent of Apple’s 30% revenue cut on all App Store purchases—attempted to bypass Apple’s payment system with their game “Fortnite.” Apple subsequently blocked “Fortnite” from the App Store.

Why is this such an important development? As we wrote in our piece on payments for high-risk industries, if developers gain the ability to embed third-party payment links in their apps, they will be able to directly see who their customers are and what their spending behaviors are like (something currently obfuscated by Apple). This will in turn allow developers to build deeper relationships with their customers, cross-selling them products and driving them to specialized offers and discounts—ultimately driving greater profits.

Additionally, if these third-party payment links allow developers to bypass Apple’s 30% take rate, developers could potentially deliver more value back to customers and drive greater loyalty. That said, it’s unclear today if Apple would budge on its take rate; in South Korea, for example, Apple has been prohibited from banning third-party payment links, but according to their own documentation, they still require developers to pay a commission fee of 26%.

However, there is one critical detail that most are overlooking here: namely, that Apple’s App Store acts as a merchant of record for its customers; that is, it accepts payments on behalf of apps available on the store. Merchant-of-record platforms are authorized and held liable for a given merchant’s transactions. These can include processing payments, managing all payment processor fees, dealing with financial institutions, managing refunds and chargebacks, providing billing-related customer support, and ensuring businesses remain compliant with global tax regulations—which can become very complex when a product is sold in different states and countries. The merchant of record’s name is what a customer sees on their bank statement, as it holds the processed amount for a short period of time before it’s transferred to the business. Companies like Stripe, Adyen, and PayPal, for context, are not merchant-of-record platforms, but rather payment service providers (PSPs). This means they do not fully abstract away global payment operations, nor do they take on the liability of actually remitting taxes even if they help calculate the amounts owed.

We’re likely to see an explosion of new apps that sell across the world, especially as the advent of generative AI drives down the cost of running a minimal viable venture and both mobile phones and local digital payment methods continue to penetrate new businesses. However, selling across the globe is becoming more complex given changing laws around the definition of where taxes are owed (i.e., the “tax nexus”) for digital products. For example, the U.S. now considers any state in which a company sells a product or service a tax nexus, even if they don’t have a physical presence in that state. Additionally, some countries have no minimum threshold for owing and paying taxes (e.g., India). While new software products can help merchants calculate the amount of taxes they owe in a given geography, they do not actually help with the remittance of said payments—which can be a massive undertaking to set up in-house.

If developers of these apps go in the direction of bypassing Apple’s payment infrastructure to gain the benefits described above, they will need to think through the merchant of record trade-off: whether they want to move in-house all of the functions and liabilities that are required to sell globally, or if they prefer to partner with a merchant-of-record platform that removes that complexity away from them.

- B2FI: Demystifying Software Sales Into Financial Institutions David Haber, Sumeet Singh, Brad Kern, and Katy Nelson

- More Countries, More Problems: Selling AI Products Around the World is Still Too Hard Sumeet Singh and Angela Strange

- Beyond Payments for High-Risk Industries Sumeet Singh and Seema Amble

- Financial Services Will Embrace Generative AI Faster Than You Think Angela Strange, Anish Acharya, Sumeet Singh, Alex Rampell, Marc Andrusko, Joe Schmidt, David Haber, and Seema Amble

- 2023 Big Ideas in Technology (Part 1) Connie Chan, Anne Lee Skates, Jack Soslow, Doug McCracken, Sarah Wang, and Sumeet Singh

Visa+, Interoperability, and Creating Clearinghouses for New Payment Methods

Seema AmbleLast month, Visa announced its Visa+ initiative to connect peer-to-peer (P2P) payment platforms. Launching later this year, Visa+ will allow users of different P2P payment services to pay each other directly after they create a personalized “payname,” or handle, to connect their accounts. The service will also create an interoperable path for third parties to connect to P2P customers through a single platform (e.g., allowing a merchant or platform to make disbursements via the P2P platforms). Visa+ will launch with Venmo and PayPal (even though, yes, PayPal owns Venmo, users can’t yet transfer money between the two services in real time…) and will add DailyPay, i2c, TabaPay, and Western Union as partners in 2024.

Visa needs to get a number of things right here, but if they succeed, there’s an interesting opportunity for them to become the clearinghouse for instant P2P payments, much as they are for card payments. More broadly, the introduction of Visa+ raises a question around the proliferation of payment methods and whether we’ll see more centralized clearing or consolidation.

With Visa+, Visa simplifies how merchants can receive payments; instead of having to integrate with three or four P2P providers, they can now (potentially) just integrate with one. The same applies for employers, who would prefer to integrate with just one wallet provider, not five. Visa’s involvement and additional layer of authentication also provides participating P2P platforms with some amount of fraud detection and securityIt also allows the company to strategically sit in the middle of all P2P transactions. This scenario can also potentially extend to cross-border use cases; for example, a user of a wallet that operates in the U.S. could send money to a Visa+ user in Kenya, even if the two wallets didn’t do cross-border payments.

For Visa+ to be successful, Visa needs to figure out how to convince consumers to create yet another payname and use the service. Part of this effort will be up to marketing, but the company also needs to open up a new use case for consumers, solve a common friction point, or both (e.g., if Visa+ made it easier for gig workers to receive payment). Visa+ also needs to account for the absence of CashApp and Zelle, which are used by 30-40% of the U.S. population), as well as major wallet providers like Google Pay and Apple Pay, from the service. Without these players, the benefit of participating in a meta layer is more limited. Visa, as it often does, can use marketing incentives to get these platforms to work with Visa+—though these benefits may not supersede the platforms’ desire to own their relationships with their customers (versus ceding it to a third party like Visa). This is especially true for EWS, the fintech company that owns Zelle and is itself co-owned by seven U.S. banks. Seeing as Visa was also originally controlled by a consortium of banks, EWS may not want to undergo a similar disruption.

Payments products take time to adopt. ApplePay, NFC-based cards, and other successful examples all took more than 10 years to gain widespread adoption. So, even if Visa can pull off the execution of this, I wouldn’t expect broad consumer adoption of Visa+ immediately, but it’s one to watch and see. Interoperability is also a theme that will emerge given the proliferation of consumer (and also B2B) payment options at checkout across wallets, BNPL, pay by bank, and more.

- Investing in Lio Seema Amble, James da Costa, Eric Zhou, and Brian Roberts

- Need for Speed in AI Sales: AI Doesn’t Just Change What You Sell. It Also Changes How You Sell It. Seema Amble and James da Costa

- Investing in Stuut: Automating Accounts Receivable Seema Amble, Joe Schmidt, and Brian Roberts

- The AI Application Spending Report: Where Startup Dollars Really Go Olivia Moore, Marc Andrusko, and Seema Amble

- The Rise of Computer Use and Agentic Coworkers Eric Zhou, Yoko Li, Seema Amble, and Jennifer Li

Featured Tweetstorms

a16z Partner Marc Andrusko on ModernFi’s takeaways from the FDIC’s overview of the deposit insurance system and potential options for deposit insurance reform.

a16z General Partner Alex Rampell on how a “consumer-signup robotic process automation (RPA)”—which AI can do—is the missing link to changing how friction/inertia preserves giant gross-profit pools in financial services.

More From the Fintech Team

Using Generative AI to Unlock Probabilistic Products

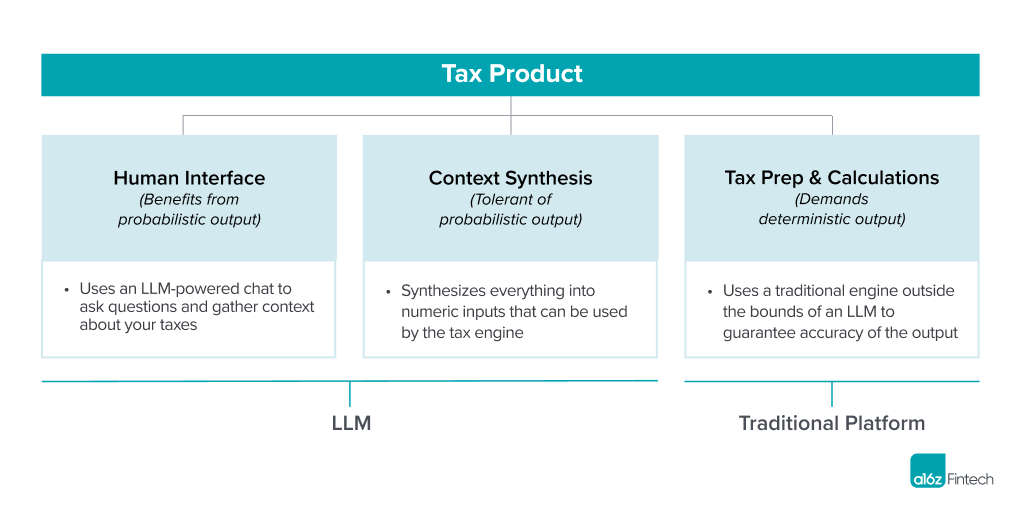

One remarkable thing about the invention of generative AI is that it’s one of the first examples of a probabilistic computer that produces outputs that are varied and non-deterministic. Some, who expect these systems to behave like traditional systems, have complained about hallucinations—however, these complaints miss the point. A dispersion of outputs (including hallucinations) is exactly what’s so special here. In fact, they unlock a whole new category of product design: probabilistic products.

Aligning Founder Superpowers with Product Cycles

Watching the generative AI space shape up over the past several months has reaffirmed my belief that, as product cycles mature, different types of builders have leverage at different moments in the cycle. And, at this early stage in generative AI, technologists and product pickers will likely have the biggest impact on which companies emerge as winners.

Bat Out of Hell: Identifying Your Durable Advantage in Fintech

Noninflationary acquisition channels only address the most obvious challenge for most fintech companies—growth—but ignore a key factor: differentiation. Differentiation is what ultimately distinguishes one product or service from another, and sustainable differentiation is differentiation combined with some sort of moat. Absent sustainable differentiation, even the most attractive channels (inefficient or budgeted) someday tap out, and Hell’s Flywheel starts spinning anew.

This post is a deep dive into the sustainable differentiation that results in a compounding flywheel, with a focus on financial services companies that sell commodity-like, nonphysical world products such as money, insurance, lending, or equity capital.

The Opportunity for Healthcare and Fintech

U.S. healthcare: it’s currently a confusing, costly, and inefficient system for patients, providers, and payers alike. The builders above are tackling this challenge from all angles: helping clinics get paid faster and more accurately, opening up access to mental health care through insurance, providing patients with the price of their treatment up front, expanding virtual and value-based care, and much more. The key to revamping our broken healthcare system, according to them, is modernizing the financial layer—what one founder calls “the secret sauce.”

To hear directly from six founders trying to reinvent the healthcare system with the help of fintech, check out “How Fintech is Reshaping Our $4T Healthcare Industry” at the a16z podcast.

Beyond Payments For High-Risk Industries

Today, most merchants looking to sell a product or service online can quickly get their payment system live with the help of a modern checkout platform. If the merchant works in a “high-risk” industry like games, sports betting, telehealth, travel, or cannabis, however, it’s more complex. Such industries lack viable out-of-the-box software products that help with payment-adjacent issues such as identity management (for games companies), payment reconciliation (for telehealth businesses), and logistics compliance (for alcohol and cannabis businesses). While there are a few big payment-acceptance incumbents to specifically serve some of these industries, there’s now an opportunity to couple payments with a vertical-specific software layer to offer better compliance, wallets, tools for identity management and fraud detection, reconciliation, and more.

The 16 Commandments of Raising Equity in a Challenging Market

Between inflation, rising interest rates, geopolitical tensions, and growing recession concerns, 2022 was a year of reckoning for both public and private markets. Since the beginning of 2022, the tech-heavy Nasdaq Composite has declined 23% (versus the S&P 500’s 14% decline) and global venture funding reached a thirteen-quarter low in Q1 ’23. Further dampening investor confidence, the failure of several long-standing institutions serving the startup ecosystem, such as Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, and First Republic Bank, sent shockwaves through capital markets and the broader financial services industry. Today’s market represents a radically different fundraising climate—one not seen in nearly 15 years. Many founders find themselves in uncharted territory as concerns linger around the overall health of the fundraising environment, from venture capital to growth equity.