Marc Andreessen is able to explain himself so well that I should have less commentary to add to the quotations in this post than usual. But where is the fun in that? My primary task with this blog post has been assembling the quotations and placing them in an order which flows well, since understanding the earlier topics helps the reader understand ideas which come later in the list…

#1 “The key characteristic of venture capital is that returns are a power-law distribution. So, the basic math component is that there are about 4,000 startups a year that are founded in the technology industry which would like to raise venture capital and we can invest in about 20.” “We see about 3,000 inbound referred opportunities per year we narrow that down to a couple hundred that are taken particularly seriously… There are about 200 of these startups a year that are fundable by top VCs. … about 15 of those will generate 95% of all the economic returns … even the top VCs write off half their deals.”

I have done several posts on the fundamental forces which create power laws in venture capital. If you don’t understand the forces which create power laws in venture capital, you don’t truly understand venture capital. Power laws don’t happen by accident. There are always factors feeding back on themselves when something like investing results are reflected in a power law, and venture capital is no exception.

Why power laws? To understand venture capital as well as many of the phenomena impacting individuals, companies and the global economy right now, you must understand cumulative advantage and its inverse cumulative disadvantage.

Robert Merton has described cumulative advantage in this way: “exceptional performance … attracts new resources as well as rewards that facilitate continued high performance [repeat].” Additional ways that people use to describe this phenomenon include the Matthew effect, virtuous circles, and the rich get richer.

Another important factor known as Path Dependence is used to describe at least three phenomenon: increasing returns, self-reinforcement, and positive feedback. Of course, it also the case in that failure can create negative feedback loops and vicious cycles which can make the poor get poorer. As was noted above, cumulative advantage and path dependence are operating and are self-reinforcing at every scale (e.g., individuals, startups, established businesses, communities, regions, nations and the global economy).

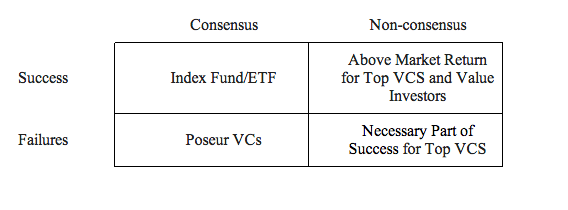

#2 “We think you can draw a 2×2 matrix for venture capital. …And on one axis you could say, consensus versus non-consensus. And on the other axis you can say, successful or failure. And of course, you make all your money on successful and non-consensus. … it’s very hard to make money on successful and consensus. Because if something is already consensus then money will have already flooded in and the profit opportunity is gone. And so by definition in venture capital, if you are doing it right, you are continuously investing in things that are non-consensus at the time of investment. And let me translate ‘non-consensus’: in sort of practical terms, it translates to crazy. You are investing in things that look like they are just nuts.”

“The entire art of venture capital in our view is the big breakthrough for ideas. The nature of the big idea is that they are not that predictable.”

“Most of the big breakthrough technologies/companies seem crazy at first: PCs, the internet, Bitcoin, Airbnb, Uber, 140 characters.. It has to be a radical product. It has to be something where, when people look at it, at first they say, ‘I don’t get it, I don’t understand it. I think it’s too weird, I think it’s too unusual.’”

This set of quotations reminds me of Howard Marks, who has said: “To achieve superior investment results, your insight into value has to be superior. Thus you must learn things others don’t, see things differently or do a better job of analyzing them — ideally all three.”

The power laws in venture capital virtually guarantee that the poseur venture capitalist who follows the crowd can never make up for all their losers, since they will not get the one or two tape measure home runs required to generate returns that limited partners demand.

What is perfectly advisable for the ordinary investor (“be the market”) spells doom for the venture capitalist because venture capital returns reflect the power law noted above. It is only in the non-consensus quadrants that optionality will be mis-priced and bargains found. Buying optionality is not enough to achieve success as a venture capitalist; it must be mis-priced. Paying too much of any asset including optionality is not a solvable problem. The matrix Marc Andreessen describes above, with an example in each quadrant, looks like this:

#3 “You want to have as much ‘prepared mind’ as you possibly can. And learn as much as you can about as many things, as much as you can. You want to enter as close as you can to a zen-like blank slate of perfect humility at the beginning of the meeting saying ‘teach me’ … We try really hard to be educated by the best entrepreneurs.”

This set of quotations from Marc Andreessen reminds me of a famous quote from Shunru Suzuki: “If your mind is empty, it is always ready for anything, it is open to everything. In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s mind there are few.”

If you go into a meeting with a startup thinking you know everything, you will learn nothing. Similarly, if you think you can predict everything you will fail as a venture capitalist. Of course, not only must the idea of the investor be non-consensus it must also be right.

Most things that seem nuts in fact are nuts. But every once in a while what seems nuts is one of the 15 ideas each year that 95% of financial returns in venture capital.

#4 “You want to tilt into the really radical ideas… but by their nature you can’t predict what they will be.” “There will be certain points of time when everything collides together and reaches critical mass around a new concept or a new thing that ends up being hugely relevant to a high percentage of people or businesses. But it’s really really hard to predict those. I don’t believe anyone can.”

This set of quotes describes the best way to deal with complex adaptive systems — rather than trying to predict the unpredictable, it is best to purchase a portfolio composed of mis-priced optionality.

Warren Buffett describes a portfolio of bets with optionality in this way in his 1993 Chairman’s letter: “You may consciously purchase a risky investment — one that indeed has a significant possibility of causing loss or injury — if you believe that your gain, weighted for probabilities, considerably exceeds your loss, comparably weighted, and if you can commit to a number of similar, but unrelated opportunities.”

Marc Andreessen describes his firm’s approach as being similar to Benchmark Capital and Arthur Rock (i.e., focus on big breakthrough ideas), which is unlike other venture firms that have a process where they try to create value-chain maps of where markets/the industry is going.

#5 Venture capitalists “spend a lot of time talking about markets and technology…. and we have lots of opinions. …but the decision should be around people…. about 90% of the decision [is people].”… “We are looking for a magic combination of courage and genius .… Courage [“not giving up in the face of adversity”] is the one people can learn.”

When you have a team of strong people in a startup, their ability to adapt and innovate gives the company and the investors optionality. Weak teams which can’t adapt to changing environments usually fail.

Identifying the right people is all about pattern recognition.

#6 “An awful lot of successful technology companies ended up being in a slightly different market than they started out in. Microsoft started with programming tools, but came out with an operating system. Oracle started doing contracts for the CIA. AOL started out as an online video gaming network.”

Because the future is not predictable with certainty, companies with optionality in the form of strong teams and research & development capability can pivot into other markets. This can present a problems if you are a venture capitalist which has decided to only invest in one company per category.

There is so much pivoting going on in consumer that some venture capitalists have stopped doing Series A rounds in that category.

#7 “The great saving grace of venture capital is that our money is locked up. The big advantage that we have as a venture capital firm over a hedge fund or a mutual fund is we have a lock up on our money.” “So we invest in these companies with a ten-year outlook.” “And so enterprise can go in and out of fashion four different times, and we can go and invest in one of these companies, and it’s okay, because we can stay the course.”

Another investor who has figured the value of locked up capital from investors is Warren Buffett, who famously closed his partnership and started Berkshire. Unlike a hedge fund, Warren Buffett’s capital is locked up protecting him from people trying to redeem after the panic during a market dip. Bruce Berkowitz: “That is the secret sauce: permanent capital. That is essential. I think that’s the reason Warren Buffett gave up his partnership. You need it, because when push comes to shove, people run.”

The ability of a venture capital firm to have cash in the bank (or at least the ability to call on cash contractually promised by limited partners) allows it to invest through the downturns, which as my post on Michael Moritz explained, can be a very good time to start a company. Andreessen Horowitz itself is proof of that principle. Marc Andreessen has said: “The spring of 2009…. was not a time when investors wanted to hear about a new venture capital fund. In fact, many of the large investors in venture capital and private equity were in a liquidity crisis in their own businesses, including the big university endowments where they were having real trouble meeting their commitments back to their sponsoring organizations… people have told us it was the harshest, most hostile time to raise new capital funding in 40 years. Of course, we are contrarian or perverse, depending on how you look at it, and we said, Well, then it’s probably going to be a very good time to raise venture capital funding.”

#8 “The thing all the venture firms have in common is they did not invest in most of the great successful technology companies.” “The mistakes that we make in a field like venture capital generally aren’t investing in something that turns out not to work. … it’s the big hit that you missed. And so every venture capitalist who had the opportunity to invest in Google and didn’t just feels like an idiot. Every venture capitalist who had the opportunity to invest in Facebook and didn’t feels like an idiot. The challenge in the field is all of the great VCs over the last 50 years, the thing that they all have in common, is they all failed to invest in most of the big winners. And so this again is part of the humility in the profession.”

Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger call this type of mistake an “error of omission” (i.e., what you don’t do can hurt you more than what you actually do).

No one describes this category of mistake better than Charlie Munger: “The most extreme mistakes in Berkshire’s history have been mistakes of omission. We saw it, but didn’t act on it. They’re huge mistakes — we’ve lost billions. And we keep doing it. We’re getting better at it. We never get over it. There are two types of mistakes: 1) doing nothing, what Warren calls “sucking my thumb” and 2) buying with an eyedropper things we should be buying a lot of.”

#9 “With tech — and you see this with a lot of these new entrepreneurs — they’re 25, 30, 35 years old, and they’re working to the limit of their physical capability. And from the outside, these companies look like they’re huge successes. On the inside, when you’re running one of these things, it always feels like you’re on the verge of failure; it always feels like it’s so close to slipping away. And people are quitting and competitors are attacking and the press is writing all these nasty articles about you, and you’re kind of on the ragged edge all the time…“ “The life of any startup can be divided into two parts — before product/market fit (BPMF) and after product/market fit. When you are BPMF, focus obsessively on getting to product/market fit. Do whatever is required to get to product/market fit. Including changing out people, rewriting your product, moving into a different market, telling customers no when you don’t want to, telling customers yes when you don’t want to, raising that fourth round of highly dilutive venture capital — whatever is required.”

Starting a business isn’t easy or for the faint of heart. At the same time there is not business that is easy. Almost every company is less attractive when viewed from the inside than it appears from the outside. My friend Craig McCaw said to me more than once that a ship as viewed from the dock may look pretty with the captain smiling from the upper deck in a resplendent uniform — but under the decks there is inevitably some ugliness associated with the travails of actually running something.

The goal isn’t to be perfect but rather to be a great success.

Working for a startup is something that some people might want to put on a personal bucket list. The reality is that is an amazing life experience, but it is not for everyone. Lots of people talk a good game about wanting to leave a company like Apple for a startup, but when the time comes most don’t actually do it.

As an aside, Marc Andreessen does not buy into the conventional notion among many in Silicon Valley that failure is good. Some failures may be inevitable when you venture out as an entrepreneur or when you take a job in a startup and you may learn from that failure, but in his view the failure itself isn’t good.

#10 “There’s a new generation of entrepreneurs in the Valley who have arrived since 2000, after the dotcom bust. They’re completely fearless.”… “Founders today are very technical, very product centric, and they are building great technology and they just don’t have a clue about sales and marketing…it’s almost like they have an aversion to learning about it.” “Many entrepreneurs who build great products simply don’t have a good distribution strategy. Even worse is when they insist that they don’t need one, or call no distribution strategy a ‘viral marketing strategy’ … a16z is a sucker for people who have sales and marketing figured out.”

Marc Andreessen believes that a major problem with the 1999-200 bubble was that too many companies were driven by sales and marketing people who forgot or failed to appreciate that the business needed to have the ability to continually innovate. Having said that, these sales, marketing and distribution activities are essential to company success. Finding the right balance between is what great CEOs do well.

Just hoping that an offering will go viral is not going to lead a company to success since something going viral is rarely an accident. Acquiring customers cost effectively is the essence of business. Almost always the best way to acquire customers cost effectively is with an organic customer acquisition strategy. In contrast, formulating a strategy based on buying advertising is unlikely to be successful. My previous post on marketing, distribution and sales goes into detail on this point.

#11 “You spend most of your time actually dealing with your companies who are struggling and trying to help them. Because it’s the companies that are struggling or failing that actually need the most help. The companies that are succeeding are generally doing just fine without you. The companies that are failing are really the ones that need help and support. And so a lot of what you end up doing at the job is supporting struggling entrepreneurs. It’s kind of continuously humbling. You are a trouble shooter. There’s always something going wrong. Psychologically — we talk about this with our partners–you have to be psychologically prepared for the opposite. It seems like it’s going to be a life of glamor and excitement. It’s more of a life of struggle and misery. And if you are okay with that–because it’s part of the package — then the overall deal is pretty good.”

Bill Gurley likes to say that venture capital “is a service business”. Venture capital isn’t sitting in expensive chairs “picking winners” and speaking at conferences, but rather day in and day out work in the trenches helping entrepreneurs succeed.

An effective VC spends time on things like trying to recruit engineers for portfolio companies. This is not glamorous work for a venture capitalist, but it is essential work.

#12 “Software is eating the world.” “Everybody’s going to have a computer. Everybody’s going to be on the Internet. And that’s a new world. That’s a world that we’ve never lived in before. We have no idea what that world is going to look like. It’s brand new. One of the things that you know is that all of a sudden, if you can conceive of a way to make a product or a service, and if you can conceive of a way to deliver it, through software, you can now actually do that.”

“When you apply software you can do it in a very cost effective way… we now for the first time can basically go field by field, category by category, industry by industry, product by product, and we can say, ‘what would they be like if they were all software.’”

The ‘software is eating the world’ thesis has always reminded me of what Bill Gates has said about why he refused to build hardware when Paul Allen suggested they should do so in the July 1994 issue of Playboy magazine: “When you have the microprocessor doubling in power every two years, in a sense you can think of computer power as almost free. So you ask, Why be in the business of making something that’s almost free? What is the scarce resource? What is it that limits being able to get value out of that infinite computing power? Software.”

What is new today, and what Marc is talking about when he says ‘software is eating world’, is that the hardware is already in place waiting for the software at global scale. There is no longer a requirement that a software company manufacture the hardware systems needed to implement that system. Smartphones are increasingly ubiquitous. Computers and storage can be bought on demand as needed. The power of software to enable change drives Marc’s infectious optimism:

“This is sort of where I disagree so much with people who are worried about innovation slowing down, which is that I think the opposite is happening. I think innovation is accelerating. Because the minute you can take something that was not software and make it software, you can change it much faster in the future. It’s much easier to change software than it is to change something with a big, physical, real-world footprint.”

Importantly, when this innovation-driven change happens people’s lives get better. That this improvement in people’s lives is not captured in statistics like GDP, because it is consumer surplus or hard to measure, is a problem with economics — not technology or business.

Posted here by permission of the author (who blogs at 25iq.com). About the author: Tren Griffin’s professional background has primarily involved areas where business meets technologies like software and mobile communications. He currently works at Microsoft. Previously, he was a partner at private equity firm Eagle River (established by Craig McCaw) and before that, a consultant in Asia. Griffin’s latest book, Charlie Munger: The Complete Investor is about the legendary Berkshire Hathaway vice chairman, and how he invokes a set of interdisciplinary “mental models” involving economics, business, psychology, ethics, and management to keep emotions out of his investments and avoid the common pitfalls of bad judgment.

Each set of quotations is a mashup from sources like the links identified below. My transcription of video interviews may not be perfect and the text is sometimes edited to reflect the brevity required in a blog format.

sources:

- Youtube: Marc Andreessen on Big Breakthrough Ideas and Courageous Entrepreneurs

- EconTalk: Marc Andreessen on Venture Capital and the Digital Future

- Stanford’s Entrepreneurship Corner: Marc Andreessen, Serial Entrepreneur

- News Genius: Marc Andreessen on Why Software Is Eating The World

- PandoDaily: Full interview with a16z’s Marc Andreessen