It’s a Silicon Valley truism that product-market fit matters most for a startup. A founder’s ability to achieve that elusive goal is what separates the mega-donkey-deca-unicorn success stories from the vast majority of startups that either die quick and sudden deaths or peter out slowly, unnoticed.

I’ve observed, both as a founder and in our conversations with startups, that finding product market fit is frustratingly vague: Everyone tells you you need it, but offer only hazy generalities on how to get there. Most guidance boils down to “listen to your users.” Good advice, but it still leaves open the question of how to get those critical first users—to say nothing of the people or capital needed to iterate.

The fact is that people need a different motivation to try something new, something that connects with them emotionally rather than functionally. It’s a seemingly simple idea can create powerful business advantages, a concept I call product zeitgeist fit (PZF): when a product resonates with the mood of the times. It’s the thing that makes users and employees want you to win. It’s also the thing that helps other stakeholders—media and trend watchers, big companies, other builders—spot the next big thing.

Download the full deck for “The Allure of Product Zeitgeist Fit” here.

Product zeitgeist fit: How does it work?

Harnessing and cultivating the zeitgeist buys you the time and energy you need to gain support on your way to product-market fit. Product zeitgeist fit helps answer the age-old question—beyond tech platform shifts and other factors—of why some things, especially in consumer tech, work and others just don’t. It helps explain why something that seems really weird and awkward, like letting a total stranger sleep in your house, can become a global phenomenon, and why something that seems really clever, like a private social network, just don’t… yet. And it can help explain why a concept like online pet food delivery can blow up in a bad way in one era, then blow up in a really good way 15 years later.

When you have PZF, the product resonates with users not because it’s better, but because it feels extremely culturally relevant at that particular moment in time for a particular group of people. Users may or may not love your product, but for some reason they want it to win. Maybe because they hate the competitor with the “better” product. Maybe it’s because the current product appeals to a particular value or aspiration. Regardless of what drives it, it’s an unfair advantage that can separate winners from the also-rans.

Most startups die not because they can’t get their tech to work or because their competition out-executes them. The death of most startups is indifference. Put simply, most companies fail to launch because no one cares: not users, not employees, not investors, and certainly not the media. It’s death by a thousand shrugs.

When you’re riding the zeitgeist, you’re able to catalyze energy from the four forces that can change the trajectory of a company:

- Early adopters

- Early employees

- Angel and seed investors

- The media and other analysts that cover these frontier ideas

When those four groups care about what you’re doing, impossible things suddenly become possible. It gives you the momentum to get started.

The death of most startups is indifference. Put simply, most companies fail to launch because no one cares: not users, not employees, not investors, and certainly not the media. It's death by a thousand shrugs.I want to be clear that finding PZF isn’t the end of the story, it’s the beginning of it. You still need to work your way to product market fit, a functional use case and mainstream adoption. But finding PZF is like getting a thousand extra chances as you weave your way to product market fit.

There are several recent examples that illustrate how product zeitgeist fit plays out, beyond a mere philosophy.

Crypto

At the height of the financial crisis in 2009, anger at Wall Street and big banks spiked. Declining trust in traditional, centralized institutions was palpable. As the decade went on, there was growing momentum to do something about those large platforms and companies that adversely affect our experiences and societies.

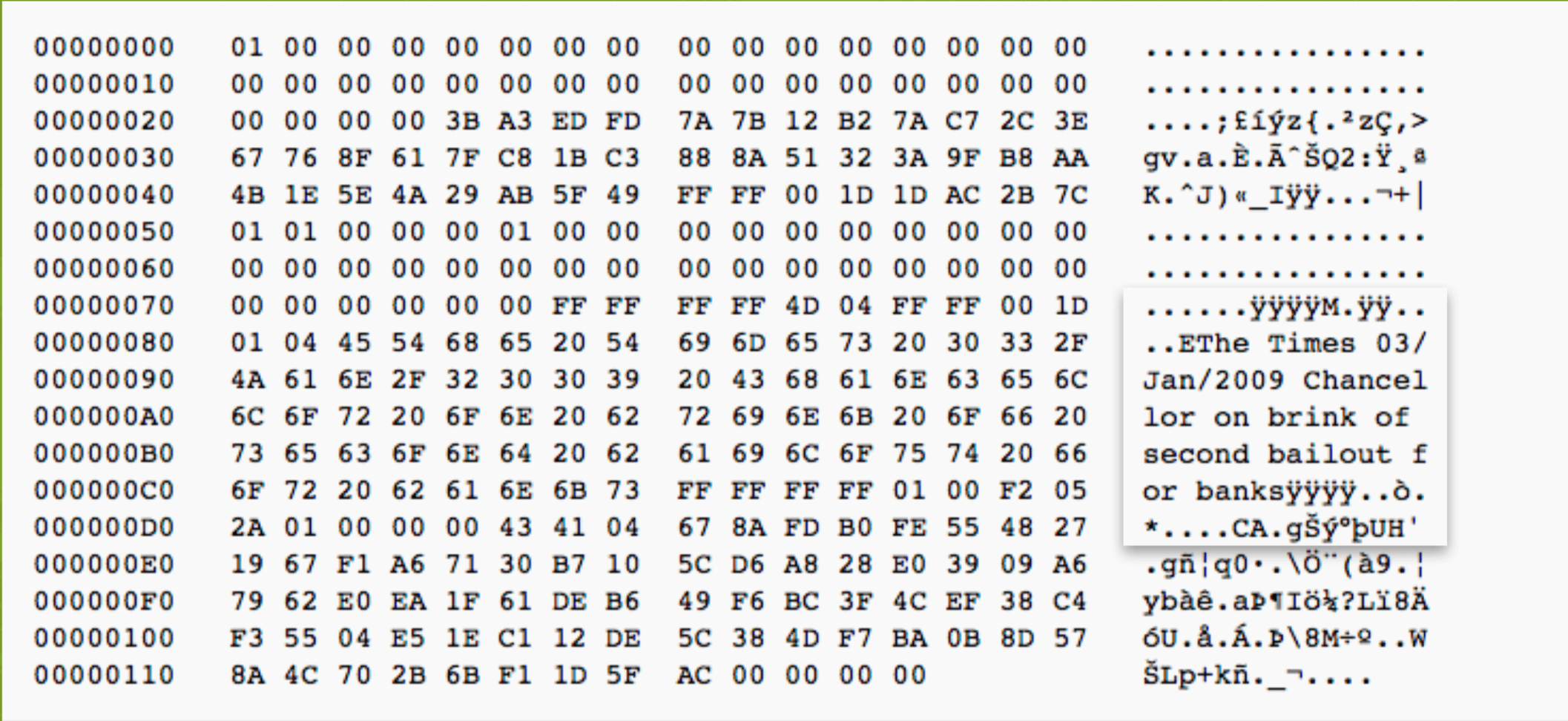

Those ideas—frustration with Wall Street, mistrust of institutions, and, for lack of a better term, FAANGer— connected with what the crypto community was building. It gave crypto the energy, excitement, and funding to get the flywheel spinning. We’ve had a lot of attempts at internet money before, but it was only in 2009 (when the Bitcoin whitepaper was published) that we really found that spark. If you don’t believe me, look at the Genesis block of Bitcoin, the first link in the chain.

In the comments section, Satoshi embedded a message about the financial bailouts. Though a precise motivation is unknown, the ethos around mismanagement of the traditional financial system fueled a lot of the enthusiasm around crypto in the early years.

But here’s the thing about crypto: for those in the mainstream, it’s still not that easy to use. Despite that, people are still using it, building on it, investing in it, and writing about it, allowing it to hold product zeitgeist fit as it moves toward product market fit.

Clean meat

Like the concept of internet money, the idea of a veggie burger isn’t new, but it’s something that’s found new life in the last few years as it resonated with the zeitgeist.We’ve seen an increased urgency around climate change in recent years, which has inevitably fueled a conversation about the impact of the Western diet. At the same time, the media has brought a host of moral and ethical issues around industrial farming to the fore. Those two ideas—industrial farming and climate change—have given companies producing clean meat the boost they needed to make the idea take off this time.

But has anybody actually tried one of these burgers? Some are okay; some are (subjectively) disgusting; and there are open questions about the health benefits of them. Despite that, people are still lining up to buy them, talented scientists are still working on it, investors are still funding it, and big companies are still trying to partner with them. It’s not better than meat—yet—but it’s got a great chance to get there thanks to product zeitgeist fit.

Income Share Agreements (ISAs)

Income share agreements are a financial instrument in which someone (usually a student), gets something (usually tuition), in exchange for a share of his or her future income. Like internet money and veggie burgers, this idea isn’t new, but it’s something that seems to have found its moment.

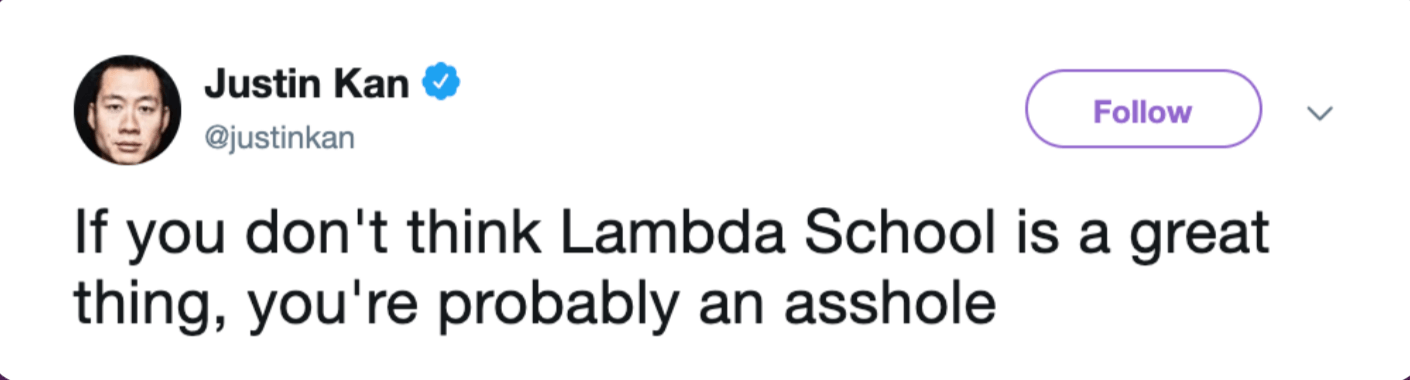

The explosion in student debt in our educational system is dominating conversations across the news, social media, and politics. At the same time, trust in traditional academic institutions is declining, an attitude that becomes supercharged with every new admissions scandal, replication crisis, and marketing scandal. The two ideas—of distrust of academic institutions and of overwhelming student debt—have given ISAs and the companies and schools using them the boost they needed to really get going this time.

Of course, ISAs still need to navigate a complicated web of behavior change, consumer protections, regulation, and returns to investors. But despite that talented people are still working on it, talking about it, and trying to make it work. It’s unclear whether ISAs have product market fit just yet, but thanks to PZF they’ve got an incredible chance to get there this time.

These are just three examples; there are all kinds of things that are bubbling up in the zeitgeist today, whether it’s privacy products, frustration with the attention economy, the Marie Kondo-ification of everything including clothes, or the desire for a new social network (of which there have been many attempts lately). And the founders that are building on top of these ideas today all have a massive advantage today. That’s the thing about the zeitgeist: Just because something like a private social network didn’t work eight years ago, that doesn’t mean it couldn’t work today.

How to spot product zeitgeist fit

How do you identify something as ephemeral as the product zeitgeist fit? Here are four tests to spot it in the wild.

- “Nerd Heat”: Coined by my partner Chris Dixon, this is when the most talented, hardest working, and most in-demand people—the product managers, engineers, and data scientists—are so intrigued by a product that they’re working on it, excited by it, and trying to make it a thing.here’s a good chance that they’ll eventually make it happen, moving it beyond the fringes to the mainstream.

- The “Despite Test”: When people are using a product despite the fact that it’s not the best thing out there, or, in some cases, that it’s straight-up terrible (see examples above), it’s a great sign. It shows that the product has a line into something emotional, not solely functional. Wanted, not just needed.

- The “T-shirt Test”: If people with no connection to the company are wearing their t-shirts or putting their stickers on their laptops or wearing their socks, that desire to associate with the idea indicates as much a movement as a product.

- The “Eyebrow Test”: In the early days, things that have product zeitgeist fit often feel misunderstood or controversial. At first blush, the conceit may even raise a few eyebrows. But to the people who have been working on those products, they’re so clearly elegant, if temporarily imperfect, solutions to big and important problems that they seem almost obvious once they recognize it.

Product zeitgeist fit favors the upstarts

When observing what actually gets into the zeitgeist (and what doesn’t), I’ve noticed three trends that have important implications for innovation.

These things tend to be generational; they’re reactionary; and they’re usually organized around a really compelling villain. Because we always seem to react against the unintended consequences, excesses, and blind spots of the previous generation, the zeitgeist is constantly changing. That means there’s always going to be an opening for innovators and disruptors, especially in consumer tech. That’s why, despite all the talk of unbeatable incumbents and ossification, I’m optimistic about the next generation of technology companies.

Founders: Find something that is both important to you and resonates with a group of people at this particular moment in time. In the early days you’ll need to frame your story—to recruits, to partners, to investors, and to the entire outside world—along those lines. Talk about why your company matters, not just what it does. Make sure your product remains authentic and product decisions are connected with the mission. Finally, make sure the people you hire are as connected with these ideas as you are. Give everyone a reason to cheer for you. Because if you can get to product zeitgeist fit, you’ve got an unquestionable advantage in getting to product market fit.

And if you’re just trying to figure out what the future looks like, not just build it, look for the things that are broken and terrible but that people still really care about. Look for the four tests: the raised eyebrows, the T-shirts, the nerd heat, and the people that are still using a product, despite its shortcomings. Look for the things that are reacting against the previous generation and resonating with the mood of the times. Ultimately, that’s where the future lies: at product zeitgeist fit.

Download the full deck for “The Allure of Product Zeitgeist Fit” here.