From emoji and selfies-as-stickers to filters and the “Instagrammification of everything”, there’s a new era of social self-expression happening — enabled by always-accessible cameras on smartphones, now too on sunglasses; real-time computer vision/ A.I.; social media; and other tech. Several of these phenomena emerged or were popularized in Asian messaging apps before they made their way into global products. It’s very possible that China’s latest trend in mobile self-expression and entertainment, livestreaming, is next.

Livestreaming has been around in the U.S. for years but hasn’t really taken off at mainstream scale yet. There are plenty of mobile apps around the world for it, from Facebook Live to Flipagram, Inke, Instagram Stories, Live.me, Meerkat, Momo, Snapchat, Twitch, Twitter Periscope, YouNow, YY, and so on. Yet as with previous new forms of mobile self-expression, it’s taking off in China in particular: For instance, roughly 46% of China’s internet population used a livestreaming app in June 2016. Huachuang Securities estimated the mobile livestreaming market opportunity to be a $1.8B industry last year, expanding to $15.9B by 2020. Credit Suisse stated in its September research report that it believes the Chinese personal livestreaming market will be $5B next year — already just $2B less than China’s movie box office total ($7B) and half the size of its mobile gaming market.

These are startling figures given that the livestreaming explosion in China really only started a year ago. When Chinese entrepreneurs saw Meerkat’s explosive growth in March 2015, they sought to create livestreaming apps of their own; since then, over 150 livestreaming apps have been launched in China. The phenomenon is still quite young, but what do we know so far about livestreaming in China — and what can we hopefully learn as it evolves both there… and here?

#1 It’s a new form of entertainment

Although the livestreaming category had been around in China and the U.S. for over a decade, some Chinese apps (such as Inke) reframed it as social livestreaming — essentially video chatrooms where strangers gather to watch and chat with a broadcaster. This new content category helped push spontaneous livestreaming as the next evolution in self-expression, beyond selfies, stickers, and filters.

Previously, livestreaming platforms in China and the U.S. were mostly known for gaming (Twitch for example is live-gamestreaming) or pre-planned live performances for singing and dancing. Inke and other social streaming apps not only shifted the focus from the webcam to the mobile camera, but from the camera on the back of the phone to the camera on the front of the phone. In other words: from outward capture — what you are seeing or where you are — to inward capture, a.k.a. your face. To understand the significance, imagine Snapchat stories without the inward capture: It would feel more like documenting news than expressing oneself.

Livestreaming in China is thus more like a video version of selfies. And the interaction — between personal broadcasters/hosts and their audiences — is the fulcrum for engagement and monetization.

#2 Interaction replaces the need for “talent”

If one thinks of livestreaming in China as the mobile-native version of television, then social livestreaming is part reality TV, part late-night talk show. But what is so entertaining about watching everyday people stream their daily lives — laying on the couch watching TV, eating meals, driving to work, or more often than not, sitting at their desks in their bedrooms? This isn’t exactly the Truman Show!

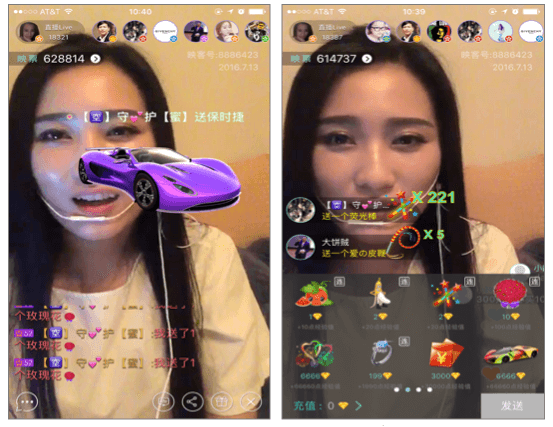

The answer lies in the interaction between broadcasters and viewers, all enabled by the platform. If a viewer likes a broadcast, he or she can send a public question, a digital gift, or multiple digital gifts to grab the broadcaster’s attention. The broadcaster can then choose to acknowledge the sender’s username and respond with a quick answer or a simple thank you. For example, let’s say you send a broadcaster a digital sticker of a sports car (a luxury sticker, usually costing over $30 apiece) and then immediately afterwards ask him or her to sing your favorite song. If the broadcaster feels up for it, he or she will thank you for the gift and honor your request — all in the public chatroom that other viewers are also watching from.

On Inke, a viewer just gifted this broadcaster a sports car sticker that cost $45 (of which the broadcaster will likely keep ~$15).

This interaction gives the sender the joy of recognition and instant gratification, gives the broadcaster financial payoffs from the digital sticker, and gives the other viewers in the room entertaining content. Viewers can thus help dictate much of the show’s “direction”.

Another gamification feature in successful livestreaming apps is the use of leaderboards to surface unknown vs. incumbent stars (which are difficult to topple on platforms like YouTube). Everything is designed around surfacing new streamers, livestreams, and trending personalities. Applied to individual broadcasters, leaderboards also highlight their top fans based on the total values of digital gifts sent. This competition among top fans for broadcasters then increases interaction and gifting.

With such a focus on viewer interaction, broadcasters rarely need to pre-plan much of their content. They just need to open the app and engage with their audience. In the past, top broadcasters had to be talented in gaming, music, dancing, or some kind of performance. Now, a top broadcaster might not have any traditional talents. In this way, putting a “social” in front of livestreaming expanded the supply of potential broadcasters in China.

#3 Digital gifting aligns incentives

Why do broadcasters choose to livestream in the first place? The reasons are simple: To feel famous, pass time, make money, and meet people.

When a viewer buys a digital gift for a broadcaster, the revenue is split between the app store, the broadcaster, and the livestreaming platform. Gifts can range anywhere between a few cents to several hundred U.S. dollars. The top broadcasters in China make tens of thousands of dollars a month — it’s not uncommon to hear stories where someone has quit his or her full time job to pursue broadcasting because it pays so much more.

Through digital gifting, broadcasters receive instant feedback that they’re loved by their fans; viewers receive acknowledgement from broadcasters they like; and platforms earn money. And because broadcasters see livestreaming as a way to make money, too, they’re incented to broadcast more frequently. As a result, China livestreaming apps have a steady supply of content — an issue that other livestreaming apps in the U.S. hadn’t overcome.

Another dynamic to note is that most of China’s social livestreaming apps focus on stranger-to-stranger networks where digital gifting as a form of communication is more culturally familiar and common. These platforms would have different gifting dynamics if the streams were from friends to existing friends.

#4 Advertising isn’t the only way to monetize

Because incentives between platform, broadcaster, and viewers are aligned through messaging and a culture of digital gifting, Chinese livestreaming platforms generate revenue right out the gate. And they do so without relying on advertising revenue or big brand campaigns.

In popular livestreaming app YY’s case, for example, advertising is a very small source of revenue: Online advertising accounted for 9.0%, 4.0%, and 1.1% of YY’s total net revenues in 2013, 2014, and 2015, respectively.

This is not to say that brands aren’t interested in the livestreaming platforms. It just means that these apps have found other ways to monetize traffic.

#5 But of course brands are experimenting with livestreaming

Global brands are already paying attention to livestreaming platforms as new channels of promoting product.

Macy’s livestreamed a tour of its Manhattan store on 34th Street, a more obvious “see what I see” livestreaming behavior. Oreo, meanwhile, took advantage of the livestreaming entertainment angle by running a campaign where a popular singer shoved Oreo cookies into his mouth while singing the list of ingredients. Xiaomi found a creative, and somewhat meta, way to use livestreaming: To show off the impressive battery life of its Mi Max phablet, it just ran a continuous stream until the battery gave out. Both stream and battery lasted 19 hours. More notably, over 39 million people watched at some point!

Other ways brands could work with livestreaming platforms/apps and broadcasters include providing branded digital gifts, which would work like product placement in traditional programming.

#6 Video is a great way to sell things, naturally!

Ecommerce companies are also adapting quickly to people’s evident demand for livestreaming. For example, Beijing-based JD.com, which ships fresh produce as JD Fresh, broadcasted a lobster-cooking competition on livestreaming app Douyu during a national holiday. Five million viewers watched the broadcast and JD Fresh saw a significant increase in its GMV during that 12-day period.

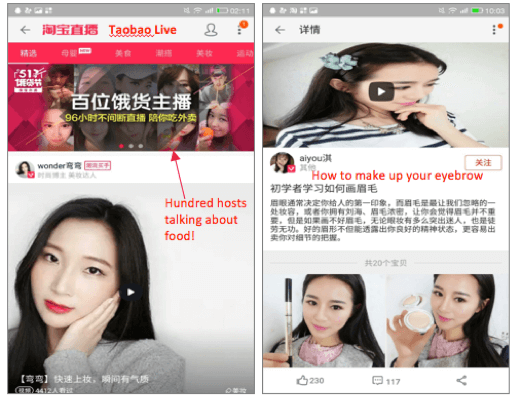

Another example is Alibaba’s Taobao (the so-called “eBay of China”), which launched a separate app, Taobao Live, where viewers can watch live broadcasts of sellers describing their merchandise. Content streamed so far includes product reviews, new product launches, and limited-time discounts. But beyond the sales they make, these broadcasters, too, can receive virtual gifts for their livestreams.

On Taobao Live, ecommerce sellers are expanding their marketing efforts through livestreaming.

Even big-name sellers are getting in on the livestreaming action: Lei Jun, the founder and CEO of Xiaomi, used their app Xiaomi Live to directly launch the Xiaomi Drone to over a million viewers.

#7 Who is livestreaming?

According to a survey of 1500 livestreaming hosts conducted by Today’s Internet Celebrity [and reported by Credit Suisse, September 2016], a little more than two-thirds are under the age of 26 and about half are at least college-educated. The most common use case for these users was chatting on the livestreaming platforms.

In general, the demographics of Chinese livestreaming app users are skewed in both gender and location.

Females make up ~80% of broadcasters, but only ~20% of the overall app users, so the audience for a majority of broadcasts is mostly male. This demographic is suited to digital gifting, since the gifts are an easy way to flirt — the digital version of “let me by you a drink”. As signals of flattery or admiration, recipients aren’t usually offended by them. And abuse prevention is managed through platform tools that allow the broadcaster and his/her top fans to permanently block misbehaving users.

It’s also worth noting that while revenue concentration hasn’t been disclosed by the platforms, some reports believe that 5% of viewers contribute 70% of virtual gift revenue. That doesn’t necessarily mean that only a small percentage of viewers send digital gifts; some of the gifters are very generous, spending thousands of dollars on these apps.

Geographically, only 11% of viewers are estimated [by Talking Data] to be in Tier 1 cities — 34% are in Tier 2 cities, and 55% live in Tier 3 cities. This suggests that for many viewers, livestreaming is a window to a world not otherwise accessible to them … and that digital gifts are a way to “buy access” to an interaction that they wouldn’t be likely to have “in real life“.

#8 From ‘internet famous’ to ‘livestream famous’

Just as YouTube surfaced a brand new category of web influencers, livestreaming is also creating a new type of celebrity. The third-party livestreaming ecosystem is still forming, but we’re already seeing the emergence of talent agencies that exclusively manage Chinese broadcasters and negotiate revenue splits with the platforms.

Many livestreaming apps are still figuring out how to produce and monetize their own professional user-generated content. For example, YY created an 18-member pop girl band called 1931 based on auditions from 40,000 contestants in China a couple years ago.

And finally, some livestreaming celebrities have tried to make the jump from amateur talent to broadcast television or movies — but not many have succeeded. One possible reason for this is that the image resolution for movies and television is much higher than that of mobile phones, and many of these web celebrities don’t look the same on the big screen!

#9 Livestreaming gives rise to (or is enabled by) a new set of beautification tools

Besides obvious factors like connectivity, bandwidth, and smartphone penetration, another technology enabling livestreaming is a new set of tools that make it easier for livestreamers to look and sound good — automatically.

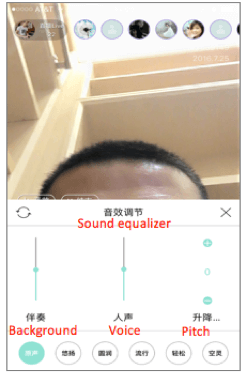

Don’t have time to do make up? No problem — there’s an app for that! (Many apps, in fact). Various livestreaming providers in China have built such broadcaster tools into their platforms; Inke, for example, has a built-in “beautycam” feature that automatically smooths skin and makes all types of blemishes disappear. (Since we’re extending the metaphor of livestreaming-as-video selfies here, it’s worth noting that there are numerous Chinese makeup and beautification apps that do this for selfies as well).

Meanwhile, for audio quality, Inke also offers a sound equalizer where the broadcaster can tune his or her voice and pitch.

These tools encourage broadcasters to stream often without much planning, ultimately increasing the amount of available content to end users and continually lowering the barriers to entry for “non-produced” (vs. established celebrity) broadcasters. It remains to be seen which group of broadcasters will stick around for the long term, however.

#10 There’s a tension between production and lack of production

The tension between production and lack of production is an especially interesting one to watch when it comes to Chinese livestreaming apps and the evolution of its talent ecosystem.

While the tools described above enable anyone to livestream in a produced-without-being-too-produced way, many popular livestreamers have constructed more highly produced “sets” dedicated for livestreaming in their bedrooms:

When it comes to the tension between produced and non-produced, there’s some interesting inversions playing out for more established internet-famous celebrities. Popular web-video celebrity Papi Jiang apparently lost a number of fans after livestreaming a clip that the audience viewed as less funny than her usual more produced web video bits.

As for traditional celebrities, time will tell. So far a top Chinese entertainment show, “I’m a Singer” live broadcasted an episode on Inke, and 10 million users tuned in. The popular South Korean boy band Big Bang also livestreamed its concert to 8 million viewers there. There are some concerns however that livestreaming such public events could affect gifting behaviors and monetization, or trigger different regulation protocols. And coming full circle to the point I opened with, none of these concert-style livestreams are really forms of personal self-expression — it’s using the outward-facing vs. inward-facing camera.

#11 Feature or product?

An open question is whether livestreaming will succeed as a standalone product/platform or whether it will be a feature added onto other apps.

As the category began to grow in China last year, some apps decided to add livestreaming functionality to their existing offerings. One example is Momo, a social dating/flirting app for meeting strangers. Since adding livestreaming later in 2015, Momo saw it contribute $15.6M in revenue in Q1 2016 — becoming the company’s largest revenue stream within just three quarters.

But it’s not just a siloed feature; livestreaming allows users to more easily find out if someone’s profile photo was overly photo-shopped, in this way extending the social interaction to a form of social proof. Livestreaming also increased engagement in other ways; for example, recipients of digital gifts on Momo viewed them as signals of sincerity, which helps make the platform more effective at matchmaking.

#12 Vertical or standalone?

On a similar note, livestreaming in China could expand to new verticals altogether. In describing the evolution of livestreaming from 1.0 (PC showrooming) to 2.0 (game streaming) to 3.0 (the current generation – mobile entertainment streaming), Credit Suisse analysts Zoe Zhao, Evan Zhou, and Angela Zhou argue that generation 4.0 will be about vertical integration. Besides ecommerce as described above, this could include education, other knowledge/skill sharing, and news media.

While I agree that this is possible and likely, I believe mobile entertainment streaming will still remain popular. It also should monetize the best, since digital gifting in this context is a form of communication. Social livestreaming is a form of self-expression and interaction, and that gets lost in combination with other apps where the focus is more on utility or information.

Furthermore, the impact of digital gifting changes when livestreaming is applied to other verticals. Tipping a teacher or a news reporter has a very different appeal than tipping a broadcaster who is playing a game of online truth-or-dare with his or her viewers. And finally, watching social livestreaming is an activity that requires little mental effort or planning for viewers and even for broadcasters. The same can’t be said of watching a livestream of an academic lecture, for example.

#13 It’s a fragmented space

With over 150 live streaming apps in China, the market is fragmented and not yet winner-take-all. While many Chinese internet players and VCs have poured millions of dollars into this space, there aren’t signs of strong network effects where the winner will have a clear and defensible moat against competitors.

While the services do become more valuable as more users join, broadcasters are not always loyal to one app. They’ll switch if another app offers more viewers, better tools, or higher payouts. In future, it’s possible that the space will consolidate as platforms begin to fight for talent, lower their take rates from digital gift revenue for broadcasters, or invest in professional user-generated content.

Or perhaps many livestreaming apps will co-exist together — just like television, which isn’t dominated by a single TV channel. I believe more than one player will be left standing in this space.

#14 It’ll be a regulated space

As with television and online video, livestreaming in China will be a regulated space. It’s already against the law to livestream pornography or similarly inappropriate content.

China’s Ministry of Culture announced just a few months ago that it was investigating a number of livestreaming platforms for hosting content that “harms social morality”. Not surprisingly, some broadcasters tried finding workarounds, and eventually livestreaming platforms had to ban such behaviors, like seductively eating bananas.

Most livestreaming apps in China employ teams of hundreds or thousands of people to monitor content on their platforms. This includes making sure that inappropriate content is flagged and not accessible, and can even extend to flagging boring content, effectively manually curating which broadcasts are featured and easiest to discover.

As the Chinese government wraps its head around the livestreaming phenomenon, there may be new clarifications regarding internal processes for platforms and required licenses for platforms and broadcasters.

#15 Chinese companies trying to go global

Although the livestreaming phenomenon I’ve described here has to date been concentrated in China, some companies are betting that’s about to change.

YY for example, owns a large stake in Bigo Live, which is taking on the Southeast Asian market. Cheetah Mobile, which I’ve noted before is one of the more savvy companies in China at expanding to international markets, is bringing Live.me, a livestreaming app, to the United States. One advantage these companies may have is that they can take the best features already popular in China, and then localize them for the rest of the world.

And even if only a fraction of those features actually take off in the United States, China could provide a directional product roadmap for the space, as it has with other mobile-first innovation.

#16 Livestreaming may be an answer to loneliness

One of the most surprising statistics of the livestreaming trend in China is that the most active hours are between 10pm and 4am, with peak usage at midnight.

As the late Heath Ledger once said, “I think the most common cause of insomnia is simple: it’s loneliness.” Loneliness is obviously a universal and growing phenomenon, but it’s somewhat of an epidemic in China for a few reasons: Most people who were born after 1979 are “only children” due to the one-child policy. Many people who work in Tier 1 mega-cities such as Beijing and Shanghai moved there for work — they’re living far away from family, childhood friends, and college friends. And for people from lower-tier cities, livestreaming provides “access” to things previously unseen let alone experienced.

Livestreaming lets broadcasters and viewers instantly interact with others, beyond the context of dating or even making new friends. And it allows people to do so in real-time, right when they feel particularly low.

Livestreaming is basically a new form of ambient and digital intimacy. If social media is just a new tool for an old behavior (to borrow from Clay Shirky), then technologies on the social web addressed our need for connection not just information. Perhaps livestreaming addresses, for some, the need for entertainment-as-companionship. It certainly changes behavior in ways that even people who thought they’d never livestream report; as one person shared, “I used to be nervous to talk to one person, now I am talking to 1,100 people at a time. I love these people who come in my broadcast and say, ‘I’m so shy, I don’t think I’ll ever broadcast.’ I’ll stop songs and give a whole speech. Why not broadcast? It changes everything.’”

Thanks to Léo Wang for his research help this summer.

Editor: Sonal Chokshi @smc90