- What Founders Should Know About Raising Debt

- The Real Cost of Medical Debt: Why Upcoming CFPB-Driven Changes to Medical Debt Reporting Could Harm Consumers

- Finding the Leading Wealth Management Offerings of Tomorrow

- Opportunities Abound for Fintechs Solving Unmet Needs in Ecommerce

- How JPMorgan’s Global Shares Acquisition Fits into the Trend of Banks Looking to Bolster Their Traditional Services Businesses

- What Apple’s Acquisition of Credit Kudos Signals For Its Fintech Future

- Recent a16z fintech investments

This first appeared in the monthly a16z fintech newsletter. Subscribe to stay on top of the latest fintech news.

What Founders Should Know About Raising Debt

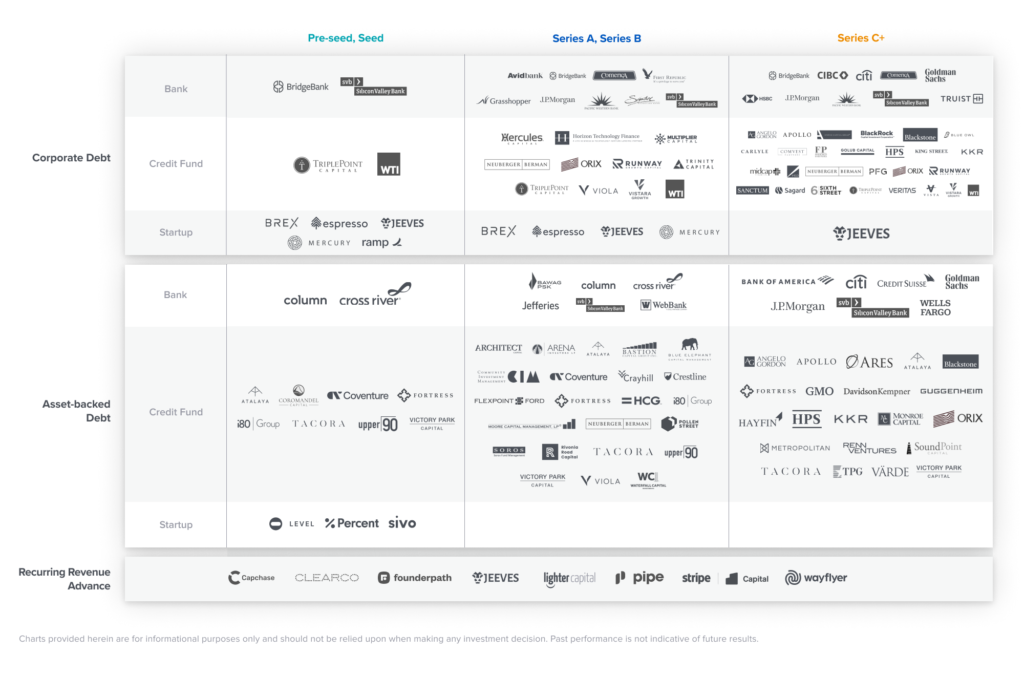

Melissa WasserFor fintech lending companies, capital is akin to inventory, since they effectively sell capital to customers to generate revenue. The more you grow your originations ($ volume of loans created), the more revenue you generate in the form of interest and fees. Since loan origination is the key revenue driver, new fintech lenders typically need to raise more capital earlier. We’ve seen a recent spike in new fintech companies looking to raise debt in order to fund new financial products while minimizing dilution. Traditional venture debt facilities, such as term loans, aren’t optimized for the scaling needs of fintechs, and we’re seeing more and more fintechs turn to asset-backed debt, such as warehouse facilities—and more and more lenders.

With so many lenders to choose from across so many different types of debt facilities, who should you raise from? What type of debt should you raise and how much? What terms are reasonable?

We explore common questions, different types of debt, and the lender ecosystem in our guide to raising debt.

More from a16z this month: Justin Kahl and David George recently published a framework for navigating down markets, and in the spirit of every company becoming a fintech company, Andrew Chen, Jonathan Lai, and James Gwertzman explain why they’ve launched a new fund dedicated to building the future of the games industry. Plus, Marc Andrusko, David Haber, Daisy Wolf, and Julie Yoo on opportunities in healthcare fintech.

Read: A Framework for Navigating Down Markets >>

The Real Cost of Medical Debt: Why Upcoming CFPB-Driven Changes to Medical Debt Reporting Could Harm Consumers

Anish Acharya, Marc AndruskoThe three major credit bureaus announced earlier this year that they will be dropping most medical debt from credit reports. Both paid and unpaid collections under $500 will be dropped in the coming year, and the reporting requirements around such debt will be made more favorable to consumers (i.e., adding a one-year hold period before furnishing such data). At first glance this looks like a clear win-win; we know there is a high degree of inaccuracy in medical debt reporting that harms consumers (through decreased access and increased cost of credit), lenders (who make less money by being unnecessarily restrictive in underwriting), and bureaus (whose product is accurate data). And we know that most collections (by count) are for small-dollar medical debt, making the reach of the problem significant (43 million individuals). What’s not to like?

Unfortunately the campaign driven by the CFPB (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau) to change medical debt reporting will do the very opposite of what was intended. It’s likely to decrease accuracy and increase the cost of credit for non-prime U.S. consumers (generally the middle class, the young, and the working poor). By reading the primary sources published by the CFPB and their claims, we can better understand how and why.

The most recent study of medical debt by the CFPB states the challenges it sees with current reporting practices and identifies disparate impact and diminished predictive value as the primary consumer harms they wish to see rectified by industry. Solving for the former can be a philosophical question of equality of process vs. equality of outcome, while solving for the latter is very much in the interest of all parties (consumers, lenders, and bureaus).

We focus our attention on the latter, the source of which is this CFPB study from 2014, which is cited to back up the claim that “Medical debt collections are less predictive of future payment problems than other debt collections are [1].” The cited study comes to two conclusions: that both paid medical collections are less predictive of future defaults and that all medical collections taken together (paid and unpaid) are less predictive of future defaults than non-medical ones. However, the very same study also states that “[For consumers with mostly unpaid medical debt] The new account performance measure yields predominantly negative score differentials, suggesting that the scores of these consumers were higher than they should have been given their subsequent performance. That is, they appear to have been under-penalized” [2] (emphasis added).

So we know from the CFPB’s own data that unpaid medical collections appear to “under-penalize” consumers while paid medical collections appear to “over-penalize” consumers. Thus the logical conclusion is that accuracy could be improved by removing only paid medical collections from reports or changing the way that FICO and Vantage scoring models count these collections. Credit scores that include unpaid medical collections predict the probability of future delinquency better than those that don’t, and should therefore remain a part of credit reports and FICO/Vantage scores. Bureau changes to remove both paid and unpaid medical collections are likely to reduce accuracy, thereby increasing the cost of debt for non-prime consumers (through higher interest rates to compensate for higher loss rates that are harder to predict). The changes could also potentially increase the costs of care (e.g., a lot of medical bills may suddenly add up to $501, as providers become aware of the new threshold and look to bump prices to ensure patients have an incentive to pay on time).

Finally, it’s worth mentioning that we already have existing market forces and incentives that address inaccuracies in credit reporting, given the potential harm to consumers, lenders, and bureaus. For example, changes in the most recent FICO model already discount paid medical collections. In addition, the existing bureau dispute process tends to give the benefit of the doubt to consumers. And finally, lenders rarely use FICO scores for actual underwriting (it’s more often used for hard cuts and securitizations), and they have an existing incentive to lend to as many creditworthy people as possible.

With all these dynamics in mind, we fear that while well-intentioned, the newly proposed changes to remove certain unpaid medical debt from credit reports could be wholly negative for consumers. Our suggestion would be to proceed with removing paid medical debts, and reconsider how to treat unpaid ones, as the unintended consequences of higher interest rates and healthcare prices could end up having the opposite of the desired effect.

Finding the Leading Wealth Management Offerings of Tomorrow

Joe Schmidt, Anish AcharyaAt its core, wealth management is fairly straightforward: an advisor helps a customer optimize their tax and investment strategies to maximize wealth creation and preservation. But while this premise may seem simple, its execution is growing increasingly complex, especially as wealth management customers and their needs change. New customer classes like millennials have started to amass wealth through emerging alternative asset classes like crypto and collectibles and through intricate equity structures like options and RSUs (restricted stock units). Wealth management customers of all ages also increasingly manage their finances and investments through digitally native startups, such as Robinhood and Titan, rather than traditional institutions.

As the customer changes, so does the playbook for wealth management, making this an interesting time to build in the space. A wave of new investing tools have created market opportunities for new wealth management solutions for both consumers and independent advisors. In this post, we identify some of the most promising initial wedges—narrow product offerings that allow a foothold in the market—for consumer and advisor-driven wealth management startups.

Consumer Wealth Management Strategies of the Future

Historically, the wealth management industry has been an asset-accumulation game where players wage war to build the largest asset base possible. The playbook has been defined by asset accumulation, usually a cost center, and then asset deployment, usually a profit center. Vanguard, for instance, offered rock-bottom prices for accumulation (cost), and then monetized off small fees on their mutual funds (profit). At the high end of the market, Goldman’s private banking services (cost) created one of the most notable status symbols in financial services, while their proprietary funds and management fees (profit) created the profitable wealth management empire they have today.

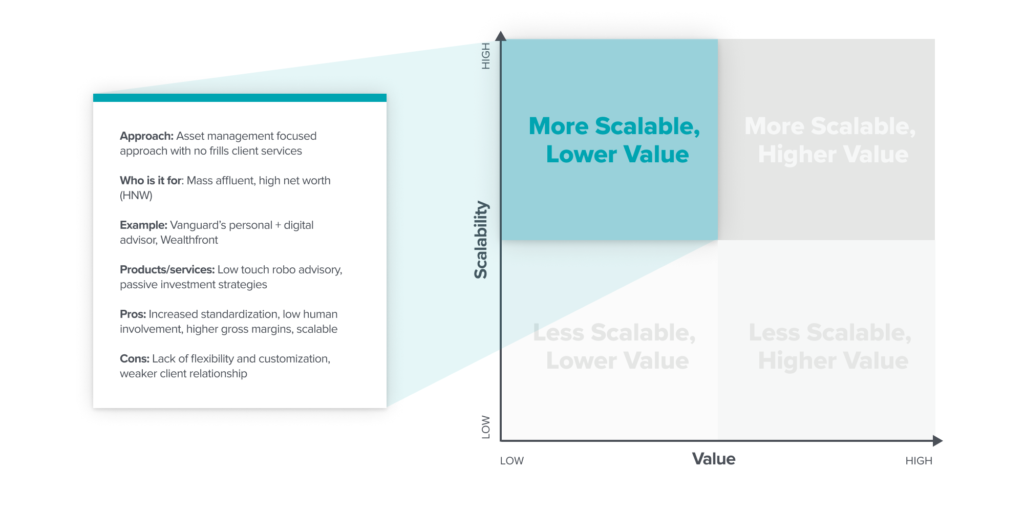

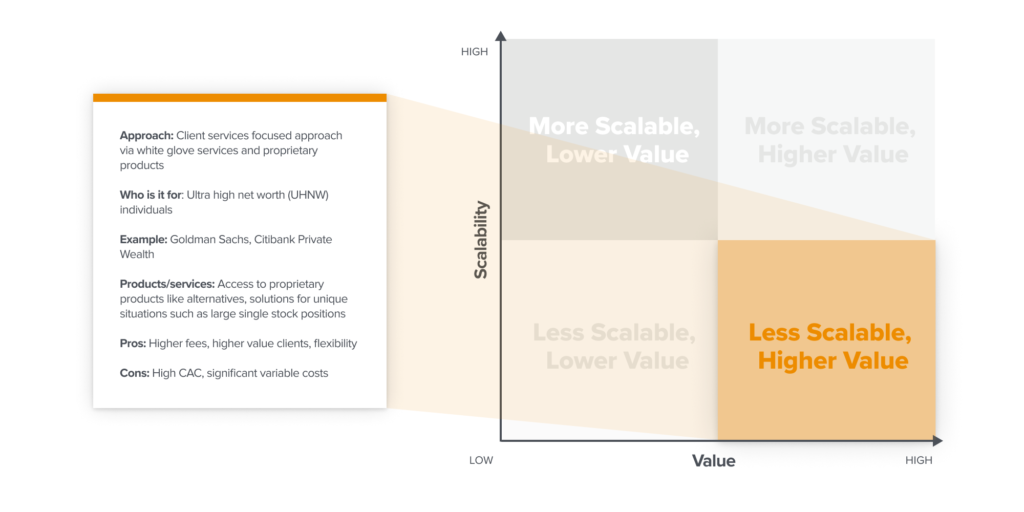

The difference between Vanguard’s approach and Goldman’s highlights two traditional wealth management business strategies: offering scalable but lower-value services (Vanguard), and offering less-scalable, but higher-value services (Goldman). The trickiest part for any wealth management business is figuring out how to make the unit economics work, while waiting for increasing returns to scale. For example, Vanguard needed ~20 years (from its establishment in 1974 to 1994) to reach $100B+ in assets under management (AUM). Meanwhile, for companies offering less scalable, but higher-value services, the challenge is often how to reliably hire high-quality people to deliver high-value service experiences.

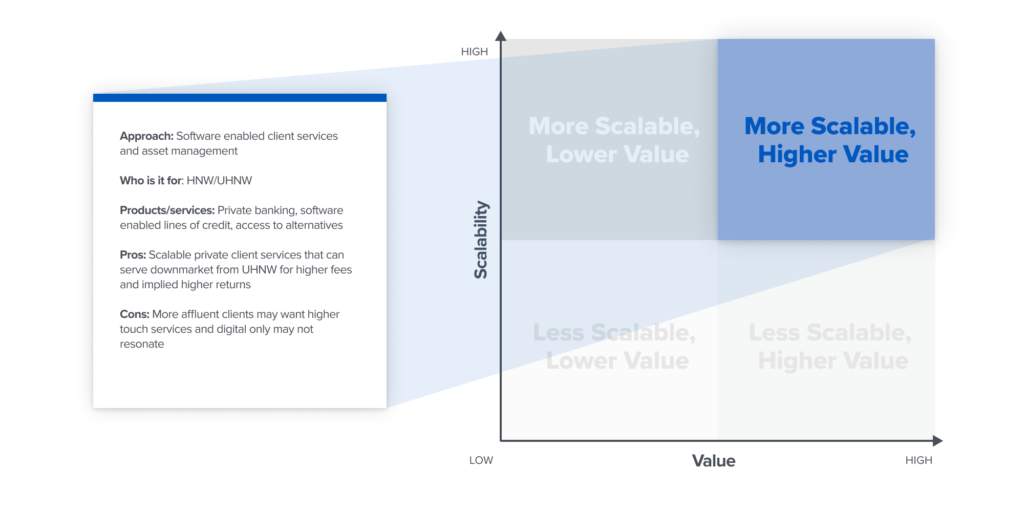

We’re excited for technology to solve this problem and perhaps unlock a third bucket of scalable, high-value services. For example, we’re seeing startup activity in some hard-to-crack areas, like lending, estate planning, alternative assets, and tax—all areas where traditional wealth management providers have needed to hire linearly to scale their offerings.

We believe the best startups that exemplify this new potential high-scale, high-value bucket are those whose offerings have urgency and significance. In this case, by urgency, we mean a startup’s product is so enticing that after a consumer encounters the product—through, for example, an ad—they immediately want to sign up. By significance, we mean that when a customer signs up for the product, they reap rewards that don’t mirror traditional solutions.

For example, Chime, the neobank that offers no-fee banking, created urgency for its customers to sign up through its get-paid-early program, and then added significance by eliminating overdraft and other hidden fees commonly charged by incumbents.

The Rise of Breakaway Advisors

Beyond consumer-side opportunities, there are additional opportunities to provide products to a new class of wealth advisors: independent breakaway advisors. As technology improves and governments propose new fintech regulations, many advisors that historically sat on Wall Street now run their own independent businesses and rely on a robust technology ecosystem to help them meet their clients’ needs.

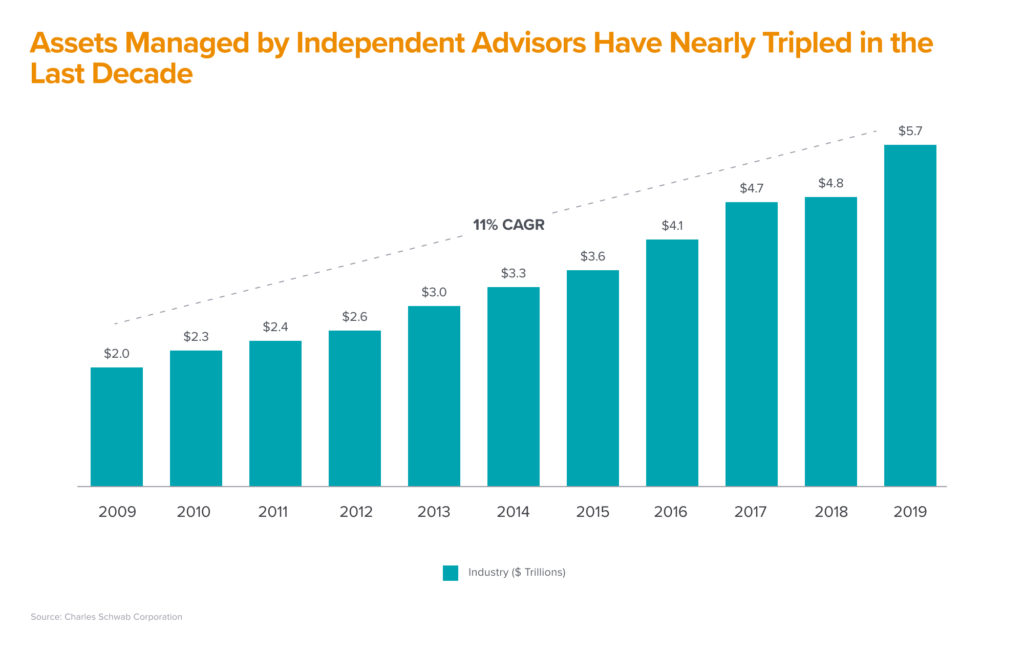

This trend, colloquially described as the rise of breakaway advisors, is perhaps the most important trend over the past decade in wealth management. This shift has only accelerated over the past decade, as assets managed by independent advisors have grown nearly 300% (see below).

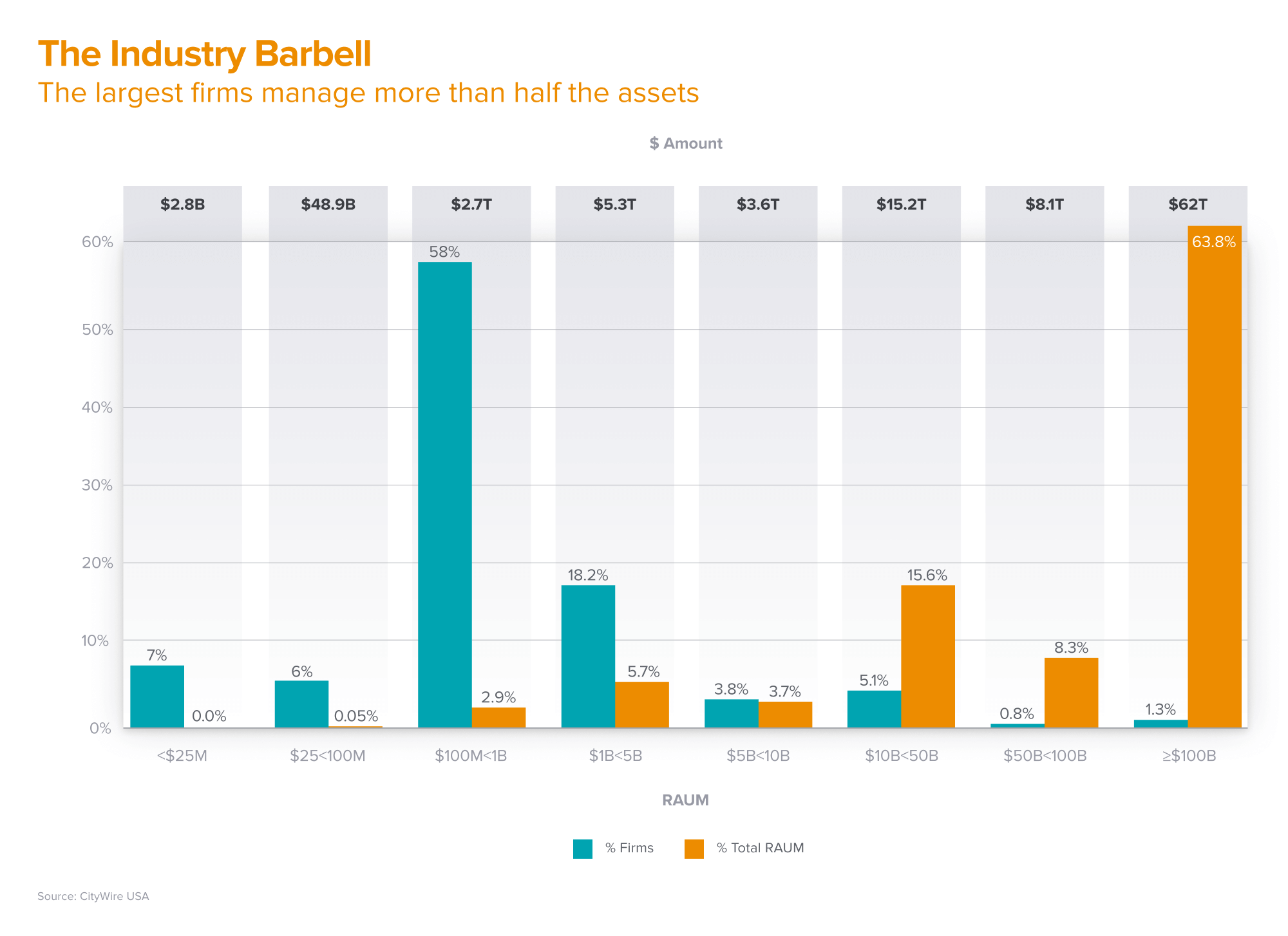

That being said, many independent advisors are part of a larger RIA or broker-dealer, and the majority of assets still reside either within a large independent or wirehouse today. In other words, despite the rise of breakaway advisors, consolidation at the top of the market hasn’t changed.

However, we’re still in the early days of this shift, and there are a few opportunities to provide breakaway advisors with the tools they need to independently manage more wealth. Specifically, we are looking at tools that address compliance, alternatives, and aggregation models, all of which can help independent advisors operate as solopreneurs.

Vertical Solutions for Compliance

Today’s laws governing wealth management date back to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and the Advisers Act of 1940, which named and created standards for investment advisors (e.g., fiduciary responsibility and standard of care). These regulations have been modified several times, most recently in 2019 with Regulation Best Interest, or Reg BI, enhancements to legal requirements and mandated disclosures.

These new regulations create an interesting wedge for businesses to be built around compliance and disclosure workflows. One area we’re following is the proposal process, or where the sale is actually made. Capturing data here can lead to simpler tracking of what products are being presented, which creates the evidence needed to comply with Reg BI and helps drive more sales for the advisor. CapIntel in Canada and Stratifi in the U.S. are two examples of businesses we’ve seen building in this space.

Vertical Solutions for Alternatives

Although consumers, largely driven by interest in crypto and web3, have flooded into alternatives over the past several years, there are only a few services that streamline the experience of accessing these types of investments through a financial advisor. Issues can arise across the entire stack, from sourcing and evaluating new investment opportunities, coordinating capital calls, and entering into new alt positions, to tracking and reporting on these investments. In many cases these types of positions can also complicate tax and estate planning, creating an even bigger issue—and opportunity for startups.

In response, many larger advisors are hiring additional operations people to help manage this process, while smaller advisors aren’t offering these services at all. Offering access to this type of investment opportunity will be table stakes for advisors in the future, making this a unique moment in time to build solutions around this need.

Reimagining Aggregation

A variety of new aggregation models lets breakaway advisors do what they do best—client interaction—while digitizing the back-office solutions required to run an independent advisory firm. Some of these new aggregation players innovate by improving how fast advisors are paid for products, which can be a strong wedge to sell into a cash-constrained small advisory firm.

These aggregation layers often participate in the fee structure of the advisors rolling up to them, and there are interesting volume-based dynamics that can drive increasing returns to scale. Increased volume can yield increased compensation, and independent advisors can, in some cases, earn more as a part of the collective than as a solo operator. Some firms, like Dynasty Financial and Crump, have historically run variations of this playbook and built great businesses. Others, such as Farther and Savvy, are reimagining what a business-in-a-box for an independent advisor might look like, while Signal Advisors is changing the dynamics around cash flow and access to retirement products.

As wealth management continues to grow and evolve, we’re excited to meet and partner with teams that are building new, digitally native consumer experiences, as well as solutions that serve traditional financial advisors.

Opportunities Abound for Fintechs Solving Unmet Needs in Ecommerce

Sumeet SinghFintech and ecommerce have been interlinked for the past two decades, and both have benefited from the same tailwinds that have furthered mobile and digital-first experiences. Not only have companies like PayPal, Stripe, Affirm, Checkout.com, Klarna, and Sift benefited from this ecommerce symbiosis, but they are all now household names. However, while companies have largely solved for early challenges like payment acceptance and fraud, we believe there remains a huge opportunity for fintech startups to identify and provide solutions across other segments of the product journey and service digital merchants’ still unmet needs.

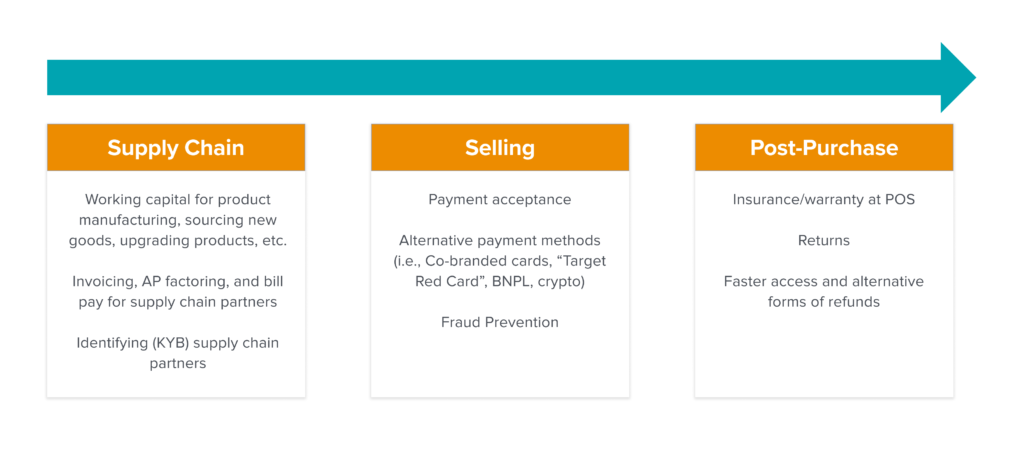

Currently, a merchant’s product journey involves three pillars: 1) sourcing and/or manufacturing goods (“supply chain”), 2) selling those goods (“selling”), and 3) engaging with customers after their purchase (“post-purchase”). Within these three pillars, a handful of fintech companies offer solutions to different pieces of the larger product journey puzzle, be it working capital (via ClearCo or Wayflyer); payment acceptance (via Stripe, Adyen, or Checkout); alternative consumer financing (via Affirm, Klarna, or Afterpay); fraud prevention (via Sift or Forter); or insurance/warranty (via Extend or Clyde).

In the supply chain leg of the product journey, we believe there is a massive opportunity to help ecommerce-specific merchants with accounts payable, invoice factoring, and bill pay. Today, most merchants normally rely on Bill.com or manual, email-based processes to issue payouts. Merchants must also deal with a cash-flow crunch, as they often have to pay a deposit upfront to their manufacturing partners and do not capture the full revenue potential from that supply for up to 3 months. Companies like Settle and Wayflyer have shown there is massive demand to help with this issue, and companies that can use this wedge to become an operating system for ecommerce merchants will find success. Additionally, as merchants source products from all over the world, they need better global know-your-business (KYB) tools to understand the risk levels of partnering with international entities. While merchants can utilize companies like Middesk for U.S. KYB, there is a clear opportunity for a global provider.

In the selling leg, we believe there is still an open playing field for fintech companies that are enabling consumer-friendly offerings such as “Target Red Cards as a Service.” With programs like these, merchants essentially build a closed-loop relationship with their customers. This simultaneously increases conversions, saves merchants on card network-related fees, and rewards customers.

We also see a major need for fraud-protection services for merchants within the selling leg. While plenty of startups already offer fraud protection services to ecommerce companies, bad actors are continuously evolving as well. New startups that have an edge on capturing the most relevant signals—such as biometric, behavioral, identity, etc.—will continue to thrive. In a related field, merchants also need solutions for payment declines and increasing conversions, which may be a result of perceived non-sufficient funds (NSF) risk or a mismatch in risk tolerance between merchants and issuers. Merchants today do not have sufficient tools to combat these declines, as ~50% of the time, all they receive from issuers is a “do not honor” decline code. To resolve this decline, they must ask customers to call their issuing bank to determine why the transaction was declined—which is clearly a terrible customer experience. All in, $800B of payments were declined by issuers in 2021, which had a debilitating impact on merchants.

On the post-purchase side, there is an opportunity for fintech companies to help merchants build stronger relationships with customers and increase average order value (AOV) and conversion. Merchants can partner with fintech companies to offer embedded insurance/warranty, help customers return products more easily, and also provide faster and alternative access to customer refunds, which still typically take 3-10 business days.

While these fintech opportunities may seem incremental vs. providing a step-function change (such as Stripe giving merchants the ability to accept payments online), the pandemic significantly accelerated ecommerce penetration, providing an opportunity for new startups to emerge tackling the aforementioned gaps along the ecommerce product journey.

What Apple’s Acquisition of Credit Kudos Signals For Its Fintech Future

Seema Amble, Marc AndruskoEarlier this year, Apple announced its intent to acquire UK-based Credit Kudos. It’s a deal we think makes a lot of sense for the future, as well as right now, given the rapidly evolving macro landscape.

Credit Kudos pulls consumer banking data such as account balances and transaction information for its customers. Using this data, Credit Kudos creates consumer scores and insights to help its customers make underwriting decisions and more. With this acquisition, Apple could be pushing further into providing financial services itself, rather than just serving as the primary technology and distribution partner for other financial institutions.

Apple’s acquisition is only one of several recent open banking acquisitions. Visa, for example, acquired the Swedish fintech Tink in 2021, while Mastercard acquired Finicity in the U.S. in 2020 and Aiia in Europe late last year. While these transactions were conducted for ostensibly different reasons, they were all likely motivated by a desire to expand each card network’s core payment rails to include bank-to-bank payments.

The Credit Kudos deal goes one step further. The company currently provides a layer of insights on top of transaction data like predictive income, as well as scoring attributes like consistency and longevity of income. This banking data—as well as Credit Kudos’ underwriting insights—can be strategic and valuable for Apple for a number of reasons. First, this data enables cash-flow based underwriting. Rather than relying on credit bureau data, which looks at repayment history and calculates a score, cash-flow data provides direct access into a consumer’s transaction and lending history (with their consent). An individual’s credit score can take weeks or months to update, and scoring methodology can take years to incorporate new types of data points (e.g., BNPL or rent), as we’ve discussed before. Real-time underwriting decreases reliance on a middle layer and potentially benefits consumers with lower credit scores, as this group is making credit progress, but may not see their improvements immediately reflected in their lagging credit scores.

Apple also isn’t a bank or lender which might more obviously incorporate this data into its existing risk underwriting, or a card network looking to extend its rails. As Apple pushes further into financial products with Apple Pay, the Apple Card, Tap to Pay, and more, the acquisition of Credit Kudos enables the company to take more control of the underwriting (and therefore the economics) over time. Previously, Apple relied on its banking partners to lead the underwriting process; currently, Goldman Sachs still manages the risk selection for the Apple Card.

Long term, Apple and presumably other tech companies are probably better equipped than more traditional lenders to move quickly and innovate in their use of data and lending models. That said, Apple has yet to own the balance sheet and capital risk (which would require banking licenses)—but over time, that might be its ambition. In fact, leaked rumors of “Project Breakout” would suggest just that, and AppleInsider reported that Apple is actively developing new technology and infrastructure to bring future financial services offerings, including payment processing, risk assessment, fraud analysis, and credit checks, in-house. One can certainly imagine a world in which Apple leverages the scores it receives from Credit Kudos to facilitate its own BNPL loans (for, say, the iPhone upgrade program) instead of relying on partners like Citizens Bank for balance sheet and underwriting.

As it turns out, all of this is incredibly timely. While Apple and Credit Kudos have presumably been working on this transaction for many months, the consumer credit picture in the U.S. is materially changing today. According to Federal Reserve data, revolving credit (credit card balances resulting from actually borrowing money) increased at an annual rate of 21.4% in March, while non-revolving credit (balances that will be repaid on time) increased at an annual rate of 6.1%. This dramatic uptick in revolving credit, plus the rapid and widespread adoption of BNPL loans (many of which don’t involve fulsome underwriting), could very well mean that the average consumer’s credit picture requires more improvement than they might think.

In a historic bull market, where consumers have the luxury of focusing more on high-risk, high-reward investments like equities and crypto, credit may not have been top of mind for them. But in this new macro environment—where inflation is >8%, rates are rising, and the stock market is correcting itself—consumers may well find themselves in need of credit on a rainy day. If lenders rely on credit scores in a vacuum, these consumers may be out of luck. But with the Credit Kudos acquisition, Apple will be supremely well positioned to ensure its customers can continue to finance purchases of the electronics they use to run their daily lives. Open banking data can help ensure the customer’s full financial picture is being considered when they apply to upgrade their iPhone or finance a new laptop.